PDF (Volume 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literary Studies

LITERARY 2020 STUDIES LITERARY STUDIES Contents Gothic 2 Periodical & Print Culture 39 Shakespeare & Renaissance 7 Theory 41 Eighteenth Century & Romanticism 13 Postcolonial 48 Victorian 17 American & Atlantic 49 Modernism 24 Scottish 57 Twentieth Century 33 Arabic 65 Poetry 36 How to Order 71 Music & Sound 37 Letter from the team We’re kicking 2020 off with the publication of a new textbook in American and Atlantic Literature, Transatlantic Rhetoric: Speeches from the American Revolution to the Suffragettes by Tom Wright (pg 52), which presents over 70 speeches from a range of activists, politicians, fugitive slaves and preachers. We’re thrilled to be expanding our Edinburgh Companions to Literature and the Humanities series with volumes in the fields of Gothic Studies (pg 4), Modernism (pg 25), Refugee Studies (pg 33) and Music & Sound (pg 38). Our Edinburgh Critical Studies in Victorian Culture series is bustling with 11 new volumes as well as 8 releasing in paperback (pg 20-23). Look out for The Edinburgh History of Reading publishing in April 2020 in 4 volumes: Early Readers, Modern Readers, Subversive Readers and Common Readers (pg 40). Providing a cultural history and political critique of Scottish Devolution, Scott Hames brings us the thought-provoking The Literary Politics of Scottish Devolution: Voice, Class, Nation (pg 58). PS. Check out the new volumes in the critical editions of Scottish writers John Galt, John Gibson Lockhart, James Boswell as well as Walter Scott’s Poetry (pg 60 onwards). Jackie Jones Michelle Houston Ersev Ersoy Carla Hepburn Kirsty Andrews Editorial Editorial Editorial Marketing Marketing James Dale Eliza Wright Rebecca Mackenzie Production Production Design Cover image: Reading on a Windy Day, Illustration by Bila in ‘Blanco y Negro’. -

The History of British Women's Writing, 1920–1945, Volume Eight

The History of British Women's Writing, 1920-1945 Volume Eight Maroula Joannou ISBN: 9781137292179 DOI: 10.1057/9781137292179 Palgrave Macmillan Please respect intellectual property rights This material is copyright and its use is restricted by our standard site license terms and conditions (see http://www.palgraveconnect.com/pc/connect/info/terms_conditions.html). If you plan to copy, distribute or share in any format including, for the avoidance of doubt, posting on websites, you need the express prior permission of Palgrave Macmillan. To request permission please contact [email protected]. The History of British Women’s Writing, 1920–1945 Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to University of Strathclyde - PalgraveConnect - 2015-02-12 - PalgraveConnect of Strathclyde - licensed to University www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137292179 - The History of British Women©s Writing, 1920-1945, Edited by Maroula Joannou The History of British Women’s Writing General Editors: Jennie Batchelor and Cora Kaplan Advisory Board: Isobel Armstrong, Rachel Bowlby, Carolyn Dinshaw, Margaret Ezell, Margaret Ferguson, Isobel Grundy, and Felicity Nussbaum The History of British Women’s Writing is an innovative and ambitious monograph series that seeks both to synthesize the work of several generations of feminist scholars, and to advance new directions for the study of women’s writing. Volume editors and contributors are leading scholars whose work collectively reflects the global excellence in this expanding -

Delmore Schwartz Papers, 1923-1966

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6g50078g No online items Finding Aid for the Delmore Schwartz papers, 1923-1966 Processed by Josh Fiala, March 2012; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Delmore Schwartz 1005 1 papers, 1923-1966 Descriptive Summary Title: Delmore Schwartz papers Date (inclusive): 1923-1966 Collection number: 1005 Creator: Schwartz, Delmore, 1913-1966 Extent: 70 boxes (35 linear ft.) Abstract: Delmore David Schwartz (1913-1966) was an English professor, editor (1943-47) and associate editor (1947-55) of the Partisan Review, and the poetry editor of the New republic (1955-57). He also wrote poetry, plays, essays, translations, and stories, including In dreams begin responsibilities (1938), The world is a wedding (1948), and Summer knowledge: new and selected poems, 1938-1958 (1959), which won the Bollingen Prize in poetry and the Shelley Memorial Award in 1960. The collection consists of books and journals from Schwartz's library, most of which are heavily-annotated with his notes, nine holographic notebooks, and correspondence. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. -

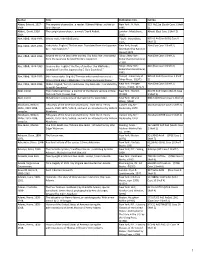

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

Lesbian Modernism I Hannah Roche

Day One | April 12th Panel 1a | Lesbian Modernism I Hannah Roche (University of York) Conceiving the Lesbian Hero: Radclyffe Hall, Adam’s Breed, and Modernism’s Queer Child. In 1927, just a year before the publication and trial for obscenity of The Well of Loneliness, Radclyffe Hall’s fourth novel achieved the unusual honour of winning both the Prix Femina Vie Heureuse and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. Adam’s Breed (1926), which probes the psyche of a spiritually starved Italian‐English waiter in Soho, raised Hall’s profile both as a writer and as a curiosity: public attention was drawn to the ‘distinctive figure in the literary world of London [who] is known everywhere for her Eton crop and her monocle’ (Daily News, 4th January 1928). Yet in spite of its considerable commercial success and remarkable critical acclaim, Adam’s Breed could not withstand the knock to Hall’s reputation dealt by the trial of The Well. Almost ninety years and a Virago Modern Classics edition (1985) later, Adam’s Breed has failed to secure a readership beyond the relatively small world of serious Hall criticism. This paper calls for the recognition of Adam’s Breed not only as a significant modern(ist) novel but also as an altogether necessary precursor to The Well. Expanding the category of ‘lesbian writing’, my paper raises important questions about how and why we might read lesbianism as the focus of an ostensibly ‘straight’ (and linear) novel. I explore the ways in which Hall’s preoccupation with breeds, not only as a keen dog‐fancier but more weightily as a proponent of homosexuality as a congenital condition, is played out in Adam’s Breed’s essentialist take on national ‘types’. -

Bibliography of Woolf Studies Published in 2003 (With Addenda for Previous Years). Updated and Corrected January 2004

Bibliography of Woolf Studies Published in 2003 (with addenda for previous years). Updated and corrected January 2004. Compiled by Mark Hussey Note: To save trees, I have listed only one article pertaining to The Hours. pre-2000 addenda Parker, R. “ Killing the Angel in the House: Creativity, Femininity and Aggression.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 79.4 (August 1998): 757-74. Schrecker, T. “Money Matters: A Reality Check with Help from Virginia Woolf.” Social Indicators Research 40.1/2 (1997): 99-123. 2000 Addenda Alexander, S. “Room of One’s Own” 1920s Feminist Utopias.” Women: A Cultural Review 11.3 (1 Oct. 2000): 273-88. Friedrichsen, A. “Magie der Vermahlung–Bermerken zu einer Asthetik der ‘Zwischensphare’ in Virginia Woolfs Lappin and Lapinova und Ilse Aichingers Engel der Nacht.” Orbis Litterarum 55.3 (June 2000): 211-34. Johnson, J. “Literary Geography: Joyce, Woolf and the City.” City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action 4.2 (1 July 2000): 199-214. Monte, S. “Ancients and Moderns in Mrs. Dalloway.” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly 61.4 (1 Dec. 2000): 587-616. Scheff, T. J. Multipersonal Dialogue in Consciousness: An Incident in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 7.6 (2000): 3-19. Usui, Masami. “Miyeko Kamiya’s Encounter with Virginia Woolf: A Japanese Woman Psychiatrist’s Waves of Her Own.” Doshisha Literature 43 (2000): 1-26. -----. “Woolf’s Search for Space in Between the Acts.” Doshisha Studies in English 72 (2000): 25-48. 2001 Addenda–Articles, Book Chapters, Books Aragon, Asuncion. “El genero y sus desfiladeros en el cine actual.” In Mercedes Bengoechea and Marisol Morales, eds. -

Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, and Their Victorian Masters

Ecumenical Craft: Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, and their Victorian Masters Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Holler, Seth C. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 00:46:36 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/323220 ECUMENICAL CRAFT: EVELYN WAUGH, GRAHAM GREENE, AND THEIR VICTORIAN MASTERS by Seth C. Holler __________________________ Copyright © Seth C. Holler 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Seth Holler, titled “Ecumenical Craft: Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, and their Victorian Masters” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________________________________________ Date: May 9, 2014 Gerald Monsman _____________________________________________________ Date: May 9, 2014 Suresh Raval _____________________________________________________ Date: May 9, 2014 Homer Pettey Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement.