Exlibris DP.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Padis Opeda Ballet

FREDERICK WISEMAN BIOGRAPHY Frederick Wiseman is an American filmmaker, born on January 1969, Hospital in 1970, Juvenile Court in 1973 and Welfare 1st, 1930, in Boston, Massachusetts. A documentary filmmaker, in 1975. In addition to Zoo (1993), he directed three other most of his films paint a portrait of leading North American documentaries on our relationship with the animal world: Primate institutions. in 1974, Meat in 1976 and Racetrack in 1985 respectively about After studying law he started teaching the subject without any real scientific experiments on animals, the mass production of beef interest. In decided he should work at something he liked and had cattle destined for the slaughterhouse and consumers and the the idea to make a movie of Warren Miller’s novel, The Cool World. Belmont racetrack one of the major American racetracks. Since at that point he had no film experience he asked Shirley He began an examination of the consumer society with Model in Clarke to direct the film. ProducingThe Cool World demystified the 1980 and The Store in 1983. The sharpness of his gaze, his biting film making process for him and he decided to direct, produce and humour and his compassion characterize his exploration of the edit his own films. Three years later came the theatrical release of model agency and the big store Neiman Marcus, temples of western his first documentary,Titicut Follies, an uncompromising look at a modernity. In 1995, he slipped into the wings of the theatre and prison for the criminally insane. directed La Comédie-Française ou l’amour joué. -

Frederick Wiseman

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 15 | 2017 Lolita at 60 / Staging American Bodies Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Cinémathèque de Toulouse, 19 mai 2017 /Organisée par Zachary Baqué (CAS) et Vincent Souladié (PLH) Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10953 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.10953 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean, « Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » », Miranda [En ligne], 15 | 2017, mis en ligne le 04 octobre 2017, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10953 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda. 10953 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. provided by OpenEdition View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » 1 Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Cinémathèque de Toulouse, 19 mai 2017 /Organisée par Zachary Baqué (CAS) et Vincent Souladié (PLH) Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean 1 Organisée par les laboratoires CAS et PLH, en association avec la Cinémathèque de Toulouse, cette journée d’étude consacrée à Frederick Wiseman se propose d’aborder l’œuvre dense d’un cinéaste américain majeur du genre documentaire, reconnu tant par la critique que par ses pairs, mais dont les films (Titicut Follies (1967), Primate (1974) et Public Housing (1997) pour citer les plus connus) sont paradoxalement peu vus. -

Documentaries Feature Length

feature length documentaries LIBRARY best of fests OSCAR NOMINEE LOCARNO HALE COUNTY THIS FOR BEST DOC EACH AND EVERY CÉSAR NOMINEE MORNING, THIS EVENING SUNDANCE MOMENT FOR BEST DOC by RaMell Ross by Nicolas Philibert Composed of intimate and unencumbered moments of Each And Every Moment follows young women and men in people in a community, this film is constructed in a form nurshing school with the ups and downs of an apprenticeship that allows the viewer an emotive impression of the Historic that confronts them with the life in all its complexities. South - trumpeting the beauty of life and consequences of the social construction of race, while simultaneously existing as a testament to dreaming - despite the odds. By the same director: Easter Snap - 14' / 2018 Idiom Film - Louverture Films / USA / 76' / 2018 Archipel 35 - Longride / France - Japan / 105' / 2018 CANNES SPECIAL SCREENING CANNES DEAD SOULS TORONTO HISSEIN HABRÉ, TORONTO by Wang Bing A CHADIAN TRAGEDY NYFF In Gansu Province, northwest China, lie the remains of by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun countless prisoners abandoned in the Gobi Desert sixty years ago. Designated as "ultra-rightists" in the Communist Party's In 2013, former Chadian dictator Hissein Habré's arrest in Anti-Rightist campaign of 1957, they starved to death in the Senegal marked the end of a long combat for the survivors of Jiabiangou and Mingshui reeducation camps. The film invites his regime. Accompanied by the Chairman of the Association us to meet the survivors of the camps to find out firsthand of the Victims of the Hissein Habré Regime, Mahamat Saleh who these persons were, the hardships they were forced to Haroun goes to meet those who survived this tragedy and endure and what became their destiny. -

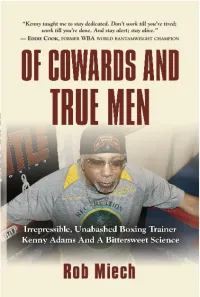

Of Cowards and True Men Order the Complete Book From

Kenny Adams survived on profanity and pugilism, turning Fort Hood into the premier military boxing outfit and coaching the controversial 1988 U.S. Olympic boxing team in South Korea. Twenty-six of his pros have won world-title belts. His amateur and professional successes are nonpareil. Here is the unapologetic and unflinching life of an American fable, and the crude, raw, and vulgar world in which he has flourished. Of Cowards and True Men Order the complete book from Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/8941.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Enjoy your free excerpt below! Of Cowards and True Men Rob Miech Copyright © 2015 Rob Miech ISBN: 978-1-63490-907-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., Bradenton, Florida, U.S.A. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2015 First Edition I URINE SPRAYS ALL over the black canvas. A fully loaded Italian Galesi-Brescia 6.35 pearl-handled .25-caliber pistol tumbles onto the floor of the boxing ring. Just another day in the office for Kenny Adams. Enter the accomplished trainer’s domain and expect anything. “With Kenny, you never know,” says a longtime colleague who was there the day of Kenny’s twin chagrins. First off, there’s the favorite word. Four perfectly balanced syllables, the sweet matronly beginning hammered by the sour, vulgar punctuation. -

Untersucht an Einem Film Von Frederick Wiseman

Abschlussarbeit zur Erlangung der Magistra Artium im Fachbereich Theater-, Film und Medienwissenschaft der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main Institut für Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Repräsentationsformen des Direct Cinema – untersucht an einem Film von Frederick Wiseman 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Heide Schlüpmann 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Burkhardt Lindner vorgelegt von: Esther Zeschky aus: Schotten Einreichungsdatum: 09. 07. 2002 1 Antje, für alles. Thank You! 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung 4 2. Vom non-fiction-Film zur documentary Frühe Formen des Dokumentarfilms 8 3. Das amerikanische Direct Cinema der 60er Jahre 17 3.1 Einflüsse auf das Direct Cinema 24 3.2 Ästhetik, Authentizität und Objektivität im Direct Cinema 41 3.3 Die Drew Associates 45 3.3.1 Die Erzählstruktur der Drew-Filme 52 3.3.2 Leacocks und Pennebakers Trennung von den Drew Associates und andere Filmemacher des Direct Cinema 55 4. Der Dokumentarfilmer Frederick Wiseman 57 4.1 Frederick Wisemans Vorgehensweise 64 4.2 Analyse des Films High School (1968) 69 5. Schlussbemerkung 83 6. Literaturverzeichnis 89 7. Anhang 85 Segmentierung des Films High School (1968) 96 Abbildungen 101 Frederick Wiseman’s Documentary Films 102 3 1. Einleitung Every film is a documentary. Even the most whimsical of fictions gives evidence of the culture that produced it and reproduces the likenesses of the people who perform within it. In fact, we could say that there are two kinds of film: (1) documentaries of wish-fulfillment and (2) documentaries of social representation. Each type tells a story, but the stories, or narratives, are of different sorts.1 Wie Bill Nichols in obigem Zitat treffend zum Ausdruck bringt, gibt es keine scharfe Trennungslinie zwischen Dokumentarfilm und Spielfilm. -

COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media Notes from and about Barnouw’s Documentary: A history of the non-fiction film 11. Documentarist as. Observer Definition(s): [British] Free Cinema—A series of showings at London’s National Film Theater, 1956-58 with films by such filmmakers as Lindsay Anderson (primarily known for his narrative films If. ., O Lucky Man), Karel Reisz & Tony Richardson (primarily known for his narrative films The Entertainer, Tom Jones), and Georges Franju (see below); characterized by filmmakers acting as observers, rejecting the role of promoter; made possible by new, light film equipment that allowed an intimacy of observation new to documentary (including both sound and image). [American] Direct Cinema—A term coined by filmmaker Albert Maysles, this is another type of “observer” documentary that attempts to limit the apparent involvement of the filmmaker, using little or no voiceover narration, no script, and no “setting up” subjects (stagings) or reenactments. As David Maysles has indicated, “direct” means “there’s nothing between us and the subject.” Following the British Free Cinema, the American Direct Cinema took advantage of the new, maneuverable 16mm film equipment; after a series of experiments, a wireless synchronizing sound system for this equipment was developed by the Drew Unit at Time, Inc. The main Documentarists: Robert Drew, Ricky Leacock, D. A. Pennebaker, David & Albert Maysles (and associates), Frederick Wiseman. The influence of Direct Cinema has been felt around the world (e.g., prominent films from Holland, Japan, India, Sweden, Canada). [French] Cinema Verite—According to Barnouw, this term is reserved for films following Jean Rouch’s notions of filmmaker as avowed participant, as provocateur (as what Barnouw calls catalyst), rather than the cool detachment of the Direct Cinema. -

Film Studies

Film Studies SAMPLER INCLUDING Chapter 5: Rates of Exchange: Human Trafficking and the Global Marketplace From A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film Edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow Chapter 27: The World Viewed: Documentary Observing and the Culture of Surveillance From A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film Edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow Chapter 14: Nairobi-based Female Filmmakers: Screen Media Production between the Local and the Transnational From A Companion to African Cinema Edited by Kenneth W. Harrow and Carmela Garritano 5 Rates of Exchange Human Trafficking and the Global Marketplace Leshu Torchin Introduction1 Since 1992, the world has witnessed significant geopolitical shifts that have exacer- bated border permeability. The fall of the “iron curtain” in Eastern Europe and the consolidation of the transnational constitutional order of the European Union have facilitated transnational movement and given rise to fears of an encroaching Eastern threat, seen in the Polish plumber of a UKIP2 fever dream. Meanwhile, global business and economic expansion, granted renewed strength through enhance- ments in communication and transportation technologies as well as trade policies implemented through international financial institutions, have increased demand for overseas resources of labor, goods, and services. This is not so much a new phenomenon, as a rapidly accelerating one. In the wake of these changes, there has been a resurgence of human trafficking films, many of which readily tap into the gendered and racialized aspects of the changing social landscape (Andrjasevic, 2007; Brown et al., 2010). The popular genre film, Taken (Pierre Morel, France, 2008) for instance, invokes the multiple anxieties in a story of a young American girl who visits Paris only to be kidnapped by Albanian mobsters and auctioned off to Arab sheiks before she is rescued by her renegade, one-time CIA agent father. -

Frederick Wiseman : Titicut Follies Est Une Comédie Musicale! »

ENTRETIENS Baumann, Fabien. « Entretien avec Frederick Wiseman : Titicut Follies est une comédie musicale! ». Positif, no 581-582, juillet-août 2009, pp.66-68. Ill. Le réalisateur Frederick Wiseman commente son film TITICUT FOLLIES et sa façon de présenter la folie. Repères bibliographiques 81 Béghin, Cyril. « Wiseman sur le ring ». Cahiers du Cinéma, no 656, mai 2010, pp.34-35. Ill. Le réalisateur Frederick Wiseman parle de son documentaire BOXING GYM, à l’occasion de sa projection au Festival de Cannes. Frederick Wiseman Mikles, Laetitia ; Lévy, Delphine. « Entretien avec Frederick Wiseman : un de 9 au 20 novembre 2011 mes films les plus abstraits ». Positif, no 608, octobre 2011, pp.37-41. Entretien avec Frederick Wiseman à propos de son film CRAZY HORSE, où le cinéaste présente l’origine du projet et l’approche qu’il a préconisée lors du tournage. Peary, Gerald ; Mikles, Laetitia. « Une leçon de sociologie : l'oeuvre de Frederick Wiseman ; Frederick Wiseman : "Je suis incapable de prononcer des vérités générales" ». Positif, no 445, mars 1998, pp.86-95. Ill. Analyse de l'oeuvre du documentariste Frederick Wiseman, accompagnée d'un entretien. Le cinéaste parle de ses méthodes de travail, de sa conception du documentaire et de la réalisation de PUBLIC HOUSING. Rapold, Nicolas. « The organisation man ». Sight & Sound, vol XIX, no 11, novembre 2009, p.23. Ill. Entretien avec Frederick Wiseman à propos de son film LA DANSE, LE BALLET DE L’OPÉRA DE PARIS, où il est notamment question de l’intérêt du cinéaste envers l’organisation entourant cette troupe de danse, et de sa première utilisation du logiciel Avid pour le montage de ce film. -

Frederick Wiseman: MONROVIA, INDIANA (2018, 143M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

April 30, 2019 (XXXVIII: 13) Frederick Wiseman: MONROVIA, INDIANA (2018, 143m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Frederick Wiseman PRODUCED BY Frederick Wiseman CINEMATOGRAPHY John Davey EDITING Frederick Wiseman SOUND EDITOR Valérie Pico FREDERICK WISEMAN (b. January 1, 1930 in Boston, Massachusetts) is an American documentary filmmaker (47 credits). His work is "devoted primarily to exploring American institutions.” He has been called "one of the most important and original filmmakers working today” (New York Times). After graduating from Yale Law School in 1954, Wiseman served in the military before taking a teaching position at Boston University Institute of Law and Medicine. It was at this time that he also began pursuing documentary filmmaking. He has received honorary doctorates from Bowdoin College, Princeton University, and Williams College, among others. He is a MacArthur Fellow, a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, an Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a recipient of a Guggenheim structure.” The notion that he is interested in finding a narrative Fellowship. He has won numerous awards, including four angle also complements his view that it is impossible for a Emmys. He is also the recipient of the Career Achievement documentary filmmaker to be completely objective or unbiased Award from the Los Angeles Film Society (2013), the in relation to his or her subject. -

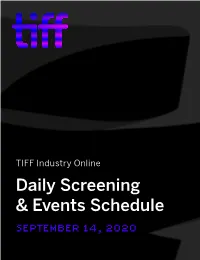

Daily Screening & Events Schedule

TIFF Industry Online Daily Screening & Events Schedule SEPTEMBER 14, 2020 TORONTO’S LARGEST PURPOSE-BUILT STUDIO The leading destination facility for f ilm and TV production New space coming soon Talk to us: t: +1 416 406 1235 e: [email protected] For further information on our studio, please visit: www.pinewoodtorontostudios.com I Industry user access P Press user access Press & Industry B Buyer user access * Availability per country on the schedule at TIFF.NET/INDUSTRY Daily Schedule Access TIFF Digital Cinema Pro September 14, 2020 at DIGITALPRO.TIFF.NET NEW TODAY Films are available for 48 hours from start time. 10 AM BECKMAN NEUBAU PIRATES DOWN THE STREET SWEAT EDT 90 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro 82 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro 90 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro 80 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro Private Screening Private Screening Private Screening TIFF Industry Selects I P B P B I B I P B FAIRY THE NORTH WIND RIVAL TELEFILM CANADA FIRST LOOK 152 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro 122 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro 96 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro 51 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro Private Screening Private Screening Private Screening Private Screening B B B I B LOVERS PEARL OF THE DESSERT SHOULD THE WIND DROP WISDOM TOOTH 102 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro 86 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro 100 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro 104 min. | TIFF Digital Cinema Pro TIFF Industry Selects Private Screening TIFF Industry Selects Private Screening B I P B I P B I B 11 AM BANDAR BAND CITY HALL GOOD JOE BELL TRICKSTER EDT 75 min. -

11. Documentarist As. . . Observer

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television Notes from and about Barnouw’s Documentary: A history of the non-fiction film 11. Documentarist as. Observer Definition(s): Free Cinema—A series of showings at London’s National Film Theater, 1956-58 with films by such filmmakers as Lindsay Anderson (If. ., O Lucky Man), Karel Reisz & Tony Richardson (The Entertainer, Tom Jones), and Georges Franju (see below); characterized by filmmakers acting as observers, rejecting the role of promoter; made possible by new, light film equipment that allowed an intimacy of observation new to documentary (including both sound and image). Direct Cinema—A term coined by filmmaker Albert Maysles, this is another type of “observer” documentary that attempts to limit the apparent involvement of the filmmaker, using little or no voiceover narration, no script, and no “setting up” subjects (stagings) or reenactments. As David Maysles has indicated, “direct” means “there’s nothing between us and the subject.” Following the British Free Cinema, the American Direct Cinema took advantage of the new, maneuverable 16mm film equipment; after a series of experiments, a wireless synchronizing sound system for this equipment was developed by the Drew Unit at Time, Inc. The main Documentarists: Robert Drew, Ricky Leacock, D. A. Pennebaker, David & Albert Maysles (and associates), Frederick Wiseman. The influence of Direct Cinema has been felt around the world (e.g., prominent films from Holland, Japan, India, Sweden, Canada). Cinema Verite—According to Barnouw, this term is reserved for films following Jean Rouch’s notions of filmmaker as avowed participant, as provocateur (as what Barnouw calls catalyst), rather than the cool detachment of the Direct Cinema. -

The Poetry of Reality: Frederick Wiseman and the Theme of Time

THE POETRY OF REALITY: FREDERICK WISEMAN AND THE THEME OF TIME Blake Jorgensen Wahlert, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2019 APPROVED: Harry M. Benshoff, Major Professor George Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Melinda Levin, Committee Member Eugene Martin, Chair of the Department of Media Arts David Holdeman, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Wahlert, Blake Jorgensen. The Poetry of Reality: Frederick Wiseman and the Theme of Time. Master of Arts (Media Industry and Critical Studies), May 2019, 86 pp., reference list, 74 titles. Employing a textual analysis within an auteur theory framework, this thesis examines Frederick Wiseman’s films At Berkeley (2013), National Gallery (2014), and Ex Libris (2017) and the different ways in which they reflect on the theme of time. The National Gallery, University of California at Berkeley, and the New York Public Library all share a fundamental common purpose: the preservation and circulation of “truth” through time. Whether it be artistic, scientific, or historical truth, these institutions act as cultural and historical safe-keepers for future generations. Wiseman explores these themes related to time and truth by juxtaposing oppositional binary motifs such as time/timelessness, progress/repetition, and reality/fiction. These are also Wiseman’s most self-reflexive films, acting as a reflection on his past filmmaking career as well as a meditation on the value these films might have for future generations. Finally, Wiseman’s reflection on the nature of time through these films are connected to the ideas of French philosopher Henri Bergson.