Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

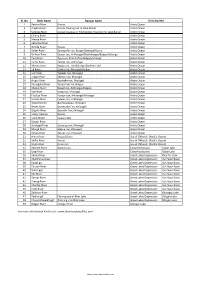

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Final Report on the Study of Value Chains for Live Animals/Meat and Hides/Skins in Mongolia

Final report on the study of value chains for live animals/meat and hides/skins in Mongolia Final Report as at 31 July 2015 A d d r e s s GFA Consulting Group GmbH Eulenkrugstraße 82 22359 Hamburg Germany Telefon +49 (40) 6 03 06 – 166 Fax +49 (40) 6 03 06 – 169 E-Mail [email protected] Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................................. 1 LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES ...................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 4 ONE. RESEARCH PROGRAM OF THE VALUE CHAIN STUDY ............................................................. 5 1.1. Objective of the study .......................................................................................................... 5 1.2. Methods of the study ........................................................................................................... 6 1.3. Study objects of the supply study ........................................................................................ 6 1.4. Study objects of the demand study ..................................................................................... 7 TWO. STUDY ON THE VALUE CHAIN OF LIVE ANIMALS AND MEAT ................................................ 8 2.1. Executive summary ............................................................................................................. -

Journal Biology 2004 3

Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences 2004 Vol. 2(1): 39-42 Hydrochemical Characteristics of Selenge River and its Tributaries on the Territory of Mongolia Bazarova J.G. 1, Dorzhieva S.G.1, Bazarov B.G. 1, Barkhutova D.D.2, Dagurova O.P.2, Namsaraev B.B. 2 and Zhargalova S.O.2 1Baikal Institute of Nature Management of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, 2Institute of General and Experimental Biology of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Hydrochemical research of the Selenge and its main tributary the Orkhon river on the territory of Mongolia has been conducted. Concentrations of the main water ions were measured. Distribution of - + heavy metals was determined. Dynamics of biogenic elements (NO3 , NH4 , phosphates) and degree of phenol pollution was determined. Key words: Baikal, biogenic, heavy metals, ions, phenol, Selenge River Introduction river is polluted along its entire length. To assess the current ecological condition in the Mongolian During the last 30-40 years Lake Baikal has part of the Selenge river basin, it is necessary to been influenced by various anthropogenic factors. implement hydrobiological and hydrochemical Industrial and household waste water have changed monitoring. It requires information not only of the chemical composition of Baikal with a chemical composition, but of biogenic components deterioration in water quality in the basin territory. in the processes of accumulation and According to sustainable development policy, transformation in water, bottom sediments and river protection of Baikal region is considered -

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora Beyond Tibet

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora beyond Tibet Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2019. “Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Dias- pora beyond Tibet.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 7–32. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/uranchimeg. Abstract This article discusses a Khalkha reincarnate ruler, the First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar, who is commonly believed to be a Géluk protagonist whose alliance with the Dalai and Panchen Lamas was crucial to the dissemination of Buddhism in Khalkha Mongolia. Za- nabazar’s Géluk affiliation, however, is a later Qing-Géluk construct to divert the initial Khalkha vision of him as a reincarnation of the Jonang historian Tāranātha (1575–1634). Whereas several scholars have discussed the political significance of Zanabazar’s rein- carnation based only on textual sources, this article takes an interdisciplinary approach to discuss, in addition to textual sources, visual records that include Zanabazar’s por- traits and current findings from an ongoing excavation of Zanabazar’s Saridag Monas- tery. Clay sculptures and Zanabazar’s own writings, heretofore little studied, suggest that Zanabazar’s open approach to sectarian affiliations and his vision, akin to Tsongkhapa’s, were inclusive of several traditions rather than being limited to a single one. Keywords: Zanabazar, Géluk school, Fifth Dalai Lama, Jebtsundampa, Khalkha, Mongo- lia, Dzungar Galdan Boshogtu, Saridag Monastery, archeology, excavation The First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar (1635–1723) was the most important protagonist in the later dissemination of Buddhism in Mongolia. Unlike the Mongol imperial period, when the sectarian alliance with the Sakya (Tib. -

Two Generations of Muslim Women in France: Creative Parenting, Identity and Recognition

delcroix:print 24/7/09 16:00 Page 87 TWO GENERATIONS OF MUSLIM WOMEN IN FRANCE: CREATIVE PARENTING, IDENTITY AND RECOGNITION by Catherine Delcroix In bringing up and educating their children, Muslim immigrant parents (coming ABSTRACT from North Africa and living in France) are very aware of the difficulty of the Key words: task. Their children face a double bind: on the one hand, French society asks creativity; them to ‘integrate’, that is to enter into labour markets and melt into French parenting; ways of life. On the other hand teachers, employers, the police and media Muslim; keep considering them as ‘the other’. Immigrant parents show tremendous France creativity in trying to help their children, boys and girls differently, to cope with this double bind. In France today there are approximately one educate their children to face the difficulties million families who come from North Africa. linked to economic instability: unemployment, Many of these are large families. Their children chronic shortage of money, and discrimination.2 are born in France and they are French citizens. For studying the educational strategies of Their language is French, and they are raised in these families, I have used a methodological French schools. They feel French. But given the approach based on the reconstruction of family colonial past of France, the metropolitan histories, drawn from life story interviews with French continue to consider them somehow as several members of each family: parents, chil- ‘the other’. This post-colonial attitude has very dren and so on. I have repeated these case damaging consequences, encouraging discrim- studies in many different regions and cities of ination by some teachers, by employers, by France. -

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River Valley Results of the 2005 Joint American-Mongolian Expedition to Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, Ogii nuur, Arkhangai aimag, Mongolia David E. Purcell and Kimberly C. Spurr Flagstaff, Arizona (USA) During the summer of 2005 an archaeological investigations, and What is known points to this area archaeological expedition jointly their results, are the focus of this as one of the most important mounted by the Silkroad Foun- article, which is a preliminary and cultural regions in the world, a fact dation of Saratoga, California, incomplete record of the project recently recognized by the U.S.A. and the Mongolian National findings. Not all of the project data UNESCO through designation of University, Ulaanbataar, investi- — including osteological analysis of the Orkhon Valley as a World gated two sites near the the burials, descriptions or maps Heritage Site in 2004 (UNESCO confluence of the Tamir River with of the graves, or analyses of the 2006). Archaeological remains the Orkhon River in the Arkhangai artifacts — is available as of this indicate the region has been aimag of central Mongolia (Fig. 1). writing. Consequently, the greater occupied since the Paleolithic (circa The expedition was permitted emphasis falls on one of the two 750,000 years before present), (Registration Number 8, issued sites. It is hoped that through the with Neolithic sites found in great June 23, 2005) by the Ministry of Silkroad Foundation, the many numbers. As early as the Neolithic Education, Culture and Science of different collections from this period a pattern developed in Mongolia. The project had multiple project can be reunited in a which groups moved southward goals: archaeological investiga- scholarly publication. -

Spring 2010 Far Horizons Newsletter

NEWSLETTER FAR HORIZONS ARCHAEOLOGICAL & CULTURAL TRIPS Volume 15, Number 1 • Spring 2010 Published Erratically by Far Horizons • P.O. Box 2546 • San Anselmo, CA 94979 USA (800) 552-4575 • (415) 482-8400 • fax (415) 482-8495 • www.farhorizons.com • email: [email protected] Dear Travelers, I am delighted to dedicate this newsletter to those participants who travel with Far Horizons repeatedly – thank you! In fact, we have included articles from some of our frequent travelers in which they eloquently describe their experiences exploring remarkable destinations with our fabulous study leaders. Don’t miss these evocative accounts of their adventures. There are only a very few spaces remaining on the September trip led by Professor Jonathan Phillips of History Channel fame. I am so pleased that people are excited about our Crusades trip! By the way, look for Professor Jonathan Phillips’ new book, Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades. We plan to design more itineraries relating to the medieval era, so keep watching our webpage. Are you a Bob Brier enthusiast (do you know anyone who isn’t!)? There are still a few spaces left on Bob’s Egypt in Rome May 10-20, 2010, and Oases of Egypt Oct 29 - Nov 15, 2010. Plus Bob Brier heads to Sudan in March of 2011. Be sure and read what former travelers have to say about Bob’s trips and register soon! With this newsletter we begin a new series written by Heather Stoeckley and Sara Barbieri, two members of the Far Horizons team who travel several times each year with our groups as tour manager. -

Sundowners Overland - Gobi Desert Explorer Page 1 of 6 Itinerary

Journey Itinerary Gobi Desert Explorer Days Westbound, Eastbound Countries Distance Activity level 16 Ulaanbaatar to Ulaanbaatar Mongolia 1,750 km Discover the very best of Mongolia, from the bustling capital Ulaanbaatar we journey across the steppe to Kharkhorin. We will encounter ancient Buddhist monasteries and the remarkable diversity of the Gobi Desert; sacred mountains, dinosaur ‘cemeteries’, flaming cliffs, singing sand dunes and spectacular canyons. Sundowners Overland - Gobi Desert Explorer Page 1 of 6 Itinerary Day 1: Ulaanbaatar Mongolia is the world’s most sparsely populated country with just 3 million people inhabiting the 1.5 million square kilometres of pristine desert, steppe and mountain. Almost half the population lives in its frenetic capital Ulaanbaatar where we will start our journey. Join your Tour Leader and fellow travellers on Day 1 at 5:00pm for your Welcome Meeting as detailed on your joining instructions. Meals - Day 1 – Dinner Day 2: To Bayangobi via Khustai National Park Beyond the city one million Mongolian’s still live a traditional nomadic or semi nomadic life and the horse is central to their existence. We visit the Gandan Monastery, with its huge gold Buddha, the spiritual home of the Mongolian people, before traveling to the Khustai National Park where wild horses, known as Tahki or Przewalski horses are bred and reintroduced to the wild. Once close to extinction, Takhi are the world’s only true wild horse. Mongolia is a country with such diverse landscapes and today we continue our way across the steppe to experience the uniqueness of the Bayangobi. Here we have the opportunity to hike in the stunning sand dunes that stretch over a distance of 80kms. -

Mongolia: Land of the Blue Sky June 3- 14, 2019

MONGOLIA: LAND OF THE BLUE SKY JUNE 3- 14, 2019 One of the most sparsely populated countries in the world, Mongolia still retains its natural beauty of diverse landscapes and habitats relatively intact along with its well-preserved unique nomadic culture. The open countryside of Mongolia is awe-inspiring, and all sense of urgency seems to dissipate into the famous Mongolian blue sky. Featuring one of Mongolia’s magnificent natural wonders, the Gobi Desert, and the historical highlight Kharakhorum, this trip offers a special opportunity to travel back in time to the untouched land of Genghis Khan and hospitable nomads. Discover the incredible scenery, diverse wildlife, ancient history, and traditional culture of Mongolia on this adventure-packed journey. GROUP SIZE: Up to 15 guests PRICING: $7,995 per person double occupancy / $9,550 single occupancy STUDY LEADERS: Andrew Berry, Lecturer on Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. Born in London, Andrew Berry has a degree in zoology from Oxford University and a PhD in evolutionary genetics from Princeton University. Combining the techniques of field biology with those of molecular biology, Berry’s work has been a search for evidence at the DNA level of Darwinian natural selection. He has published on topics as diverse as giant rats in New Guinea, mice on Atlantic islands, aphids from the Far East, and the humble fruit fly. At Harvard, he currently co-teaches courses on evolutionary biology, on the development of evolutionary thinking, and on the physical basis of biological systems. & Naomi Pierce, Hessel Professor of Biology and Curator of Lepidoptera in the Museum of Comparative Zoology. -

Zanabazar (1635-1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia

Zanabazar (1635-1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia Uranchimeg Tsultem ___________________________________________________________________________________ This is the author’s manuscript of the article published in the final edited form as: Tsultem, U. (2015). Zanabazar (1635–1723): Vajrayāna Art and the State in Medieval Mongolia. In Buddhism in Mongolian History, Culture, and Society (pp. 116–136). Introduction The First Jebtsundamba Khutukhtu (T. rJe btsun dam pa sprul sku) Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar is the most celebrated person in the history of Mongolian Buddhism, whose activities marked the important moments in the Mongolian politics, history, and cultural life, as they heralded the new era for the Mongols. His masterpieces of Buddhist sculptures exhibit a sophisticated accomplishment of the Buddhist iconometrical canon, a craftsmanship of the highest quality, and a refined, yet unfettered virtuosity. Zanabazar is believed to have single-handedly brought the tradition of Vajrayāna Buddhism to the late medieval Mongolia. Buddhist rituals, texts, temple construction, Buddhist art, and even designs for Mongolian monastic robes are all attributed to his genius. He also introduced to Mongolia the artistic forms of Buddhist deities, such as the Five Tath›gatas, Maitreya, Twenty-One T›r›s, Vajradhara, Vajrasattva, and others. They constitute a salient hallmark of his careful selection of the deities, their forms, and their representation. These deities and their forms of representation were unique to Zanabazar. Zanabazar is also accredited with building his main Buddhist settlement Urga (Örgöö), a mobile camp that was to reach out the nomadic communities in various areas of Mongolia and spread Buddhism among them. In the course of time, Urga was strategically developed into the main Khalkha monastery, Ikh Khüree, while maintaining its mobility until 1855. -

Ìîíãîë Íóòàã Äàõü Ò¯¯Õ, Ñî¨Ëûí ¯Ë Õªäëªõ Äóðñãàë

ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÀÉÌÃÈÉÍ ÍÓÒÀà ÄÀÕÜ Ò¯¯Õ, ÑΨËÛÍ ¯Ë ÕªÄËªÕ ÄÓÐÑÃÀË ISBN 978-99962-67-33-8 ÑΨËÛÍ ªÂÈÉÍ ÒªÂ ÌÎÍÃÎË ÍÓÒÀà ÄÀÕÜ Ò¯¯Õ, ÑΨËÛÍ ¯Ë ÕªÄËªÕ ÄÓÐÑÃÀË HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL IMMOVABLE MONUMENTS IN MONGOLIA X ÄÝÂÒÝÐ ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÀÉÌÀà 1 ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÀÉÌÃÈÉÍ ÍÓÒÀà ÄÀÕÜ Ò¯¯Õ, ÑΨËÛÍ ¯Ë ÕªÄËªÕ ÄÓÐÑÃÀË ÌÎíãÎë íóòàã äàõü ò¯¯õ, ñΨëûí ¯ë õªäëªõ äóðñãàë X äýâòýð ÀðõÀíãÀé ÀéìÀã 1 DDC 900 Ý-66 Зохиогч: Г.Энхбат Г.аНХСАНАА б.ДаваацЭрЭн Гэрэл зургийг: б.ДаваацЭрЭн П.Чинбат Гар зургийг: а.мӨнГӨНЦООЖ т.эРДЭнЭцОГт Г.аНХСАНАА Дизайнер: б.аЛТАНСҮх Орчуулагч: ц.цОЛмОн Жолооч: б.ЭрДЭнЭЧИМЭГ Зохиогчийн эрх хамгаалагдсан. © 2013, Copyrigth © 2013 by the Center of Cultural Соёлын өвийн төв, Улаанбаатар, монгол улс Heritage, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia Энэхүү цомгийг Соёлын өвийн төвийн зөвшөөрөлгүйгээр бүтнээр нь буюу хэсэгчлэн хувилан олшруулахыг хориглоно. монгол улс Улаанбаатар хот - 211238 Сүхбаатар дүүрэг Сүхбаатарын талбай 3 Соёлын төв өргөө б хэсэг Соёлын өвийн төв Шуудангийн хайрцаг 223 веб сайт: www.monheritage.mn и-мэйл: [email protected] Утас: 976-70110877 ISBN 978-99962-67-33-8 Соёл, Спорт, аялал Соёлын өвийн төв архангай аймгийн жуулчлалын яам музей 2 ÃÀÐ×Èà Өмнөх үг 4 Удиртгал 5 архангай аймгийн нутаг дахь түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалын тухай 18 архангай аймгийн нутаг дахь түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалын байршил 36 батцэнгэл сум 37 булган сум 46 Жаргалант 50 их тамир сум 55 Өгийнуур сум 61 Өлзийт сум 64 Өндөр-Улаан сум 68 тариат сум 73 төвширүүлэх сум 76 хангай сум 78 хайрхан сум 81 хашаат сум 85 хотонт сум 88 цахир сум 91 цэнхэр сум 94 цэцэрлэг сум 97 Чулуут 100 Эрдэнэмандал 103 Эрдэнэбулган 111 архангай аймгийн нутаг дахь түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалын жагсаалт 114 товчилсон үгийн тайлал 116 ашигласан ном бүтээлийн жагсаалт 117 ªÌÍªÕ ¯Ã СаЖЯ-ны харьяа Соёлын өвийн төв монгол нутагт оршин буй түүх, соёлын үл хөдлөх дурсгалыг анхан Сшатны байдлаар бүртгэн баримтжуулах, тоолох, хадгалалт хамгаалалт, ашиглалтын байдалд судалгаа хийх ажлыг 2008-2015 онд гүйцэтгэхээр төлөвлөн хэрэгжүүлж эхлээд байгаа билээ. -

Mongolia Exotic Tour

Mongolia Exotic Tour Key Information: Trip Length: 9 days/8 nights. Trip Type: Easy to Moderate. Tour Code: SMT-ORKHON-9D Specialty Categories: Adventure Expedition, Cultural Journey, Camel riding, Driving tour, Eco-Travel, Hiking, Hot spa, Local Culture, Nature & Wildlife. Meeting/Departure Points: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (excluding flights). Small Groups: 2-16 travelers-guaranteed! Best Season: Daily, June-September. Total Distance: about 2000kms/1243miles. Airfare or Train Included: No. Tour Customizable: Yes Tour Highlights: Upon your arrival in Ulaanbaatar, meet Samar Magic Tours team. Mongolia Exotic Tour takes you to the Natural Wonders of Central Mongolia. This journey designed especially for small groups, families, private, and funny travel. Exploration to Karakorum-the Genghis (Chinggis) Khan's 13th century capital, Orkhon Waterfall (also called Ulaan Tsutgalan)-this is perfect for swimming, fishing, short trekking and walks around the surrounding area, stop at VIII century Turkish monuments in the Orkhon Valley, Tsenkher Hot Spa and many more. Karakorum was the capital of the Mongol Empire in the 13th century and of the Northern Yuan in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in the north-western corner of the Ovorkhangai Province of Mongolia, near today's town of Kharkhorin, and adjacent to the Erdene Zuu monastery. They are part of the upper part of the World Heritage Site Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape. Ride horses on the steppes, meeting nomadic people, staying in a traditional tent, seeing grasslands and beautiful vistas. You will need to bring your Binoculars, telescopes and tripod. We would be pleased to have you join us! The Best Time to Travel to Mongolia: Begins in June.