Fall 2000 159 the Theatre of Heiner Midler By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadway the BROAD Way”

MEDIA CONTACT: Fred Tracey Marketing/PR Director 760.643.5217 [email protected] Bets Malone Makes Cabaret Debut at ClubM at the Moonlight Amphitheatre on Jan. 13 with One-Woman Show “Broadway the BROAD Way” Download Art Here Vista, CA (January 4, 2018) – Moonlight Amphitheatre’s ClubM opens its 2018 series of cabaret concerts at its intimate indoor venue on Sat., Jan. 13 at 7:30 p.m. with Bets Malone: Broadway the BROAD Way. Making her cabaret debut, Malone will salute 14 of her favorite Broadway actresses who have been an influence on her during her musical theatre career. The audience will hear selections made famous by Fanny Brice, Carol Burnett, Betty Buckley, Carol Channing, Judy Holliday, Angela Lansbury, Patti LuPone, Mary Martin, Ethel Merman, Liza Minnelli, Bernadette Peters, Barbra Streisand, Elaine Stritch, and Nancy Walker. On making her cabaret debut: “The idea of putting together an original cabaret act where you’re standing on stage for ninety minutes straight has always sounded daunting to me,” Malone said. “I’ve had the idea for this particular cabaret format for a few years. I felt the time was right to challenge myself, and I couldn’t be more proud to debut this cabaret on the very stage that offered me my first musical theatre experience as a nine-year-old in the Moonlight’s very first musical Oliver! directed by Kathy Brombacher.” Malone can relate to the fact that the leading ladies she has chosen to celebrate are all attached to iconic comedic roles. “I learned at a very young age that getting laughs is golden,” she said. -

Exhibits Registrations

July ‘09 EXHIBITS In the Main Gallery MONDAY TUESDAY SATURDAY ART ADVISORY COUNCIL MEMBERS’ 6 14 “STREET ANGEL” (1928-101 min.). In HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free 18 SHOW, throughout the summer. AAC MANHASSET BAY BOAT TOURS: Have “laughter-loving, careless, sordid Naples,” screening by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. a look at Manhasset Bay – from the water! In the Photography Gallery a fugitive named Angela (Oscar winner to 2 p.m. A free 90-minute boat tour will explore Janet Gaynor) joins a circus and falls in Legendary Long the history and ecology of our corner of love with a vagabond painter named Gino TOPICAL TUESDAY: Islanders. What do Billy Joel, Martha Stew- Long Island Sound. Tour dates are July (Charles Farrell). Philip Klein and Henry art, Kiri Te Kanawa and astronaut Dr. Mary 18; August 8 and 29. The tour is free, but Roberts Symonds scripted, from a novel Cleave have in common? They have all you must register at the Information Desk by Monckton Hoffe, for director Frank lived on Long Island and were interviewed for the 30 available seats. Registration for Borzage. Ernest Palmer and Paul Ivano by Helene Herzig when she was feature the July 18 tour begins July 2; Registration provided the glistening cinematography. editor of North Shore Magazine. Herzig has for the August tours begins July 21. Phone Silent with orchestral score. 7:30 p.m. collected more than 70 of her interviews, registration is acceptable. Tours at 1 and written over a 20-year period. The celebri- 3 p.m. Call 883-4400, Ext. -

The Pirates of Penzance

HOT Season for Young People 2014-15 Teacher Guidebook NASHVILLE OPERA SEASON SPONSOR From our Season Sponsor For over 130 years Regions has been proud to be a part of the Middle Tennessee community, growing and thriving as our area has. From the opening of our doors on September 1, 1883, we have committed to this community and our customers. One area that we are strongly committed to is the education of our students. We are proud to support TPAC’s Humanities Outreach in Tennessee Program. What an important sponsorship this is – reaching over 25,000 students and teachers – some students would never see a performing arts production without this program. Regions continues to reinforce its commitment to the communities it serves and in addition to supporting programs such as HOT, we have close to 200 associates teaching financial literacy in classrooms this year. , for giving your students this wonderful opportunity. They will certainly enjoy Thankthe experience. you, Youteachers are creating memories of a lifetime, and Regions is proud to be able to help make this opportunity possible. ExecutiveJim Schmitz Vice President, Area Executive Middle Tennessee Area 2014-15 HOT Season for Young People CONTENTS Dear Teachers~ We are so pleased to be able Opera rehearsal information page 2 to partner with Nashville Opera to bring students to Opera 101 page 3 the invited dress rehearsal Short Explorations page 4 of The Pirates of Penzance. Cast list and We thank Nashville Opera Opera Information NOG-1 for the use of their extensive The Story NOG-2,3 study guide for adults. -

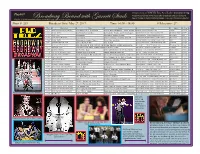

Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack

Originating on WMNR Fine Arts Radio [email protected] Playlist* Program is archived 24-48 hours after broadcast and can be heard Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack free of charge at Public Radio Exchange, > prx.org > Broadway Bound *Playlist is listed alphabetically by show (disc) title, not in order of play. Show #: 269 Broadcast Date: May 27, 2017 Time: 16:00 - 18:00 # Selections: 27 Time Writer(s) Title Artist Disc Label Year Position Comment File Number Intro Track Holiday Release Date Date Played Date Played Copy 3:24 Menken|Ashman|Rice|Beguelin Somebody's Got Your Back James Monroe Iglehart, Adam Jacobs & Aladdin Original Broadway Cast Disney 2014 Opened 3/20/2014 CDS Aladdin 15 2014 8/16/14 12/6/14 1/7/17 5/27/17 3:17 Irving Berlin Anything You Can Do Bernadette“friends” Peters and Tom Wopat Annie Get Your Gun - New Broadway Cast Broadway Angel 1999 3/4/1999 - 9/1/2001. 1045 perf. 2 Tony Awards: Best Revival. Best Actress, CDS Anni none 18 1999 6/7/08 5/27/17 Bernadette Peters. 3:30 Cole Porter Friendship Joel Grey, Sutton Foster Anything Goes - New Broadway Cast 2011 Ghostlight 2011 Opened 4/7/11 at the Stephen Sondheim Theater. THREE 2011 Tony Awards: Best Revival CDS Anything none 9 2011 12/10/113/31/12 5/27/17 of a Musical; Best Actress in a Musical: Sutton Foster; Best Choreography: Kathleen 2:50 John Kander/Fred Ebb Two Ladies Alan Cumming, Erin Hill & Michael Cabaret: The New Broadway Cast Recording RCA Victor 1998 3/19/1998 - 1/4/2004. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

James Ivory in France

James Ivory in France James Ivory is seated next to the large desk of the late Ismail Merchant in their Manhattan office overlooking 57th Street and the Hearst building. On the wall hangs a large poster of Merchant’s book Paris: Filming and Feasting in France. It is a reminder of the seven films Merchant-Ivory Productions made in France, a source of inspiration for over 50 years. ....................................................Greta Scacchi and Nick Nolte in Jefferson in Paris © Seth Rubin When did you go to Paris for the first time? Jhabvala was reading. I had always been interested in Paris in James Ivory: It was in 1950, and I was 22. I the 1920’s, and I liked the story very much. Not only was it my had taken the boat train from Victoria Station first French film, but it was also my first feature in which I in London, and then we went to Cherbourg, thought there was a true overall harmony and an artistic then on the train again. We arrived at Gare du balance within the film itself of the acting, writing, Nord. There were very tall, late 19th-century photography, décor, and music. apartment buildings which I remember to this day, lining the track, which say to every And it brought you an award? traveler: Here is Paris! JI: It was Isabelle Adjani’s first English role, and she received for this film –and the movie Possession– the Best Actress You were following some college classmates Award at the Cannes Film Festival the following year. traveling to France? JI: I did not want to be left behind. -

The Death of Donald Moffat, Legendary MOURNING Actor, Distinguished

Senate Resolution No. 503 BY: Senator HARCKHAM MOURNING the death of Donald Moffat, legendary actor, distinguished citizen and gifted artist WHEREAS, It is the sense of this Legislative Body to honor and pay just tribute to the memory of those prominent individuals whose creative talents have contributed to the entertainment and cultural enrichment of the citizens of the State of New York; and WHEREAS, Donald Moffat, a beloved actor of stage, screen and television, died on Thursday, December 20, 2018, in Sleepy Hollow, New York, at the age of 87; and WHEREAS, Born in Plymouth, England, on December 26, 1930, Donald Moffat was the only child of Kathleen Mary (Smith) and Walter George Moffat; his parents ran a boarding house in Totnes, England; and WHEREAS, Upon the completion of his studies at the local King Edward VI School, Donald Moffat performed national service with the Royal Artillery from 1949 to 1951; he went on to study at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London until 1954; and WHEREAS, This extraordinary stage, screen and television actor was a naturalized, thoroughly Americanized Englishman who in the early 1950s was a player with the Old Vic theater company, the London crucible of many of Britain's most ambitious performing arts; and WHEREAS, In 1956, at the age of 26, Donald Moffat realized his dream and moved to the United States, settling in Oregon, where he worked as a bartender and a lumberjack; he soon resolved to return to acting, and made his Broadway debut as two characters in "Under Milkwood" (1957); and WHEREAS, -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

Biography of Eugene O'neill

Biography of Eugene O’Neill Trevor M. Wise Eugene Gladstone O’Neill was born on October 16, 1888, at the Barrett hotel in New York city, New York, son of James o’Neill, a well-known matinee idol, and Mary Ellen (Ella) Quinlan. Much of O’Neill’s youth was spent in the wings of the theater as he toured the country with his parents and older brother Jamie, watching his father perform his most famous role—the Count of Monte Cristo. When not touring the country with his family, O’Neill attended Catholic boarding school at St. Aloysius Academy at Mount Saint Vincent in the Bronx borough of New York. he then spent four years at Betts Academy, a non-sectarian prep school in Stamford, Connecticut. O’Neill spent the summers with his family at the Monte Cristo Cottage in New London, Connecticut, the only permanent home O’Neill knew as a child. in 1903, at the age of fifteen, o’Neill became aware of his mother’s morphine addiction and was introduced to alcohol by his brother Jamie, setting him on a path of heavy drinking and alcohol abuse. in the fall of 1906, o’Neill enrolled in princeton University, only to be expelled in the following spring for his poor academic per- formance. in october 1909, o’Neill secretly married Kathleen Jenkins, his first of three wives. Shortly after the wedding, o’Neill set sail for honduras to prospect for gold, but found none. While abroad, O’Neill lived the life of a waterfront derelict, working odd jobs and drinking heavily, until he contracted malaria and was forced to return to the United States. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

Comes to Life in ELLA, a Highly-Acclaimed Musical Starring Tina Fabrique Limited Engagement

February 23, 2011 Jazz’s “First Lady of Song” comes to life in ELLA, a highly-acclaimed musical starring Tina Fabrique Limited engagement – March 22 – 27, 2011 Show features two dozen of the famed songstresses’ greatest hits (Philadelphia, February 23, 2011) — Celebrate the “First Lady of Song” Ella Fitzgerald when ELLA, the highly-acclaimed musical about legendary singer Ella Fitzgerald, comes to Philadelphia for a limited engagement, March 22-27, 2011, at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts. Featuring more than two-dozen hit songs, ELLA combines myth, memory and music into a stylish and sophisticated journey through the life of one of the greatest jazz singers of the 20th century. Broadway veteran Tina Fabrique, under the direction of Rob Ruggiero (Broadway: Looped starring Valerie Harper, upcoming High starring Kathleen Turner), captures the spirit and exuberance of the famed singer, performing such memorable tunes as “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” “That Old Black Magic,” “They Can’t Take That Away from Me” and “It Don’t Mean A Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing).” ELLA marks the first time the Annenberg Center has presented a musical as part of its theatre series. Said Annenberg Center Managing Director Michael J. Rose, “ELLA will speak to a wide variety of audiences including Fitzgerald loyalists, musical theatre enthusiasts and jazz novices. We are pleased to have the opportunity to present this truly unique production featuring the incredible vocals of Tina Fabrique to Philadelphia audiences.” Performances of ELLA take place on Tuesday, March 22 at 7:30 PM; Thursday, March 24 at 7:30 PM; Friday, March 25 at 8:00 PM; Saturday, March 26 at 2:00 PM & 8:00 PM; and Sunday, March 27 at 2:00 PM.