Dynamics and Impacts of Peasants' Movement In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People of Ghazni

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs/ Province: Zabul April 13, 2009 Governor: Mohammad Ashraf Nasseri Provincial Police Chief: Colonel Mohammed Yaqoub Population Estimate: Urban: 9,200 Rural: 239,9001 249,100 Area in Square Kilometers: 17,343 Capital: Qalat (formerly known as Qalat-i Ghilzai) Names of Districts: Arghandab, Baghar, Day Chopan, Jaldak, Kaker, Mizan, Now Bahar, Qalat, Shah Joy, Shamulza’i, Shinkay Composition of Population: Ethnic Groups: Religions: Tribal Groups: Tokhi & Hotaki Majority Pashtun Predominately Sunni Ghilzais, Noorzai &Panjpai Islam Durranis Occupation of Population Major: Agriculture (including opium), labor, Minor: Trade, manufacturing, animal husbandry smuggling Crops/Farming/ Poppy, wheat, maize, barley, almonds, Sheep, goat, cow, camel, donkey Livestock:2 grapes, apricots, potato, watermelon, cumin Language: Overwhelmingly Pashtu, although some Dari can be found, mostly as a second language Literacy Rate Total: 1% (1% male, a few younger females)3 Number of Educational Primary & Secondary: 168 (98% all Colleges/Universities: None, although Institutions: 80 male) 35272 student (99% male), some training centers do exist for 866 teachers (97% male) vocational skills Number of Security Incidents, January: 3 May: 6 September: 7 2007:774 February: 4 June: 8 October: 7 March: 3 July: 8 November: 10 April: 11 August: 5 December: 5 Poppy (Opium) Cultivation: 2006: 3,210ha 2007: 1,611ha NGOs Active in Province: Ibn Sina, Vara, ADA, Red Crescent, CADG Total PRT Projects: 40 Other Aid Projects: 573 Planned Cost: $8,283,665 Planned Cost: $19,983,250 Total Spent: $2,997,860 Total Spent: $1,880,920 Transportation: 1 Airstrip in Primary Roads: The ring road from Ghazni to Kandahar passes through Qalat and Qalat “PRT Air” – 2 flights Shah Joy. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Aamir, A. (2015a, June 27). Interview with Syed Fazl-e-Haider: Fully operational Gwadar Port under Chinese control upsets key regional players. The Balochistan Point. Accessed February 7, 2019, from http://thebalochistanpoint.com/interview-fully-operational-gwadar-port-under- chinese-control-upsets-key-regional-players/ Aamir, A. (2015b, February 7). Pak-China Economic Corridor. Pakistan Today. Aamir, A. (2017, December 31). The Baloch’s concerns. The News International. Aamir, A. (2018a, August 17). ISIS threatens China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. China-US Focus. Accessed February 7, 2019, from https://www.chinausfocus.com/peace-security/isis-threatens- china-pakistan-economic-corridor Aamir, A. (2018b, July 25). Religious violence jeopardises China’s investment in Pakistan. Financial Times. Abbas, Z. (2000, November 17). Pakistan faces brain drain. BBC. Abbas, H. (2007, March 29). Transforming Pakistan’s frontier corps. Terrorism Monitor, 5(6). Abbas, H. (2011, February). Reforming Pakistan’s police and law enforcement infrastructure is it too flawed to fix? (USIP Special Report, No. 266). Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace (USIP). Abbas, N., & Rasmussen, S. E. (2017, November 27). Pakistani law minister quits after weeks of anti-blasphemy protests. The Guardian. Abbasi, N. M. (2009). The EU and Democracy building in Pakistan. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Accessed February 7, 2019, from https:// www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/chapters/the-role-of-the-european-union-in-democ racy-building/eu-democracy-building-discussion-paper-29.pdf Abbasi, A. (2017, April 13). CPEC sect without project director, key specialists. The News International. Abbasi, S. K. (2018, May 24). -

Floristic List and Their Ecological Characteristics, of Plants at Village

Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 2017; 5(5): 295-299 ISSN (E): 2320-3862 ISSN (P): 2394-0530 Floristic list and their ecological characteristics, NAAS Rating 2017: 3.53 JMPS 2017; 5(5): 295-299 of plants at village Sherpao District Charsadda, © 2017 JMPS Received: 16-07-2017 KP-Pakistan Accepted: 17-08-2017 Sajjad Ali Department of Botany, Bacha Sajjad Ali, Muhammad Shuaib, Hazart Ali, Sami Ullah, Kashif Ali, Khan University Charsadda, Saddam Hussain, Nazim Hassan, Umar Zeb, Wisal Muhammad Khan and Pakistan Fida Hussain Muhammad Shuaib School of Ecology and Environmental Science, Yunnan Abstract University, NO.2 North Cuihu Floral diversity of village Sherpao district Charsadda comprised a total of 104 plant species belonging to road, Kunming, Yunnan, PR. 46 families and 95 genera. The leading families were Fabaceae, Asteraceae and Poaceae contributed by 8 China species each (7.69%) followed by Solanaceae contributed by 7 species (6.73%), while Euphorbiaceae and Hazart Ali Lamiaceae contributed by 5 species each (4.80%) followed by Polygonaceae contributed by 4 species Department of Botany, Bacha (3.84%). Amaranthaceae, Amaryllidaceae, Boraginaceae, Malvaceae, Moraceae, Myrtaceae and Khan University Charsadda, Rutaceae contribute by 3 species each (2.88%) which is followed by Apiaceae, Cannabaceae, Pakistan Caryophyllaceae, Nyctaginaceae, Plantaginaceae, Mimosaceae and Ranunculaceae contributed 2 species Sami Ullah each (1.92%). Rest of 24 families contributed by 1 species each (0.96%). The most dominant life form Department of Botany, University was therophytes having 35 species (33.65%) followed by chamaephytehaving 17 species (16.34%) of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan followed by nanophanerophyte contributed by 15 species. -

Conflict Between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict

Conflict between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict Conflict between India and Pakistan Peter Lyon Conflict in Afghanistan Ludwig W. Adamec and Frank A. Clements Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia John B. Allcock, Marko Milivojevic, and John J. Horton, editors Conflict in Korea James E. Hoare and Susan Pares Conflict in Northern Ireland Sydney Elliott and W. D. Flackes Conflict between India and Pakistan An Encyclopedia Peter Lyon Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright 2008 by ABC-CLIO, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lyon, Peter, 1934– Conflict between India and Pakistan : an encyclopedia / Peter Lyon. p. cm. — (Roots of modern conflict) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57607-712-2 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-57607-713-9 (ebook) 1. India—Foreign relations—Pakistan—Encyclopedias. 2. Pakistan-Foreign relations— India—Encyclopedias. 3. India—Politics and government—Encyclopedias. 4. Pakistan— Politics and government—Encyclopedias. I. Title. DS450.P18L86 2008 954.04-dc22 2008022193 12 11 10 9 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Production Editor: Anna A. Moore Production Manager: Don Schmidt Media Editor: Jason Kniser Media Resources Manager: Caroline Price File Management Coordinator: Paula Gerard This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. -

Ancient Universities in India

Ancient Universities in India Ancient alanda University Nalanda is an ancient center of higher learning in Bihar, India from 427 to 1197. Nalanda was established in the 5th century AD in Bihar, India. Founded in 427 in northeastern India, not far from what is today the southern border of Nepal, it survived until 1197. It was devoted to Buddhist studies, but it also trained students in fine arts, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, politics and the art of war. The center had eight separate compounds, 10 temples, meditation halls, classrooms, lakes and parks. It had a nine-story library where monks meticulously copied books and documents so that individual scholars could have their own collections. It had dormitories for students, perhaps a first for an educational institution, housing 10,000 students in the university’s heyday and providing accommodations for 2,000 professors. Nalanda University attracted pupils and scholars from Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Indonesia, Persia and Turkey. A half hour bus ride from Rajgir is Nalanda, the site of the world's first University. Although the site was a pilgrimage destination from the 1st Century A.D., it has a link with the Buddha as he often came here and two of his chief disciples, Sariputra and Moggallana, came from this area. The large stupa is known as Sariputra's Stupa, marking the spot not only where his relics are entombed, but where he was supposedly born. The site has a number of small monasteries where the monks lived and studied and many of them were rebuilt over the centuries. We were told that one of the cells belonged to Naropa, who was instrumental in bringing Buddism to Tibet, along with such Nalanda luminaries as Shantirakshita and Padmasambhava. -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Peshawar Museum Is a Rich Repository of the Unique Art Pieces of Gandhara Art in Stone, Stucco, Terracotta and Bronze

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Peshawar Museum is a rich repository of the unique art pieces of Gandhara Art in stone, stucco, terracotta and bronze. Among these relics, the Buddhist Stone Sculptures are the most extensive and the amazing ones to attract the attention of scholars and researchers. Thus, research was carried out on the Gandharan Stone Sculptures of the Peshawar Museum under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Ihsan Ali, the then Director of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of NWFP, currently Vice Chancellor Hazara University and Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar. The Research team headed by the authors included Messrs. Syed Ayaz Ali Shah, Muhammad Ashfaq, Abdul Hameed Chitrali, Muhammad Zahir, Asad Raza, Shahid Khan, Muhammad Imran Khan, Asad Ali, Muhammad Haroon, Ubaidullah Afghani, Kaleem Jan, Adnan Ahmad, Farhana Waqar, Saima Afzal, Farkhanda Saeed and Ihsanullah Jan, who contributed directly or indirectly to the project. The hard working team with its coordinated efforts usefully assisted for completion of this research project and deserves admiration for their active collaboration during the period. It is great privilege to offer our sincere thanks to the staff of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums Govt. of NWFP, for their outright support, in the execution of this research conducted during 2002-06. Particular mention is made here of Mr. Saleh Muhammad Khan, the then Curator of the Peshawar Museum, currently Director of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of NWFP. The pioneering and relevant guidelines offered by the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of NWFP deserve appreciation for their technical support and ensuring the availability of relevant art pieces. -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

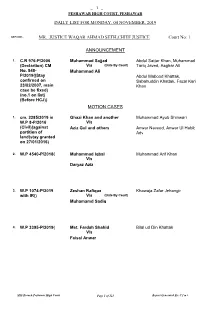

Single Bench List for 04-11-2019

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 04 NOVEMBER, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 ANNOUNCEMENT 1. C.R 976-P/2006 Muhammad Sajjad Abdul Sattar Khan, Muhammad (Declartion) CM V/s (Date By Court) Tariq Javed, Asghar Ali No. 848- Muhammad Ali P/2019((Stay Abdul Mabood Khattak, confirned on Sabahuddin Khattak, Fazal Karim 23/02/2007, main Khan case be fixed) (no.1 on list) (Before HCJ)) MOTION CASES 1. cm. 2285/2019 in Ghazi Khan and another Muhammad Ayub Shinwari W.P 8-P/2016 V/s (Civil)(against Aziz Gul and others Anwar Naveed, Anwar Ul Habib partition of Adv land(stay granted on 27/01/2016) 2. W.P 4540-P/2018() Muhammad Iqbal Muhammad Arif Khan V/s Daryaz Aziz 3. W.P 1074-P/2019 Zeshan Rafique Khawaja Zafar Jehangir with IR() V/s (Date By Court) Muhamamd Sadiq 4. W.P 3395-P/2019() Mst. Fardah Shahid Bilal ud Din Khattak V/s Faisal Anwar MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 121 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 04 NOVEMBER, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 5. W.P 4300-P/2019() Afzal Imran Ali Mohmand V/s Mst. Rashida i W.P 4716/2019 Mst Rashida Abid Ayub V/s Afzal 6. Cr.M(BCA) 3065- The State Waqas Khan Chamkani P/2019() V/s Noor Dad Khan 7. Cr.M(BCA) 3100- Muhammad Yousaf Syed Abdul Fayaz P/2019() V/s Abdullah Cr Appeal Branch AG Office 8. -

The Parinirvana Cycle and the Theory of Multivalence: a Study Of

THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYCLE AND THE THEORY OF MULTIVALENCE: A STUDY OF GANDHĀRAN BUDDHIST NARRATIVE RELIEFS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2017 By Emily Hebert Thesis Committee: Paul Lavy, Chairperson Kate Lingley Jesse Knutson TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1. BUDDHISM IN GREATER GANDHĀRA ........................................................... 9 Geography of Buddhism in Greater Gandhāra ....................................................................... 10 Buddhist Textual Traditions in Greater Gandhāra .................................................................. 12 Historical Periods of Buddhism in Greater Gandhāra ........................................................... 19 CHAPTER 2. GANDHĀRAN STŪPAS AND NARRATIVE ART ............................................. 28 Gandhāran Stūpas and Narrative Art: Architectural Context ................................................. 35 CHAPTER 3. THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYLCE OF NARRATIVE RELIEFS ................................ 39 CHAPTER 4 .THE THEORY OF MULTIVALENCE AND THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYCLE ...... 44 CHAPTER 5. NARRATIVE RELIEF PANELS FROM THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYCLE ............ 58 Episode -

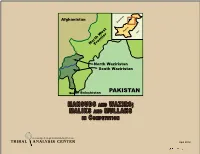

Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition

Afghanistan FGHANISTAN A PAKISTAN INIDA NorthFrontier West North Waziristan South Waziristan Balochistan PAKISTAN MAHSUDS AND WAZIRS; MALIKS AND MULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER April 2012 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition M AHSUDS AND W AZIRS ; M ALIKS AND M ULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition No patchwork scheme—and all our present recent schemes...are mere patchwork— will settle the Waziristan problem. Not until the military steam-roller has passed over the country from end to end, will there be peace. But I do not want to be the person to start that machine. Lord Curzon, Britain’s viceroy of India The great drawback to progress in Afghanistan has been those men who, under the pretense of religion, have taught things which were entirely contrary to the teachings of Mohammad, and that, being the false leaders of the religion. The sooner they are got rid of, the better. Amir Abd al-Rahman (Kabul’s Iron Amir) The Pashtun tribes have individual “personality” characteristics and this is a factor more commonly seen within the independent tribes – and their sub-tribes – than in the large tribal “confederations” located in southern Afghanistan, the Durranis and Ghilzai tribes that have developed in- termarried leadership clans and have more in common than those unaffiliated, independent tribes. Isolated and surrounded by larger, and probably later arriving migrating Pashtun tribes and restricted to poorer land, the Mahsud tribe of the Wazirs evolved into a nearly unique “tribal culture.” For context, it is useful to review the overarching genealogy of the Pashtuns. -

Prospects of Civilian Rule in Pakistan

Rtqurgevu"qh"Ekxknkcp"Twng"kp"Rcmkuvcp" Attar Rabbani ∗ " Cduvtcev" In direct contravention to founding fathers’ envision, Pakistan was ruled, by the military for much of its existence. Whenever civilian rule manage to come about has been compromised at best and distorted at the worst, at the behest of the men in Khaki. The Pakistani military is often held responsible for and accused of undermining institutional growth. Moreover political representatives when in power did not deliver on ‘stability’ and ‘development’ front due to ideological and structural inadequacies, giving an excuse for military to intervene. Besides the power relations that Pakistan inherited – feudal dominance – continued unabated even after independence, establishing its iron hold onto state institutions including that of the military. In fact, social composition of feudal elites did not alter all these decades, pushing majority of people out of the corridors of power. Even presently unraveling social, economic and political upheavals, it seems not powerful enough to rupture and debase elites. Given these socio- political and economic realities prevalent in Pakistan as to what are the prospects of civilian rule in the country? This paper explores answers to that question in a context of renewed optimism that is sweeping the country at present - because a democratically elected government is completing its full five year term (2008-2013) - a rare political achievement; and argues that civil-military relations shall continue to radiate disappointment in view of ever growing role of security establishment on account of extremely volatile neighborhood and violent politics within. " " Mg{yqtfu : Military rule, Civilian rule, Institutional development, democracy, Pakistan " " Kpvtqfwevkqp" Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the Father of the Nation of Pakistan was a peculiar political breed of the time, who in his initial career championed social causes of united India, democratic living and secular politics. -

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan)

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 The Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South is based on a network of partnerships with research institutions in the South and East, focusing on the analysis and mitigation of syndromes of global change and globalisation. Its sub-group named IP6 focuses on institutional change and livelihood strategies: State policies as well as other regional and international institutions – which are exposed to and embedded in national economies and processes of globalisation and global change – have an impact on local people's livelihood practices and strategies as well as on institutions developed by the people themselves. On the other hand, these institutionally shaped livelihood activities have an impact on livelihood outcomes and the sustainability of resource use. Understanding how the micro- and macro-levels of this institutional context interact is of vital importance for developing sustainable local natural resource management as well as supporting local livelihoods. For an update of IP6 activities see http://www.nccr-north-south.unibe.ch (>Individual Projects > IP6) The IP6 Working Paper Series presents preliminary research emerging from IP6 for discussion and critical comment. Author Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. Village & Post Office Hazara, Tahsil Kabal, Swat–19201, Pakistan e-mail: [email protected] Distribution A Downloadable pdf version is availale at www.nccr- north-south.unibe.ch (-> publications) Cover Photo The Swat Valley with Mingawara, and Upper Swat in the background (photo Urs Geiser) All rights reserved with the author.