Text of Diss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Padis Opeda Ballet

FREDERICK WISEMAN BIOGRAPHY Frederick Wiseman is an American filmmaker, born on January 1969, Hospital in 1970, Juvenile Court in 1973 and Welfare 1st, 1930, in Boston, Massachusetts. A documentary filmmaker, in 1975. In addition to Zoo (1993), he directed three other most of his films paint a portrait of leading North American documentaries on our relationship with the animal world: Primate institutions. in 1974, Meat in 1976 and Racetrack in 1985 respectively about After studying law he started teaching the subject without any real scientific experiments on animals, the mass production of beef interest. In decided he should work at something he liked and had cattle destined for the slaughterhouse and consumers and the the idea to make a movie of Warren Miller’s novel, The Cool World. Belmont racetrack one of the major American racetracks. Since at that point he had no film experience he asked Shirley He began an examination of the consumer society with Model in Clarke to direct the film. ProducingThe Cool World demystified the 1980 and The Store in 1983. The sharpness of his gaze, his biting film making process for him and he decided to direct, produce and humour and his compassion characterize his exploration of the edit his own films. Three years later came the theatrical release of model agency and the big store Neiman Marcus, temples of western his first documentary,Titicut Follies, an uncompromising look at a modernity. In 1995, he slipped into the wings of the theatre and prison for the criminally insane. directed La Comédie-Française ou l’amour joué. -

Come In-The Water's Fine

May 26, 1961 THE PHOENIX JEWISH NEWS Page 3 Final Scores JEWS IN SPORTS Boxing Story SPORT In Bowling HTie AfSinger BY HAROLD U. RIBALOW was the big night of Singer’s ca- reer. More than 35,000 fans crowd- SCOOP NEW YORK, (JTA)—The death ed into Yankee Stadium, paying By RONfclE PIES him in the 440. Throughout the of former lightweight the title fight be- gap. With 10 Announced last month $160,000 to see goal race Art closed the boxing champion A1 Singer was a tween Singer and the lightweight In keeping with the prime yards remaining, he passed his op- Final season scores in B'nai to all who follow the sport. champion, 26-year-old Sammy of this series, which is to give rec- ponent pulled away to win. blow the of Phoe- and B’rith bowling leagues have been Al Singer was known as a boxer Mandell. The champ was a ten- ognition to Jewish athletes TO COMPLETE his high school Singer nix and Arizona, we will honor a announced: with a “glass jaw.” This is an year veteran of the ring; career, Art was invited to a na- disease, which means three years of fighting different athlete in each article. tional championship meet in Los Majors league Carl Slonsky, occupational had only chosen that a man has a physical weak- behind him. The first person we have Angeles to compete with some of high individual series of 665; Jack the A shot at the jaw out cautiously, to honor is Art Gardenswartz, Uni- in the 269. -

Frederick Wiseman

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 15 | 2017 Lolita at 60 / Staging American Bodies Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Cinémathèque de Toulouse, 19 mai 2017 /Organisée par Zachary Baqué (CAS) et Vincent Souladié (PLH) Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10953 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.10953 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean, « Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » », Miranda [En ligne], 15 | 2017, mis en ligne le 04 octobre 2017, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10953 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda. 10953 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. provided by OpenEdition View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » 1 Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Cinémathèque de Toulouse, 19 mai 2017 /Organisée par Zachary Baqué (CAS) et Vincent Souladié (PLH) Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean 1 Organisée par les laboratoires CAS et PLH, en association avec la Cinémathèque de Toulouse, cette journée d’étude consacrée à Frederick Wiseman se propose d’aborder l’œuvre dense d’un cinéaste américain majeur du genre documentaire, reconnu tant par la critique que par ses pairs, mais dont les films (Titicut Follies (1967), Primate (1974) et Public Housing (1997) pour citer les plus connus) sont paradoxalement peu vus. -

An Analysis of Tiger Woods' Image Restoration Efforts

SAVING PAR: AN ANALYSIS OF TIGER WOODS’ IMAGE RESTORATION EFFORTS IN RESPONSE TO ALLEGATIONS OF MARITAL INFIDELITIES A Thesis by Dustin Kyle Martin Wiens Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2009 Submitted to the Department of Communication and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts July 2012 © Copyright 2012 by Dustin Kyle Martin Wiens All Rights Reserved SAVING PAR: AN ANALYSIS OF TIGER WOODS’ IMAGE RESTORATION EFFORTS IN RESPONSE TO ALLEGATIONS OF MARITAL INFIDELITIES The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Communication. _____________________________________ Jeffrey Jarman, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Lisa Parcell, Committee Member _____________________________________ Carolyn Shaw, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my parents iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express the utmost gratitude to my adviser, Jeff Jarman. He has always been there for me throughout my undergraduate and graduate career alike, as a professor, debate coach and friend. I would also like to thank Carolyn Shaw and Lisa Parcell for their willingness to serve on my thesis committee and for all their help over the years to help me mature into the student and writer that I have become. v ABSTRACT This research describes and analyzes the rhetorical choices made by Tiger Woods in response to the allegations of marital infidelity. This thesis uses qualitative methodology to analyze the image restoration efforts used by Woods to combat this crisis situation. -

Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want to Share: an Analysis of Antitrust Issues Surrounding Boxing and Mixed Martial Arts and Ways to Improve Combat Sports

Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 5 8-1-2018 Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want To Share: An Analysis of Antitrust Issues Surrounding Boxing and Mixed Martial Arts and Ways to Improve Combat Sports Daniel L. Maschi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel L. Maschi, Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want To Share: An Analysis of Antitrust Issues Surrounding Boxing and Mixed Martial Arts and Ways to Improve Combat Sports, 25 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 409 (2018). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol25/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\25-2\VLS206.txt unknown Seq: 1 26-JUN-18 12:26 Maschi: Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want To Share: An Analysis of Antitr MILLION DOLLAR BABIES DO NOT WANT TO SHARE: AN ANALYSIS OF ANTITRUST ISSUES SURROUNDING BOXING AND MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND WAYS TO IMPROVE COMBAT SPORTS I. INTRODUCTION Coined by some as the “biggest fight in combat sports history” and “the money fight,” on August 26, 2017, Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) mixed martial arts (MMA) superstar, Conor McGregor, crossed over to boxing to take on the biggest -

Documentaries Feature Length

feature length documentaries LIBRARY best of fests OSCAR NOMINEE LOCARNO HALE COUNTY THIS FOR BEST DOC EACH AND EVERY CÉSAR NOMINEE MORNING, THIS EVENING SUNDANCE MOMENT FOR BEST DOC by RaMell Ross by Nicolas Philibert Composed of intimate and unencumbered moments of Each And Every Moment follows young women and men in people in a community, this film is constructed in a form nurshing school with the ups and downs of an apprenticeship that allows the viewer an emotive impression of the Historic that confronts them with the life in all its complexities. South - trumpeting the beauty of life and consequences of the social construction of race, while simultaneously existing as a testament to dreaming - despite the odds. By the same director: Easter Snap - 14' / 2018 Idiom Film - Louverture Films / USA / 76' / 2018 Archipel 35 - Longride / France - Japan / 105' / 2018 CANNES SPECIAL SCREENING CANNES DEAD SOULS TORONTO HISSEIN HABRÉ, TORONTO by Wang Bing A CHADIAN TRAGEDY NYFF In Gansu Province, northwest China, lie the remains of by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun countless prisoners abandoned in the Gobi Desert sixty years ago. Designated as "ultra-rightists" in the Communist Party's In 2013, former Chadian dictator Hissein Habré's arrest in Anti-Rightist campaign of 1957, they starved to death in the Senegal marked the end of a long combat for the survivors of Jiabiangou and Mingshui reeducation camps. The film invites his regime. Accompanied by the Chairman of the Association us to meet the survivors of the camps to find out firsthand of the Victims of the Hissein Habré Regime, Mahamat Saleh who these persons were, the hardships they were forced to Haroun goes to meet those who survived this tragedy and endure and what became their destiny. -

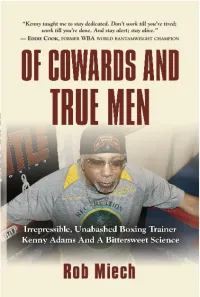

Of Cowards and True Men Order the Complete Book From

Kenny Adams survived on profanity and pugilism, turning Fort Hood into the premier military boxing outfit and coaching the controversial 1988 U.S. Olympic boxing team in South Korea. Twenty-six of his pros have won world-title belts. His amateur and professional successes are nonpareil. Here is the unapologetic and unflinching life of an American fable, and the crude, raw, and vulgar world in which he has flourished. Of Cowards and True Men Order the complete book from Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/8941.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Enjoy your free excerpt below! Of Cowards and True Men Rob Miech Copyright © 2015 Rob Miech ISBN: 978-1-63490-907-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., Bradenton, Florida, U.S.A. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2015 First Edition I URINE SPRAYS ALL over the black canvas. A fully loaded Italian Galesi-Brescia 6.35 pearl-handled .25-caliber pistol tumbles onto the floor of the boxing ring. Just another day in the office for Kenny Adams. Enter the accomplished trainer’s domain and expect anything. “With Kenny, you never know,” says a longtime colleague who was there the day of Kenny’s twin chagrins. First off, there’s the favorite word. Four perfectly balanced syllables, the sweet matronly beginning hammered by the sour, vulgar punctuation. -

\Zt//Firoa Will Not Figure Below .100

* 5 The BROWNSVILLE HERALD SPORTS SECTION HM ■-1 >,ff } **** fr~J Jl rrrJJJ JJJf 11111** f r J< owimmimim rrfrrrrrrri wri—-wimri—rJ rrr rrrrif f f rrrf #*••**»•**—•m*t*t**m»*wmm im"' »#*******’*** * * » * T T T v l Sports SWIMMING l Spade | LIGHTWEIGHT Senators Being Hard Hit on Western Trip .. ..—-X By HAL EUSTACE RECORDS m CROWN IS HIS Gridster Dies • ■■■■■■■■■■■I . GREENVILLE. S. C., July 18.—OF • BRUSHING UP SPORTS By Laufer and A SOLONS FALL 1 —Ernest Holmes. 22. of El Campo, Japanese BIND LOW on folded knee*, oh 18—W—The NEW YORK. July Texas, star tackle of Furman Uni- the College ye faithful ringworms. Do obels- crown of lightweights today football team died in a Athle^* adorns the thick black thatch of 21- versity’s anoe to A1 Singer, lightweight yesterday of complications Shine / year-oid A1 Singer, whose sensa- hospital the TO 2ND PLACE settling In after an operation for champion of a day. Last night tional one round knockout of Sam- appendicitis. ^ Uttle New York idol buzzed my Mandell last night brought back -/ popular HONOLULU. the 135-pound championship to New July from hi* corner a slam-bang, slash- Are Games Behind Loop American York for the first time since Benny 3V2 swimmingj*c.°r<*8h“ T_ ing tornado of action. Before the Leonard retired. bettered here last *» «g^u and A Leaders and 4 Ahead terr.itional meet resonant clang of the ball had The boy from the Bronx pro- CUE Of SAVANNAH, feA^_ f5and Mel of Leonard, making his title SLICED MIS PRIMO’S PAPAS from Yale Univer** sounded for the second time, one tege TSO&SOME DfcivJB Of Yankees of bid at the Yankee Stadium, crushed University JapfB- wftnolulu. -

Medicine, Sport and the Body: a Historical Perspective

Carter, Neil. "Notes." Medicine, Sport and the Body: A Historical Perspective. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 205–248. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849662062.0006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 11:28 UTC. Copyright © Neil Carter 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Notes Introduction 1 J.G.P. Williams (ed.), Sports Medicine (London: Edward Arnold, 1962). 2 J.G.P. Williams, Medical Aspects of Sport and Physical Fitness (London: Pergamon Press, 1965), pp. 91–5. Homosexuality was legalized in 1967. 3 James Pipkin, Sporting Lives: Metaphor and Myth in American Sports Autobiographies (London: University of Missouri Press, 2008), pp. 44–50. 4 Paula Radcliffe, Paula: My Story So Far (London: Simon & Schuster, 2004). 5 Roger Cooter and John Pickstone, ‘Introduction’ in Roger Cooter and John Pickstone (eds), Medicine in the Twentieth Century (Amsterdam: Harwood, 2000), p. xiii. 6 Barbara Keys, Globalizing Sport: National Rivalry and International Community in the 1930s (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2006), p. 9. 7 Richard Holt, Sport and the British: A Modern History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 3. 8 Deborah Brunton, ‘Introduction’ in Deborah Brunton (ed.), Medicine Transformed: Health, Disease and Society in Europe, 1800–1930 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), p. xiii. 9 Cooter and Pickstone, ‘Introduction’ in Cooter and Pickstone (eds), p. xiv. 10 Patricia Vertinsky, ‘What is Sports Medicine?’ Journal of Sport History , 34:1 (Spring 2007), p. -

Ring Magazine

The Boxing Collector’s Index Book By Mike DeLisa ●Boxing Magazine Checklist & Cover Guide ●Boxing Films ●Boxing Cards ●Record Books BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INSERT INTRODUCTION Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 2 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INDEX MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS Ring Magazine Boxing Illustrated-Wrestling News, Boxing Illustrated Ringside News; Boxing Illustrated; International Boxing Digest; Boxing Digest Boxing News (USA) The Arena The Ring Magazine Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Digest Fight game Flash Bang Marie Waxman’s Fight Facts Boxing Kayo Magazine World Boxing World Champion RECORD BOOKS Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 3 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK RING MAGAZINE [ ] Nov Sammy Mandell [ ] Dec Frankie Jerome 1924 [ ] Jan Jack Bernstein [ ] Feb Joe Scoppotune [ ] Mar Carl Duane [ ] Apr Bobby Wolgast [ ] May Abe Goldstein [ ] Jun Jack Delaney [ ] Jul Sid Terris [ ] Aug Fistic Stars of J. Bronson & L.Brown [ ] Sep Tony Vaccarelli [ ] Oct Young Stribling & Parents [ ] Nov Ad Stone [ ] Dec Sid Barbarian 1925 [ ] Jan T. Gibbons and Sammy Mandell [ ] Feb Corp. Izzy Schwartz [ ] Mar Babe Herman [ ] Apr Harry Felix [ ] May Charley Phil Rosenberg [ ] Jun Tom Gibbons, Gene Tunney [ ] Jul Weinert, Wells, Walker, Greb [ ] Aug Jimmy Goodrich [ ] Sep Solly Seeman [ ] Oct Ruby Goldstein [ ] Nov Mayor Jimmy Walker 1922 [ ] Dec Tommy Milligan & Frank Moody [ ] Feb Vol. 1 #1 Tex Rickard & Lord Lonsdale [ ] Mar McAuliffe, Dempsey & Non Pareil 1926 Dempsey [ ] Jan -

Film Studies

Film Studies SAMPLER INCLUDING Chapter 5: Rates of Exchange: Human Trafficking and the Global Marketplace From A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film Edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow Chapter 27: The World Viewed: Documentary Observing and the Culture of Surveillance From A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film Edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow Chapter 14: Nairobi-based Female Filmmakers: Screen Media Production between the Local and the Transnational From A Companion to African Cinema Edited by Kenneth W. Harrow and Carmela Garritano 5 Rates of Exchange Human Trafficking and the Global Marketplace Leshu Torchin Introduction1 Since 1992, the world has witnessed significant geopolitical shifts that have exacer- bated border permeability. The fall of the “iron curtain” in Eastern Europe and the consolidation of the transnational constitutional order of the European Union have facilitated transnational movement and given rise to fears of an encroaching Eastern threat, seen in the Polish plumber of a UKIP2 fever dream. Meanwhile, global business and economic expansion, granted renewed strength through enhance- ments in communication and transportation technologies as well as trade policies implemented through international financial institutions, have increased demand for overseas resources of labor, goods, and services. This is not so much a new phenomenon, as a rapidly accelerating one. In the wake of these changes, there has been a resurgence of human trafficking films, many of which readily tap into the gendered and racialized aspects of the changing social landscape (Andrjasevic, 2007; Brown et al., 2010). The popular genre film, Taken (Pierre Morel, France, 2008) for instance, invokes the multiple anxieties in a story of a young American girl who visits Paris only to be kidnapped by Albanian mobsters and auctioned off to Arab sheiks before she is rescued by her renegade, one-time CIA agent father. -

Copyright by Tyler David Fleming 2009

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UT Digital Repository Copyright by Tyler David Fleming 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Tyler David Fleming Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “King Kong, Bigger Than Cape Town”: A History of a South African Musical Committee: Toyin Falola, Supervisor Barbara Harlow Karl Hagstrom Miller Juliet E. K. Walker Steven J. Salm “King Kong, Bigger than Cape Town”: A History of a South African Musical by Tyler David Fleming, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2009 Dedication For my parents because without them, I literally would not be here. “King Kong, Bigger Than Cape Town”: A History of a South African Musical Publication No._____________ Tyler David Fleming, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2009 Supervisor: Oloruntoyin Falola This dissertation analyzes the South African musical, King Kong , and its resounding impact on South African society throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. A “jazz opera” based on the life of a local African boxer (and not the overgrown gorilla from American cinema), King Kong featured an African composer and all-black cast, including many of the most prominent local musicians and singers of the era. The rest of the play’s management, including director, music director, lyricist, writer and choreographer, were overwhelmingly white South Africans.