Wells and Wcs – SA and Finland Was Operated by Hand Pumps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FLIGHT SIMULATOR (2020) Révision 4 Microsoft (2020) AIDE-MEMOIRE 19/06/2021

FLIGHT SIMULATOR (2020) révision 4 Microsoft (2020) AIDE-MEMOIRE 19/06/2021 FLIGHT SIMULATOR (2020) Microsoft (2020) document par Asthalis [email protected] asthalis.free.fr SOMMAIRE 1. A PROPOS DE CE DOCUMENT................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 En bref.................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Versions du jeu et mises à jour............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Vocabulaire........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Conditions d'utilisation.......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. APPAREILS................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 3. AERODROMES DETAILLES.................................................................................................................................................................................... -

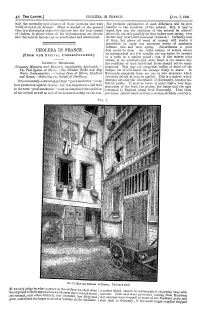

And Rouen.-Befouling the Subsoil of Drvellings. Obviously Should at Once Be Applied

48 CHOLERA IN FRANCE. half the mortality and sickness of those portions that were The probable explanation of such difference will be attri- badly or not at all drained. What is wanted at the present butable to the condition of the subsoil. But, it may be time is a thoroughly exhaustive inquiry into the local spread urged, how can the condition of the subsoil be altered ? of cholera, in places where all the circumstances are known Above all, can this possibly be done before next spring, when and the various factors can be ascertained and determined. cholera may return with increased virulence ? Certainly wa,nt of time, but above all want of money, will render it impossible to carry out extensive works of sanitation between this and next spring. Nevertheless a great CHOLERA IN FRANCE. deal could be done. An entire system of sewers cannot be in a few months, nor can water be brought (FROM OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT.) extemporised to a town in a similar period ; but, if the streets must remain in an unsatisfactory state, there is no reason why DOMESTIC DRAINAGE. the condition of each individual house should not be vastly Necessary Measures and Measures immediately Applicable.- improved. This may not altogether suffice to ward off the ?7M Pail System at Havre.-The Windom Sinks and Slop danger, but it will lessen the damage likely to ensue. In TVater Contamination.-Cholera Dens at Haver, Honfleur Normandy especially there are one or two measures which and Rouen.-Befouling the Subsoil of Drvellings. obviously should at once be applied. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

Turku Museum of History Heidi Jokinen Studio 12 Supervisor: Per Fransson Program The program is divided into a two-floor-building. The entrances of the museum are on the 1st floor. The Exhibitions begin from the entrance floor with the Major International Exhibition space which is for changing exhibitions. The exhibition is in the 1930’s warehouse building, it is an open space lined with columns which makes it easy to be transformed for different kinds of exhibitions. The Main Exhibition space for the history of Turku and Finland is on two levels on the 2nd floor. The exhibition is entered through the 1st floor Major Exhibition with a staircase leading up to the 2nd floor. The space is open with just a couple of dividing walls and columns making it flexible for changes in exhibition. For instance, the Virtual Reality Experience rooms are set between the columns on the second floor for a different kind of museum experience – Turku Goes 1812 where the visitor can experience parts of the city as it was 15 years prior to the Great fire of Turku. The Museum also houses a Museum shop, a Restaurant with seating for 150 people, and an Auditorium with 180 seats on the 1st floor. Existing Buildings The existing buildings on site are used as part of the exhibition spaces as well as a part of the restaurant dining area, museum storage area and as rentable collaboration spaces for the museum and the local businesses. Landscape The site should engage the visitor in history directly upon arrival – a stone paved pathway lined with concrete information walls leads the visitor toward the entrance. -

World Bank Document

WATER AND SANITATION PROGRAM: TECHNICAL PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized Economic Assessment of Sanitation Interventions in Yunnan Province, Public Disclosure Authorized People’s Republic of China A six-country study conducted in Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Lao PDR, the Philippines and Vietnam under the Economics of Sanitation Public Disclosure Authorized Initiative (ESI) September 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized The Water and Sanitation Program is a multi-donor partnership administered by the World Bank to support poor people in obtaining affordable, safe, and sustainable access to water and sanitation services. THE WORLD BANK Water and Sanitation Program East Asia & the Pacific Regional Office Indonesia Stock Exchange Building Tower II, 13th Fl. Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav. 52-53 Jakarta 12190 Indonesia Tel: (62-21) 5299 3003 Fax: (62 21) 5299 3004 Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) reports are published to communicate the results of WSP’s work to the development community. Some sources cited may be informal documents that are not readily available. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are entirely those of the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank or its affiliated organizations, or to members of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank Group concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. -

Turku's Archipelago with 20,000 Islands

Turku Tourist Guide The four “Must See and Do’s” when visiting Turku Moomin Valley Turku Castle The Cathedral Väski Adventure Island Municipality Facts 01 Population 175 286 Area 306,4 km² Regional Center Turku More Information 02 Internet www.turku.fi www.turkutouring.fi Turku wishes visitors a warm welcome. Photo: Åbo stads Turistinformation / Turku Touring Newspapers Åbo underrättelser www.abounderrattelser.fi/au/idag.php Turku’s Archipelago Turun Sanomat www.turunsanomat.fi with 20,000 Islands Finland’s oldest city. It’s easy to tour the archipelago. Tourist Bureaus Turku was founded along the Aura River in You can easily reach any of the 20,000 islands 1229 and the Finnish name Turku means and islets located in the Turku archipelago by Turku Touring “market place.” The city is called , “The Cradle ferry or boat (large or small). You can also Auragatan 4, Turku to Finnish Culture” and today, despite its long come close to the sea by going along the +358 2 262 74 44 history, a very modern city that offers art, Archipelago Beltway, which stretches over [email protected] music, Finnish design and much more. 200 km of bridges and islands. Here you can www.turkutouring.fi stay overnight in a small friendly hotel or B & There are direct connections with SAS / Blue B. The archipelago, with its clean nature and 1 from Stockholm or you can choose any of calm pace is relaxation for the soul! the various ferry operators that have several Notes departures daily to the city. Southwest Finland is for everyone 03 - large and small! Turku is known for its beautiful and lively The southwest area of Finland is a historic Emergency 112 squares, many cozy cafés and high-class but modern area which lies directly by the Police 07187402 61 restaurants. -

A Brief History of Six Ancient Finnish Castles

1 (2) 8.1.2014 A brief history of six ancient Finnish castles The Ancient Castles stamp booklet presents the following six ancient Finnish castles, each of which has its own interesting history. Suomenlinna Construction of Viapori Castle was started in 1748 by A. Ehrensvärd. The fortress surrendered to the Russians in 1808, and when Finland became independent, it was named Suomenlinna. In the early years of independence, it served as prison camp and closed military zone. The area started to be developed for tourism in the late 1950s, and now Suomenlinna, which lies directly in front of Helsinki, has become a popular tourist destination and is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Further information: www.suomenlinna.fi/en Häme Castle Häme Castle was founded in the late 1200s and was converted into a residential castle in the 1700s. The castle served as a prison from 1837 to 1972. Restoration work began in 1953 and was completed in 1988. Today, the castle serves as a museum and hosts a variety of exhibitions and events. Further information: www.nba.fi/en/museums/hame_castle Raseborg Castle Raseborg Castle was built in the 1370s in Snappertuna. The castle, which had been used to defend Swedish trade interests, was abandoned in the 1550s and it fell into decay. Restoration work began in the late 1800s and continued until the end of the 1980s. The castle is now open to the public during the summer. Further information: www.raseborg.org/slott/eng/ Kastelholm Castle Kastelholm was originally built to defend the Åland Islands in the late 1300s. -

Streets, Seals Or Seeds As Early Manifestations of Urban Life in Turku, Finland

Streets, seals or seeds as early manifestations of urban life in Turku, Finland Liisa Seppänen In the 2000s, the studies concerning the early phases of urbanization in Finland have re-actualized after many decades. The studies have focused on Turku, which is the oldest town of the present-day Finland and has been a target for many excavations. The focus of this paper is in the beginnings of the urbanization of Turku with the questions when and why the town was founded. The questions are old and discussed in many studies since the early 20th century. In this article, these questions are reflected on the basis recent archaeo- logical findings and the circumstantial evidence from historical sources. I am presenting my interpretation about the course of events, which led to the establishment of Turku. The town was not founded on a virgin land, but it was preceded by human activities like farming and possibly gatherings of religious or commercial nature. The political circum- stances activated the planning of the town in the late 13th century, which were realized in the turn of the 13th and 14th century. It seems, that the urbanization process took several decades and probably it was not until the mid 14th century when Turku met all the bench- marks set for the medieval town. Tracing the earliest evidence red to a more appropriate place. The document is dated in Perugia on the The origins of Turku (fig. 1) have fas- 29th of January in 1229, but it does cinated Finnish historians and archa- not, however, reveal the location of eologists for more than a century. -

Guidelines on How to Implement Maas in Local Contexts

Guidelines on How to implement MaaS in local contexts ECCENTRIC ECCENTRIC This report was developed within the framework of the CIVITAS ECCENTRIC project (2016–2020). Within the project five cities – Madrid, Stockholm, Munich, Turku and Ruse – are working together to tackle mobility challenges that are faced in suburban districts and to move towards clean and silent city logistics. www.civitas.eu/eccentric Guidelines on How to implement MaaS in local contexts Co-authors: Stella Aaltonen, Milla Wiren, Aki Koponen, Helber Y. López Covaleda Case examples: Nuppu Ervasti, Nuria Blanco, Christian Grundmann, Helene Carlsson, Nikolay Simeonov, Ruth Schawohl CIVITAS ECCENTRIC deliverable no. D3.4 Layout: Laura Sarlin Cover drawing: Laura Sarlin Published: August 2020 2 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1. MaaS measures in ECCENTRIC.........................................................................5 1.2. Expert input .........................................................................................................6 2 Context 6 2.1. Prerequisites........................................................................................................8 2.2. Data governance ..............................................................................................10 2.3. Resilience ........................................................................................................12 2.4. Drivers and barriers ........................................................................................13 2.5. Evaluation of Mobility as -

Iffr Scandinavia Section

International Fellowship of Flying Rotarians IFFR Scandinavian Section Fly In to Turku, Finland from Thursday 10th until Sunday 13th of August 2017 Welcome to IFFR Scandinavian sections meeting in Turku Turku is the oldest town in Finland, founded most likely at the end of 13th century. Turku used to be the capital of Finland, it wasn’t until 1812 Helsinki took over that role. Turku sub-region is third larget urban area in Finland and Turku is an important seaport. Turku airport is an 24/7 airport with capacity for big airplanes. The airport is situated about 10km from the center of the town. Turku area is culturally old and rich, there is lot to see and experience. During your stay, we will visit some of the main attractions but many will remain to be explored. we hope you want to come back some day for more. As public transportation in Turku area is well arranged we will mainly use public buses for transportation. You will get a three-day bus ticket. This gives us flexibility, saves the environment and gives you a good opportunity-ty to better feel day to day living in Finland. Buses are clean and safe. We are also going to walk quite a lot. A beautiful river, Aurajoki (Aura å in Swedish) runs thru the town and the street banks of the river are made for walking. So be sure to take good walking shoes with you, you will also have good use of them during the guided tour in Naantali and Turku castle. While walking, please keep your eyes open for bicycles. -

A Bucket Toilet, Also Called a Honey Bucket Or Bucket Latrine, Is a Very Simple, Basic Form of a Dry Toilet Which Is Portable

Bucket toilet - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bucket_toilet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A bucket toilet, also called a honey bucket or bucket latrine, is a very simple, basic form of a dry toilet which is portable. The bucket (pail) may be situated inside a dwelling, or in a nearby small structure (an outhouse), or on a camping site or other place that lack waste disposal plumbing. These toilets used to be common in cold climates, where installing running water can be difficult, expensive, and subject to freezing-related pipe breakage.[1] The bucket toilet may carry significant health risks compared to an improved sanitation system.[2] In regions where people do not have access to improved sanitation – particularly in low-income urban areas of developing countries – a bucket toilet might sometimes be an improvement compared to pit latrines or open defecation.[3] They are often used as a temporary measure in emergencies.[4] More sophisticated versions consist of a bucket under a wooden frame supporting a toilet seat and lid, possibly lined with a plastic bag, but A plastic bucket fitted with a toilet many are simply a large bucket without a bag. Newspaper, cardboard, seat for comfort and a lid and plastic straw, sawdust or other absorbent materials are often layered into the bag for waste containment bucket toilet. 1 Applications 1.1 Developing countries 1.2 Cold climates 1.3 Emergencies 2 Usage and maintenance 2.1 Disposal or treatment and reuse of collected excreta 3 Health aspects 4 Upgrading options 4.1 Two bucket system 4.2 Composting toilets 5History 6 Examples 6.1 Ghana 6.2 Kenya 6.3 Namibia 6.4 United States 6.5 Canada 6.6 South Africa 6.7 India 1 of 7 1/3/2017 2:53 PM Bucket toilet - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bucket_toilet 7 See also 8 References Developing countries Bucket toilets are used in households[3] and even in health care facilities[5] in some developing countries where people do not have access to improved sanitation. -

Encapsulating Visions of Nationhood Finland (1911) As a Memory Box

Encapsulating Visions of Nationhood Finland (1911) as a Memory Box HANNU SALMI At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries there was a growing interest in Finland to increase tourism by making the home country known among its own citizens and by arousing international interest in travelling to the shores of the Baltic Sea. In 1911, an international fair for tourism, Die Internationale Reise- und Fremden-Verkehr Austellung, was planned to be organised in Berlin, and the initiative was taken in Finland to produce a promotional film for the exhibition. This was exceptional in the sense that no previous film advertising an entire country is known to have been produced in the history of cinema.1 The urge to apply modern technology in building an international reputation, or at least in giving a sign of existence for the international community, was deeply rooted in the upheaval of national sentiments in Finland that was still a part of the Russian empire at the time. The policy of Russification was particularly oppressive during the years 1899–1905 and 1908–1917. Finns have traditionally called these periods sortokaudet (years of oppression) and interpreted them in terms of national threat; yet, they were in 1 On Finnish travel films, see SALMI, 2002, pp. 26-29, SEDERGREN/KIPPOLA, 2009, pp. 200-236. The credit of the first film to market an entire country has often been attributed to the long documentary Finlandia (1922), produced in the newly independent country. This credit may well be given to Finland which was made eleven years earlier despite the fact that Finland was still part of the Russian empire. -

From Stockholm to Tallinn the North Between East and West Stockholm, Turku, Helsinki, Tallinn, 28/6-6/7/18

CHAIN Cultural Heritage Activities and Institutes Network From Stockholm to Tallinn the north between east and west Stockholm, Turku, Helsinki, Tallinn, 28/6-6/7/18 Henn Roode, Seascape (Pastose II, 1965 – KUMU, Tallinn) The course is part of the EU Erasmus+ teacher staff mobility programme and organised by the CHAIN foundation, Netherlands Contents Participants & Programme............................................................................................................2 Participants............................................................................................................................3 Programme............................................................................................................................4 Performance Kalevala..............................................................................................................6 Stockholm................................................................................................................................10 Birka...................................................................................................................................11 Stockholm...........................................................................................................................13 The Allah ring.......................................................................................................................14 The Vasa.............................................................................................................................15