The Delius Society Journal Spring 2016, Number 159

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

Pembelajaran Praktik Biola Melalui Tiga Buku Karya C

PEMBELAJARAN PRAKTIK BIOLA MELALUI TIGA BUKU KARYA C. PAUL HARFURTH, SUZUKI, DAN ABRSM PADA TINGKATAN PRADASAR DAN DASAR I DI CHANDRA KUSUMA SCHOOL: KAJIAN TERHADAP KELEBIHAN, KELEMAHAN, DAN SOLUSI TESIS Oleh SOPIAN LOREN SINAGA NIM. 117037004 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER (S2) PENCIPTAAN DAN PENGKAJIAN SENI FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2012 Universitas Sumatera Utara PEMBELAJARAN PRAKTIK BIOLA MELALUI TIGA BUKU KARYA C. PAUL HARFURTH, SUZUKI, DAN ABRSM PADA TINGKATAN PRADASAR DAN DASAR I DI CHANDRA KUSUMA SCHOOL: KAJIAN TERHADAP KELEBIHAN, KELEMAHAN, DAN SOLUSI T E S I S Untuk memperoleh gelar Magister Seni (M.Sn.) dalam Program Studi Magister (S-2) Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni pada Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Oleh SOPIAN LOREN SINAGA NIM 117037004 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER (S2) PENCIPTAAN DAN PENGKAJIAN SENI FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2013 Universitas Sumatera Utara Judul Tesis : PEMBELAJARAN PRAKTIK BIOLA MELALUI TIGA BUKU KARYA C. PAUL HARFURTH, SUZUKI, DAN ABRSM PADA TINGKATAN PRADASAR DAN DASAR I DI CHANDRA KUSUMA SCHOOL:KAJIAN TERHADAP KELEBIHAN, KELEMAHAN, DAN SOLUSI Nama : Sopian Loren Sinaga Nomor Pokok : 117037004 Program Studi : Magister (S2) Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni Menyetujui Komisi Pembimbing, Drs. Muhammad Takari, M.Hum., Ph.D. Dra. Heristina Dewi, M.Pd. NIP. 196512211991031001 NIP. 196605271994032010 Ketua Anggota Program Studi Magister (S-2) Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni Dekan, Ketua, Drs. Irwansyah Harahap, M.A. Dr. Syahron Lubis, M.A. NIP 196212211997031001 NIP 195110131976031001 Universitas Sumatera Utara Tanggal lulus: Telah diuji pada Tanggal PANITIA PENGUJI UJIAN TESIS Ketua : Drs. Irwansyah, M.A. (……………………..) Sekretaris : Drs. Torang Naiborhu, M.Hum. (..…..………………..) Anggota I : Drs. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

New on Naxos | MAY 2012

25years NEW ON The World’s Leading ClassicalNA MusicXO LabelS MAY 2012 This Month’s Other Highlights © 2012 Naxos Rights International Limited • Contact Us: [email protected] www.naxos.com • www.classicsonline.com • www.naxosmusiclibrary.com NEW ON NAXOS | MAY 2012 8.572823 Playing Time: 76:43 7 47313 28237 1 © Bruna Rausa Alessandro Marangoni Mario CASTELNUOVO-TEDESCO (1895-1968) Piano Concerto No 1 in G minor, Op 46 Piano Concerto No 2 in F major, Op 92 Four Dances from ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’, Op 167* Alessandro Marangoni, piano Malmö Symphony Orchestra • Andrew Mogrelia * First Performance and Recording Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s two Piano Concertos form a contrasting pair. Concerto No. 1, written in 1927, is a vivid and witty example of his romantic spirit, exquisite melodies and rich yet transparent orchestration. Concerto No. 2, composed a decade later, is a darker, more dramatic and virtuosic work. The deeply-felt and dreamlike slow movement and passionate finale are tinged with bleak moments of somber agitation, suggestive of unfolding tragic events with the imminent introduction of the Fascist Racial Laws that led Castelnuovo-Tedesco to seek exile in the USA in 1939. The Four Dances from ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’, part of the composer’s recurring fascination for the art of Shakespeare, are atmospheric, richly characterised and hugely enjoyable. This is their first performance and recording. After winning national and international awards, Alessandro Marangoni has appeared throughout Europe and America, as a soloist and as a © Zu Zweit chamber musician, collaborating with some of Italy’s leading performers. -

Roland Böer Orchestra E Coro Del Teatro Regio

visual cover st1819.pdf 19/10/2018 15:40:07 I CONCERTI 2018-2019 ROLAND BÖER DIRETTORE ORCHESTRA E CORO DEL TEATRO REGIO GIOVEDÌ 18 APRILE 2019 – ORE 20.30 TEATRO REGIO C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Roland Böer (foto Carlo Cofano) e l’Orchestra e il Coro del Teatro Regio (foto Edoardo Piva) Roland Böer direttore Celine Byrne soprano La vedova, Un angelo e Soprano I Marina Comparato contralto Un angelo, La regina e Contralto I Carlo Allemano tenore Obadia, Acab e Tenore I Adrian Eröd basso Elias e Basso I Maria de Lourdes Rodrigues Martins soprano Soprano II Roberta Garelli contralto Contralto II Matteo Pavlica tenore Tenore II Enrico Bava basso Basso II Valentina Escobar voce bianca Il fanciullo Andrea Secchi maestro del coro Orchestra e Coro del Teatro Regio Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847) Elias oratorio in due parti su parole dell’Antico Testamento per soli, coro e orchestra op. 70 (1845-1847) Restate in contatto con il Teatro Regio: f T Y p Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy Elias op. 70 In Germania, nella prima metà dell’Ottocento, la pratica amatoriale del canto si sviluppò anche come fattore di aggregazione sociale per una borghe- sia in piena ascesa: si moltiplicarono così Singvereine (associazioni corali) e festival musicali cittadini i cui cavalli di battaglia erano Il Messia di Händel, Le Stagioni e La Creazione di Haydn, la Nona sinfonia di Beethoven. I fe- stival promuovevano anche la composizione di nuovi oratori: una schiera di epigoni si rifece spontaneamente ai modelli della tradizione attingendo a soggetti biblici, davvero popolari nei paesi di religione protestante, dove gli ascoltatori conoscevano a memoria le Scritture. -

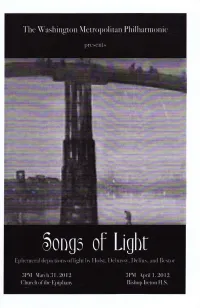

2012-0331 Program.Pdf

I\TI\OI)~I ClIO:-;~ Welcorne to Songs ofLight! JUSllikc the anists oftheir day, musicians ofthe Impressionistic CI"'J were intrigued with the cfTt.'C(S ofligtll and 50"0",11 to portray this in their music. With diminished light. the harsh cfTetts ofindustrialization were muted and these llt."\\ landst<q>cs Wert softened and made bc-Jutiful again. l1lis aftcmoon's program is filled wim ethereal depietions of light by Delius. Dehll"S)', and l-Io1st as well a~ with a sparkling new work by Charles Beslor. lei these airy musical work..<; lIallspon you to a time ofday where healilifulligiu softens the lrOublcs ofthe world bringingoullhe best ofany place. Enjo}! ,. As Illusie is lhe poetry OfSOlilld. so is paiming Ihe poclry ofsight. ~ - JUfIlt'JAblJOIf AfcNetillflllfJtler W:.ashillg'lotl Ml'tropolil.U1 rhilhanllonic. UI~"SSCS James. Music Dirt:('lOf & Condm:lor Ulys.<iCS S. James is a fonner lromhonist who studied in BOSlOll aud at Tauglcwood ..•..ith William Gibson. principal trombonist of the Bostoll Symphony On:heslra. He grddlllHcd in 1958 ....ith honurs in llIusi<: from Brown University. Mtcr a 20 yCM ~'aIttr as a surfoc-c ....~Mfare Naval Officer. followed by a second tareer as an organization and management de...e1opmem consultam. he bn-arne the music dire~1or and priocipal condtl~1or of Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic Association in 1985. The Assodation sponsors Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic. Washington ~lctropolitan YOUlh Orchestra. Washington Metropolitan Concen Orchestrd. a weekly summer chamber musie series at The Lyceum ill Old Towll Alexandria. and all anllual cOl1lpo~ition COllllletition for the Mid-Atlantic StUll'S. -

Francis Poulenc

CHAN 3134(2) CCHANHAN 33134134 WWideide bbookook ccover.inddover.indd 1 330/7/060/7/06 112:43:332:43:33 Francis Poulenc © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht The Carmelites Francis Poulenc © Stephen Vaughan © Stephen CCHANHAN 33134(2)134(2) BBook.inddook.indd 22-3-3 330/7/060/7/06 112:44:212:44:21 Francis Poulenc (1899 – 1963) The Carmelites Opera in three acts Libretto by the composer after Georges Bernanos’ play Dialogues des Carmélites, revised English version by Joseph Machlis Marquis de la Force ................................................................................ Ashley Holland baritone First Commissioner ......................................................................................James Edwards tenor Blanche de la Force, his daughter ....................................................... Catrin Wyn-Davies soprano Second Commissioner ...............................................................................Roland Wood baritone Chevalier de la Force, his son ............................................................................. Peter Wedd tenor First Offi cer ......................................................................................Toby Stafford-Allen baritone Thierry, a valet ........................................................................................... Gary Coward baritone Gaoler .................................................................................................David Stephenson baritone Off-stage voice ....................................................................................... -

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No 298662) President Lionel Carley BA, PhD Vice Presidents Roger Buckley Sir Andrew Davis CBE Sir Mark Elder CBE Bo Holten RaD Piers Lane AO, Hon DMus Martin Lee-Browne CBE David Lloyd-Jones BA, FGSM, Hon DMus Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Anthony Payne Website: delius.org.uk ISSN-0306-0373 THE DELIUS SOCIETY Chairman Position vacant Treasurer Jim Beavis 70 Aylesford Avenue, Beckenham, Kent BR3 3SD Email: [email protected] Membership Secretary Paul Chennell 19 Moriatry Close, London N7 0EF Email: [email protected] Journal Editor Katharine Richman 15 Oldcorne Hollow, Yateley GU46 6FL Tel: 01252 861841 Email: [email protected] Front and back covers: Delius’s house at Grez-sur-Loing Paintings by Ishihara Takujiro The Editor has tried in good faith to contact the holders of the copyright in all material used in this Journal (other than holders of it for material which has been specifically provided by agreement with the Editor), and to obtain their permission to reproduce it. Any breaches of copyright are unintentional and regretted. CONTENTS EDITORIAL ..........................................................................................................5 COMMITTEE NOTES..........................................................................................6 SWEDISH CONNECTIONS ...............................................................................7 DELIUS’S NORWEGIAN AND DANISH SONGS: VEHICLES OF -

Download Booklet

Benjamin James Dale (1885–1943): The Romantic Viola majesty and grandeur and a melodic sweep such as some of his original intentions in his compositions. There none other of the present generation of string- are many instances, not only in the Phantasy but also in Suite for Viola and Piano in D major, Op. 2 writers seems able to approach”. the Suite, where although he keeps a long, legato Introduction and Andante for Six Violas, Op. 5 • Phantasy for Viola and Piano, Op. 4 melody in the piano part, the viola part for a similar or Dale promoted a number of techniques that were even identical melody is broken up, with tenuto markings Edwin Evans wrote of Dale in The Musical Times on 1st October 1906. This was followed by a performance of the not often used in English chamber music at the time, to separate the legato line. I personally feel that this may May 1919: “ʻHe has written fewer and better works than complete work in 1907. Tertis, who was particularly fond such as pizzicato, tremolos, ponticello and harmonics in have been Tertisʼs suggestion, in order to give the viola any English composer of his generation.ʼ That is the of the first two movements, asked Dale to orchestrate all six parts, also instructing the sixth violaʼs C string to part a better chance of being heard alongside the considered opinion of a well-known English musician.” them. The orchestrated versions were subsequently be tuned down to a G in order to reach the bass A flat in beautiful but nevertheless somewhat thick piano writing. -

557242Bk Delius EC Sono 26/2/04 8:39 PM Page 12

557242bk Delius EC Sono 26/2/04 8:39 PM Page 12 DDD Tintner Memorial Edition Vol.10 8.557242 DELIUS Violin Concerto and other orchestral music Philippe Djokic, Violin Symphony Nova Scotia • Georg Tintner 557242bk Delius EC Sono 26/2/04 8:39 PM Page 2 TINTNER MEMORIAL EDITION • VOLUME 10 TINTNER MEMORIAL EDITION • 12 VOLUMES Frederick Delius (1862-1934) Vol.1 MOZART Symphonies Nos. 31 ‘Paris’, 35 ‘Haffner’ & 40 8.557233 Violin Concerto • Irmelin Prelude • La Calinda • The Walk to the Paradise Garden Vol. 2 SCHUBERT Symphonies Nos. 8 ‘Unfinished’ & 9 ‘The Great’ 8.557234 Intermezzo from ‘Fennimore and Gerda’ • On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring With spoken introduction by Georg Tintner Summer Night on the River • Sleigh Ride Performances recorded 5-6th December 1991 Vol. 3 BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 4 / SCHUMANN Symphony No.2 8.557235 Though Delius was born (as Fritz Theodore Albert, on amanuensis Eric Fenby in 1931. With spoken introductions by Georg Tintner 29th January 1862) in Bradford, England, of German In 1897 Delius completed his third opera, Koanga, Vol. 4 HAYDN Symphonies Nos.103 ‘Drumroll’ & 104 ‘London’ 8.557236 parents, he was the true cosmopolitan. He lived most of about Creole society in Louisiana and thus the first With spoken introduction by Georg Tintner his life in France, Scandinavia and America, and his African-American opera. The dance La Calinda, which music shows traces of them all. After a rather stern appeared in an earlier version in the Florida Suite, is Vol. 5 BRAHMS Symphony No. 3 & Serenade No. 2 8.557237 upbringing Delius was compelled to join the family one of Delius’ best-known and loveliest pieces. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op.