How High? Tracey Ann Broussard Florida International University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CD LIST Title Save 7/9/2015 9:22:00 PM Print 7/9/2015 9:22:00 PM OPEN This on Your Computer

CD LIST Title SAve 7/9/2015 9:22:00 PM Print 7/9/2015 9:22:00 PM OPEN this on your computer. Place your cursor in the “X” Colum. Use the down arrow to move down the cell and place an “X” infront of the song you want played. Forward the file by attachment to [email protected] X TITLE ARTIST DISK TRACK Year BPM # 1 Nelly Oct01 16 #1 Nelly Top 40 #30 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams MB02 17 91 066 (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones MB08 16 65 135 (I Wanna Take) Forever Tonight Cetera, Peter MB14 15 95 106 (I’ve Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes MB11 01 87 109 (There’s Gotta Be) More To Life Staci Orrico July03 07 (This Is) Song for The Lonely Cher Jan02 6 (We’re Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley and His Comets MB07 21 55 ’03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-ZBeyonce Nov02 21 …On The Radio (Remember The Days) Nelly Furtado Feb02 8 1 Thing Amerie f./Eve May05 15 100 1,2 Step Ciara Feat. Missy Elliott Nov04 6 1,2,3,4, (Sumpin’ New) Coolio MB16 05 96 114 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou & Michie One Jan01 15 100 Years Five For Fighting Jan04 18 100% Pure Love (Radio Mix) Crystal Waters MB02 10 94 120 19-2000 Gorillaz Dec01 11 1979 Smashing Pumpkins MB18 05 1985 Bowling For Soup July04 16 21 Questions 50 Cent Rap # 6 21 Questions 50 Cent Rap 6 04 24 Jem MAR05 13 40 Kinds Of Sadness Ryan Cabrera Apr05 10 93 7 Days Craig David Nov01 5 8:15 To Nowhere Vicious Pink Retro Progressive 8th World Wonder Kimberley Lacke Jan04 12 99 Problems Jay-Z June04 7 Page 1 of 87 2 X TITLE ARTIST DISK TRACK Year BPM A Broken Living McBride, Martina A Dream El Debarge R & B #5 A Fine Romance Sax Melodies A Lifetime Better Than Ezra MAR05 7 A Little Bit Jessica Simpson Sept01 2 A Little Less Conversation Elvis Vs. -

The Hollyridge Strings

The Hollyridge Strings The Hollyridge Strings were an in-house act released by Capitol Records. Throughout the 1960's, they were perhaps best known for their instrumental versions of Beatles songs. In fact, so popular was their first album that an album exists by "The Mustangs" whose cover is a take- off of the cover to the first instrumental Beatles album by the Strings. Stu Phillips arranged and conducted the first three volumes, plus the album with solo songs on it. Perry Botkin, Jr. and Mort Garson did the honors on volume four, but Garson alone did the job on volume five. Botkin had previously conducted the Strings some years before. For the interested fanatic, here are the Hollyridge Strings' Beatles albums in all their glory: The Beatles Song Book Capitol (S)T-2116 Side One Side Two 1. From Me to You 1. Can't Buy Me Love 2. I Saw Her Standing There 2. All My Loving 3. Please Please Me 3. A Taste of Honey 4. P.S. I Love You 4. Do You Want to Know a Secret? 5. Love Me Do 5. She Loves You 6. I Want to Hold Your Hand Two songs from this LP are featured on the promotional album, Balanced for Broadcast, from June, 1964 (Capitol PRO-2634/5). The album was also reviewed in the June 6, 1964, issue of Billboard. This record surprised all critics by climbing to the #15 position in the Billboard album listings (August 22, 1964). As it continued to sell, the success of this album, the Strings' first, prompted Capitol to create a series of songbooks -- a series for which the band became known. -

Official Gazette

OFFICIAL GAZETTE EDITION GOVERNMENT PRINTIG BUREAU ENGLISH 08≫--t--#+--.fl=-1-HJB=SB!flitMBTtf EXTRA WEDNESDAY, APRIL 7, 1948 ASAKURA, Tadataka 'ASAKURA, Kan-ichi NOTICE DOTEI, Yujiro EGUCHI, Shiro ETO, Shinobu ENDO, Kiyoshi Public Notice of Screening Results No. 28 FUCHI, Kataaki FUJIMAKl', Kiohiro (March 16―March 31, 1948) FUJIMOTO, Ka:suhiko FUJITA, Yuji HAGUiMA, Kazuo HAMADA, Kazuo April 7, 1948 HANASE, Saburo HARA, Akira Director-General of Cabinet Secretariat HAYASHI Fujimaru HAYASHI, Fumiko TOMABECHI Gizo ≪, HAYASHI, Shigenori HIRAKAWA, Katamitsu 1. This table shows the screening result of the HIRAMATSU, Hideo HIRATA, Sadaichi Central Public Office Qualifications Examination HISAGANE, Akira HISATOMI, Yoshitsugu Committee, in accordance with the provisions of HISAYA, Yasuyoshi HOSHINO, Hideo Imperial Ordinance No. 1 of the same year. IEMORI, Hidetaro IGARASHI, Morishi 2. This table is to be most widely made public. IIDA, Shfro IIZUKA, Yoshihiko The office of a city, ward, town or village, shall IMAIZUMI, Kyojiro INOUE, Masao placard, upon receipt of this official report the IRI, Sadayo ISHIDA Taichiro said table. This table shall be at least placarded ISHIKAWA, Jun ITAKURA, Sadahisa for a month, and it shall, upon receipt of the ITO, Yoshitaka ITO, Yukuo next official report, be replaced by a new one. IWANAGA, "Sukegoro IWAO Akio The old report which is replaced, shall not be KABAYAMA, Hisao KAGURAI, Suzukazu destroyed, but be cound and preserved at the KAIBARA, Tsutomu KAJIYA, Mibujiro office of the city, ward, town or village, -

Research Horizons

Research Horizons Pioneering research from the University of Cambridge Issue 36 Spotlight Work Feature Mapping the galaxy Feature Obesity: the complex truth www.cam.ac.uk/research Issue 36, June 2018 2 Contents Contents News Things 4 – 5 Research news 18 – 19 “Natural history museums can save the world” Features Spotlight: Work 6 – 7 Field notes: crowdfunded to Crusoe 20 – 21 Solving the UK’s productivity puzzle 8 – 9 Turing’s wager and the mathematical mind 22 – 23 The fifty percenters 10 – 11 Muslims leaving prison talk about the layers of their lives 24 – 25 The boss of me 12 – 13 A weighty problem 26 – 27 Legislating labour in the long run 14 – 15 Galaxy quest 28 – 29 For better, for worse: how emotions shape our work life 16 – 17 The ‘brain’ that’s helping reduce carbon emissions 30 – 31 The stresses and strains of work and unemployment 3 Research Horizons Welcome 32 – 33 How do education and economic growth add up? Work shapes people’s identity and the nation’s prosperity. ‘Good’ work gives citizens security, self-worth and respect, a 34 – 35 Making the numbers count route to social mobility and, for some, the chance to turn ideas into innovations. For a country, this contributes to a healthier 36 – 37 Humans need not apply population, increasing productivity, better living standards and the development of skills that drive economic growth. Good work sounds a simple enough concept to strive towards, but the world of work is continually being buffeted by political, societal This Cambridge Life and economic forces. New technologies, demographics, free markets, gender pay gaps, zero-hours contracts, ‘gig economies’: all of these are shaping and reshaping how we work, while the labour market 38 – 39 The ‘King of Scuttle Flies’ who continues to discover continues to feel the impact of the global financial crisis and faces new species the uncertainties of Brexit. -

The Top 365 Wrestlers of 2019 Is Aj Styles the Best

THE TOP 365 WRESTLERS IS AJ STYLES THE BEST OF 2019 WRESTLER OF THE DECADE? JANUARY 2020 + + INDY INVASION BIG LEAGUES REPORT ISSUE 13 / PRINTED: 12.99$ / DIGITAL: FREE TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 Mohammad Faizan Founder & Editor in Chief _____________________________________ SENIOR WRITERS.............Nick Whitworth ..........................................Tom Yamamoto ......................................Santos Esquivel Jr SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR....…Chuck Mambo CONTRIBUTING WRITERS........Matt Taylor ..............................................Antonio Suca ..................................................7_year_ish ARTIST………………………..…ANT_CLEMS_ART PHOTOGRAPHERS………………...…MGM FOTO .........................................Pw_photo2mass ......................................art1029njpwphoto ..................................................dasion_sun ............................................Dragon000stop ............................................@morgunshow ...............................................photosneffect ...........................................jeremybelinfante Content Pg.6……………….……...….TSM 100 Pg.28.………….DECADE AWARDS Pg.29.……………..INDY INVASION Pg.32…………..THE BIG LEAGUES THE THOUGHTS EXPRESSED IN THE MAGAZINE IS OF THE EDITOR, WRITERS, WRESTLERS & ADVERTISERS. THE MAGAZINE IS NOT RELATED TO IT. ANYTHING IN THIS MAGAZINE SHOULD NOT BE REPRODUCED OR COPIED. TSM / SEPT 2019 / 2 TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 First of all I’ll like to praise the PWI for putting up a 500 list every year, I mean it’s a lot of work. Our team -

Jersey Boys Study Guide

How did four blue-collar kids become one of the greatest successes in pop music history? Have we got a story for you. Discovery Guide 1 WINNER! BEST MUSICAL ® 2006 TONY AWARD BEST MUSICAL ALBUM ® 2006 GRAMMY AWARD Directed by Des McAnuff Book by Marshall Brickman and Rick Elice Music by Bob Gaudio Lyrics by Bob Crewe Choreography by Sergio Trujillo For Jersey Boys Producers: Dodger Theatricals, Joseph J. Grano, Tamara and Kevin Kinsella, Pelican Group, in association with Latitude Link, Rick Steiner/Osher/Staton/Bell/Mayerson Group Music Direction, Vocal Arrangements & Incidental Music: Ron Melrose Scenic Design: Klara Zieglerova Costume Design: Jess Goldstein Lighting Design: Howell Binkley Sound Design: Steve Canyon Kennedy Projection Design: Michael Clark Wig and Hair Design: Charles LaPointe Fight Director: Steve Rankin Production Supervisor: Richard Hester Orchestrations: Steve Orich Music Coordinator: John Miller Technical Supervisor: Peter Fulbright East Coast Casting: Tara Rubin Casting West Coast Casting: Sharon Bialy C.S.A., Sherry Thomas C.S.A. Company Manager: Sandra Carlson Associate Producers: Lauren Mitchell, Rhoda Mayerson, Stage Entertainment Executive Producer: Sally Campbell Morse Promotions: HHC Marketing Press Representative: Boneau/Bryan Brown Jersey Boys Discovery Guide originally produced by Center Theatre Group, LA’s Theatre Company Susan Harper, Writer Rachel Fain, Managing Editor Additional Material Dodger Properties Jessica Phillips, Writer Photography Cover photo by Chris Callis All Jersey Boys production photographs ©Joan Marcus Design Maureen Rooney, Rooney Design Group Ltd Sidebar illustration©JupiterImagesCorporation 2 Introduction How did four blue-collar kids become one of the greatest successes in pop music history? Find out at the musical phenomenon, Jersey Boys. -

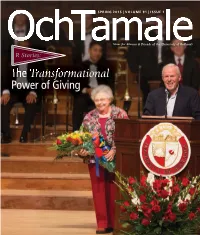

Spring 2015 | Volume 91 | Issue 1

SPRINGSPRING 2015 | VOLUME 91 | ISSUE 1 News forf Alumni & Friends of the University of Redlands R Stories: The Transformational Power of Giving Spring 2015 | 1 A BELOVED COUPLE MADE HISTORY on Saturday, October 18, 2014, with the announcement during a special event inside the Memorial Chapel that Richard “Rich” and Virginia “Ginnie” Hunsaker, both members of the Class of 1952, donated the largest single gift the University of Redlands has ever received: $35 million. This issue of Och Tamale highlights the Hunsakers’ legacy of giving and illustrates the impact of their generosity. Additional online features at OchTamaleMagazine.com Highlights of the “R Story, More photos of the “R Story, “Unbounded” musical History in the Making” History in the Making” composition (2014) 2 | Redlands.edu/OchTamalecelebration celebration Anthony Suter (b. 1979) CONTENTS 12 R Stories: The Transformational Power of Giving Richard and Virginia Hunsakers’ 50 years of giving to Redlands has transformed student lives, fostered academic excellence and nourished a culture of philanthropy. by Catherine Garcia ’06 22 Transforming Lives Through Gifts of Endowment Philanthropy takes many forms. Endowed gifts honor loved ones, support the institution and better the lives of students. by Catherine Garcia ’06 and Jennifer Dobbs ’16 24 Delivering Bulldog Athletics to the World Bulldog fans from all corners of the world tune in for live Redlands play-by-play. by Catherine Garcia ’06 Departments 2 The President’s View 3 Letters and Reflections 4 University News 8 The College 9 Graduate & Professional Programs 10 Faculty Files 11 Bulldog Athletics 26 Alumni News 31 Class Notes 37 Just Married 37 Baby Bulldogs 38 In Memoriam Back Cover Fold WILLIAM VASTA On Schedule Spring 2015 | 31 OCH TAMALE MAGAZINE VOL. -

The Quarterly Official Publication of the St

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ST. LAWRENCE COUNTY HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION GOUVERNEUR MARBLE FOR A GOUVERNEUR CHURCH The Quarterly Official Publication of The St. Lawrence County Historical Assn. CONTENTS JULY 1965 VOL 10 NO. 3 Page ASSOCIATION OFFICERS I Prcsidcrtt EDWARD F. HEIM TESTIMONIAL DINNER FOR MRS. SMITHERS 3 Canton First Vice President MILES CREENE Massem THE METHODISTS OF DEKALB JUNCTION 4 St*coad Vice Prcsidcrrt By F. F. E. Walrath MRS. EDWARD BIONbI Ogdensburg JOHN HENRY MILLS OF CANTON 5 Corresportding Sccrctary MRS. EDWARD BIONDI By G. Atwood Ma.nley OgdeMburg Financial Sccrctary MRS. W. B. FLEETHAM REMINISCENCES DePeyater By Pauline P. Nims Treancrer DAVID CLELAND Canton DEPEYSTER IN 1862 Editor, The Quortcrb By Nina W.Smithers MASON ROSSITER SMITH Couverncvr THE BAPTISTS OF GOUVERNEUR Conrrrrittec Chairrnm By Eugene Hatch Prograrrs MRS. DORIS PLANTY POST CARDS OF opdenaburg GOUVERNEUR MARBLE WORKS Historic Sites curd Afrtseurns LAWRENCE C. BOVARD Front the Lester White Collection Ogdensbm Norrrir~ations PYRITES - PAPER MILL TOWN 60 YEARS AGO CARLTON D OLDS Waddlngton By Edzvard J. Austin Yorkcr Clubs MRS. JOSEPH WRANESH UNCLE ELI AND THE GOLD RUSH Rlchvllle By Dorothy Roberts Squire Prorrtotio~ MILES GREENE M.wen. PIERREPONT BAND Couwy Fair By Mrs. Iva Tupper HAROLD STQRIE Couverneur WASHDAY IN 1898 By Mrs. William Perry THE QUARTERLY is published in January, April, July and October THE RUTLAND RAILROAD each year by the St. Lawrence Coun- By Hazel Chapman ty Historical Association, editorial, advertising and publication office 40- qz Clintm Street, Gouverneur, N.Y. WORLD HISTORY AT HEWELTON 2 I EXTRA COPIES may be obtained By Persis Yates Boyesen from Mrs. -

November 23, 2015 Wrestling Observer Newsletter

1RYHPEHU:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU1HZVOHWWHU+ROPGHIHDWV5RXVH\1LFN%RFNZLQNHOSDVVHVDZD\PRUH_:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU)LJXUH)RXU2« RADIO ARCHIVE NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE THE BOARD NEWS NOVEMBER 23, 2015 WRESTLING OBSERVER NEWSLETTER: HOLM DEFEATS ROUSEY, NICK BOCKWINKEL PASSES AWAY, MORE BY OBSERVER STAFF | [email protected] | @WONF4W TWITTER FACEBOOK GOOGLE+ Wrestling Observer Newsletter PO Box 1228, Campbell, CA 95009-1228 ISSN10839593 November 23, 2015 UFC 193 PPV POLL RESULTS Thumbs up 149 (78.0%) Thumbs down 7 (03.7%) In the middle 35 (18.3%) BEST MATCH POLL Holly Holm vs. Ronda Rousey 131 Robert Whittaker vs. Urijah Hall 26 Jake Matthews vs. Akbarh Arreola 11 WORST MATCH POLL Jared Rosholt vs. Stefan Struve 137 Based on phone calls and e-mail to the Observer as of Tuesday, 11/17. The myth of the unbeatable fighter is just that, a myth. In what will go down as the single most memorable UFC fight in history, Ronda Rousey was not only defeated, but systematically destroyed by a fighter and a coaching staff that had spent years preparing for that night. On 2/28, Holly Holm and Ronda Rousey were the two co-headliners on a show at the Staples Center in Los Angeles. The idea was that Holm, a former world boxing champion, would impressively knock out Raquel Pennington, a .500 level fighter who was known for exchanging blows and not taking her down. Rousey was there to face Cat Zingano, a fight that was supposed to be the hardest one of her career. Holm looked unimpressive, barely squeaking by in a split decision. Rousey beat Zingano with an armbar in 14 seconds. -

Hashtag Archive - #Laflood the Collected Tweets of the LA Flood Project (Esp

VIE TW STA FR END W EE RT DA YE HO MI DA YE HO MI ORD OM LANGUA MON LI T MON Y AR UR N Y AR UR N ER US GE TH MI TE TH ER T XT r Octobe 20 201 07 00 Octobe 29 201 07 00 ascend 1000 : : emo ve RTs All times are in GMT Hashtag archive - #laflood The collected tweets of the LA Flood Project (esp. April 30-May 1 demo) [ tags = laflood ] Created by @LAFloodProject on Sat Apr 30 7:11:20 GMT 2011. Contains a total of 3341 tweets. (View limited to 10000 tweets - if you want to see more - change the View Filter limit above!) Important note: The Export and Download capability for hashtags andd keywords was removed on March 20, 2011 - see here for more info View archive stats (powered by eduserv Summarizr) | | @LAFloodProject Rain has begun to fall in southern California. #laflood Thu Oct 20 07:00:04 +0000 2011 - tweet id 126915571974537216 - #1 tweet details @markcmarino RT @LAFloodProject: Rain has begun to fall in southern California. #laflood Thu Oct 20 07:02:14 +0000 2011 - tweet id 126916116969820160 - #2 tweet details @toritaylorz OMG is that rain? haha weird, i guess the weather man was right. let's see if I get to dress up in my rain gear tomorrow :) #laflood Thu Oct 20 07:02:33 +0000 2011 - tweet id 126916193092247552 - #3 tweet details @JenEmJenEm omggggg it's raining ughhhhh sunbathing plans totally ruined #laflood Thu Oct 20 07:05:35 +0000 2011 - tweet id 126916958603051009 - #4 tweet details @ZD_89 Something's going on out there. -

Issue 88.Docx

Cubed Circle Newsletter – Payback 2013 In this week’s newsletter we look at the 2013 Payback pay-per-view, as well as the fallout from RAW, the rating that the show did, NXT, a decent edition of iMPACT, All Japan fallout and SmackDown. It is a smaller issue than usual, but fear not! As next week we will be back with a look at Saturday’s New Japan Dominion show, as well as ROH’s Best in the World iPPV. We also have a few big changes coming to the newsletter in the coming months, so stay tuned for that. And with all of that out of the way, I hope that you enjoy the newsletter and have a great week. - Ryan Clingman, Cubed Circle Newsletter Editor News WWE Continue Great Run with Payback The past week and a half or so has been a great period for the WWE from a quality perspective, and they continued that run this week with a their 2013 Payback show from the Allstate Arena in Chicago. Going into the show I wasn’t expecting a blow-away card, but they over delivered with some great moments in front of a crowd that has been arguably one of their most consistently great ones over the past few years. The show was expected to be somewhat of an unnoteworthy show, but the opposite was actually the case, with multiple title changing hands, and seeds for the biggest feud of the summer, Brock Lesnar versus CM Punk, being planted during a great outing between CM Punk and Chris Jericho. -

Frankie Valli and the 4 Seasons 78 Chart Recordings in the U.S. And/Or

Frankie Valli and the 4 Seasons 78 chart recordings in the U.S. and/or Britain 61 in Billboard U.S. Hot 100 61 in the Cash Box U.S. Top 100 48 in Top 40 in the U.S. and/or Britain 24 in Top 10 in the U.S. and/or Britain 9 at No. 1 (includes Can’t Take My Eyes Off You, which reached #1 in both Cash Box and Record World and #2 in Billboard, and Let’s Hang On, which reached #1 in both Cash Box and Record World and #3 in Billboard; does not include the remix of Beggin’ reaching #1 on the British dance chart) The 4 Seasons Debut year Highest Chart Position (Billboard Hot 100 or Bubbling Under the Hot 100 except where indicated; Cash Box positions are given only if they are higher than in Billboard and Record World. Record World positions are given only if they are higher than in Cash Box and Billboard.) No. 1 records are in red. Other Top 10 records are in blue. Other Top 40 records are in green. 1. 1956 You’re the Apple of My Eye (The Four Lovers) #62 2. 1962 Sherry #1 (five weeks at No. 1 in Billboard and six weeks at No. 1 in Cash Box) 3. 1962 Big Girls Don’t Cry #1 (5 weeks) 4. 1962 Santa Claus is Coming to Town #23 5. 1963 Walk Like a Man #1 (3 weeks) 6. 1963 Peanuts #108 7. 1963 Since I Don’t Have You #123 same recording also reached #105 in 1965 8.