The Poetry of Reality: Frederick Wiseman and the Theme of Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Padis Opeda Ballet

FREDERICK WISEMAN BIOGRAPHY Frederick Wiseman is an American filmmaker, born on January 1969, Hospital in 1970, Juvenile Court in 1973 and Welfare 1st, 1930, in Boston, Massachusetts. A documentary filmmaker, in 1975. In addition to Zoo (1993), he directed three other most of his films paint a portrait of leading North American documentaries on our relationship with the animal world: Primate institutions. in 1974, Meat in 1976 and Racetrack in 1985 respectively about After studying law he started teaching the subject without any real scientific experiments on animals, the mass production of beef interest. In decided he should work at something he liked and had cattle destined for the slaughterhouse and consumers and the the idea to make a movie of Warren Miller’s novel, The Cool World. Belmont racetrack one of the major American racetracks. Since at that point he had no film experience he asked Shirley He began an examination of the consumer society with Model in Clarke to direct the film. ProducingThe Cool World demystified the 1980 and The Store in 1983. The sharpness of his gaze, his biting film making process for him and he decided to direct, produce and humour and his compassion characterize his exploration of the edit his own films. Three years later came the theatrical release of model agency and the big store Neiman Marcus, temples of western his first documentary,Titicut Follies, an uncompromising look at a modernity. In 1995, he slipped into the wings of the theatre and prison for the criminally insane. directed La Comédie-Française ou l’amour joué. -

Hamptons Doc Fest 2020 Congratulations on 13 Years of Championing Documentary Films!

Art: Nofa Aji Zatmiko ALL DOCS ALL DAY DOCS ALL ALL OPENING NIGHT FILM: MLK/FBI Hamptons Doc Fest DECEMBER 4–13, 2020 www.hamptonsdocfest.com is a year we will long Wiseman and his newest film, City Hall. 2020 rememberWELCOME or want LETTER to He stands as one of the documentary forget. Deprived of a movie theater’s giants that every aspiring filmmaker magic we struggled to take the virtual learns from, that Wiseman way of plunge. Ultimately, we decided on yes observing life unfold. Our Award films we can to bring you our 13th festival capture the essence of Art & Music, in these overwhelming times. We Human Rights, and the Environment. programmed 35 great documentary Our Opening night film reveals a hidden films to watch in the warmth and chapter in Martin Luther King’s world. comfort of your home over 10 days. No New this year, you’ll hear and see UP worries about weather, parking, ticket CLOSE video clips presented by the lines, where to catch a snack between Directors of each film. My thanks to an films. You can schedule your own day extraordinary team, and to our Artistic the way you like it. Consider it not Director, Karen Arikian. Lastly, you will only a festival experience but a virtual find all the information and help you’ll festival experiment. need to watch films on your television, When Covid hit, Hamptons Doc Fest tablet or computer. So click on and went into overdrive. We were forced step into the big virtual world wherever to cancel our Docs Equinox Spring you are. -

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1972-1973

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1972-1973 Eastern Kentucky University Year 1972 Eastern Progress - 21 Sep 1972 Eastern Kentucky University This paper is posted at Encompass. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress 1972-73/5 r i - • Opposing View Open House Page 2 Page 9 .• / Setting The Pace In A Progressive Era "7 Vo/. No. 50 Issue No. 5- Student Publication of Eastern Kentucky University 10 Pages Thursday, September 21, 1972 UK, UL Get endorsement KCC Study Threatens LEN Programs answer the questions raised in million law enforcement in- The Crane study proposed in criminalistics or crime BY ROBERT BABBAGE the future. stitute at Eastern. that UK offer a Ph. D. in social detention. Managing Editor University officials spent professions to provide The study also suggests that A study done for the Kentucky Bulletin several years precisely researchers and faculty' for the Eastern cater to the needs to Crime Commission has A vote of confidence for Dr. designing the institute. Two statewide program, according eastern Kentucky, while suggested that the University Robert Martin and the Eastern years ago the plan was clearly to a story in the Courier- Western cares for its School of Law Enforcement of Kentucky and the University on paper. The preliminary work Journal. surrounding area. UK and UL came late last night from the cost $281,000. would handle the urban areas. of Louisville be developed as board of directors of the Ken- UK and UL would also offer Don Denginger of the Ken- graduate education centers in cucky Peace Officers The nine-month study of law enforcement. -

Frederick Wiseman

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 15 | 2017 Lolita at 60 / Staging American Bodies Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Cinémathèque de Toulouse, 19 mai 2017 /Organisée par Zachary Baqué (CAS) et Vincent Souladié (PLH) Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10953 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.10953 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean, « Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » », Miranda [En ligne], 15 | 2017, mis en ligne le 04 octobre 2017, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10953 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda. 10953 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. provided by OpenEdition View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » 1 Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Cinémathèque de Toulouse, 19 mai 2017 /Organisée par Zachary Baqué (CAS) et Vincent Souladié (PLH) Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean 1 Organisée par les laboratoires CAS et PLH, en association avec la Cinémathèque de Toulouse, cette journée d’étude consacrée à Frederick Wiseman se propose d’aborder l’œuvre dense d’un cinéaste américain majeur du genre documentaire, reconnu tant par la critique que par ses pairs, mais dont les films (Titicut Follies (1967), Primate (1974) et Public Housing (1997) pour citer les plus connus) sont paradoxalement peu vus. -

Cinema Vérité & Direct Cinema 1960-1970

Cinema Vérité & Direct Cinema 1960-1970 Historical context Cinéma verité: French film movement of the 1960s that showed people in everyday situations with authentic dialogue and naturalness of action. Rather than following the usual technique of shooting sound and pictures together, the filmmaker first tapes actual conversations, interviews and opinions. After selecting the best material, he films the visual material to fit the sound, often using a hand-held camera. The film is then put together in the cutting room. Encyclopedia Britannica Direct Cinema: The invention of relatively inexpensive, portable, but thoroughly professional 16 mm equipment – and the synchronous sound recorder – facilitated the development of a similar movement in the US at just about the same time. Sometimes called cinema verite, sometimes simply ‘direct cinema’, its goal was essentially the capturing of the reality of a person, a moment, or an event without any rearrangement for the camera. Leading American practitioners were Ricky Leacock (Primary, 1960), Frederick Wiseman (Titicut Follies, 1967), Donn Pennebaker (Monterey Pop, 1968) and the Maysles brothers (Salesman, 1969) Encyclopedia Britannica Technological changes Until 1960s synchronous recording of sight & sound on location – difficult to impossible Standard documentary sound-film method - shooting silent - subsequent addition of sound – words, music, sound effects - voice-over commentary (almost) obligatory adds information & interpretation e.g. Grierson, Lorentz This style characterizes documentaries -

Scotch Plains Writer Enjoys Hollywood Hit by Hugh Lilly Dempsey)

VOLUME 30-NUMBER 36 SCOTCH PLAINS-FANWOOD, N.J. SEPTEMBER 10, 1987 30 CENTS SCOTCH PLAINS THE TIMES NUTWOOD Scotch Plains writer enjoys Hollywood hit by Hugh Lilly Dempsey). Ronald simply because of who I "Can't Buy Me Love," achieves his popularity, was with. It was a real the recent film released but loses sight of who he lesson." from Disney, has its roots really is and who he really Swerdlick attended in Scotch Plains! wants to be. American University in Michael Swerdlick, the The working title for Washington, DC after scriptwriter for "Can't the movie was "Balmoral graduating from high Buy Me Love" was raised Lane", the street in the school in 1974. He then here, He graduated from Scotchwood section of went on to law school at the local high school in town where Swerdlick Pepperdine University in 1974 and served as vice grew up. The original pro- Malibu, California. Upon president of . his ducers were using the title graduation, he took a job graduating class, "Boy Rents Girl" until at the William Morris Swerdlick wrote the film Disney purchased the Agency as a talent agent, with "only one place in movie, bought the rights where he spent most of his mind." In fact, he wanted to the Beatles hit from time reading and digesting to have the movie shot Michael Jackson, and scripts of other writers, here, featuring his alma renamed the movie, improving his own sense mater. However, the cost Swerdlick says that of what made a movie suc- prohibited the studio from Michael Eisner (Chairman cessful. -

Charles Musser Mailing Address

11/2/15 Vita Charles Musser-1 Charles Musser mailing address: Box 820 Times Square Station, NY. NY. 10108 Yale tel: 203-432-0152; Yale FAX: 203-432-6764 Cell: 917-880-5321 Email: [email protected] Professional website: http://www.charlesmusser.com/ Education: Yale University, B.A., 1975, Major: Film and Literature New York University, Ph.D., October 1986, Dept. of Cinema Studies Academic Experience: 2000-present: Professor: Yale University. Film & Media Studies, American Studies and Theater Studies. Co-chair, Film Studies Program (to July 2008). Acting Chair, Theater Studies Program, Spring 2013; Director Yale Summer Film Institute. Summer 2012: Visiting Professor: Stockholm University. 1995-2000: Assoc. Prof.: Yale University. American Studies and Film Studies. Director of Undergraduate Studies, Film Studies Program. 1992-1995: Asst. Prof.: Yale University. American Studies and Film Studies. Director of Undergraduate Studies, Film Studies Program. 1985-1995: co-chair: University Seminar, Columbia, on Cinema and Interdisciplinary Interpretation. 1991-1992: Visiting Asst. Prof.: UCLA. Dept. of Film and Television. 1988-1992: Adjunct Asst. Prof.: Columbia University. Film Division, School of the Arts. Spring 1990: Visiting Asst. Prof: New York University. Department of Cinema Studies. 1987-Fall 89: Adjunct Asst. Prof.: New York University. Department of Cinema Studies. Fall 1988: Visiting Adjunct: State University of New York- Purchase. Film Department. Spring 1987: Visiting lecturer: Yale University. College seminar. Curatorial Experience: 2014-present: co-founder NHdocs: the New Haven Documentary and co-director: Film Festival. Over the course of a long weekend, the festival features documentaries from the Greater New Haven Area. In 2015, we screened 23 shorts and features. -

Geographic Guide Alamance County

1 1 GEOGRAPHIC GUIDE ALAMANCE COUNTY GODWIN, PAUL CO INC HOLE-IN-NONE HOSIERY MILL INC t INJECTRONICS INC LEESONA CORP E PO Box 1116 PO Drawer 2198 Frammgham MA Box 2 1 5-B Route 8 E Gilbreath St Ext Graham 1 247 W Webb Ave Burlington Division Tucker St Ext Burlington 27215 Burlington 27215 PO Box 1036 Burlington 27215 Paul Godwin Owner B H Bridges Pres Troxler Road Robert Baker V P Sou Oper Piedmont Region Piedmont Region Established 1959 Burlington 27215 5 333 Strawberry Field Rd I Phone. (919)226-3103 Emp E Phone (919)228-1758 Emp . F Carlos Diaz Gen Mgr Warwick Rl 2679 Recycle paper cones 2252 Finishing mens hosiery 5 3 Speen St Suite 340 Piedmont Region Established 1971 * 26 Used paper cones • 22 Yarn Frammgham MA Phone (919)226-5511 Emp F Piedmont Region Established 1 980 3552 Textile machinery GRA-TEX INC Phone (919)229-7071 Emp E • 35 Textile mach parts PO Box 2163 CO 3089 Custom Injection molding 2127 Chapel Hill Rd HOLLAND MANUFACTURING " 28 Thermoplastic resin Route 2 Box 97 Burlington 27215 LEMCO MILLS INC I * 35 Injection molds Arthur N Tingley, Pres Union Ridge Road P Box 2098 * 26 Corrugated boxes Piedmont Region Established 1972 Burlington 27215 766 Koury Drive * 24 Pallets Phone: (919)228-6479 Emp, E Otis Holland Owner Burlington 27215 2281 Yarn textured Becky Hewett (Export) L H Small Exec VP Piedmont Region J C CUSTOM SEWING * 22 Nylon yarns Piedmont Region Established 1959 Phone: (919)228-8302 Emp P Box C 2503 Phone (919)226-5548 Emp F GRANITE DIAGNOSTICS INC E 2 752 Hosiery packaging pnn ting 1375 N Church St 225 1 Ladies hosiery P Box 908 * 26 Paw stock for printing Burlington 27215 " 22 Synthetic yarns 1308 Rainey St Josephine Vieira Co-Owner Burlington 27215 Piedmont Region Samuel C Powell Pres Phone (919)229-0185 Emp B LIGNA MACHINERY INC HOLT HOSIERY MILLS INC 5 2990 Anthony Road Sporting goods bags PO Box 41 16 Box 1757 2393 Burlington NC 2393 Mac Arthur Lane 2119 W Webb Ave Dye bags Piedmont Region Established 1971 Burlington 27215 Burlington 27215 Phone:(919)226-6311 Emp. -

THE Permanent Crisis of FILM Criticism

mattias FILM THEORY FILM THEORY the PermaNENT Crisis of IN MEDIA HISTORY IN MEDIA HISTORY film CritiCism frey the ANXiety of AUthority mattias frey Film criticism is in crisis. Dwelling on the Kingdom, and the United States to dem the many film journalists made redundant at onstrate that film criticism has, since its P newspapers, magazines, and other “old origins, always found itself in crisis. The erma media” in past years, commentators need to assert critical authority and have voiced existential questions about anxieties over challenges to that author N E the purpose and worth of the profession ity are longstanding concerns; indeed, N T in the age of WordPress blogospheres these issues have animated and choreo C and proclaimed the “death of the critic.” graphed the trajectory of international risis Bemoaning the current anarchy of inter film criticism since its origins. net amateurs and the lack of authorita of tive critics, many journalists and acade Mattias Frey is Senior Lecturer in Film at film mics claim that in the digital age, cultural the University of Kent, author of Postwall commentary has become dumbed down German Cinema: History, Film History, C and fragmented into niche markets. and Cinephilia, coeditor of Cine-Ethics: riti Arguing against these claims, this book Ethical Dimensions of Film Theory, Prac- C examines the history of film critical dis tice, and Spectatorship, and editor of the ism course in France, Germany, the United journal Film Studies. AUP.nl 9789089647177 9789089648167 The Permanent Crisis of Film Criticism Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical founda- tions of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory. -

Documentaries Feature Length

feature length documentaries LIBRARY best of fests OSCAR NOMINEE LOCARNO HALE COUNTY THIS FOR BEST DOC EACH AND EVERY CÉSAR NOMINEE MORNING, THIS EVENING SUNDANCE MOMENT FOR BEST DOC by RaMell Ross by Nicolas Philibert Composed of intimate and unencumbered moments of Each And Every Moment follows young women and men in people in a community, this film is constructed in a form nurshing school with the ups and downs of an apprenticeship that allows the viewer an emotive impression of the Historic that confronts them with the life in all its complexities. South - trumpeting the beauty of life and consequences of the social construction of race, while simultaneously existing as a testament to dreaming - despite the odds. By the same director: Easter Snap - 14' / 2018 Idiom Film - Louverture Films / USA / 76' / 2018 Archipel 35 - Longride / France - Japan / 105' / 2018 CANNES SPECIAL SCREENING CANNES DEAD SOULS TORONTO HISSEIN HABRÉ, TORONTO by Wang Bing A CHADIAN TRAGEDY NYFF In Gansu Province, northwest China, lie the remains of by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun countless prisoners abandoned in the Gobi Desert sixty years ago. Designated as "ultra-rightists" in the Communist Party's In 2013, former Chadian dictator Hissein Habré's arrest in Anti-Rightist campaign of 1957, they starved to death in the Senegal marked the end of a long combat for the survivors of Jiabiangou and Mingshui reeducation camps. The film invites his regime. Accompanied by the Chairman of the Association us to meet the survivors of the camps to find out firsthand of the Victims of the Hissein Habré Regime, Mahamat Saleh who these persons were, the hardships they were forced to Haroun goes to meet those who survived this tragedy and endure and what became their destiny. -

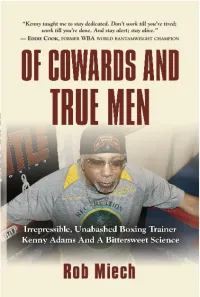

Of Cowards and True Men Order the Complete Book From

Kenny Adams survived on profanity and pugilism, turning Fort Hood into the premier military boxing outfit and coaching the controversial 1988 U.S. Olympic boxing team in South Korea. Twenty-six of his pros have won world-title belts. His amateur and professional successes are nonpareil. Here is the unapologetic and unflinching life of an American fable, and the crude, raw, and vulgar world in which he has flourished. Of Cowards and True Men Order the complete book from Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/8941.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Enjoy your free excerpt below! Of Cowards and True Men Rob Miech Copyright © 2015 Rob Miech ISBN: 978-1-63490-907-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., Bradenton, Florida, U.S.A. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2015 First Edition I URINE SPRAYS ALL over the black canvas. A fully loaded Italian Galesi-Brescia 6.35 pearl-handled .25-caliber pistol tumbles onto the floor of the boxing ring. Just another day in the office for Kenny Adams. Enter the accomplished trainer’s domain and expect anything. “With Kenny, you never know,” says a longtime colleague who was there the day of Kenny’s twin chagrins. First off, there’s the favorite word. Four perfectly balanced syllables, the sweet matronly beginning hammered by the sour, vulgar punctuation. -

Untersucht an Einem Film Von Frederick Wiseman

Abschlussarbeit zur Erlangung der Magistra Artium im Fachbereich Theater-, Film und Medienwissenschaft der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main Institut für Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Repräsentationsformen des Direct Cinema – untersucht an einem Film von Frederick Wiseman 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Heide Schlüpmann 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Burkhardt Lindner vorgelegt von: Esther Zeschky aus: Schotten Einreichungsdatum: 09. 07. 2002 1 Antje, für alles. Thank You! 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung 4 2. Vom non-fiction-Film zur documentary Frühe Formen des Dokumentarfilms 8 3. Das amerikanische Direct Cinema der 60er Jahre 17 3.1 Einflüsse auf das Direct Cinema 24 3.2 Ästhetik, Authentizität und Objektivität im Direct Cinema 41 3.3 Die Drew Associates 45 3.3.1 Die Erzählstruktur der Drew-Filme 52 3.3.2 Leacocks und Pennebakers Trennung von den Drew Associates und andere Filmemacher des Direct Cinema 55 4. Der Dokumentarfilmer Frederick Wiseman 57 4.1 Frederick Wisemans Vorgehensweise 64 4.2 Analyse des Films High School (1968) 69 5. Schlussbemerkung 83 6. Literaturverzeichnis 89 7. Anhang 85 Segmentierung des Films High School (1968) 96 Abbildungen 101 Frederick Wiseman’s Documentary Films 102 3 1. Einleitung Every film is a documentary. Even the most whimsical of fictions gives evidence of the culture that produced it and reproduces the likenesses of the people who perform within it. In fact, we could say that there are two kinds of film: (1) documentaries of wish-fulfillment and (2) documentaries of social representation. Each type tells a story, but the stories, or narratives, are of different sorts.1 Wie Bill Nichols in obigem Zitat treffend zum Ausdruck bringt, gibt es keine scharfe Trennungslinie zwischen Dokumentarfilm und Spielfilm.