Get Another Infinite Series Which Will Contain Within It the Infinite Series of Odd Integers.” the Voice Said, “You Have the Idea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Depart..Nt at Librarllwlhlp Dectl.Ber 1974

SCIENCE FICTION I AN !NTRCIlUCTION FOR LIBRARIANS A Thes1B Presented to the Depart..nt at LibrarllWlhlp hpor1&, KaM.., state College In Partial ll'u1f'lllJlent at the Require..nte f'ar the Degrlle Muter of' L1brartlUlllhlp by Anthony Rabig . DeCtl.ber 1974 i11 PREFACE This paper is divided into five more or less independent sec tions. The first eX&lll1nes the science fiction collections of ten Chicago area public libraries. The second is a brief crttical disOUBsion of science fiction, the third section exaaines the perforaance of SClltl of the standard lib:rary selection tools in the area.of'Ulcience fiction. The fourth section oona1ats of sketches of scae of the field's II&jor writers. The appendix provides a listing of award-w1nD1ng science fio tion titles, and a selective bibli-ography of modem science fiction. The selective bibliogmphy is the author's list, renecting his OIfn 1m000ledge of the field. That 1m000ledge is not encyclopedic. The intent of this paper is to provide a brief inU'oduction and a basic selection aid in the area of science fiction for the librarian who is not faailiar With the field. None of the sections of the paper are all-inclusive. The librarian wishing to explore soience fiction in greater depth should consult the critical works of Damon Knight and J&Iles Blish, he should also begin to read science fiction magazines. TIlo papers have been Written on this subject I Elaine Thomas' A Librarian's .=.G'="=d.::.e ~ Science Fiction (1969), and Helen Galles' _The__Se_l_e_c tion 2!. Science Fiction !2!: the Public Library (1961). -

The Hilltop 8-27-1999

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University The iH lltop: 1990-2000 The iH lltop Digital Archive 8-27-1999 The iH lltop 8-27-1999 Hilltop Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_902000 Recommended Citation Staff, Hilltop, "The iH lltop 8-27-1999" (1999). The Hilltop: 1990-2000. 240. https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_902000/240 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The iH lltop Digital Archive at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH lltop: 1990-2000 by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ILLTOP The Student Voice of Howard University Since 1924 V OLUME 83, No. 3 FRIDAY, A UGUST 27, 1999 http://hilltop.howard.edu Photo 8) Eric Holl File Pho4o IIUSA \ 'ice lmldcnl Q. l~r:1h Jaclt...,11 and P,...klcnl Mnri- Dr. Janitt 'ldM>lson. head or Enrollment ~t nm\~ment 1) n Hoosen. db,t'tts.~ ~l-stml.ion "Kitka studettts. BUSA System Slow, Lines Long, Scorns Students Say By F\RAll A, 1O1,. Process S111d<·nts s.lood i11 rtw~tr.ation lines ror up to W'\l"n hours tJJ.is "t-ek. A1 tirno lines would snuke rrom tbe BL-tckbum center 10 lbunde~ Hill1op Siaff Wnter l.ibnir). l letto Uud<'nt r('\k.""~u rouM boo~ to pass the- time.. Ho1-.ird Univer ii\ Pre,1dcnt II. Patrick By CHARI FS Cou\l ,111, J11 Hilltop Staff Writer Sw) gcrt apologized lhi~ \\Cek for Ifie Uni1er,;it) ', incffo.:icncy dunng rcg.,,cr.ition ln a press release from 1hc excculht office of "It is very important for everyone A, reports of record seuing regi,u-ation tine, HUSA. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

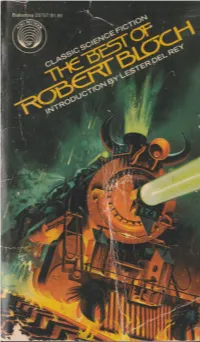

Bloch the Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett the Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L

THE STALKING DEAD The lights went out. Somebody giggled. I heard footsteps in the darkness. Mutter- ings. A hand brushed my face. Absurd, standing here in the dark with a group of tipsy fools, egged on by an obsessed Englishman. And yet there was real terror here . Jack the Ripper had prowled in dark ness like this, with a knife, a madman's brain and a madman's purpose. But Jack the Ripper was dead and dust these many years—by every human law . Hollis shrieked; there was a grisly thud. The lights went on. Everybody screamed. Sir Guy Hollis lay sprawled on the floor in the center of the room—Hollis, who had moments before told of his crack-brained belief that the Ripper still stalked the earth . The Critically Acclaimed Series of Classic Science Fiction NOW AVAILABLE: The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum Introduction by Isaac Asimov The Best of Fritz Leiber Introduction by Poul Anderson The Best of Frederik Pohl Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of Henry Kuttne'r Introduction by Ray Bradbury The Best of Cordwainer Smith Introduction by J. J. Pierce The Best of C. L. Moore Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of John W. Campbell Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of C. M. Kornbluth Introduction by Frederik Pohl The Best of Philip K. Dick Introduction by John Brunner The Best of Fredric Brown Introduction by Robert Bloch The Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett The Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L. -

The United Eras of Hip-Hop (1984-2008)

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer The United Eras of Hip-Hop tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas Examining the perception of hip-hop over the last quarter century dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx 5/1/2009 cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqLawrence Murray wertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw The United Eras of Hip-Hop ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are so many people I need to acknowledge. Dr. Kelton Edmonds was my advisor for this project and I appreciate him helping me to study hip- hop. Dr. Susan Jasko was my advisor at California University of Pennsylvania since 2005 and encouraged me to stay in the Honors Program. Dr. Drew McGukin had the initiative to bring me to the Honors Program in the first place. I wanted to acknowledge everybody in the Honors Department (Dr. Ed Chute, Dr. Erin Mountz, Mrs. Kim Orslene, and Dr. Don Lawson). Doing a Red Hot Chili Peppers project in 2008 for Mr. Max Gonano was also very important. I would be remiss if I left out the encouragement of my family and my friends, who kept assuring me things would work out when I was never certain. Hip-Hop: 2009 Page 1 The United Eras of Hip-Hop TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

Speculative Review0203.Pdf

3 speculative review SPECULATIVE REVIEW, Volume 2 Number 3, appears once more to dissect some of the current crop of science-fiction and fantasy writing. This issue represents Operation Crifanac GIXXEI. Speculative Review is a magazine of review and speculation (really, now, that’s reasonable, isn't it?) about science-fiction and fantasy. It’s published by the Washington Science- Fiction Association, and edited by Dick Eney at 4^7 Hunt Rd., Alex andria, Virginia. Speculative Review is available for letters of comment, exchanges, or — if you care to throw money — at 3 for 25^ (3 for 2/ in sterling areas.) Reason I state that so prominently is that every other person who’s written in has grotched about the absence of any informa tion about how to get future issues of SpecRev. Now you know — unless you are somebody so estimable that we’ll send you copies no matter how much you protest, or you are reviewed in here; in that case, your real problem is how to avoid having SpecRev showered on you. That is, if there are further issues of Speculative Review. With the loss of four more titles in the last few months, we’ll have to move fast to get out later numbers while there’s still science-fiction and fantasy around to be speculated about. Unless the trend begins to turn in the opposite direction we may have to take up Redd Boggs’ suggestion and turn SpedRev into a cardzine. The most depressing thing about this most recent set of deaths is the nature of the victims: Doc Lowndes, whom almost everybody in the field has always praised for his accomplishments in putting out the quality he did on the budget he had; and Hans Stefan Santesson, whom we were all getting ready to start mentioning in the same breath with the aSF-E&SF- Goldsmith Amazing trinity. -

Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, Non-Member; $1.35, Member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; V15 N1 Entire Issue October 1972

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 091 691 CS 201 266 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Science Fiction in the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Oct 72 NOTE 124p. AVAILABLE FROMKen Donelson, Ed., Arizona English Bulletin, English Dept., Ariz. State Univ., Tempe, Ariz. 85281 ($1.50); National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, non-member; $1.35, member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v15 n1 Entire Issue October 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Booklists; Class Activities; *English Instruction; *Instructional Materials; Junior High Schools; Reading Materials; *Science Fiction; Secondary Education; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Techniques IDENTIFIERS Heinlein (Robert) ABSTRACT This volume contains suggestions, reading lists, and instructional materials designed for the classroom teacher planning a unit or course on science fiction. Topics covered include "The Study of Science Fiction: Is 'Future' Worth the Time?" "Yesterday and Tomorrow: A Study of the Utopian and Dystopian Vision," "Shaping Tomorrow, Today--A Rationale for the Teaching of Science Fiction," "Personalized Playmaking: A Contribution of Television to the Classroom," "Science Fiction Selection for Jr. High," "The Possible Gods: Religion in Science Fiction," "Science Fiction for Fun and Profit," "The Sexual Politics of Robert A. Heinlein," "Short Films and Science Fiction," "Of What Use: Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "Science Fiction and Films about the Future," "Three Monthly Escapes," "The Science Fiction Film," "Sociology in Adolescent Science Fiction," "Using Old Radio Programs to Teach Science Fiction," "'What's a Heaven for ?' or; Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "A Sampler of Science Fiction for Junior High," "Popular Literature: Matrix of Science Fiction," and "Out in Third Field with Robert A. -

Broken Hopes of a Waster Youth (CD Album – Advoxya Records) - Revie

Larva – Broken Hopes Of A Waster Youth (CD Album – Advoxya Records) - revie ... Página 1 de 8 Not logged in Log-In Register • NEWS • APP • INDUSTRIAL MUSIC FORUM • TWITTER • G+ • FACEBOOK • SPOTIFY • @ Search Larva – Broken Hopes Of A Waster Youth (CD Album – Advoxya Records) Posted on 11/05/13 Industrial Music CDs at eBay USA | eBay UK | eBay DE Like Send Be the first of your friends to like this. Genre/Influences: Dark-electro. Content: The previous work I heard of Larva never totally convinced me. The dark-electronics of this Spanish formation were missing some substance and especially some cohesion. After an album released on Danse Macabre they got back to Advoxya Records releasing their 4th official album to date. This new work remains a pure dark-electro composition, which simply can be defined as ‘hell-electro’. The inspiration clearly comes from a band like Suicide Commando. The originality inside Larva is far to find, but when a band appears to be an efficient emulator of a leading name of the scene I think no one will start to complain. And that’s precisely what this album is all about. From start to finish you easily can recognize the Suicide Commando-input which appears in the dark sequences and icy melodies. Both debut songs are captivating and promising . Some calmer pieces are awakening spirits of the late 90s electro generation, but here again Larva is a quite efficient copier. The 2nd part of the album is a tiny less interesting as the songs now become quieter and more into haunting atmospheres . -

GAVIN FRIDAY Peek Aboo

edition October - December 2012 peek free of charge, not for sale 07 music quarterly published music magazine aboo magazine GAVIN FRIDAY BLANCMANGE AGENT SIDE GRINDER THE BOLLOCK BROTHERS THE BREATH OF LIFE + MIREXXX + SIMI NAH + DARK POEM + EISENFUNK + IKE YARD + JOB KARMA + METROLAND + 7JK + THE PLUTO FESTIVAL - 1 - WOOL-E-TOP 10 WOOL-E-TIPS Best Selling Releases DARK POEM (July/Aug/Sept 2012) TALES FROM THE SHADES 1. DIVE STACKS Dive Box (8CD) VOICES 2. SONAR Cut Us Up (CD) 3. VARIOUS ARTISTS Miniroboter (LP) 4. TROPIC OF CANCER Permissions Of Love (12”) 5. VARIOUS ARTISTS Something Cold (LP) 6. SSLEEPING DESIRESS Because we can’t choose not one, but two Wool-E A Voice (7”) tips!!! ‘Tales From The Shades’ is the debut CD by Ant- 7. VARIOUS ARTISTS werp-based ‘Fairyelectro’ band Dark Poem. Doomy tribal The Scrap Mag (CD) pop with heavenly voices set to a dark ambient-like under- 8. LOWER SYNTH DEPARTMENT score, with enough rough hooks to keep you wandering through their fairy wood. Beware of the Forrest Nymphs!!! Plaster Mould(LP) Our second tip also resides in Antwerp, ‘Voices’ is the 9. BONJOUR TRISTESSE debut LP of Stacks aka Sis Mathé of indie noiserockers On Not Knowing Who We Are (LP) White Circle Crime Club. Touches of John Maus, Molly 10. GAY CAT PARK Nilsson, Future Islands or even Former Ghosts come to mind. So if you like your synthpop bombastic and emo- Synthetic Woman (LP) tional, straight from the heart, then Stacks is your man or your band ;-) The Wool-E Shop - Emiel Lossystraat 17 - 9040 Ghent - Belgium VAT BE 0642.425.654 -

Fantasy & Science Fiction V025n04

p I4tk Anniversary ALL STAR ISSUE Fantasi/ and Science Fiction OCTOBER ASIMOV BESTER DAVIDSON DE CAMP HENDERSON MACLEI.SH MATHESON : Girl Of My Dreams RICHARD MATHESON 5 Epistle To Be Left In The Earth {verse) Archibald macleish 17 Books AVRAM DAVIDSON 19 Deluge {novelet) ZENNA HENDERSON 24 The Light And The Sadness {verse) JEANNETTE NICHOLS 54 Faed-out AVRAM DAVIDSON 55 How To Plan A Fauna L. SPRAGUE DE CAMP 72 Special Consent P. M. HUBBARD 84 Science; Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star ISAAC ASIMOV 90 They Don’t Make Life Like They Used To {novelet) ALFRED BESTER 100 Guest Editorial: Toward A Definition Of Science Fiction FREDRIC BROWNS' 128 In this issue . Coming next month 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by Chesley Bonestell {see page 23 for explanation) Joseph IV. Fcnnan, publisher Avram Davidson, executive editoi: Isaac Asimov, science editor Edzvard L. Forman, managing editoi; The Magasine of Fa^itasy and Science Fiction, Volume 25, No. 4, IVhole No. 149, Oct. 1963. Published monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 40c o copy. Annual subscription $4.50; $5.00 in Canada and the Pan American Union; $5.50 in all ether countries. Ptibli- cation office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N. FI. Editorial and general mail should be soit ie 347 East 53rd St., Nezv York 22, N. Y. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N. H. Printed in U. S. A. © 1963 by Mercury Press, Inc. All rights, including translations into otJut languages, reserved. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed envelopes the Publisher assumes no responsibility fur return of unsolicited manuscripts. -

Dynatron Is 915 Green Valley Road NW, Albuquerque, NM

This is the grand and have finally reached the magic ^mbe orious fanzine. we I Ah, yes, ; hundredthe issue of a not so grand and gio glorious one THE CONTENTS 3 Writings in the Sand by Roytac 6 One Prson’s View by Mike Kring Cyberpunk: 7 The Pulp Forest by Ed Cox 11 Martians, Go Figure by Dave Locke 14 En Deux Mots by Jack Speer MacCallum 17 The Old Boy’s Syndrome by Danny 0. MacCallum 20 Whither Fandom? by Paul Lagasse ARTWORK: Cover by Atom Art Hoover 2, 10, 16 My thanx to all who contributed to this issue Tackett, dDyYnNaAtTrRoOnN #100. Dynatron is 915 Green Valley Road NW, Albuquerque, NM It is, as it always has been, A Marinated Publication I and is dated December 1991 WRITINGS IN THE SAND 100 issues of DYNATRON. I am tempted to add: "That's not too many." Perhaps it is, though. Both from the point of view of the fans who have read this zine over the years and, mayhap, from the point of view of the editor/publisher. It has been a long time. You could say that in a way it is Buck Coulson's fault. My roots in the science fiction/ fantasy field go back to the 1930s. I was a reader of fantasy from the time I learned to read and read what ever children's fantasy books were Roytac when he first began available. There were not too many. to publish Dynatron. I picked up my first prozine in 1933 (which is also the time I started smoking—is there a connection?) and was instantly hooked.