The Commission Is for an Article of Around 750 Words

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A DESIGN for LIFE As Recorded by Manic Street Preachers (From the 1996 Album "Everything Must Go")

A DESIGN FOR LIFE As recorded by Manic Street Preachers (from the 1996 Album "Everything Must Go") Transcribed by Matthew Ford Words by Nicky Wire Music by James Dean Bradfield & Sean Moore A Intro/Interlude P = 88 Cmaj7 1 12 V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V I 8 V V V V Gtr I let ring T 0 0 0 0 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 A 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 B 3 3 3 3 V V V V 12 j u j j u j j u j j u j I 8 Gtr II 20 20 20 20 T 20 20 20 20 A B B Verse Cmaj7 3 V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V I V V V V V let ring T 0 0 0 0 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 A 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 B 3 3 3 3 3 V V V V j u j j u j j u j j u j I 20 20 20 20 T 20 20 20 20 A B 1996 Sony Music Entertainment Ltd. Printed using TabView by Simone Tellini - http://www.tellini.org/mac/tabview/ A DESIGN FOR LIFE - Manic Street Preachers Page 2 of 11 Dm13 5 V V V V V V V V V V V V I V V V V V V V V V V V V let ring T 0 0 0 0 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 A 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 B 5 5 5 5 0 V V V V j u j j u j j u j j u j I 20 20 20 20 T 20 20 20 20 A B G7 7 V V V V I V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V let ring T 4 4 4 4 A 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 B 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 3 3 3 3 V V V V j u j j u j j u j j u j I 19 19 19 19 T 20 20 20 20 A B 1996 Sony Music Entertainment Ltd. -

The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell

Theosophical University Press Online Edition The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell Copyright © 1914 by Katherine Tingley; originally published at Point Loma, California. Electronic edition 2000 by Theosophical University Press ISBN 1- 55700-157-x. This edition may be downloaded for off-line viewing without charge. For ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in the electronic version of the text. To Katherine Tingley: Leader and Official Head of the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society, whose whole life has been devoted to the cause of Peace and Universal Brotherhood, this book is respectfully dedicated Contents Preface The Three Branches of the Bringing-in of it, namely: The Sovereignty of Annwn I. The Council of the Immortals II. The Hunt in Glyn Cuch III. The Slaying of Hafgan The Story of Pwyll and Rhianon, or The Book of the Three Trials The First Branch of it, called: The Coming of Rhianon Ren Ferch Hefeydd I. The Making-known of Gorsedd Arberth, and the Wonderful Riding of Rhianon II. The First of the Wedding-Feasts at the Court of Hefeydd, and the Coming of Gwawl ab Clud The Second Branch of it, namely: The Basket of Gwaeddfyd Newynog, and Gwaeddfyd Newynog Himself I. The Anger of Pendaran Dyfed, and the Putting of Firing in the Basket II. The Over-Eagerness of Ceredig Cwmteifi after Knowledge, and the Putting of Bulrush-Heads in the Basket III. The Circumspection of Pwyll Pen Annwn, and the Filling of the Basket at Last The First Branch of it again: III. -

Lisa Mansell Cardiff, Wales Mav 2007

FORM OF FIX: TRANSATLANTIC SONORITY IN THE MINORITY Lisa Mansell Cardiff, Wales Mav 2007 UMI Number: U584943 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584943 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 For 25 centuries Western knowledge has tried to look upon the world. It has failed to understand that the world is not for beholding. It is for hearing [...]. Now we must learn to judge a society by its noise. (Jacques Attali} DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature fof any degree. Signed r?rrr?rr..>......................................... (candidate) Date STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree o f ....................... (insert MCh, Mfo MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) (candidate) D ateSigned .. (candidate) DateSigned STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources aite acknowledged by explicit references. Signed ... ..................................... (candidate) Date ... V .T ../.^ . STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. -

Music Venue Trust Response to Music Industry in Wales Inquiry

Music Venue Trust response to Music Industry in Wales Inquiry 1. About Music Venue Trust Music Venue Trust is a registered charity which acts to protect, secure and improve Grassroots Music Venues in the UK. 1 Music Venue Trust is the representative body of the Music Venues Alliance 2, a network of over 500 Grassroots Music Venues in the UK. A full list of the 34 Music Venues Alliance Wales members is provided at Annex A. 2. Grassroots Music Venues in 2019 A. A nationally and internationally accepted definition of a Grassroots Music Venue (GMV) is provided at Annex B. This definition is now in wide usage, including by the UK, Scottish and Welsh Parliaments. 3 GMVs exhibit a specific set of social, cultural and economic attributes which are of special importance to communities, artists, audiences, and to the wider music industry. Across sixty years, this sector has played a vital research and nurturing role in the development of the careers of a succession of UK musicians, for example The Beatles (The Cavern, Liverpool) through The Clash (100 Club, London), The Undertones (The Casbah, Derry), Duran Duran (Rum Runner, Birmingham), Housemartins (Adelphi, Hull), Radiohead (Jericho Tavern, Oxford), Idlewild (Subway, Edinburgh). All three of the UK’s highest grossing live music attractions in 2017 (Adele, Ed Sheeran, Coldplay) commenced their careers with extensive touring in this circuit. 4 In Wales, GMVs have played a central role in kickstarting the careers of The Manic Street Preachers (TJs, Newport), Supper Furry Animals (Clwb Ifor Bach, Cardiff), The Joy Formidable, (Central Station, Wrexham), Gruff Rhys (Neuadd Ogwen, Bangor), Funeral For A Friend (Hobo’s Bridgend), Skindred (Sin City, Swansea). -

(Public Pack)Agenda Dogfen I/Ar Gyfer Pwyllgor

------------------------Pecyn dogfennau cyhoeddus ------------------------ Agenda - Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu Lleoliad: I gael rhagor o wybodaeth cysylltwch a: Ystafell Bwyllgora 2 - Y Senedd Steve George Dyddiad: Dydd Iau, 12 Gorffennaf 2018 Clerc y Pwyllgor Amser: 09.30 0300 200 6565 [email protected] ------ 1 Cyflwyniad, ymddiheuriadau, dirprwyon a datgan buddiannau 2 Ymchwiliad byr i ' Creu S4C ar gyfer y dyfodol: Adolygiad annibynnol gan Euryn Ogwen Williams': sesiwn dystiolaeth 1 (09:30 - 10:30) (Tudalennau 1 - 9) Euryn Ogwen Williams, Cadeirydd, Adolygiad Annibynnol o S4C Dogfennau: Creu S4C ar gyfer y dyfodol: Adolygiad annibynnol gan Euryn Ogwen Williams Ymateb Llywodraeth y DU 3 Cynyrchiadau ffilm a theledu mawr yng Nghymru: sesiwn dystiolaeth 16 (10:30 - 11:15) (Tudalennau 10 - 38) Dafydd Elis-Thomas AC, Gweinidog Diwylliant, Twristiaeth a Chwaraeon Mick McGuire, Cyfarwyddwr Busnes a'r Rhanbarthau Joedi Langley, Pennaeth y Sector Creadigol 4 Perthynas Llywodraeth Cymru â Pinewood: sesiwn dystiolaeth 2 (11:15 - 12:00) Dafydd Elis-Thomas AC, Gweinidog Diwylliant, Twristiaeth a Chwaraeon Mick McGuire, Cyfarwyddwr Busnes a'r Rhanbarthau Joedi Langley, Pennaeth y Sector Creadigol Dogfen: Adroddiad Swyddfa Archwilio Cymru: Perthynas Llywodraeth Cymru â Pinewood 5 Cynnig o dan Reol Sefydlog 17.42 i benderfynu gwahardd y cyhoedd o'r cyfarfod ar gyfer y busnes a ganlyn: Trafod y dystiolaeth (12:00 - 12:10) 6 Ystyried blaenraglen waith y pwyllgor (12:10 - 12:40) (Tudalennau 39 - 47) 7 Cyllid Celfyddydau nad -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

1 Review of Conservatoire and Performing-Arts Provision in Wales

Review of conservatoire and performing-arts provision in Wales Lord Murphy of Torfaen Submitted to the Cabinet Secretary for Education, Welsh Government November 2017 1 FOREWORD To the Cabinet Secretary for Education I am pleased to submit my Review of conservatoire and performing-arts provision in Wales. Task Your predecessor announced on 11 December 2015 that he had asked me to carry out an independent review. His Written Statement, which includes the terms of reference of the review, explained: "The aim of the Review is to ensure that Wales continues to benefit from high quality intensive performing arts courses which focus on practical, vocational performance. Such provision is crucial to the skills' needs of the creative industries and to the cultural life of Wales." The full terms of reference are set out in Appendix 1. I was asked to examine the current arrangements for supporting conservatoire and related provision in higher education in Wales and also to examine the role of the Higher Education Funding Council of Wales (HEFCW) in supporting this provision. I was also asked specifically for recommendations on the future funding of conservatoire and related provision in Wales, and for possible future curriculum developments to be identified. Method A general call was issued on the government website for submissions in response to the terms of reference. In addition, I wrote requesting submissions individually to the organisations most affected by the Review, the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama (RWCMD or the College), the University of South Wales (USW), HEFCW. I also wrote to the other universities in Wales and a range of organisations in the cultural and creative sector, including Arts Council Wales and the National Performing Companies. -

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

Cardiff Meetings & Conferences Guide

CARDIFF MEETINGS & CONFERENCES GUIDE www.meetincardiff.com WELCOME TO CARDIFF CONTENTS AN ATTRACTIVE CITY, A GREAT VENUE 02 Welcome to Cardiff That’s Cardiff – a city on the move We’ll help you find the right venue and 04 Essential Cardiff and rapidly becoming one of the UK’s we’ll take the hassle out of booking 08 Cardiff - a Top Convention City top destinations for conventions, hotels – all free of charge. All you need Meet in Cardiff conferences, business meetings. The to do is call or email us and one of our 11 city’s success has been recognised by conference organisers will get things 14 Make Your Event Different the British Meetings and Events Industry moving for you. Meanwhile, this guide 16 The Cardiff Collection survey, which shows that Cardiff is will give you a flavour of what’s on offer now the seventh most popular UK in Cardiff, the capital of Wales. 18 Cardiff’s Capital Appeal conference destination. 20 Small, Regular or Large 22 Why Choose Cardiff? 31 Incentives Galore 32 #MCCR 38 Programme Ideas 40 Tourist Information Centre 41 Ideas & Suggestions 43 Cardiff’s A to Z & Cardiff’s Top 10 CF10 T H E S L E A CARDIFF S I S T E N 2018 N E T S 2019 I A S DD E L CAERDY S CARDIFF CAERDYDD | meetincardiff.com | #MeetinCardiff E 4 H ROAD T 4UW RAIL ESSENTIAL INFORMATION AIR CARDIFF – THE CAPITAL OF WALES Aberdeen Location: Currency: E N T S S I E A South East Wales British Pound Sterling L WELCOME! A90 E S CROESO! Population: Phone Code: H 18 348,500 Country code 44, T CR M90 Area code: 029 20 EDINBURGH DF D GLASGOW M8 C D Language: Time Zone: A Y A68 R D M74 A7 English and Welsh Greenwich Mean Time D R I E Newcastle F F • C A (GMT + 1 in summertime) CONTACT US A69 BELFAST Contact: Twinned with: Meet in Cardiff team M6 Nantes – France, Stuttgart – Germany, Xiamen – A1 China, Hordaland – Norway, Lugansk – Ukraine Address: Isle of Man M62 Meet in Cardiff M62 Distance from London: DUBLIN The Courtyard – CY6 LIVERPOOL Approximately 2 hours by road or train. -

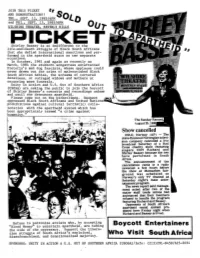

PICKET R, and DEMONSTRATION!! Sol

JOIN THIS PICKET r, AND DEMONSTRATION!! SOl.. THU., SEPT. 12, 1985/6PM 0 and FRI., SEPT. 13, 1985/6PM WILSHIRE THEATER, BEVERLY HILLS 00.,. PICKET Shirley Bassey is so indifferent to the life-and-death struggle of Black South Africans that she defied international sanctions and per formed in the apartheid state on two separate occasions. In October, 1981 and again as recently as March, 1984 the stubborn songstress entertained Pretoria's mad dog fascists, whose applause could never drown out the cries of malnourished Black South African babies, the screams of tortured detainees, or outraged widows and mothers at recurring mass funerals. Unity in Action and U.S. Out of Southern Africa (USOSA) are askin? the public to join the boycott of Shirley Bassey s concerts and recordings unless and until she denounces apartheid. Please come out on the picketlines. Respect oppressed Black South Africans and United Nations prohibitions against cultural (artistic) colla boration with" the apartheid system which has been appropriately termed "a crime against humani " OSLO, Norway (AP) - The state-financed Norwegian televi sion company cancelled a live broadcast Saturday of a Red Cross charity show featuring singers Cliff Richard and Shirley Bassey because the two have performed in South Africa. The annoWlcement of the cancellation came in a radio newscast a few hours before the show at Momarken fair ground was scheduled on Norway's only TV channel as Saturday night's main enter tainment program. The news report said manage ment acted after two of the major staff trade unions had annoWlced that their members refused to handle the prograIll featuring Richard and Bassey. -

Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: an American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties Elizabeth C

Student Publications Student Scholarship 3-2013 Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: An American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties Elizabeth C. Williams Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Nonfiction Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Williams, Elizabeth C., "Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: An American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties" (2013). Student Publications. 61. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/61 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 61 This open access creative writing is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pinning the Daffodil and Singing Proudly: An American's Search for Modern Meaning in Ancestral Ties Abstract This paper is a collection of my personal experiences with the Welsh culture, both as a celebration of heritage in America and as a way of life in Wales. Using my family’s ancestral link to Wales as a narrative base, I trace the connections between Wales and America over the past century and look closely at how those ties have changed over time. The piece focuses on five location-based experiences—two in America and three in Wales—that each changed the way I interpret Welsh culture as a fifth-generation Welsh-American. -

Chart - History Singles All Chart-Entries in the Top 100 Peak:1 Peak:1 Peak: 2 Germany / United Kindom / U S a Tom Jones

Chart - History Singles All chart-entries in the Top 100 Peak:1 Peak:1 Peak: 2 Germany / United Kindom / U S A Tom Jones No. of Titles Positions Sir Thomas John Woodward OBE (born 7 June Peak Tot. T10 #1 Tot. T10 #1 1940), known professionally as Tom Jones, is a 1 22 6 2 228 61 20 Welsh singer. His career has spanned six 1 44 20 3 431 92 9 decades, from his emergence as a vocalist in 2 28 5 -- 272 22 -- the mid-1960s with a string of top hits, regular touring, appearances in Las Vegas 1 49 23 5 931 175 29 (1967–2011), and career comebacks. ber_covers_singles Germany U K U S A Singles compiled by Volker Doerken Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 1 It's Not Unusual 02/1965 1 1 22 7204/1965 10 12 2 Once Upon A Time 05/1965 32 4 3 Little Lonely One 05/1965 42 9 4 What's New Pussycat 08/1965 11 10 06/1965 3 12 5 5 With These Hands 07/1965 13 11 08/1965 27 8 6 Thunderball 01/1966 35 4 12/1965 25 9 7 Promise Her Anything 02/1966 74 4 8 Once There Was A Time / Not Responsible 05/1966 18 9 9 Not Responsible 06/1966 58 6 10 This And That 08/1966 44 3 11 Green Green Grass Of Home 01/1967 6 22 1111/1966 1 7 22 13 12/1966 11 12 12 Detroit City 04/1967 35 4 02/1967 8 10 1 03/1967 27 8 13 Funny Familiar Forgotten Feelings 06/1967 38 2 04/1967 7 15 3 05/1967 49 6 14 I'll Never Fall In Love Again 10/1967 31 4 07/1967 2 25 9409/1967 6 23 15 Sixteen Tons 08/1967 68 4 16 I'm Coming Home 02/1968 39 4 11/1967 2 16 7 12/1967 57 5 17 Delilah 04/1968 1 13 31 2002/1968 2 19 8 03/1968 15 15 18 Help Yourself 08/1968 1 7 24 1507/1968 5 26 6 08/1968