Sketch Comedy and the Presidency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sketch Idea Generator

Sketch Idea Generator This is a guide you can use to generate sketch ideas. Keep in mind that out of 10 ideas in comedy, maybe 1 is going to turn out great. But, using these methods you can pump out ideas very quickly and get to that 1 really great idea faster. Enjoy! Adjective/ Profession/ Location Mis/Matching This one is all about pumping out ideas quickly. Make 3 lists. First a list of adjectives. Second a list of professions. Third a list of locations. Then you just connect them in a way that makes sense or in a way that makes no sense at all. Here’s an example: Adjectives Professions Locations Loud A Barista Office Quiet B Librarian A Art Museum A Brave Actor B Truck Stop C Scared C Trash Collector Library Childish Singer Restaurant Smart Mechanic C Home Responsible Pope Grocery Store B If this were on sheet paper by hand I would just draw arrows (i suggest doing it that way). But, for the sake of keeping this digitally coherent, here are some connections I could make: A) Loud > Librarian > Art Museum B) Quiet > Actor > Grocery Store C) Scared > Mechanic > Truck Stop And so on… Then you look at your connections and you try to think of some situation that those make sense. Or you go the complete opposite and connect ones that are total rubbish to put together. For example, what if a librarian, who is forced to stay quiet in her natural environment (the library) made up for it by being loud everywhere else? Next, you would brainstorm that scenario. -

Adam Sandler: Mentor Of

ADAM SANDLER: MENTOR OF MIDDLE-CLASS MASCULINITY AND MANHOOD A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Stanislaus In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History By Kathleen Boone Chapman April 2014 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL ADAM SANDLER: MENTOR OF MASCULINITY AND FATHERHOOD by Kathleen Boone Chapman Signed Certification of Approval Page is on file with the University Library Dr. Bret E. Carroll Date Professor of History Dr. Samuel Regalado Date Professor of History Dr. Marcy Rose Chvasta Date Professor of Communications © 2014 Kathleen Boone Chapman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DEDICATION I am dedicating this work to my three dear friends: Ronda James, Candace Paulson, and Michele Sniegoski. Ronda’s encouragement and obedience to the Lord gave me what I needed to go back to school with significant health issues and so late in life. Candace, who graduated from Stanford “back in the olden days,” to quote our kids, inspired me to follow my dream and become all God wants me to be. Michele’s long struggle with terminal kidney disease motivated me to keep living in spite of my own health issues. We have laughed and cried together over many years, but all of you have given me strength to carry on. Sorry two of you made it to heaven before I could get this finished. I also want to give credit to my husband of forty years who has been a faithful breadwinner, proof-reader, and a paragon of patience. What more could any woman ask for? He has also put up with me yelling at my computer and cursing Bill Gates – A LOT. -

Sam Urdank, Resume JULY

SAM URDANK Photographer 310- 877- 8319 www.samurdank.com BAD WORDS DIRECTOR: Jason Bateman CAST: Jason Bateman, Kathryn Hahn, Rohan Chand, Philip Baker Hall INDEPENDENT FILM Allison Janney, Ben Falcone, Steve Witting COFFEE TOWN DIRECTOR: Brad Campbell INDEPENDENT FILM CAST: Glenn Howerton, Steve Little, Ben Schwartz, Josh Groban Adrianne Palicki TAKEN 2 DIRECTOR: Olivier Megato TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (L.A. 1st Unit) CAST: Liam Neeson, Maggie Grace,,Famke Janssen, THE APPARITION DIRECTOR: Todd Lincoln WARNER BRO. PICTURES (L.A. 1st Unit) CAST: Ashley Greene, Sebastian Stan, Tom Felton SYMPATHY FOR DELICIOUS DIRECTOR: Mark Ruffalo CORNER STORE ENTERTAINMENT CAST: Christopher Thornton, Mark Ruffalo, Juliette Lewis, Laura Linney, Orlando Bloom, Noah Emmerich, James Karen, John Caroll Lynch EXTRACT DIRECTOR: Mike Judge MIRAMAX FILMS CAST: Jason Bateman, Mila Kunis, Kristen Wiig, Ben Affleck, JK Simmons, Clifton Curtis THE INVENTION OF LYING DIRECTOR: Ricky Gervais & Matt Robinson WARNER BROS. PICTURES CAST: Ricky Gervais, Jennifer Garner, Rob Lowe, Lewis C.K., Tina Fey, Jeffrey Tambor Jonah Hill, Jason Batemann, Philip Seymore Hoffman, Edward Norton ROLE MODELS DIRECTOR: David Wain UNIVERSAL PICTURES CAST: Seann William Scott, Paul Rudd, Jane Lynch, Christopher Mintz-Plasse Bobb’e J. Thompson, Elizabeth Banks WITLESS PROTECTION DIRECTOR: Charles Robert Carner LIONSGATE CAST: Larry the Cable Guy, Ivana Milicevic, Yaphet Kotto, Peter Stomare, Jenny McCarthy, Joe Montegna, Eric Roberts DAYS OF WRATH DIRECTOR: Celia Fox FOXY FILMS/INDEPENDENT -

'Live from New York'

Thursday, October 11, 2018 • APG News B5 5 2 0 part of the cast for _______ years. 9. He served as the original anchor for the “Weekend Update” segment of “Saturday - + ( 19. She was the first woman to host Night Live.” % “Saturday Night Live.” 11. Colin Jost and _________ currently serve as 20. “The Unfrozen Caveman __________,” was a co-anchors on the recurring “SNL” sketch # recurring character created by Jack Handey “Weekend Update.” " 5! and played by Phil Hartman on “Saturday 55 Night Live” from 1991 through 1996. 13. Actor Alec Baldwin has hosted “Saturday Night Live” more than anyone else, _________ 52 50 21. This original “SNL” cast member played a times between 1990 and 2017. 5- samurai in several sketches. 16. “Saturday TV________” was the title of a 5+ 23. Enid Strict, better known as “The recurring skit on “Saturday Night Live” 5( 5% _________Lady”, is a recurring character from featuring cartoons created by “SNL” writer aseries of sketches on “Saturday Night Live,” Robert Smigel. that was created and played by cast 5# 5" member Dana Carvey. 17. This comedian was the first to host 2! “Saturday Night Live,” in the debut October 25 24. An “SNL” episode normally begins with a 1975 episode. ________ open sketch that ends with 22 20 someone breaking character and 18. This co-creator and writer of the hit NBC 2- proclaiming, “Live from New Yo rk, it’s show “Seinfeld” briefly wrote for “SNL.” Saturday Night!” 2+ 19. This current “SNL” cast member has 2( 25. “The Boston __________” are fictional impersonated celebrities like Roseanne Barr, characters featured on “Saturday Night Live,” Meghan Trainor, Rebel Wilson and Adele. -

Ronnie Ray "Very Talented Comedian"

Ronnie Ray "Very Talented Comedian" Ronnie Ray has tremendous presence no matter what he does – Beth Lisick, The San Francisco Chronicle Originally from the south side of Chicago, Ronnie Ray’s passion in comedy transcribes into hilarious real life moments brought to the stage! Trained at The Second City Chicago Ron performs with sketch comedy ensemble Oui Be Negroes and Nation of Improv. As a stand-up comedian his material spans from a PG-13 to an R rating, with subjects that consist of growing up on the South Side of Chicago, the different types of comedians and the often requested crowd favorite that basketball star Shaquille O’Neal should retire from NBA and go back to his career as a rap artist. He his performed at a variety of clubs such as The World Famous Comedy Store (Hollywood), The Laugh Factory (Hollywood), The Improv (West Palm Beach) and Pechanga Comedy Club (Temecula) just to name a few and have been privileged to share the stage with comedy greats such as Damon Waynes, Chris Tucker and Robin Williams. His uniqueness as a comedic actor has given him the opportunity and distinction of being the only comic to perform on Playboy TV (Canoga Park and Totally Busted) AND Nickelodeon (Victorious) along with other T.V. and Movies projects. Such as Paramount Pictures “Save the Last Dance”, Groit Pictures “Redrum”, adding his voice to the Animation “Gangs of LA 1991_ and the award winning comedy from Jib Jab’s Shawshank in Minute, directed by John Landis. A gifted comedic writer, He has written numerous sketch comedy scenes of OBN and has written many spec productions with QRS Productions. -

Suddenly Mommy Program 2019

Suddenly Mommy merch available! Online at ClearlyBlonde.com Theatre INSERT NAME Presents Starring Remember The Leopard Written by Anne Marie Scheffler Print Robe from MILF Story Consultant Rosie Shuster Life Crisis? Production Design by Andy Moro Also available on www.- Original Song by Erinne White, Choreography by Nicola Pantin clearlyblonde.com Follow Anne Marie on Facebook! facebook.com/AnneMarieScheffler twitter @clearlyblonde instagram @annemariescheffler www.suddenlymommy.com Insert Date 2019 Suddenly Mommy! wrote many episodes of Square Pegs, as well as Bob and Margaret. She story edited CatDog, wrote screenplays for 6 of the major stu- Written & Performed by Anne Marie Scheffler dios including Warner Brothers and MGM. Rosie also produced many Story Consultant Rosie Shuster Carol Burnett Shows in the 90s, and a Superman's 50th Anniversary Production Design by Andy Moro Special. About Andy Moro About The Show Andy Moro has collaborated with companies including Native Earth Anne Marie Scheffler jumps into a new world of funny! Having kids! Performing Arts, Red Sky Performance, VideoCabaret, Topological Sure, she thought that’s what she always wanted, but they’re so Theatre, Cabaret Productions, Kaha:wi Dance Theatre, Buddies in much work! It looked so easy in the brochure! A mom in real life, Bad Times, Halfbreed Productions, da da kamera and more. Recent Scheffler exposes the truth of motherhood in an authentic and hilar- work includes Set and Lights for VideoCabaret’s War of 1812 at the ious way. She’ll make you feel good about your parenting skills! Stratford Festival, Set and Lights for Native Earth’s Free as Injuns, Projections for Kaha:wi’s Transmigration Set and Projections for About Anne Marie Scheffler* Kaha:wi’s Medicine Bear, Topological and YPT’s Beyond the Cuckoo’s Anne Marie is the writer and performer of 8 one woman shows, in- Nest, Waawaate Fobister’s AGOKWE and Red Sky’s Migrations at the cluding Situation: NORMA, Watch Norma’s Back, Leaving Norma, Dat- Banff Centre. -

The Creative Life of 'Saturday Night Live' Which Season Was the Most Original? and Does It Matter?

THE PAGES A sampling of the obsessive pop-culture coverage you’ll find at vulture.com ost snl viewers have no doubt THE CREATIVE LIFE OF ‘SATURDAY experienced Repetitive-Sketch Syndrome—that uncanny feeling NIGHT LIVE’ WHICH Mthat you’re watching a character or setup you’ve seen a zillion times SEASON WAS THE MOST ORIGINAL? before. As each new season unfolds, the AND DOES IT MATTER? sense of déjà vu progresses from being by john sellers 73.9% most percentage of inspired (A) original sketches season! (D) 06 (B) (G) 62.0% (F) (E) (H) (C) 01 1980–81 55.8% SEASON OF: Rocket Report, Vicki the Valley 51.9% (I) Girl. ANALYSIS: Enter 12 51.3% new producer Jean Doumanian, exit every 08 Conehead, Nerd, and 16 1975–76 sign of humor. The least- 1986–87 SEASON OF: Samurai, repetitive season ever, it SEASON OF: Church Killer Bees. ANALYSIS: taught us that if the only Lady, The Liar. Groundbreaking? breakout recurring ANALYSIS: Michaels Absolutely. Hilarious? returned in season 11, 1990–91 character is an unfunny 1982–83 Quite often. But man-child named Paulie dumped Billy Crystal SEASON OF: Wayne’s SEASON OF: Mr. Robinson’s unbridled nostalgia for Herman, you’ve got and Martin Short, and Neighborhood, The World, Hans and Franz. SNL’s debut season— problems that can only rebuilt with SNL’s ANALYSIS: Even though Whiners. ANALYSIS: Using the second-least- be fixed by, well, more broadest ensemble yet. seasons 4 and 6 as this is one of the most repetitive ever—must 32.0% Eddie Murphy. -

Top 22 Celebrities Harmed by Medical Malpractice

Center for Justice & Democracy’s TOP 22 CELEBRITIES HARMED BY MEDICAL MALPRACTICE Written by Emily Gottlieb Deputy Director for Law & Policy September 2018 Center for Justice & Democracy at New York Law School 185 West Broadway, New York, NY 10013. [email protected] ii TOP 22 CELEBRITIES HARMED BY MEDICAL MALPRACTICE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Julie Andrews .................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Marty Balin ..................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Dana Carvey .................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Glenn Frey ....................................................................................................................................... 5 5. Maurice Gibb .................................................................................................................................. 6 6. Pete Hamilton ................................................................................................................................. 7 7. Hulk Hogan ..................................................................................................................................... 7 8. Michael Jackson -

AS YOU LIKE IT, the First Production of Our 50Th Anniversary Season, and the First Show in Our Shakespearean Act

Welcome It is my pleasure to welcome you to AS YOU LIKE IT, the first production of our 50th anniversary season, and the first show in our Shakespearean act. Shakespeare’s plays have been a cornerstone of our work at CSC, and his writing continues to reflect and refract our triumphs and trials as individuals and collectively as a society. We inevitability turn to Shakespeare to express our despair, bewilderment, and delight. So, what better place to start our anniversary year than with the contemplative search for self and belonging in As You Like It. At the heart of this beautiful play is a speech that so perfectly encapsulates our mortality. All the world’s a stage, and we go through so many changes as we make our exits and our entrances. You will have noticed many changes for CSC. We have a new look, new membership opportunities, and are programming in a new way with more productions and a season that splits into what we have called “acts.” Each act focuses either on a playwright or on an era of work. It seemed appropriate to inaugurate this with a mini-season of Shakespeare, which continues with Fiasco Theater's TWELFTH NIGHT. Then there is Act II: Americans dedicated to work by American playwrights Terrence McNally (FIRE AND AIR) and Tennessee Williams (SUMMER AND SMOKE); very little of our repertoire has focused on classics written by Americans. This act also premieres a new play by Terrence McNally, as I feel that the word classic can also encapsulate the “bigger idea” and need not always be the work of a writer from the past. -

Politics of Parody

Bryant University Bryant Digital Repository English and Cultural Studies Faculty English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles Publications and Research Winter 2012 Live From New York, It's the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody Amber Day Bryant University Ethan Thompson Texas A & M University - Corpus Christi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Day, Amber and Thompson, Ethan, "Live From New York, It's the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody" (2012). English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles. Paper 44. https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Research at Bryant Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bryant Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Live from New York, It’s the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody Amber Day Assistant Professor English and Cultural Studies Bryant University 401-952-3933 [email protected] Ethan Thompson Associate Professor Department of Communication Texas A&M University - Corpus Christi 361-876-5200 [email protected] 2 Abstract Though Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” has become one of the most iconic of fake news programs, it is remarkably unfocused on either satiric critique or parody of particular news conventions. -

Dermatologist Relishes Cameo Roles

66 Practice Trends S KIN & ALLERGY N EWS • May 2008 T HE R EST OF Y OUR L IFE Dermatologist Relishes Cameo Roles riter and film director Woody down” (1999) and in “Small Time Crooks” Allen was about to leave Dr. (2000); a magician’s volunteer in “The WKenneth L. Edelson’s derma- Curse of the Jade Scorpion” (2001); an eye tology office on Manhattan’s Upper East doctor in “Hollywood Ending” (2002); a Side in March of 1986, when he turned to hotel desk clerk in “Anything Else” (2003); Dr. Edelson and made him a promise. and a disco guest in “Melinda and Melin- “In his inimitable manner, Woody da” (2005). Along the way, he has rubbed scratched his head and said, ‘You know Dr. elbows with scores of celebrities, includ- Edelson, you’re a real funny guy,’ ” re- ing Helena Bonham Carter, Mia Farrow, called Dr. Edelson, who did not know Mr. Will Ferrell, Dustin Hoffman, Helen Allen prior to that office visit. “‘I’m going Hunt, Sean Penn, Cybill Shepherd, Peter to put you in my next film.’ I thought, Weller, and Uma Thurman. ‘Yeah, right, I’ll be in the movies!’ ” Acting “allows some stress and tension DELSON The next day, Mr. Allen’s longtime cast- release,” said Dr. Edelson, who listed Jack- L. E ing director Juliet Taylor called Dr. Edelson ie Gleason, Red Skelton, Steve Allen, Lau- to confirm that Mr. Allen’s pledge was gen- rel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, and ENNETH . K R uine and to inquire about his acting histo- the Three Stooges among his favorite D ry. -

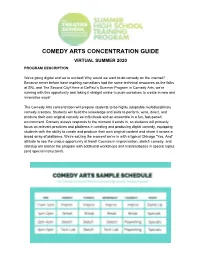

Comedy Arts Concentration Guide Virtual Summer 2020 Program Description

COMEDY ARTS CONCENTRATION GUIDE VIRTUAL SUMMER 2020 PROGRAM DESCRIPTION We’re going digital and we’re excited! Why would we want to do comedy on the internet? Because never before have aspiring comedians had the same technical resources as the folks at SNL and The Second City! Here at DePaul’s Summer Program in Comedy Arts, we’re running with this opportunity and taking it straight online to push ourselves to create in new and innovative ways! The Comedy Arts concentration will prepare students to be highly adaptable multidisciplinary comedy creators. Students will build the knowledge and skills to perform, write, direct, and produce their own original comedy as individuals and an ensemble in a fun, fast-paced environment. Comedy always responds to the moment it exists in, so students will primarily focus on relevant practices and platforms in creating and producing digital comedy, equipping students with the ability to create and produce their own original content and share it across a broad array of platforms. We’re seizing the moment we’re in with a typical Chicago “Yes, And” attitude to see the unique opportunity at hand! Courses in improvisation, sketch comedy, and standup will anchor the program with additional workshops and masterclasses in special topics (and special instructors!). SAMPLE SCHEDULE (CENTRAL DAYLIGHT TIME) Includes daily writing/digital content assignments, viewing & reading assignments. MONDAY 11:00-1:00pm Improv 1:00-2:00pm Lunch w/ optional Zoom hangouts 2:00-4:00pm Sketch Comedy 4:00-5:00pm Tech Lab TUESDAY