Effect of Sanitation on Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

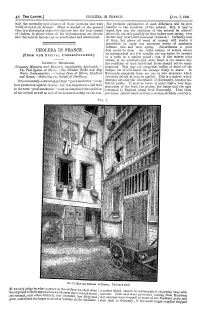

And Rouen.-Befouling the Subsoil of Drvellings. Obviously Should at Once Be Applied

48 CHOLERA IN FRANCE. half the mortality and sickness of those portions that were The probable explanation of such difference will be attri- badly or not at all drained. What is wanted at the present butable to the condition of the subsoil. But, it may be time is a thoroughly exhaustive inquiry into the local spread urged, how can the condition of the subsoil be altered ? of cholera, in places where all the circumstances are known Above all, can this possibly be done before next spring, when and the various factors can be ascertained and determined. cholera may return with increased virulence ? Certainly wa,nt of time, but above all want of money, will render it impossible to carry out extensive works of sanitation between this and next spring. Nevertheless a great CHOLERA IN FRANCE. deal could be done. An entire system of sewers cannot be in a few months, nor can water be brought (FROM OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT.) extemporised to a town in a similar period ; but, if the streets must remain in an unsatisfactory state, there is no reason why DOMESTIC DRAINAGE. the condition of each individual house should not be vastly Necessary Measures and Measures immediately Applicable.- improved. This may not altogether suffice to ward off the ?7M Pail System at Havre.-The Windom Sinks and Slop danger, but it will lessen the damage likely to ensue. In TVater Contamination.-Cholera Dens at Haver, Honfleur Normandy especially there are one or two measures which and Rouen.-Befouling the Subsoil of Drvellings. obviously should at once be applied. -

World Bank Document

WATER AND SANITATION PROGRAM: TECHNICAL PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized Economic Assessment of Sanitation Interventions in Yunnan Province, Public Disclosure Authorized People’s Republic of China A six-country study conducted in Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Lao PDR, the Philippines and Vietnam under the Economics of Sanitation Public Disclosure Authorized Initiative (ESI) September 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized The Water and Sanitation Program is a multi-donor partnership administered by the World Bank to support poor people in obtaining affordable, safe, and sustainable access to water and sanitation services. THE WORLD BANK Water and Sanitation Program East Asia & the Pacific Regional Office Indonesia Stock Exchange Building Tower II, 13th Fl. Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav. 52-53 Jakarta 12190 Indonesia Tel: (62-21) 5299 3003 Fax: (62 21) 5299 3004 Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) reports are published to communicate the results of WSP’s work to the development community. Some sources cited may be informal documents that are not readily available. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are entirely those of the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank or its affiliated organizations, or to members of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank Group concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. -

A Bucket Toilet, Also Called a Honey Bucket Or Bucket Latrine, Is a Very Simple, Basic Form of a Dry Toilet Which Is Portable

Bucket toilet - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bucket_toilet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A bucket toilet, also called a honey bucket or bucket latrine, is a very simple, basic form of a dry toilet which is portable. The bucket (pail) may be situated inside a dwelling, or in a nearby small structure (an outhouse), or on a camping site or other place that lack waste disposal plumbing. These toilets used to be common in cold climates, where installing running water can be difficult, expensive, and subject to freezing-related pipe breakage.[1] The bucket toilet may carry significant health risks compared to an improved sanitation system.[2] In regions where people do not have access to improved sanitation – particularly in low-income urban areas of developing countries – a bucket toilet might sometimes be an improvement compared to pit latrines or open defecation.[3] They are often used as a temporary measure in emergencies.[4] More sophisticated versions consist of a bucket under a wooden frame supporting a toilet seat and lid, possibly lined with a plastic bag, but A plastic bucket fitted with a toilet many are simply a large bucket without a bag. Newspaper, cardboard, seat for comfort and a lid and plastic straw, sawdust or other absorbent materials are often layered into the bag for waste containment bucket toilet. 1 Applications 1.1 Developing countries 1.2 Cold climates 1.3 Emergencies 2 Usage and maintenance 2.1 Disposal or treatment and reuse of collected excreta 3 Health aspects 4 Upgrading options 4.1 Two bucket system 4.2 Composting toilets 5History 6 Examples 6.1 Ghana 6.2 Kenya 6.3 Namibia 6.4 United States 6.5 Canada 6.6 South Africa 6.7 India 1 of 7 1/3/2017 2:53 PM Bucket toilet - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bucket_toilet 7 See also 8 References Developing countries Bucket toilets are used in households[3] and even in health care facilities[5] in some developing countries where people do not have access to improved sanitation. -

Appropriate Technology Psoa for Water Supply and Sanitation

Appropriate Technology Psoa for Water Supply and Sanitation Health Aspects of Excreta and Sullage Management-A State-of-the-Art Review Public Disclosure Authorized by Richard G. Feachem, David J. Bradley, Hemda Garelick, and D. Duncan Mara FILE COPY , Report No.:11508 Type: (PUB) Title: APPROPRIATE TECHNOLOGY FOR WAT A uthor: FEACHEM, RICHARD 4 Ext.: 0 Room: Dept.: -1-- - tOLD PUBLICATION JUNE 1931 Public Disclosure Authorized M - 5 Public Disclosure Authorized q/ Public Disclosure Authorized VWorld Bank/ A Contribution to the International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade 3 Copyright © 1980 by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank The World Bank enjoys copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, permission is hereby granted for reproduction of this material, in whole or part, for educational, scientific, or development- related purposes except those involving commercial sale provided that (a) full citation of the source is given and (b) notification in writing is given to the Director of Information and Public Affairs, the World Bank, Wqashington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. Volume 3 APPROPRIATE TECHNOLOGY FOR WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION HEALTH ASPECTS OF EXCRETA AND SULLAGE MANAGEMENT: A STATE-OF-THE-ART REVIEW The work reported herein represents the views of the authors and not necessarily those of the World Bank, nor does the Bank accept responsibility for accuracy or completeness. Transportation, Water, and Telecommunications Department The World Bank June 1981 A B S T R A C T Public Health is of central importance in the design and implementation of improved excreta disposal projects. -

The Welfare of the School Child

THE WELFARE OF THE SCHOOL CHILD JOSEPH GATES. M.D. Glass AIBMOS, Book - C 3 PRESENTED BY" ENGLISH PUBLIC HEALTH SERIES EiUed by Sir Malcolm Moious, K,C.V.0. THE WELFARE OF THE SCHOOL CHILD •7 S The Welfare of the School Child BY JOSEPH GATES M.D. State Medicine, B.S.Lond., D.P.H.Gamb. Medical Officer of Health and School Medical Officer, St. Helens ; formeriy Demonstrator of Public Health at King's College, University of Loodi>n With Six Half-tone Plates NEW YORK FUNK AND WAGNALLS COMPANY V^r'.^ mat Pnblishei' SEP a iS2Q PREFACE In these pages an attempt has been made to show the importance of healthy environment for the wel- fare of the school child. Attention is directed in various sections of the book to the need for com- prehensive and complete Public Health adminis- tration. The School Medical Service in the early stages of its growth was largely occupied in the detection and treatment of defects. The time has now come to attack the beginnings of disease and the causes of illness. Under the direction of the Ministry of Health all the forces of Preventive Medicine must be marshalled for the fray. In preparing the book, use has been made of the publications of Government Departments, and in particular the Annual Reports of the Registrar- General and of the Medical Officers of the Local Government Board and the Board of Education. To my friend Dr. Austin Nankivell I am deeply indebted for valuable criticisms and advice. J.C. ——— CONTENTS Introduction The National Importance of Healthy Childhood—Ante-natal Conditions—Effects of Parental Sickness—Venereal Disease—Maternal Inexperience—Industrial Employment of Mothers—Parental Occupation and Infant Mortality Domestic Overcrowding—Defective Sanitation—Artificial Feeding—^Need for the Reorganisation of Health Administration i CHAPTER I Malnutrition Nutrition—Causes of Malnutrition : Insufficient or Unsuit- ahle Food—Insanitary Conditions in and around the Home—^Want of Sleep—^Disease—Unsuitable Em^ploy- tnent. -

Vil1ace Regulations.______

F L ^ . i b c a ^ K PROVINCIAL GAZETTE NO. 2150 DATED 29TH JUNE. 1949 ♦ MUNICIPALITY OF JOHANNESBURG* NATIVE ______ VIL1ACE REGULATIONS.______ Aftmini3tr.nl,or*3 Notice No. ?H1. pgth June, 13.41« CHAPTER I. APPLICANTLITY AND REPEAL. 1, These regulations shall apply and have force and effect only in an area of land which has been or may hereafter be defined, set apart and laid out by the City Council of Johannesburg as a native village under paragraph (b) of sub-section (l) of section two of the Natives (Urban Areas) Consolidation Act, 1945, as amended. These regulations shall be additional to and not in substitution for any existing regulations applicable to a native village; provided that, in the event of a conflict between such existing regulations and these regulations, the provisions of thése regulations shall prevail. CERTIFICATES OF TITLE. 2. (l) Any native person over the age of 21 years who wishes to erect for his own occupation a house in a native village may apply in person to the manager of the Council'3 Non-European Affairs Department for a certificate of title to a lot in such village for that purpose. * / (2) The manager of the Council's Non-European Affairs Department * or any any official authorised by him in writing upon being satisfied that the applicant being a person possessing the qualifications set out in paragraphs (b) to (f) of this sub-regulation - (a) has submitted to him in duplicate a properly drawn plan of the proposed house, duly approved by the Council's city engineer and medical officer of health, together -

State Board of Health. 1887

/MI on 2 MARYLAND 9 C* s^^'i/* . / , >- STATE BOARD OF HEALTH. 1887. THE SANITATION OF CITIES AND TOWNS AND THE HGRICULTUm UTILIZATION OF EXCRETSL MATTERS. RBPORT ON Improved Methods of Sewage Disposal AND Water Supplies. BY C. W. CHANCELLOR, M. D., Secretary of the State Board of Health of Maryland; Member of the A merzcan Public Health Association ; Fellow of the Society of Science, Letters and Art, London, &c., &c. BALTIMORE: O.y ^ THE SUN BOOK AND JOB PKIKTING OFFICE. ^Q 18S7. ^J • >^ c MARYLAND STATE BOARD OF HEALTH. 1887. THE SHNITfiTION OF CITIES MD TOWNS .J-rr.—crvu-i O'mfi'tt.-wie-n/e) & PLEASE ACKNOWLEDGE RECEIPT. BY C. W. CHRNGELLOR, M. D.,. Secretary of the State Board of Health of Maryland; Member of the American Public Health Association ; Fellow of the Society of Science, Letters and Art, London, &c., &c. BALTIMORE: THE SUN BOOK AND JOB PKINTING OFFICE. 18S7. Entered according to Act of Cong.-csB, in the year 1837, by C. W. CIIANCELI.OR, M. D., in the Oftice of the •: ... -. ' Librarian of Congress, at Washington, U. C. , INTRODUCTORY LETTER. To His EXCELLENCY HENRY LLOYD, Governor of Maryland: DEAR SIR—In pursuance of a resolution passed by the State Board of Health on the 19tli day of November, 188G, and approved by your Excel- lency, authorizing me to proceed to Europe to investigate the most recent plans in practical operation for the disposal and utilization of household sewage, especially with reference to the sanitation of Maryland towns, and to report thereon, I herewith present the result of my labors. -

A Short Comparative History of Wells and Toilets in South Africa and Finland

Wells and WCs – SA and Finland A short comparative history of wells and toilets in South Africa and Finland * JOHANNES HAARHOFF, PETRI JUUTI AND HARRI MÄKI Abstract: This paper describes the technological development of wells and toilets and the cultural practices related to them in two countries, South Africa and Finland, from the Middle Ages to modern times. Wells and toilets have always been linked to the well-being of humans and they still are the most common technical systems in the service of mankind. They are simple to build, but if they are constructed improperly or stop functioning properly, they may endanger the health of both humans and the environment. The solutions used for getting clean water or for disposal of excrement have always been a matter of life and death for human settlements. Located on opposite sides of the world, the climate and natural resources of South Africa and Finland are very different. However, surprisingly similar solutions, for example wind turbines to pump water, have been used in rural areas. Furthermore, urbanization and industrialization occurred in both countries at approximately the same time in the 19th century, which caused increasing environmental problems in Finnish and South African urban areas. The transition to modern water supply and waste disposal systems was a very demanding process for municipal administrations in both countries. Key words: Urban environment, wells, toilets, environmental history, South Africa, Finland Although South Africa and Finland, as a result of their respective geographic localities, appear to share little in common, there are, surprisingly enough, some interesting similarities. Both are countries with climatic extremes; South Africa with its aridity and heat; and Finland with its extreme arctic conditions. -

Economic Assessment of Sanitation Interventions in Yunnan Province, People’S Republic of China

WATER AND SANITATION PROGRAM: TECHNICAL PAPER Economic Assessment of Sanitation Interventions in Yunnan Province, People’s Republic of China A six-country study conducted in Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Lao PDR, the Philippines and Vietnam under the Economics of Sanitation Initiative (ESI) September 2012 The Water and Sanitation Program is a multi-donor partnership administered by the World Bank to support poor people in obtaining affordable, safe, and sustainable access to water and sanitation services. THE WORLD BANK Water and Sanitation Program East Asia & the Pacific Regional Office Indonesia Stock Exchange Building Tower II, 13th Fl. Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav. 52-53 Jakarta 12190 Indonesia Tel: (62-21) 5299 3003 Fax: (62 21) 5299 3004 Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) reports are published to communicate the results of WSP’s work to the development community. Some sources cited may be informal documents that are not readily available. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are entirely those of the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank or its affiliated organizations, or to members of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank Group concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. Requests for permission to reproduce portions of it should be sent to [email protected]. -

The Purification of Sewage

The purification of sewage 3 1924 031 263 498 olin,anx THE PURIFICATION OF SEWAGE THE purification" OF SEWAGE BEING A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE SCIENTIFIC PRINCIPLES OF SEWAGE PURIFICATION AND THEIR PRACTICAL APPLICATION SIDNEY BARWISE, M.D.(Lond.) M.R.C.S. D.P.H.(Camb.) FELLOW OF THE SANITARY INSTITUTE MEDICAL OFFICER OF HEALTH TO THE DERBYSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL LONDON CROSBY LOCKWOOD AND SON HILL 7, STATIONERS' HALL COURT, LUDGATE 1899 PREFACE. In the present volume—a small book upon a large subject— the question of the Purification of Sewage is dealt with chiefly from a chemical and biological point of view, and in the light qf the experience gained in the discharge of my duties as the Medical Officer of Health of a large County. That office has afforded me constant opportunities for the inspec- tion of sewage works in actual operation, and for analyzing the effluents from such works. As the result, I have endeavoured to set out in these pages as succinctly as possible, and yet (it is hoped) with sufficient fulness for the purpose in view, the conditions which appear favourable for particular processes for the purification of sewage, and their necessary limitations. a3 " vi PREFACE. Until the passing of the Local Government Act, 1888, by which County Councils were constituted, the enforcement of the Eivers Pollution Prevention Act of 1876 was left in the hands of the Sanitary Authorities, who, being themselves the chief offenders against the provisions of that enactment, were, naturally enough, very loth to institute pro- ceedings against one another. -

Ecological Sanitation – a Logical Choice? the Development of the Sanitation Institution in a World Society

Tampereen teknillinen yliopisto. Julkaisu 1284 Tampere University of Technology. Publication 1284 Mia O’Neill Ecological Sanitation – A Logical Choice? The Development of the Sanitation Institution in a World Society Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to be presented with due permission for public examination and criticism in Festia Building, Auditorium Pieni sali 1, at Tampere University of Technology, on the 7th of March 2015, at 12 noon. Tampereen teknillinen yliopisto - Tampere University of Technology Tampere 2015 ISBN 978-952-15-3467-6 (printed) ISBN 978-952-15-3472-0 (PDF) ISSN 1459-2045 Author’s address Mia O’Neill Kupintie 89 33680 Tampere Finland [email protected] Supervisors Adjunct Prof. Tapio S. Katko Department of Chemistry and Bioengineering Tampere University of Technology And Dr Pekka E. Pietilä Department of Chemistry and Bioengineering Tampere University of Technology Reviewers Prof. Pertti Alasuutari Prof. Naoyuki Funamizu Adjunct Prof. Juha Kämäri Dr. Pasi Rikkonen Opponents Prof. Pertti Alasuutari Dr. Blanca Jiménez i ABSTRACT O’Neill, Mia Ecological Sanitation – A Logical Choice? The Development of the Sanitation Institution in a World Society Tampere: Tampere University of Technology, 2015 Sustainability, encompassing ecological, economic as well as socio- cultural aspects, has become a driving force for many political and administrational decisions. It is no longer enough to follow old practices or rely on profit margins – it is necessary to consider the needs of society and nature in a more holistic way as a larger whole. Sustainability is the key word also in terms of sanitation; ecological sanitation, or ecosan for short, has come to mark the sustainable approach to handling human excreta. -

Reviews/Analyses

Reviews/Analyses Effects of improved water supply and sanitation on ascariasis, diarrhoea, dracunculiasis, hookworm infection, schistosomiasis, and trachoma S.A. Esrey,' J.B. Potash,2 L. Roberts,3 & C. Shiff4 A total of 144 studies were analysed to examine the impact of improved water supply and sanitation facilities on ascariasis, diarrhoea, dracunculiasis, hookworm infection, schistosomiasis, and trachoma. These diseases were selected because they are widespread and illustrate the variety of mechanisms through which improved water and sanitation can protect people. Disease-specific median reduction levels were calculated for all studies, and separately for the more methodologically rigorous ones. For the latter studies, the median reduction in morbidity for diarrhoea, trachoma, and ascariasis induced by water supplies and/or sanitation was 26%, 27%, and 29%, respectively; the median reduction for schistoso- miasis and dracunculiasis was higher, at 77% and 78%, respectively. All studies of hookworm infection were flawed apart from one, which reported a 4% reduction in incidence. For hookworm infection, ascariasis, and schistosomiasis, the reduction in disease severity, as meas- ured in egg counts, was greater than that in incidence or prevalence. Child mortality fell by 55%, which suggests that water and sanitation have a substantial impact on child survival. Water for personal and domestic hygiene was important in reducing the rates of ascariasis, diar- rhoea, schistosomiasis, and trachoma. Sanitation facilities decreased diarrhoea