1 Review of Conservatoire and Performing-Arts Provision in Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cardiff Meetings & Conferences Guide

CARDIFF MEETINGS & CONFERENCES GUIDE www.meetincardiff.com WELCOME TO CARDIFF CONTENTS AN ATTRACTIVE CITY, A GREAT VENUE 02 Welcome to Cardiff That’s Cardiff – a city on the move We’ll help you find the right venue and 04 Essential Cardiff and rapidly becoming one of the UK’s we’ll take the hassle out of booking 08 Cardiff - a Top Convention City top destinations for conventions, hotels – all free of charge. All you need Meet in Cardiff conferences, business meetings. The to do is call or email us and one of our 11 city’s success has been recognised by conference organisers will get things 14 Make Your Event Different the British Meetings and Events Industry moving for you. Meanwhile, this guide 16 The Cardiff Collection survey, which shows that Cardiff is will give you a flavour of what’s on offer now the seventh most popular UK in Cardiff, the capital of Wales. 18 Cardiff’s Capital Appeal conference destination. 20 Small, Regular or Large 22 Why Choose Cardiff? 31 Incentives Galore 32 #MCCR 38 Programme Ideas 40 Tourist Information Centre 41 Ideas & Suggestions 43 Cardiff’s A to Z & Cardiff’s Top 10 CF10 T H E S L E A CARDIFF S I S T E N 2018 N E T S 2019 I A S DD E L CAERDY S CARDIFF CAERDYDD | meetincardiff.com | #MeetinCardiff E 4 H ROAD T 4UW RAIL ESSENTIAL INFORMATION AIR CARDIFF – THE CAPITAL OF WALES Aberdeen Location: Currency: E N T S S I E A South East Wales British Pound Sterling L WELCOME! A90 E S CROESO! Population: Phone Code: H 18 348,500 Country code 44, T CR M90 Area code: 029 20 EDINBURGH DF D GLASGOW M8 C D Language: Time Zone: A Y A68 R D M74 A7 English and Welsh Greenwich Mean Time D R I E Newcastle F F • C A (GMT + 1 in summertime) CONTACT US A69 BELFAST Contact: Twinned with: Meet in Cardiff team M6 Nantes – France, Stuttgart – Germany, Xiamen – A1 China, Hordaland – Norway, Lugansk – Ukraine Address: Isle of Man M62 Meet in Cardiff M62 Distance from London: DUBLIN The Courtyard – CY6 LIVERPOOL Approximately 2 hours by road or train. -

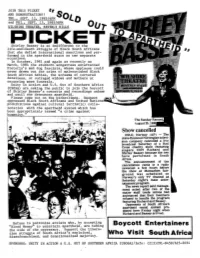

PICKET R, and DEMONSTRATION!! Sol

JOIN THIS PICKET r, AND DEMONSTRATION!! SOl.. THU., SEPT. 12, 1985/6PM 0 and FRI., SEPT. 13, 1985/6PM WILSHIRE THEATER, BEVERLY HILLS 00.,. PICKET Shirley Bassey is so indifferent to the life-and-death struggle of Black South Africans that she defied international sanctions and per formed in the apartheid state on two separate occasions. In October, 1981 and again as recently as March, 1984 the stubborn songstress entertained Pretoria's mad dog fascists, whose applause could never drown out the cries of malnourished Black South African babies, the screams of tortured detainees, or outraged widows and mothers at recurring mass funerals. Unity in Action and U.S. Out of Southern Africa (USOSA) are askin? the public to join the boycott of Shirley Bassey s concerts and recordings unless and until she denounces apartheid. Please come out on the picketlines. Respect oppressed Black South Africans and United Nations prohibitions against cultural (artistic) colla boration with" the apartheid system which has been appropriately termed "a crime against humani " OSLO, Norway (AP) - The state-financed Norwegian televi sion company cancelled a live broadcast Saturday of a Red Cross charity show featuring singers Cliff Richard and Shirley Bassey because the two have performed in South Africa. The annoWlcement of the cancellation came in a radio newscast a few hours before the show at Momarken fair ground was scheduled on Norway's only TV channel as Saturday night's main enter tainment program. The news report said manage ment acted after two of the major staff trade unions had annoWlced that their members refused to handle the prograIll featuring Richard and Bassey. -

Cardiff, Wales – the Places Where We Go Itinerary Day

CARDIFF, WALES – THE PLACES WHERE WE GO ITINERARY DAY ONE: The Heart of Cardiff Explore Cardiff City Center. This will help you get your bearings in the heart of Cardiff. Browse the unique shops within the Victorian Arcades. For modern shopping, you can explore the S t David’s Dewi Sant shopping center. Afternoon: Visit the N ational Museum Cardiff or stroll Cardiff via the Centenary Walk which runs 2.3 miles within Cardiff city center. This path passes through many of Cardiff’s landmarks and historic buildings. DAY TWO – Cardiff Castle and Afternoon Excursion Morning: Visit Cardiff Castle . One of Wales’ leading heritage attractions and a site of international significance. Located in the heart of the capital, Cardiff Castle’s walls and fairytale towers conceal 2,000 years of history. Arrive early and plan on at least 2 hours. Afternoon: Hop on a train to explore a local town – consider Llantwit Major or Penarth. We explored B arry Island, which offers seaside rides, food, and vistas of the Bristol Channel. DAY THREE – Castle Ruins Raglan Castle : Step back in time and explore the ruins of an old castle. Travel by train from Cardiff Central to Newport, where you’ll catch a bus at the Newport Bus Station-Friars Walks (careful to depart from the correct bus station). Have lunch in the town of Raglan at The Ship Inn before travelling back to Cardiff. You might find yourself waiting up to an hour for the bus ride back to the city. If time permits, hop off the bus on the way back to Cardiff to explore the ancient Roman village of Caerloen. -

Performing Borders

Radical Musicology Volume 1 (2006) ISSN 1751-7788 Beyond Borders: The Female Welsh Pop Voice Sarah Hill University of Southampton For all its reputation as a musical culture, the number of women pop stars to 1 have emerged from Wales can be counted charitably on two hands, with some fingers to spare. Wales is a small country, host to two rich linguistic cultures, each with its own musical heritage and traditions, yet very few musicians of either gender have crossed over from one tradition to the other. The rarity of a female singer making such a border crossing is marked, allowing for a delicate lineage to be traced across the decades, from the 1960s to the present, revealing certain commonalities of experience, acceptance, and reversion. With this in mind, I would like to draw a linguistic and cultural connection between two determinedly different Welsh women singers. In the 1960s, when women’s voices were the mainstays of Motown, the folk circuit and the Haight-Ashbury, in Wales only Mary Hopkin managed to shift from Welsh-language to Anglo-American pop; thirty years later, Cerys Matthews made the same journey. These two women bear certain similarities: they both come from South Wales, they are both singers whose first, or preferred, language is Welsh, and they both found their niche in the Anglo-American mainstream market. These two women faced the larger cultural problems of linguistic and musical border-crossings, but more importantly, they challenged the place of the female pop voice in Wales, and of the female Welsh pop voice in Anglo-America. -

WDAM Radio's History of the Animals

Listener’s Guide To “WDAM Radio’s History Of James Bond” You have security clearance to enjoy “WDAM Radio’s History Of James Bond.” Classified – until now, this is the most comprehensive top secret dossier of ditties from James Bond television and film productions ever assembled. WDAM Radio’s undercover record researchers have uncovered all the opening title themes, as well as “secondary songs” and various end title themes worth having. Our secret musicology agents also have gathered intelligence on virtually every known and verifiable* song that was submitted to and rejected by the various James Bond movie producers as proposed theme music. All of us at the station hope you will enjoy this musical license to thrill.** Rock on. Radio Dave *There is a significant amount of dubious data on Wikipedia and YouTube with respect to songs that were proposed, but not accepted, for various James Bond films. Using proprietary alga rhythms (a/k/a Radio Dave’s memory and WDAM Radio’s Groove Yard archives), as well as identifying obvious inconsistencies on several postings purporting to present such claims, we have revoked the license of such songs to be included in this collection. (For instance, two sites claim Elvis Presley songs that were included in two of his movies were originally proposed to the James Bond producers – not true.) **Watch for updates to this dossier as future James Bond films are issued, as well as additional “rejected songs” to existing films are identified and obtained via our ongoing overt and covert musicology surveillance activities. WDAM Radio's History Of James Bond # Film/Title (+ Year) Artist & (Composer) James Bond Chart Comments Position/ Year* 01 Casino Royale (1954) Barry Nelson 1954 Episode of Climax! Mystery Theater broadcast live on 10/21/1954 starring Barry Nelson. -

St David's Welsh Quiz

St David's Welsh Quiz 1 What is the Welsh name for St David? St Dewi 2 Where was Prince Charles invested as Prince of Wales? Caernarfon What was the name of the island on which the Americans dropped a hydrogen bomb on St Bikini Atoll 3 David's Day 1954? 4 In which year was the university of Wales founded: 1873, 1883, 1893 or 1903? 1893 5 Which flower is the emblem for Wales? Daffodil 6 What is the Welsh for Wales? Cymru 7 Which place in Wales was the setting for the TV series 'The Prisoner'? Port Merrion 8 In which city was Welsh songstress Shirley Bassey born? Cardiff 9 Which part of Wales did the Romans call Mona? Anglesey 10 Name the Welsh soldier who became famous after being badly burned in the Falklands war. Simon Weston 11 What three colours are used on the Welsh flag? Green, White & Red Born in Tonypandy on St David's Day who was the boxer who took Joe Louis the distance for Tommy Farr 12 his world crown? 13 Welshman Richard Jenkins was the real name of which famous actor? Richard Burton 14 What is the name of the small Welsh boat made of skins stretched over a frame? Coracle 15 What is the name of the annual festivals held to encourage the fine arts? Eisteddfod 16 What would your star sign be if you were born on St David's Day? Pisces 17 What is the sea weather area that lies to the south of Wales? Lundy 18 Which vegetable is an emblem of Wales? Leek 19 What is the name of the stretch of water which separates Anglesey from mainland Wales? Menai Strait 20 Which Welshman had a monster hit with the song 'Green Green Grass of Home'? -

Motorpoint Arena Cardiff Celebrates 25 Years of Making Memories

Motorpoint Arena Cardiff Celebrates 25 Years Of Making Memories (20 September 2018) - This month, Motorpoint Arena Cardiff celebrates 25 years since it opened its doors in the heart of Cardiff city centre. The Arena, owned and operated by Live Nation, has brought some of the world’s biggest names to Wales, from Beyoncé, P!NK and Elton John to Iron Maiden, Oasis and Panic! At The Disco, as well as hosting international events and conferences. Over the years, the venue has welcomed over 10 million fans through its doors. In the past 12 months, Live Nation has invested in a number of upgrades to ensure the venue continues to host memorable moments for years to come. Motorpoint Arena Cardiff’s rich history began with an opening gala on September 9 and 10, 1993 headlined by Dame Shirley Bassey at the then named Cardiff International Arena, followed by\ the official opening by Her Majesty The Queen on October 14, 1993. Since then, as well as the biggest names in music and comedy, the Arena has attracted events which have transformed the venue into an ice rink for skating spectaculars, boxing rings for international matches and even a motocross dirt track for high-speed racing. It has been a giant snooker hall, darts Arena, extravagant dinner hall and an all-in conference centre. It was a night to remember back in June 1995, when Diana, Princess of Wales, was in the Welsh capital to watch her friend Luciano Pavarotti perform a charity concert in her name. The Arena has hosted the Welsh BAFTAs, the closing gala dinner for the Rugby World Cup 1999 and even the FA Cup Sponsor Village whilst Wembley was closed. -

Building New Business Strategies for the Music Industry in Wales

Knowledge Exploitation Capacity Development Academic Expertise for Business Building New Business Strategies for the Music Industry in Wales Final report School of Music BANGOR UNIVERSITY This study is funded by an Academia for Business (A4B) grant, which is managed by the Welsh Assembly Government’s Department for Economy and Transport, and is financed by the Welsh Assembly Government and the European Union. 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary.......................................................................................................5 The following conclusions are drawn from this study......................................................5 The following recommendations are made in this study ................................................6 Preface ..............................................................................................................................8 Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part 1: Background and Context: The Infrastructure of the WelshLanguage Popular Music Industry from 1965–c.2000......................................................... 12 1.1 Overview...................................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Record companies and sales .............................................................................................. 13 1.3 TV, radio and Welshlanguage music journalism .................................................... -

Stereophonics Uk Arena Tour

PRODUCTION PROFILE: Stereophonics PRODUCTION PROFILE: Stereophonics Opposite: The tour enjoyed a Capital Sound audio rig which included Martin Audio’s MLA system and Avid consoles and outboard gear included a Roland SPX990 for vocal effects. Below: Toby Donovan, Dave Roden and Harm Schopman, the audio crew; Frontman Kelly Jones with his Shure Beta 58 microphone; For the monitor mix Jones used a combination of Ultimate Ears IEMs and Martin Audio Martin LE700 wedges, which he particularly likes due to the tone and smoothness; The lighitng rig from Neg Eath featured JTE and Martin Professional fixtures. prefer to lay the song out, verse chorus type of Jim Mills, Richard Armstrong, Damo Coad and The video content, a mixture of abstract deal, and this gives me tons of flexibility. I love the rigger was Andi Flack. Clark is keen to stress colour design then water footage, was mainly running the show, with cue stacks I would just his admiration for Neg Earth. “I have been using used for the stage gauze cloth screens. Six Barco get bored.” them since 2001. Their service is always top HD20 projectors were used, two positioned at Neg Earth supplied all the lighting; with crew notch. Julian Lavender has always been there for FOH, with the other four used for side screen chief Steve Kellaway working with Ian Lomas, me. I can’t say enough.” rear projection onto screens mainly used for STEREOPHONICS UK ARENA TOUR WITH A HIGHLY SUCCESSFUL EIGHTH STUDIO ALBUM, GRAFFITI ON THE TRAIN RELEASED ON THE BAND’S OWN RECORD LABEL, STYLUS RECORDS, WELSH SONGSMITHS STEREOPHONICS EMBARKED ON A UK ARENA. -

Karaoke Songs We Can Use As at 22 April 2013

Uploaded 3rd May 2013 Before selecting your song - please ensure you have the latest SongBook from the Maori Television Website. TKS No. SONG TITLE IN THE STYLE OF 21273 Don't Tread On Me 311 25202 First Straw 311 15937 Hey You 311 1325 Where My Girls At? 702 25858 Til The Casket Drops 16523 Bye Bye Baby Bay City Rollers 10657 Amish Paradise "Weird" Al Yankovic 10188 Eat It "Weird" Al Yankovic 10196 Like A Surgeon "Weird" Al Yankovic 18539 Donna 10 C C 1841 Dreadlock Holiday 10 C C 16611 I'm Not In Love 10 C C 17997 Rubber Bullets 10 C C 18536 The Things We Do For Love 10 C C 1811 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 24657 Hot And Wet 112/ Ludacris 21399 We Are One 12 Stones 19015 Simon Says 1910 Fruitgum Company 26221 Countdown 2 Chainz/ Chris Brown 15755 You Know Me 2 Pistols & R Jay 25644 She Got It 2 Pistols/ T Pain/ Tay Dizm 15462 Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down 23044 Everytime You Go 3 Doors Down 24923 Here By Me 3 Doors Down 24796 Here Without You 3 Doors Down 15921 It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down 15820 Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down 25232 Let Me Go 3 Doors Down 22933 When You're Young 3 Doors Down 15455 Don't Trust Me 3 Oh!3 21497 Double Vision 3 Oh!3 15940 StarStrukk 3 Oh!3 21392 My First Kiss 3 Oh!3 / Ke$ha 23265 Follow Me Down 3 Oh!3/ Neon Hitch 20734 Starstrukk 3 Oh3!/ Katy Perry 10816 If I'd Been The One 38 Special 10112 What's Up 4 Non Blondes 9628 Sukiyaki 4.pm 15061 Amusement Park 50 Cent 24699 Candy Shop 50 Cent 12623 Candy Shop 50 Cent 1 Uploaded 3rd May 2013 Before selecting your song - please ensure you have the latest SongBook from the Maori Television Website. -

10,000 Maniacs Beth Orton Cowboy Junkies Dar Williams Indigo Girls

Madness +he (,ecials +he (katalites Desmond Dekker 5B?0 +oots and Bob Marley 2+he Maytals (haggy Inner Circle Jimmy Cli// Beenie Man #eter +osh Bob Marley Die 6antastischen BuBu Banton 8nthony B+he Wailers Clueso #eter 6oA (ean #aul *ier 6ettes Brot Culcha Candela MaA %omeo Jan Delay (eeed Deichkind 'ek181Mouse #atrice Ciggy Marley entleman Ca,leton Barrington !e)y Burning (,ear Dennis Brown Black 5huru regory Isaacs (i""la Dane Cook Damian Marley 4orace 8ndy +he 5,setters Israel *ibration Culture (teel #ulse 8dam (andler !ee =(cratch= #erry +he 83uabats 8ugustus #ablo Monty #ython %ichard Cheese 8l,ha Blondy +rans,lants 4ot Water 0ing +ubby Music Big D and the+he Mighty (outh #ark Mighty Bosstones O,eration I)y %eel Big Mad Caddies 0ids +able6ish (lint Catch .. =Weird Al= mewithout-ou +he *andals %ed (,arowes +he (uicide +he Blood !ess +han Machines Brothers Jake +he Bouncing od Is +he ood -anko)icDescendents (ouls ')ery +ime !i/e #ro,agandhi < and #elican JGdayso/static $ot 5 Isis Comeback 0id Me 6irst and the ood %iddance (il)ersun #icku,s %ancid imme immes Blindside Oceansi"ean Astronaut Meshuggah Con)erge I Die 8 (il)er 6ear Be/ore the March dredg !ow $eurosis +he Bled Mt& Cion 8t the #sa,, o/ 6lames John Barry Between the Buried $O6H $orma Jean +he 4orrors and Me 8nti16lag (trike 8nywhere +he (ea Broadcast ods,eed -ou9 (,arta old/inger +he 6all Mono Black 'm,eror and Cake +unng &&&And -ou Will 0now Us +he Dillinger o/ +roy Bernard 4errmann 'sca,e #lan !agwagon -ou (ay #arty9 We (tereolab Drive-In Bi//y Clyro Jonny reenwood (ay Die9 -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People..