CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE COMMUNITY SERVICES DEVELOPMENT at COLLEGE of the CANYONS a Thesis Submitted in Partial S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission WASHINGTON, DC 20554

BEFORE THE Federal Communications Commission WASHINGTON, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) All-Digital AM Broadcasting ) MB Docket No. 19-311 ) ) Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) MB Docket No. 13-249 ) ) ) To: The Commission COMMENTS OF THE CRAWFORD BROADCASTING COMPANY Crawford Broadcasting Company (“Crawford”) and its affiliates are licensees of 15 AM commercial broadcast stations1, all but two of which currently operate in the hybrid analog/digital mode. As such, we have great interest in the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to permit all AM stations to broadcast an all-digital signal using the HD Radio in-band on-channel (IBOC) mode known as MA3 on a voluntary basis (“Notice”), and we offer the following comments in support of this petition. I. Benefits of All-Digital AM Transmissions It has been well established for more than a decade of operation by many of our stations in the MA1 hybrid digital mode that AM stations stand to gain a great deal from digital operation. Greatly improved audio quality is at the forefront, with audio bandwidth comparable to FM broadcasts, stereo audio and receiver display of title/artist or program title information. When a receiver locks in the digital mode to one of our stations, particularly one playing music, as the receiver blends from analog to digital, the contrast is dramatic. The highs and lows of the audio open up, the stereo image widens out, and the noise that seems to be ever present on almost any AM frequency disappears. Listeners experiencing this effect for the first time are quite often amazed at how good an AM broadcast can sound in this mode. -

Attachment A

Attachment A _ -_ --_-- _4_.__ Figure 1 "'~ KfPH(TVl, ( GradeA _ ....... - . .. _- Flu ... ~KH.OT.FM.. IS: ~ ~ lmVIm ,// Sbow~ ,~cn / "~KMRR(FM) H i 1 mVIm KOMR(FML '.... 1 ",Vim o..oII~':"1\ - ~~:'i T."""1\.--~ .GIIf" Son en. $_ 1+1 Illy C. "V 1f4IiI " --.- K1VVV(TV) KolInIy Gi"adeA -. ,-"""""" uma TUrbyFill KKMR(FM) APP lmVim Veil SQn .- EJl<dt : Al1Alca CIlnlttl Si."" VlI1lI """... Sulbe Rl.iby RaPlro E-atl Un"""" $1_ . BlaCk COnIou... HBC S1allons • Red Contours NoglIios ~. -- D_ 50 0 100 150 200 JOG ~ , ",,",~_~,3 RADIO/TV CROSS OWNERSHIP STUDY PHOENIX. ARIZONA {hI 1'11:11. I,1IIHhIJ &. Rm:i..k·~, Inc Saras~Jla. f:IHnd;1 VOICE STUDY - PHOENIX, AZ RADIO METRO Independent TV Daily and Radio Newspapers Cable Owners 29 1 Detailed View (after proposed transaction) I. Univision Communications Inc. KTVW-TV Phoenix, AZ KFPH(TV) Flagstaff, AZ KHOT-FM Paradise Valley, AZ KHOV-FM Wickenburg, AZ KOMR-FM Sun City, AZ KMRR-FM Globe,AZ KKMR-FM Arizona Ci ,AZ 2. Gannett Co., Inc. KPNX(TV) Mesa,AZ KNAZ-TV Flagstaff, AZ KMOH-TV Kingman, AZ A.H. Belo Corp. KTVK(TV) Phoenix, AZ ~ KASWTV Phoenix, AZ I 4. I Meredith Corporation KPHO-TV Phoenix, AZ ~-- - I 5. KUSK, Inc. KUSK(TV) Prescott, AZ 6. Arizona State Board ofRegents For Arizona KAET(TV)* Phoenix, AZ State University KSAZ-TV Phoenix, AZ 7 Fox Television Stations, Inc. 1L. __ KUTP TV Phoenix, AZ ~I Scripps Howard Broadcasting Company KNXV-TV Phoenix, AZ ! 9. I Trinity Broadcasting ofArizona, Inc. KPAZ-TV Phoenix, AZ ! !e---- I 10. -

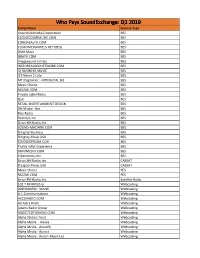

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

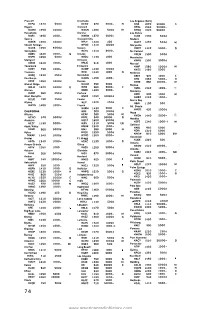

Jones-Log-12-OCR-Page-0075.Pdf

Prescott Coachella Los Angeles (Cont) KTPA 1370 500d KCHV 970 5000- N KNX 1070 50000 c Rogers Concord KPOL 1540 50000- KAMO 1390 lOOOd KWUN 1480 500d M KTNQ 1020 50000 Russellville Corona Los Banos KARY 1490 1000- KWRM 1370 5000- KLBS 1330 500d Searcy Crescent City Madera KWCK 1300 lOOOd KPLY 1240 250 KHOT 1250 500d M Siloam Springs KPOD 1310 lOOOd Marysville KUOA 1290 5000d Delano KMYC 1410 5000- D Springdale KCHJ 1010 5000- Mc Farland KBRS 1340 1000- G Dinuba KXEM 1590 500d KSPR 1590 500d KRDU 1130 1000 Mendocino Stuttgart El Cajon KMFB 1300 5000 d KWAK 1240 1000- KMJC 910 1000 Merced Texarkana El Centro KWIP 15BO lOOOd M KOSY 790 1000- KAMP 1430 lOOOd KYOS 1480 5000 Trumann KXO 1230 1000 N Modesto KXRQ 1530 250 d Escondido KBEE 970 1000 c Van Buren KOWN 1450 1000- KFIV 1360 5000- D KFDF 15BO lOOOd Eureka KTRB B60 10000- M Walnut Ridge KHUM 790 5000 Mojave KINS KRLW 1320 lOOOd G 980 5000- c KOOL 1340 1000- Warren KRED 1480 5000- Monterey KWRF 860 250 d Fortuna KIDD 630 1000 M West Memphis KNCR 1090 lOOOO d KMBY 1240 1000- 730 250d Fawler KSUD Morro Bay Wynne 1220 250d KLIP KBAI 1150 500 KWYN 1400 1000- Fresno Mt. Shasta KARM 1430 5000 c KWSD 620 lODOd CALIFORNIA KBIF 900 lOOOd Napa Alturas KEAP 980 500d M KVON 1440 5000- KCNO 570 5000d KFRE 940 50000 G Needles Anaheim KGST 1600 5000d KSFE 1340 1000-f M KEZY 1190 5000- KIRV 1510 500d EG Oakland Apple Valley KMAK 1340 1000- KABL 960 5000 KAVR 960 5000d KMJ 5BO 5000 N KDIA 1310 5000 Aptos KXEX 1550 500d KNEW 910 5000 EM tKKAP 1540 lOOOd KYNO 1300 5000- Oceanside Arcata Ft. -

The Newsletter of Crawford Broadcasting Company Corporate Engineering

The Newsletter of Crawford Broadcasting Company Corporate Engineering DECEMBER 2014 • VOLUME 24 • ISSUE 12 • W.C. ALEXANDER, CPBE, AMD, DRB EDITOR Winding Down and Looking Ahead engineering personnel complement. Last spring, we It’s always a bit of a relief when we get into made some radical changes in Chicago, bringing December of each year, that is if we have gotten all Rick Sewell back to Crawford Broadcasting of our projects done for the year. Thankfully that is Company as Engineering Manager of that incredibly the case this year. There are no eleventh-hour busy market. Mack Friday, the longtime Senior projects to wrap up. Everything is done and we can Engineer in that operation, retired at the end of begin thinking about the coming year and its projects September, and Art Reis departed to pursue his and demands. contract engineering business. In Detroit, another The budget is finished and finalized for busy and important CBC market, Brian Kerkan came 2015. We pared it down quite a bit from the original aboard as Chief Engineer. What a difference that has draft but kept the essence in place. The big project for made in the technical excellence of that operation! 2015 is the transition to Wheatstone AOIP Last month, Bill Agresta left KBRT to infrastructure in several key markets, specifically pursue other interests. We wish Bill all the best and KBRT (Southern California), Chicago, Detroit and look forward to a continued good relationship with Birmingham. We will also complete the transition to him. We have gone to a contract engineering model AOIP in Denver where the on-air Nexgen in that market. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Morning Mania Contest, Clubs, Am Fm Programs Gorly's Cafe & Russian Brewery

Guide MORNING MANIA CONTEST, CLUBS, AM FM PROGRAMS GORLY'S CAFE & RUSSIAN BREWERY DOWNTOWN 536 EAST 8TH STREET [213] 627 -4060 HOLLYWOOD: 1716 NORTH CAHUENGA [213] 463 -4060 OPEN 24 HOURS - LIVE MUSIC CONTENTS RADIO GUIDE Published by Radio Waves Publications Vol.1 No. 10 April 21 -May 11 1989 Local Listings Features For April 21 -May 11 11 Mon -Fri. Daily Dependables 28 Weekend Dependables AO DEPARTMENTS LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 4 CLUB LIFE 4 L.A. RADIO AT A GLANCE 6 RADIO BUZZ 8 CROSS -A -IRON 14 MORNING MANIA BALLOT 15 WAR OF THE WAVES 26 SEXIEST VOICE WINNERS! 38 HOT AND FRESH TRACKS 48 FRAZE AT THE FLICKS 49 RADIO GUIDE Staff in repose: L -R LAST WORDS: TRAVELS WITH DAD 50 (from bottom) Tommi Lewis, Diane Moca, Phil Marino, Linda Valentine and Jodl Fuchs Cover: KQLZ'S (Michael) Scott Shannon by Mark Engbrecht Morning Mania Ballot -p. 15 And The Winners Are... -p.38 XTC Moves Up In Hot Tracks -p. 48 PUBLISHER ADVERTISING SALES Philip J. Marino Lourl Brogdon, Patricia Diggs EDITORIAL DIRECTOR CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Tommi Lewis Ruth Drizen, Tracey Goldberg, Bob King, Gary Moskowi z, Craig Rosen, Mark Rowland, Ilene Segalove, Jeff Silberman ART DIRECTOR Paul Bob CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Mark Engbrecht, ASSISTANT EDITOR Michael Quarterman, Diane Moca Rubble 'RF' Taylor EDITORIAL ASSISTANT BUSINESS MANAGER Jodi Fuchs Jeffrey Lewis; Anna Tenaglia, Assistant RADIO GUIDE Magazine Is published by RADIO WAVES PUBLICATIONS, Inc., 3307 -A Plco Blvd., Santa Monica, CA. 90405. (213) 828 -2268 FAX (213) 453 -0865 Subscription price; $16 for one year. For display advertising, call (213) 828 -2268 Submissions are welcomed. -

Inside This Issue

News Serving DX’ers since 1933 Volume 82, No. 2● October 20, 2014● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 2 … AM Switch 16 … International DX Digest 32 … Geo Indices/Space Wx 6 … QSL Revival Committee 24 … Oregon Cliff DXPedition 33 …. Confirmed DXer 7 … Domestic DX Digest East 29 … Membership Report 33 … Unreported Station List 12 … Domestic DX Digest West 30 … DX Toolbox 35 … Tower Site Calendar From the Publisher: Well, we were hoping shipping box and manual, but no speaker. that with a biweekly publishing schedule we Contact him at [email protected] or (402) could fill up each issue of DX News … and so far 330‐7758. $500, shipping included from 13312 it’s working, with a full 36‐pager this time. Westwood Lane, Omaha, NE 68144‐3543. We are always looking for DX‐related material Close‐Out on DXN Back Issues: Back issues for publication. Submit your DX reports to the of DX News from issue 55‐28 through 75‐26 are relevant column editor, and material that falls available from NRC HQ. You can request outside the regular columns to the publisher at individual issues to complete your collection or [email protected]. complete years. Contact Wayne Heinen at the The annual Tower Site Calendar, prepared addresses on the back page with requests. You’ll and sold by NRC member Scott Fybush, is now be notified of the cost of shipping and the issues available for 2015 … see page 35 for details. It’s will be packed and shipped when payment is worth noting that, while DX News doesn’t accept received. -

Services Who Have Paid 2016 Annual Minimum Fees Payments Received As of 07/31/2016

Services who have paid 2016 annual minimum fees payments received as of 07/31/2016 License Type Service Name Webcasting 181.FM Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Christian Music) Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Religious) Webcasting 70'S PRESERVATION SOCIETY Webcasting 8TRACKS.COM Webcasting A-1 COMMUNICATIONS Webcasting ABERCROMBIE.COM Webcasting ACAVILLE.COM Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting AD ASTRA RADIO Webcasting AD VENTURE MARKETING DBA TOWN TALK RADIO Webcasting ADAMS RADIO GROUP Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting AGM BAKERSFIELD Webcasting AGM NEVADA, LLC Webcasting AGM SANTA MARIA, L.P. *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright Act, and it does not waive the rights of artists or copyright owners that receive such payments. Services who have paid 2016 annual minimum fees payments received as of 07/31/2016 Webcasting AIBONZ Webcasting AIR ALUMNI Webcasting AIR1.COM Webcasting AIR1.COM (CHRISTMAS) Webcasting AJG CORPORATION Webcasting ALL MY PRAISE Webcasting ALLWEBRADIO.COM Webcasting ALLWORSHIP.COM Webcasting ALLWORSHIP.COM (CONTEMPORARY) Webcasting ALLWORSHIP.COM (INSTRUMENTAL) Webcasting ALLWORSHIP.COM (SPANISH) Webcasting ALOHA STATION TRUST Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - ALASKA Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - AMARILLO Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - AURORA Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - AUSTIN-ALBERT LEA Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - BAKERSFIELD *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright -

For Public Inspection Comprehensive

REDACTED – FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION COMPREHENSIVE EXHIBIT I. Introduction and Summary .............................................................................................. 3 II. Description of the Transaction ......................................................................................... 4 III. Public Interest Benefits of the Transaction ..................................................................... 6 IV. Pending Applications and Cut-Off Rules ........................................................................ 9 V. Parties to the Application ................................................................................................ 11 A. ForgeLight ..................................................................................................................... 11 B. Searchlight .................................................................................................................... 14 C. Televisa .......................................................................................................................... 18 VI. Transaction Documents ................................................................................................... 26 VII. National Television Ownership Compliance ................................................................. 28 VIII. Local Television Ownership Compliance ...................................................................... 29 A. Rule Compliant Markets ............................................................................................ -

1. Outlet Name 2. Anchorage Daily News 3. KVOK-AM 4. KIAK-FM 5

1 1. Outlet Name 2. Anchorage Daily News 3. KVOK-AM 4. KIAK-FM 5. KKED-FM 6. KMBQ-FM 7. KMBQ-AM 8. KOTZ-AM 9. KOTZ-AM 10. KUHB-FM 11. KASH-FM 12. KFQD-AM 13. Dan Fagan Show - KFQD-AM, The 14. Anchorage Daily News 15. KBFX-FM 16. KIAK-FM 17. KKIS-FM 18. KOTZ-AM 19. KUDU-FM 20. KUDU-FM 21. KXLR-FM 22. 11 News at 6 PM - KTVA-TV 23. KTVA-TV 24. 2 News Morning Edition - KTUU-TV 25. 2 News Weekend Late Edition - KTUU-TV 26. 11 News at 6 PM - KTVA-TV 27. KTVA-TV 28. KTVA-TV 29. 11 News This Morning - KTVA-TV 30. 2 NewshoUr at 6 PM - KTUU-TV 31. 11 News at 6 PM - KTVA-TV 32. 11 News at 10 PM - KTVA-TV 33. 11 News at 10 PM - KTVA-TV 34. KTVA-TV 35. KTVA-TV 36. 11 News at 10 PM - KTVA-TV 37. 11 News at 5 PM - KTVA-TV 38. 11 News at 6 PM - KTVA-TV 39. 2 News Weekend Late Edition - KTUU-TV 40. 2 News Weekend 5 PM Edition - KTUU-TV 41. KTUU-TV 42. KUAC-FM 43. KTUU-TV 44. KTUU-TV 45. 2 NewshoUr at 6 PM - KTUU-TV 46. KTUU-TV 2 47. KTVA-TV 48. KTUU-TV 49. Alaska Public Radio Network 50. KICY-AM 51. KMXT-FM 52. KYUK-AM 53. KTUU-TV 54. KTUU-TV 55. KTVA-TV 56. Anchorage Daily News 57. Anchorage Daily News 58. Fairbanks Daily News-Miner 59. -

TV Channel 5-6 Radio Proposal

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Promoting Diversification of Ownership ) MB Docket No 07-294 in the Broadcasting Services ) ) 2006 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 06-121 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) 2002 Biennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 02-277 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) Cross-Ownership of Broadcast Stations and ) MM Docket No. 01-235 Newspapers ) ) Rules and Policies Concerning Multiple Ownership ) MM Docket No. 01-317 of Radio Broadcast Stations in Local Markets ) ) Definition of Radio Markets ) MM Docket No. 00-244 ) Ways to Further Section 257 Mandate and To Build ) MB Docket No. 04-228 on Earlier Studies ) To: Office of the Secretary Attention: The Commission BROADCAST MAXIMIZATION COMMITTEE John J. Mullaney Mark Lipp Paul H. Reynolds Bert Goldman Joseph Davis, P.E. Clarence Beverage Laura Mizrahi Lee Reynolds Alex Welsh SUMMARY The Broadcast Maximization Committee (“BMC”), composed of primarily of several consulting engineers and other representatives of the broadcast industry, offers a comprehensive proposal for the use of Channels 5 and 6 in response to the Commission’s solicitation of such plans. BMC proposes to (1) relocate the LPFM service to a portion of this spectrum space; (2) expand the NCE service into the adjacent portion of this band; and (3) provide for the conversion and migration of all AM stations into the remaining portion of the band over an extended period of time and with digital transmissions only.