Intertextuality and Understanding Dave Chappelle's Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sketch Idea Generator

Sketch Idea Generator This is a guide you can use to generate sketch ideas. Keep in mind that out of 10 ideas in comedy, maybe 1 is going to turn out great. But, using these methods you can pump out ideas very quickly and get to that 1 really great idea faster. Enjoy! Adjective/ Profession/ Location Mis/Matching This one is all about pumping out ideas quickly. Make 3 lists. First a list of adjectives. Second a list of professions. Third a list of locations. Then you just connect them in a way that makes sense or in a way that makes no sense at all. Here’s an example: Adjectives Professions Locations Loud A Barista Office Quiet B Librarian A Art Museum A Brave Actor B Truck Stop C Scared C Trash Collector Library Childish Singer Restaurant Smart Mechanic C Home Responsible Pope Grocery Store B If this were on sheet paper by hand I would just draw arrows (i suggest doing it that way). But, for the sake of keeping this digitally coherent, here are some connections I could make: A) Loud > Librarian > Art Museum B) Quiet > Actor > Grocery Store C) Scared > Mechanic > Truck Stop And so on… Then you look at your connections and you try to think of some situation that those make sense. Or you go the complete opposite and connect ones that are total rubbish to put together. For example, what if a librarian, who is forced to stay quiet in her natural environment (the library) made up for it by being loud everywhere else? Next, you would brainstorm that scenario. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

Ronnie Ray "Very Talented Comedian"

Ronnie Ray "Very Talented Comedian" Ronnie Ray has tremendous presence no matter what he does – Beth Lisick, The San Francisco Chronicle Originally from the south side of Chicago, Ronnie Ray’s passion in comedy transcribes into hilarious real life moments brought to the stage! Trained at The Second City Chicago Ron performs with sketch comedy ensemble Oui Be Negroes and Nation of Improv. As a stand-up comedian his material spans from a PG-13 to an R rating, with subjects that consist of growing up on the South Side of Chicago, the different types of comedians and the often requested crowd favorite that basketball star Shaquille O’Neal should retire from NBA and go back to his career as a rap artist. He his performed at a variety of clubs such as The World Famous Comedy Store (Hollywood), The Laugh Factory (Hollywood), The Improv (West Palm Beach) and Pechanga Comedy Club (Temecula) just to name a few and have been privileged to share the stage with comedy greats such as Damon Waynes, Chris Tucker and Robin Williams. His uniqueness as a comedic actor has given him the opportunity and distinction of being the only comic to perform on Playboy TV (Canoga Park and Totally Busted) AND Nickelodeon (Victorious) along with other T.V. and Movies projects. Such as Paramount Pictures “Save the Last Dance”, Groit Pictures “Redrum”, adding his voice to the Animation “Gangs of LA 1991_ and the award winning comedy from Jib Jab’s Shawshank in Minute, directed by John Landis. A gifted comedic writer, He has written numerous sketch comedy scenes of OBN and has written many spec productions with QRS Productions. -

Discourse Types in Stand-Up Comedy Performances: an Example of Nigerian Stand-Up Comedy

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2015.3.1.filani European Journal of Humour Research 3 (1) 41–60 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Discourse types in stand-up comedy performances: an example of Nigerian stand-up comedy Ibukun Filani PhD student, Department of English, University of Ibadan [email protected] Abstract The primary focus of this paper is to apply Discourse Type theory to stand-up comedy. To achieve this, the study postulates two contexts in stand-up joking stories: context of the joke and context in the joke. The context of the joke, which is inflexible, embodies the collective beliefs of stand-up comedians and their audience, while the context in the joke, which is dynamic, is manifested by joking stories and it is made up of the joke utterance, participants in the joke and activity/situation in the joke. In any routine, the context of the joke interacts with the context in the joke and vice versa. For analytical purpose, the study derives data from the routines of male and female Nigerian stand-up comedians. The analysis reveals that stand-up comedians perform discourse types, which are specific communicative acts in the context of the joke, such as greeting/salutation, reporting and informing, which bifurcates into self- praising and self denigrating. Keywords: discourse types; stand-up comedy; contexts; jokes. 1. Introduction Humour and laughter have been described as cultural universal (Oring 2003). According to Schwarz (2010), humour represents a central aspect of everyday conversations and all humans participate in humorous speech and behaviour. This is why humour, together with its attendant effect- laughter, has been investigated in the field of linguistics and other disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, sociology and anthropology. -

Brian Regan Live! at the Bandshell Rescheduled to Thursday, June 24Th

For Immediate Release: Contact: Todd Rossi, [email protected] Brian Regan Live! At the Bandshell Rescheduled th to Thursday, June 24 (Daytona Beach, Fl- January 18, 2021) The LIVE at the Bandshell engagement with comedian BRIAN REGAN, originally scheduled for December 12, 2020 has been rescheduled to June 24, 2021. Patrons are encouraged to keep their same tickets which will be honored on the new rescheduled date. Refunds available at point of purchase. For more information or questions, please email the Peabody Auditorium at [email protected]. Critics, fans and fellow comedians agree: Brian Regan is one of the most respected comedians in the country with Vanity Fair calling Brian, "The funniest stand-up alive," and Entertainment Weekly calling him, "Your favorite comedian's favorite comedian." Having built his 30-plus year career on the strength of his material alone, Brian's non-stop theater fills the most beautiful venues across North America, visiting close to 100 cities each year. Brian starred in his own Netflix series, Stand Up And Away! With Brian Regan, which premiered on Christmas Eve 2018. Brian and Jerry Seinfeld Executive Produced the four- episode original half-hour series that combined sketch comedy and stand-up. Brian premiered his seventh hour of comedy, the Netflix special, Brian Regan: Nunchucks And Flamethrowers, in 2017, the first special in a two-special deal with Netflix, joining Brian with Dave Chappelle, Chris Rock, Jerry Seinfeld and others in multi-special deals with the channel. Brian's second Netflix special is planned for release in 2021. The Live! At the Bandshell Series features nationally known musicians and comedians performing to hundreds of socially distanced fans at the Daytona Beach Bandshell. -

(FCC) Complaints About Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020

Description of document: Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Complaints about Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020 Requested date: 2021 Release date: 21-December-2021 Posted date: 12-July-2021 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Federal Communications Commission Office of Inspector General 45 L Street NE Washington, D.C. 20554 FOIAonline The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Federal Communications Commission Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau Washington, D.C. 20554 December 21, 2021 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL FOIA Nos. -

CONSERVATIVE COMEDIAN MICHAEL LOFTUS Michael Loftus

CONSERVATIVE COMEDIAN MICHAEL LOFTUS Michael Loftus is a writer, commentator, and standup comedian, and regular guest on Fox News. He has been a headlining talent nationwide for more than twenty years, has written for The George Lopez Show and Charlie Sheen’s Anger Management, and is currently a supervising producer on Kevin Can Wait, now entering its third season. With a voice that steers center right in the political spectrum, Loftus captures in candor and humor the views of those “fly over” states. His podcast, The Loftus Party, dissects the worlds of politics, social media and pop culture, and showcases his rare ability to take complex issues, distill them into simple discussion points, and bring genuine wit and style to the proceedings. In addition to his immense writing talents, his charm and affability on stage have placed him in the upper thresholds of live performers, and he continues to be an audience favorite everywhere he goes. MAGA COUNTRY COMEDY TOUR Everyone likes to say there are no funny conservatives - as if conservatives are incapable of humor. MAGA Country Comedy, presented by The Loftus Party, is here to change all that – once and for all. With a cast of incredibly talented performers who bring years of experience to the stage – this show is undeniably funny. Chad Prather has been described as “the modern-day Will Rogers”. He is a comedian, armchair philosopher, musician, and observational humorist. His social media viral videos are measured in the hundreds of millions. He has made numerous appearances on Fox News, CNN, A&E, and The Blaze. -

Eddie Murphy in the Cut: Race, Class, Culture, and 1980S Film Comedy

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-10-2019 Eddie Murphy In The Cut: Race, Class, Culture, And 1980s Film Comedy Gail A. McFarland Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation McFarland, Gail A., "Eddie Murphy In The Cut: Race, Class, Culture, And 1980s Film Comedy." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/59 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDDIE MURPHY IN THE CUT: RACE, CLASS, CULTURE, AND 1980S FILM COMEDY by GAIL A. MCFARLAND Under the Direction of Lia T. Bascomb, PhD ABSTRACT Race, class, and politics in film comedy have been debated in the field of African American culture and aesthetics, with scholars and filmmakers arguing the merits of narrative space without adequately addressing the issue of subversive agency of aesthetic expression by black film comedians. With special attention to the 1980-1989 work of comedian Eddie Murphy, this study will look at the film and television work found in this moment as an incisive cut in traditional Hollywood industry and narrative practices in order to show black comedic agency through aesthetic and cinematic narrative subversion. Through close examination of the film, Beverly Hills Cop (Brest, 1984), this project works to shed new light on the cinematic and standup trickster influences of comedy, and the little recognized existence of the 1980s as a decade that defines a base period for chronicling and inspecting the black aesthetic narrative subversion of American film comedy. -

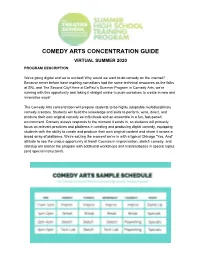

Comedy Arts Concentration Guide Virtual Summer 2020 Program Description

COMEDY ARTS CONCENTRATION GUIDE VIRTUAL SUMMER 2020 PROGRAM DESCRIPTION We’re going digital and we’re excited! Why would we want to do comedy on the internet? Because never before have aspiring comedians had the same technical resources as the folks at SNL and The Second City! Here at DePaul’s Summer Program in Comedy Arts, we’re running with this opportunity and taking it straight online to push ourselves to create in new and innovative ways! The Comedy Arts concentration will prepare students to be highly adaptable multidisciplinary comedy creators. Students will build the knowledge and skills to perform, write, direct, and produce their own original comedy as individuals and an ensemble in a fun, fast-paced environment. Comedy always responds to the moment it exists in, so students will primarily focus on relevant practices and platforms in creating and producing digital comedy, equipping students with the ability to create and produce their own original content and share it across a broad array of platforms. We’re seizing the moment we’re in with a typical Chicago “Yes, And” attitude to see the unique opportunity at hand! Courses in improvisation, sketch comedy, and standup will anchor the program with additional workshops and masterclasses in special topics (and special instructors!). SAMPLE SCHEDULE (CENTRAL DAYLIGHT TIME) Includes daily writing/digital content assignments, viewing & reading assignments. MONDAY 11:00-1:00pm Improv 1:00-2:00pm Lunch w/ optional Zoom hangouts 2:00-4:00pm Sketch Comedy 4:00-5:00pm Tech Lab TUESDAY -

FLM201 Film Genre: Understanding Types of Film (Study Guide)

Course Development Team Head of Programme : Khoo Sim Eng Course Developer(s) : Khoo Sim Eng Technical Writer : Maybel Heng, ETP © 2021 Singapore University of Social Sciences. All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Educational Technology & Production, Singapore University of Social Sciences. ISBN 978-981-47-6093-5 Educational Technology & Production Singapore University of Social Sciences 463 Clementi Road Singapore 599494 How to cite this Study Guide (MLA): Khoo, Sim Eng. FLM201 Film Genre: Understanding Types of Film (Study Guide). Singapore University of Social Sciences, 2021. Release V1.8 Build S1.0.5, T1.5.21 Table of Contents Table of Contents Course Guide 1. Welcome.................................................................................................................. CG-2 2. Course Description and Aims............................................................................ CG-3 3. Learning Outcomes.............................................................................................. CG-6 4. Learning Material................................................................................................. CG-7 5. Assessment Overview.......................................................................................... CG-8 6. Course Schedule.................................................................................................. CG-10 7. Learning Mode................................................................................................... -

Charlie Murphy / Documentary Charlie Murphy Logline Documentary

CHARLIE MURPHY / DOCUMENTARY CHARLIE MURPHY LOGLINE DOCUMENTARY 2 CHARLIE MURPHY / DOCUMENTARY CHARLIE MURPHY / DOCUMENTARY THE DOC Charlie Murphy: True Story (working title) is a feature length documentary film which tells the story of Charlie Murphy’s journey - from growing up in some of the roughest neighborhoods in Brooklyn, surpassing racial inequalities, to reaching Hollywood stardom. CHARLIE MURPHY / DOCUMENTARY LOGLINE A tribute documentary combining untold personal stories from Charlie’s family, friends and celebrity colleagues with the experience of raw uncut hilarious moments from behind the scenes never before seen footage which channel Charlie’s pain into laughter and gave birth to a new generation of Charlie’s comedic genius. CHARLIE MURPHY / DOCUMENTARY CHARLIE MURPHY / DOCUMENTARY OVERVIEW Charles Quinton Murphy grew up in Brooklyn, NY and at the age of 10 years old he endured the murder of his 27-year-old father. In the years that followed he ran with a street gang, did time in jail, served in the Navy where he faced his share of racism, sold screenplays to Hollywood, and traveled the globe as head of security for one of the most famous comedian and box office stars ever – his younger brother, Eddie Murphy. Charlie’s life changed after receiving a crucial piece of advice from a seasoned stand-up comedian in his most desperate hour; and, of course, his breakout sketches on Chappelle’s Show, which allowed Charlie the opportunity to discover that, away from the long shadow of his talented brother, Charlie, too, had the ability to make people laugh. CHARLIE MURPHY / DOCUMENTARY MY HUMOR CAME FROM ANGER. -

Nigger’ : Interpretations of the Word’S Prevalence on the Chappelle’S Show, Throughout Entertainment, and in Everyday Life

‘NIGGER’ : INTERPRETATIONS OF THE WORD’S PREVALENCE ON THE CHAPPELLE’S SHOW, THROUGHOUT ENTERTAINMENT, AND IN EVERYDAY LIFE Kyle Antar Coward A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillmen t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Dr. Anne Johnston Dr. Lucila Vargas Dr. Lois Boynton © 2007 Kyle Coward ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ‘Nigger’ : Interpretations of the Word’s Prevalence on the Chappelle’s Show , Throughout Entertainment, and in Everyday Life (Under the direction of Anne Johnston) This study analyzes the prevalence of the wor d nigger in the television sketch comedy the Chappelle’s Show – in particular, the word’s prevalence in a 2004 skit entitled “The Niggar Family” – by performing a textual reading of the five -act skit, along with conducting in -depth interviews with ten blac k individuals. In addition to the comprehension of sentiments regarding the word’s prevalence on the Chappelle’s Show , this study also analyzes how participants construct meaning out of the word as it is prevalent not only throughout entertainment in gene ral, but in everyday life outside of entertainment as well. The data from the in -depth interviews is gathered and analyzed by the utilization of the grounded theory framework of Strauss and Corbin (19 98). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS From the moment that I first began the graduate program at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication to th e present time , there were many days where I wondered if I had the resolve necessary to withstand any and all challenges that I would come to face with my studies.