M Mackie Dissertation Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: an American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties Elizabeth C

Student Publications Student Scholarship 3-2013 Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: An American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties Elizabeth C. Williams Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Nonfiction Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Williams, Elizabeth C., "Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: An American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties" (2013). Student Publications. 61. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/61 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 61 This open access creative writing is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: An American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties Abstract This paper is a collection of my personal experiences with the Welsh culture, both as a celebration of heritage in America and as a way of life in Wales. Using my family’s ancestral link to Wales as a narrative base, I trace the connections between Wales and America over the past century and look closely at how those ties have changed over time. The piece focuses on five location-based experiences—two in America and three in Wales—that each changed the way I interpret Welsh culture as a fifth-generation Welsh-American. -

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document cannot be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. 1 Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in established music trade publications. Please provide DotMusic with evidence that such criteria is met at [email protected] if you would like your artist name of brand name to be included in the DotMusic GPML. GLOBALLY PROTECTED MARKS LIST (GPML) - MUSIC ARTISTS DOTMUSIC (.MUSIC) ? and the Mysterians 10 Years 10,000 Maniacs © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document 10cc can not be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part 12 Stones without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. Visit 13th Floor Elevators www.music.us 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Unlimited Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. 3 Doors Down Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in 30 Seconds to Mars established music trade publications. Please -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Musicolinguistics: New Methodologies for Integrating Musical and Linguistic Data Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/59p4d43d Author Sleeper, Morgan Thomas Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Musicolinguistics: New Methodologies for Integrating Musical and Linguistic Data A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Morgan Thomas Sleeper Committee in charge: Professor Matthew Gordon, Chair Professor Eric Campbell Professor Timothy Cooley Professor Marianne Mithun June 2018 The dissertation of Morgan Thomas Sleeper is approved. ______________________________________________ Eric Campbell ______________________________________________ Timothy Cooley ______________________________________________ Marianne Mithun ______________________________________________ Matthew Gordon, Committee Chair June 2018 Musicolinguistics: New Methodologies for Integrating Musical and Linguistic Data Copyright © 2018 by Morgan Thomas Sleeper iii For Nina iv Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been possible without the faculty, staff, and students of UCSB Linguistics, and I am so grateful to have gotten to know, learn from, and work with them during my time in Santa Barbara. I'd especially like to thank my dissertation committee, Matt Gordon, Marianne Mithun, Eric Campbell, and Tim Cooley. Their guidance, insight, and presence were instrumental in this work, but also throughout my entire graduate school experience: Matt for being the best advisor I could ask for; Marianne for all her support and positivity; Eric for his thoughtful comments and inspirational kindness; and Tim for making me feel so warmly welcome as a linguistics student in ethnomusicology. -

201611 Indie 006.Pdf

ADRABLE ADRABLE ALICE IN CHAINS ALICE IN CHAINS ARAB STRAP Against Perfection Fake Facelift Alice In Chains Elephant Shoe ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1993年 CREATION 【CRELP138】 1994年 CREATION 【CRELP165】 1990年 CBS 【467201-1】 1995年 COLUMBIA 【C267248】 1999年 GO! BEAT 【5478051】 UK ORIGINAL LP UK ORIGINAL LP+7" UK ORIGINAL LP US ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL LP INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE 初回7inch付 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥4,000 価格 ¥3,000 価格 ¥10,000 価格 ¥7,000 価格 ¥4,000 BEASTIE BOYS BEASTIE BOYS BECK BECK BECK Anthology: The Sounds Of Science To The 5 Boroughs Midnite Vultures Information - Deluxe Vinyl Package Odelay ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 2000年 CAPITOL 【724352294015】 2004年 CAPITOL 【724358457117】 2000年 BONG LOAD 【BL46】 2008年 ARTIST IN RESIDENCE 【BTI0001】 2008年 ORIGINAL GROUP 【ORG010】 US ORIGINAL 4LP EU ORIGINAL 2LP US ORIGINAL LP US ORIGINAL 4LP US REISSUE 4LP BOOKLET INNER SLEEVE LTD.3000 LTD.6000 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥10,000 価格 ¥4,000 価格 ¥10,000 価格 ¥20,000 価格 ¥10,000 BELLE & SEBASTIAN BEN KWELLER BEULAH BEULAH BLACK CROWES Tigermilk Sha Sha When Your Heartstrings Break The Coast Is Never Clear By Your Side ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1996年 ELECTRIC HONEY 【EHRLP005】 2002年 679 【0927477201】 1999年 SUGAR FREE 【SF012LP】 2001年 VELOCETTE 【9430001】 1999年 COLUMBIA 【COL4916991】 UK ORIGINAL LP UK ORIGINAL LP US ORIGINAL LP US ORIGINAL LP EU ORIGINAL LP INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE CLEAR VINYL 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥25,000 価格 ¥7,000 価格 ¥3,500 価格 ¥3,500 価格 ¥10,000 BLACK CROWES BLACK CROWES BLACK CROWES BLIND MELON BLUR Lions Before The Frost.. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Praxis Makes Perfect

Praxis Makes Perfect NATIONaL tHEATRE WaLES & NeON NeON NationaL Theatre WaLes & Neon Neon Praxis Makes Perfect Conceived aNd PerfOrMed by Gruff Rhys aNd Boom biP LooseLy based on tHe book seNiOr service by carlo feLtriNelli B #Ntwneonneon Neon Neon bryaN Hollon ‘Boom biP’ Gruff Rhys In 2007, Gruff Rhys and Boom Bip launched Bryan is originally from Cincinnati, Ohio Gruff Rhys is a Welsh musician, performing Cerddor Cymreig yw Gruff Rhys, sy’n perfformio the electro-pop collaboration Neon Neon. and is currently based in Los Angeles. After solo and with several bands. He was born ar ei ben ei hun a gyda sawl band. Cafodd Their first album, Stainless Style, was released starting his career as a DJ – presenting on in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire and grew ei eni yn Hwlffordd, Sir Benfro ac fe’i magwyd in 2008 and is a concept album based on the the radio and hosting club nights – he met up in Bethesda, Gwynedd in north Wales. Gruff ym Methesda, Gwynedd yng ngogledd Cymru. life of John DeLorean, founder of the DeLorean and collaborated with other producers and first found his voice as the front man of the Daeth Gruff i’r amlwg fel prif ganwr Ffa Coffi Motor Company. The album included high-profile artists including rapper Doseone. Boom Bip band Ffa Coffi Pawb (Everyone’s Coffee Beans), Pawb (Everyone’s Coffee Beans), oedd wedi’u guest appearances from the likes of The Strokes’ and Doseone’s collaborative album Circle who were signed to Ankst and became one cofrestru ag Ankstmusik a ddaethant yn un Fab Moretti, Har Mar Superstar, Cate Le Bon was noted by John Peel in the UK, and the of the leading bands on the Welsh language o brif fandiau’r byd cerddoriaeth yng Nghymru. -

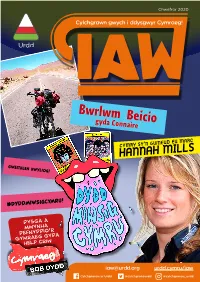

Bwrlwm Beicio Gyda Connaire

Chwefror 2020 Cylchgrawn gwych i ddysgwyr Cymraeg! Bwrlwm Beicio gyda Connaire Gweithlen hwyliog! #DyddMiwsigCymru! Dysga a mwynha defnyddio’r Gymraeg gyda help criw [email protected] urdd.cymru/iaw Cylchgronau yr Urdd @cylchgronaurdd @cylchgronau_urdd Geirfa: hufen iâ - ice cream Mis Chwefror hapus i chi a doubt dyddiadur - diary teledu - tv awyr agored - outdoors ddarllenwyr IAW! Mae dau grawnfwyd - cereal anhygoel - incredible siwgr - sugar yn ddiweddarach - later on nawr ac yn y man - now and berson ifanc o Ysgol Gyfun ar y cyfan - on the whole y lolfa - the living room again Trefynwy wedi ysgrifennu ysblennydd - splendid amser egwyl - break time cysgu - to sleep blaenwr - forward (rugby dyddiaduron yn trafod eu ffrwythau - fruit mefus - strawberry ysgytlaeth - milkshake ieithoedd - languages position) hwythnosau. Hefyd, mae adio a lluosi - add and a bod yn onest - to be honest fodd bynnag - however pobl ifanc o Ysgol Uwchradd multiply a dweud y gwir - to tell the ar y llaw arall - on the other Caerdydd wedi mynegi eu cerddoriaeth - music truth hand digrif - funny tywysogion - princes coginio - cooking barn am eu hoff bethau a oren - orange tŵr - tower rhaglenni. sur - sour beth bynnag - whatever anghytuno - to disagree dychrynllyd - frightful pos - puzzle soffistigedig - sophisticated Beth wyt ti’n gwneud yn blasus - tasty straeon - stories gwastraff amser - a waste of ystod yr wythnos? Beth yw dy ardderchog - excellent llawn dychymyg - full of time uwd - porridge imagination anghredadwy - unbelievable farn di am raglenni Cymraeg? mêl - honey arlunio - to draw enillon ni - we won brechdan - sandwich operâu sebon - soap operas Anfona lythyr atom ni at cyw iâr - chicken yn enwedig - especially natur - nature [email protected] ymolchais - I washed cig moch - bacon actio - acting ymlaciol - relaxing cur pen - headache i ddweud y gwir - to tell the cinio rhost - roast dinner diodydd pefriog - fizzy drinks truth llysiau - vegetables yn gynnar - early cig - meat heb os nac oni bai - without fodd bynnag - however Annwyl Iaw, hefyd. -

Building New Business Strategies for the Music Industry in Wales

Knowledge Exploitation Capacity Development Academic Expertise for Business Building New Business Strategies for the Music Industry in Wales Final report School of Music BANGOR UNIVERSITY This study is funded by an Academia for Business (A4B) grant, which is managed by the Welsh Assembly Government’s Department for Economy and Transport, and is financed by the Welsh Assembly Government and the European Union. 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary.......................................................................................................5 The following conclusions are drawn from this study......................................................5 The following recommendations are made in this study ................................................6 Preface ..............................................................................................................................8 Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part 1: Background and Context: The Infrastructure of the WelshLanguage Popular Music Industry from 1965–c.2000......................................................... 12 1.1 Overview...................................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Record companies and sales .............................................................................................. 13 1.3 TV, radio and Welshlanguage music journalism .................................................... -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People.. -

Super Furry Animals

Super Furry Animals Super Furry Animals fue una de las primeras bandas post-alternativas que se atrevió a fusionar un número disparatado de géneros musicales que incluÃan el power pop, punk rock, tecno y rock progresivo. Desde un primer momento, destacaron y llamaron la atención de público y prensa, sobre todo por sus melodÃas contagiosas y su actitud irreverente. Formados en Cardiff en 1993 como una reagrupación de miembros de bandas distintas, los SFA empezaron como banda de tecno, aunque enseguida se dejaron cautivar por los sonidos neopsicodélicos y el pop progresivo. Tras dos años de conciertos, SFA firmaron su primer trabajo, un ep titulado Lianfairpwllgywgyllgoger Chwymdrobwlltysiliogoygoyocynygofod (In Space), escrito completamente en galés. Enseguida, firmaron otro ep, \"Moog Droog\", también en galés. Ambos ep\'s fueron producidos por Gorwel Owen. Para finales de 1995, Super Furry Animals habÃa conseguido una fuerte base de fans en Gales, lo que les catapultó al top 20 con \"Something for the weekend\", el single previo a su disco de debut. Su primer disco, \"Fuzzy Logic\", fue editado en 1996 y obtuvo excelentes crÃticas. Enseguida se convirtieron en una de las bandas lÃderes del movimiento musical galés de mediados de los 90 y una referencia de culto dentro de toda Gran Bretaña. A pesar de eso, fueron etiquetados de forasteros debido a su tendencia a cantar en su lengua nativa. A principios de 1997, se embarcaron en el tour que organiza el semanario musical británico NME para dar a conocer las nuevas bandas del momento. -

On Tour with Pastel Swansea’S Next Big Thing?

APRIL/MAY 2020 ISSUE#10 ON TOUR WITH PASTEL SWANSEA’S NEXT BIG THING? PLUS: JAMES WEAVER, SWANSEA UNIVERSITY, DAMIAN HARRIS, TOM EMLYN + MORE A message from the team at Soundboard Magazine: We had hoped to be in print for Issue #10. As you may know, we rely totally on advertising revenue to fi nance our production costs. This issue, the Coronavirus has meant that many of our advertisers have been forced to cancel events or close completely. We truly understand why some advertisers have felt it necessary to withdraw (temporarily we hope). This issue, therefore, will not be printed, but will be available as a PDF, which you are reading now, obviously. Please share it as much as you like, however you can. We have included all the adverts from advertisers who wanted to continue, however these have not been charged. The whole team (please DO read the credits on page 3) have worked hard over the last couple of months to bring you what we feel is our strongest issue yet. We hope you love it as much as we do. We are of course very disappointed not to be able to bring it to you in print. Please leave your comments on our Facebook Page, we love hearing from you. Stay well, and safe. We look forward to being back to normal as soon as circumstances allow. Graham, Sarah, Joel and all the writers at SBM. SOUNDBOARD | ISSUE #10 | APRIL & MAY 2020 INSIDE THE LOAD-IN . .4 NEWS . .5 OH PEDRO . .6 THE NEXT GENERATION – TRENCH . .7 THE BIG READ – JAMES WEAVER .