This Is My Tattoo,” Intersections 11, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perception of Tattoos in Contemporary Japanese Society

LUND UNIVERSITY • CENTRE FOR EAST AND SOUTH-EAST ASIAN STUDIES Perception of Tattoos in Contemporary Japanese Society Author: Monika Rusiňáková Supervisor: Paul O’Shea Master’s Programme in Asian Studies Spring semester 2019 Abstract This thesis analyses five in-depth interviews on Japanese tattoo culture conducted by the author and ten short interviews with tattooed Japanese people published by Japanese online tattoo magazine. The study focuses on inclusion and exclusion of tattooed Japanese people in contemporary Japanese society, relying on labeling theory and collectivism. The findings suggest that significant tattoo stigmatization prevails in contemporary Japanese society. Tattoos are often percieved as a bad label that is required to be concealed with cloths or make-up. Nonetheless, the label was accepted by the majority of the interviewees who did not want to advocate for their rights of individualistic self-expression. Having said that, there were some participants who refused to submit to the society’s demand for good adjustment. I argue that the willingness to good adjustment is corelated with the values of collectivism. Keywords: Tattoos, Japanese society, Labelling theory, Collectivism 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Statement of Purpose and Research Question ............................................................................... 4 1.2 Research Value ............................................................................................................................. -

2017 Tattoo Hebrew

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 7 – Issue: 3 July - 2017 Tattoo Hebrew: An Analysis of Miami Ink’s Presentation of Jewish Tattoo Themes Joseph Robert Nicola, Century College, Minnesota, U.S.A Abstract Tattoos are growing in popularity among people of the Jewish faith. The following analysis examines the Jewish tattoo narrativespresented in the first American television program about tattooing, Miami Ink. Narrative Paradigm Theory is utilized to explore specific Jewish tattoo themes communicated. Keywords: Jewish, tattoo, television, stigma, narrative paradigm © Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies 146 Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 7 – Issue: 3 July - 2017 The TLC network reality series, Miami Ink, follows four tattoo artists and the clientele they tattoo in South Beach, Florida. Miami Ink is the first American reality television series about a tattoo parlor, and the first show completely devoted to tattoos (Hibberd, 2005; Oldenburg, 2005). Miami Inkoriginally ran from 2005 to 2008 (Saraiya, 2014). The show continues to air in syndication worldwide in over 160 countries (Tattoodo, 2015, 2014; Thobo-Carlsen & Chateaubriand, 2014). Relevance for Studying the Topic Research into the growing popularity of tattoos in America has attributed this rise of acceptance to open communication from the tattoo industry and positive media exposure of tattoos (DeMello, 2000; Wyatt, 2003; Yamada, 2009). With these media influences helping advance the popularity of tattoos, it is then relevant to look closely at the first television show dedicated specifically to tattooing. This analysis will examine the Jewish tattoo themes presented in the show and what they accomplish in terms of meaning. -

FIRA's Secret Sauce

Inside: Seacoast Holidays ALSO INSIDE: TV LIstINGS 40,000 COPIES Please Deliver Before FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 2006 Vol. 32 | No. 46 | 2 Sections |40 Pages FIRA’s Secret Sauce Non-profit association is pure protein for 30-plus local independent restaurants, providing value-laden consumer promotions while fortifying their purchasing power BY MICHAEL P. CONNELLY OWNER & PUBLISHER Cyan ATLANTIC NEWS t has become commonplace, chain Magenta restaurants are popping up instantly Iall around us. You probably didn’t notice this alarming trend as they navigate through the town Yellow zoning and planning process on the Sea- coast, but you can’t mistake their arrival during the construction phase as you travel Black the area. You see the balloons and the hoopla once they’ve opened. It’s at that moment in the blink of an eye when you see the competitive landscape change forever for the many longstanding locally owned restaurants. Today it’s a TGI Fridays, tomorrow a Chili’s, Applebee’s, or Pizzeria UNO. And it’s growing. Suddenly we’ve become “Californian- ized,” losing our New England flavor. FIRA Continued on 26A• The Perfect Gift! Voted World’s Best For Families 6 Years In A Row at The World Travel Awards One Gift Card Beaches is the ultimate family getaway that Welcomed at more than 30 includes non-stop fun with refined luxury. of the Area’s Favorite Restaurants All inclusive highlights: • Four family resorts located on SAVE 2 exotic islands. UP TO Give & Receive! • MULTI-CHOICE GOURMET DINING at up to 10 restaurants. % Limited Time Offer: Purchase a • Supervised KIDS KAMP. -

Tv Pg 5 12-11.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, December 11, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle FUN BY THE NUM B ERS will have you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, column and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESD A Y ’S TUESDAY EVENING DECEMBER 11, 2007 WEDNESDAY EVENING DECEMBER 12, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone CSI: Miami: Burned CSI: Miami: Kill Switch The Sopranos Mob boss deals with Paranormal CSI: Miami: Burned CSI: Miami: Bloodline CSI: Miami: Rush (TV14) CSI: Miami: Just Mur- Paranormal Paranormal CSI: Miami: Bloodline 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E (TV14) (HD) (HD) dered (TV14) (HD) (R) (HD) (R) (HD) (TV14) (HD) (TV14) (HD) (TV14) (HD) family issues. (TV14) (HD) (R) (HD) (TV14) (HD) Pushing Daisies: Private Practice (TV14) (:02) Dirty Sexy Money: Pilot KAKE News Nightline (N) (:01) Jimmy Kimmel Live Shrek Halls (:32) Pooh According Jim According Jim Boston Legal: No Brains Left KAKE News Nightline (N) (:01) Jimmy Kimmel Live 46 ABC 46 ABC (HD) (TVY) (R) (R) Behind (HD) at 10 (TV14) Corpsicle (N) (HD) (R) (HD) (TVPG) (R) (HD) at 10 (TV14) Anaconda Adventure Alligators American alli- Animal Precinct: Cases of Big Cat Diary: Battle for Anaconda Adventure Growing Up .. -

Ny Ink Season 4 Premiere

Ny ink season 4 premiere Season, Episodes, Season Premiere, Season Finale. 1, 8, June 2, (), July 21, (). 2, 10, December 29, No. of seasons: 3. Documentary · Ami James, a breakout from Miami Ink, will open a new shop, Wooster Street "The Walking Dead" Cast Tease Season 8 · IMDb on the Scene 10 August AM, | Variety - TV News · Cgm interviews Megan Missing: premiere. –AMERICA'S WORST TATTOOS & NY INK premiere Thursday, April 4 at 9 meet tattoo mistakes on Thursday, April 4 with the series premiere of TLC's AMERICA'S WORST TATTOOS and season three premiere of NY INK. NY Ink Official Site. Watch Full Episodes, Get Behind the Scenes, Meet the Cast, and much more. Stream NY Ink FREE with Your TV Subscription!Missing: premiere. Ink. M likes. Welcome to the Official Facebook page for TLC's NY Ink! Change of season is approaching -- maybe some new ink is in your future!? LA Ink. New Season of VH1's BLACK INK CREW to Premiere 8/24 engagement to Ceaser, but Ceaser struggles with the idea of leaving New York. OFFICIAL WEBSITE. Watch the full episode online. After leaving Black Ink closed for a month, Ceaser is back in Harlem. In North Carolina. Black Ink Crew | Official Season 4 Super Trailer | Premieres April 4th + a lot of surprises in store for us from. In the Season 4 premiere, Ceaser reopens Black Ink after it's been closed for a Dutchess spends her last days in New York City attempting to make amends. Our favorite crew of black New York tattoo artists have returned for a fourth In the Season 4 premiere. -

Kids Eat Free!!

VOLUME 45, NUMBER 13 WEEK OF APRIL 21 - 27, 2007 FREE Photo by B&0ARA STEVELMAN Samantha Stevelman, age 18 months, discovers her shadow on Rue Bayou while in the care of her brother JJ, 14. They are from South Salem, NY and visiting their grandparents on Sanibel. MONDAY NIGHT IS PRIME TIME!! Served with baked Idaho potato KIDS EAT FREE!! & corn on the cob Snow Crab Grouper EVERYDAY! Shrimp Open Mon - Sat @11 am Sunday 9:00am Served with !*rench Fries & corn on the cob 2330 Palm Ridge Rd. Sanibel Island With the Purchase of One $15" and up Adult Entree You Receive One Kids Meal for Children 10 & under 37 items on the "Consider the Kids" menu. Not good with any other promotion or discount. All specials subject to availability. This promotion good through May 7, 2006 and subject to change at any time. Sunday 9:00 -12:00 noon Master Card, \ >sa, Discover Credit Cards Accepted NoTtolidays, Must present ad. 2 • Week of April 21 -27,2006 ISLANDER Drastic price reductions offered on selected properties in our area! Condos, Lots, Homes • Inventory list availableprior to sale Call any ResortQuest Real Estate Saks office to receive a map and directions* MLS LOCATION ORIG. PRICE SALE PRICE COtMNTS 260058S 1457 Albatross fid $784t5W $772,000 Sanibd (3/2.5) Ground leveifiome w/ pool ypgrades, ultimate privacy, 2600391 923 Aftadena Or, $1,695,000 $1,405,(WO Ft. Mytts, {3/3.5) Bright & airy, canal Iron! home. Totally »novat§d. 2mm 464B Buck Key FW. $649,000 San!b@i. -

Miami Ink : Marked for Greatness Pdf, Epub, Ebook

MIAMI INK : MARKED FOR GREATNESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Wagenvoord | 160 pages | 14 Nov 2006 | TLC Publishing (VA) | 9780696232237 | English | United States Miami Ink : Marked for Greatness PDF Book Executive Director, Design: Matt Strelecki. Samantha rated it really liked it Sep 17, View our other privacy controls. For Consumers The sites and apps you use work with online advertising companies to provide you with advertising that is as relevant and useful as possible. Sign in for more lists. While it might not be entirely fair to call it a publicity stunt since the profits went to charity, it was nonetheless a clever bit of marketing when Kat decided to try and set the world record for most tattoos given in a hour period and have it chronicled on LA Ink. If James is to be believed, Kat was neither professional nor mature about the ending of their association together. Gayle Nix Jackson rated it it was amazing Feb 24, But some of the names drew criticism, starting with "Celebutard," which beauty store chain Sephora pulled from its shelves following huge backlash. They communicate important aspects of our lives: the country we live in and the religion we follow. It's also entirely possible that some simply chose to remain strictly tattoo artists rather than "celebrities. Self 11 episodes, This is a complete wooden chess set. Personalization may be informed by various factors such as the content of the site or app you are using, information you provide, historical searches you conduct, what your friends or contacts recommend to you, apps on your device, or based on your other interests. -

This Thesis Has Been Approved by the Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Art History

This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Art History __________________________ Dr. Jennie Klein, Art History Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Jennie Klein, Director of Studies, Art History ___________________________ Dr. Donal Skinner Dean, Honors Tutorial College SHE INKED! WOMEN IN AMERICAN TATTOO CULTURE ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University _______________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Art History ______________________________________ by Jessica Xiao Jin Long May 2020 ABSTRACT In my thesis, I trace the niche that women have created for themselves in the tattoo community, with a focus on the United States. I discuss the relationship between increasing visibility for women in the tattoo industry and the shift in women’s status in American culture. My study concludes with contemporary tattooed women, including prominent female tattoo artists, collectors, and media personalities. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: TATTOOS AND THE WOMEN WHO WEAR THEM 1-2 LITERATURE REVIEW 3-12 CH 1. FOUNDING FEMALES: THE TATTOOED LADIES 13-41 DIME MUSEUMS 15-18 THE FIRST TATTOOED LADIES 19-27 SELF-MADE FREAKS 27-30 THE CARNIVAL FREAK SHOW 30-34 NEW TATTOOED WOMEN 34-38 CONTINUING INFLUENCES 38-40 CH 2. FEMINISM AND RENAISSANCE 42-77 VIOLENCE AND MASCULINITY 46-52 TECHNICAL TRANSFORMATIONS 52-57 TATTOOS AS FINE ART 57-61 CELEBRITIES AND COUNTERCULTURE 61-64 THE SECOND WAVE 64-69 TATTOOING FEMINISM 69-74 CH 3. MIDDLE CLASS ACCEPTANCE & MASS COMMODIFICATION 78-119 PUNK TRIBALISM 80-86 END OF THE CENTURY ARTISTS 86-88 MIDDLE CLASS ACCEPTANCE 89-94 TATTOO MAGAZINES 95-97 MODERN PRIMITIVES 98-103 MAGAZINE MADNESS & INKED COVER GIRLS 103-107 TATTOOS ON TV 107-112 SEXUALITY AND STARDOM 112-116 CH 4. -

Highlight Der Woche: American Chopper Zwei Gegen Einen Montag 19.12.2011 Um 22:15 Uhr Auf DMAX DMAX Programm Programmwoche 51, 1

DMAX Programm Programmwoche 51, 17.12. bis 23.12.2011 Highlight der Woche: American Chopper Zwei gegen Einen Montag 19.12.2011 um 22:15 Uhr auf DMAX Neue Staffel, keine Annäherung: die Beziehung zwischen den Sprößlingen und dem Senior sind weiter unterkühlt. Besserung ist derzeit nicht in Sicht... Oder kommt es doch noch zur Aussöhnung in der Teutul-Family? Junior gegen Senior: Schauber-Sohn Paulie hat aus den ewigen Streitereien mit seinem alten Herren Konsequenzen gezogen: Der Junior betreibt nun erfolgreich seine eigene Chopper-Schmiede. Zusammen mit seinem Mechaniker-Team macht er seinem Vater kräftig Konkurrenz. Familien- Eintracht Fehlanzeige! Stattdessen geistert nur eine Frage durch die Werkstatt: Wer baut den heißeren Feuerstuhl? Oder kommen die schnauzbärtigen Streithähne am Ende doch auf einen gemeinsamen Nenner? Aktuell sieht es nicht danach aus: Bei der kleinsten Annäherung kracht es im Gebälk. Diplomatie war eben noch nie die Stärke der Teutuls. Den Bikes hat das bis dato aber nicht geschadet - die sind nach wie vor absolute Extraklasse! Paulie und sein Dad reden kein Wort miteinander. Stattdessen versuchen sich ihre Teams gegenseitig beim Bau legendärer Motorräder zu übertreffen – in getrennten Werkstätten versteht sich. Die Mechaniker von OCC entwerfen in dieser Episode ein Trike für den Familienbetrieb „Beck’s“, und auch die Truppe des Juniors hat einen lukrativen Auftrag an Land gezogen. Die Jungs schrauben an einem Bike für das Medizin- Unternehmen „Cepheid“. Da die Fronten mit Paulie noch immer verhärtet sind, versucht der Senior zumindest den Kontakt zu seinem anderen Sohn Mikey wiederherzustellen. Als dieser auf die Bemühungen des Vaters zurückhaltend reagiert, hat Teutul Senior sofort eine Erklärung parat: Da steckt garantiert sein Bruder dahinter! DMAX Programm Programmwoche 51, 17.12. -

The New Tattooed Lady: a Social and Sexual Analysis of Kat Von D and Megan Massacre by Anni Irish

MP: An Online Feminist Journal Summer 2013: Vol.4, Issue 2 The New Tattooed Lady: A Social and Sexual Analysis of Kat Von D and Megan Massacre by Anni Irish Tattooing, a body adornment practice that has become popular in contemporary culture, has a very fraught social history in the United States. This is especially true of the heavily tattooed female body, which has heretofore existed in marginal subcultures like freak shows and circuses; however it is the current representation of this body that I will explore in this paper. Reality television shows such as the TLC Network’s LA Ink and NY Ink, which take place in tattoo shops, have had a profound effect in shaping contemporary attitudes about tattooing and the people who engage in this subculture. As Margot Mifflin notes in the third edition of her book Bodies of Subversion: The Secret History of Women and Tattoo: “Reality TV shows brought tattooing into middle class living rooms and showcased many quality women artists starting with the game changing Kat Von D” (101). However, these shows have also assisted in the fetishization of the heavily tattooed body. Kat Von D, an internationally known tattoo artist and star of LA Ink, has become the modern day equivalent of the tattooed lady. While Von D has branded herself through the show and has developed her own line of products from it, there is a specific way in which her body is perceived. Like Von D, Megan Massacre is a tattoo artist and reality television star, on the TLC show NY Ink. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Miami Ink TATTOO TELEVISION

Tattoo Television: A Rhetorical Analysis of Miami Ink TATTOO TELEVISION: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF MIAMI INK VIA NARRATIVE PARADIGM THEORY Joseph Robert Nicola Abstract We are witness to a dramatic shift in cultural acceptance of tattoos. The first American Television program on tattoos, Miami Ink, is a distinct and substantial marker reflecting this current cultural shift in tattoo acceptance. Studying the narrative themes within Miami Ink can then serve as a reflection of cultural views when it first aired. Specifically, this analysis will examine the themes presented in the show and what they accomplish in terms of meaning. Keywords: tattoo, television, stigma, stereotypes, narrative paradigm theory Originally published in The Online Journal of Communication and Media: Volume 4 Issue 1, January 2018 Tattoo Television: A Rhetorical Analysis of Miami Ink 2 The TLC network reality series, Miami Ink, is the first American reality television series about a tattoo parlor, and the first show completely devoted to tattoos (Hibberd, 2005)1. The show closely follows four tattoo artists’ journey into starting a tattoo studio and the clientele they tattoo in South Beach, Florida. The tattoo artists engage each client in conversation as to their personal reasons for getting a tattoo. In addition, the show highlights the intricate and inspiring tattoos the artists create on their clients. Miami Ink was first broadcast on television in 2005 and ran till 2008 (Saraiya, 2014). The show is in syndication and continues to air worldwide ('Miami Ink' Comes to Fuse on Sunday, 2015; Tattoodo, 2015, 2014; Thobo-Carlsen & Chateaubriand, 2014). Miami Ink averaged 1.2 million viewers during its first season on the TLC network (Azote, 2005; Crupi, 2005). -

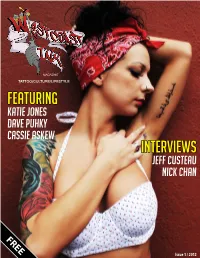

Featuring Interviews

MAGAZINE TATTOO/CULTURE/LIFESTYLE Featuring Katie Jones Dave Puhky Cassie Askew Interviews Jeff Custeau Nick Chan FREE Issue 1 / 2012 06 04 24 index. West Coast Ink is a tattoo and culture magazine established in Victoria, BC. Created by owner Ryan Bishop, the magazine has been developed to showcase the incredibly talented tattoo community on the west coast. From tattoo artists, to shops, to models and more, West Coast Ink Magazine has your daily fix to everything tattoo... Cassandra Cassie Askew 04 Over 60% of her body is covered in tattoos. 12 Why? Read Cassandra’s inspiring story to find out. Jeff Custeau 06 Our exclusive interview with the tattoo removal guy. He’s talented, funny, and he’s got some great stories. Jamie Miles Katie Jones 10 Full time truck drive, Jamie tells us his 18 passion for tattoos started before he could remember. Duncan Polson 16 Funny and sexy? You better believe it! This stand-up comedian gets personal. Nick Chan Dave Puhky 24 Tattoo artist Nick Chan tells us about his 26 grind to success. Tips from Beyond the INK 30 Getting your first tattoo? Read our tips on “How to Interact with a Tattoo Artist”. 2 | West Coast Ink | Issue 1 Issue 1 | West Coast Ink | 3 Cassandra MORGAN Photographer : Julia Loglisci They say only the strong survive in this life; for Cassandra Morgan, this is an understatement. Those who know Cassandra might say that she’s been through hell and back, but her amazing strength and charisma allow her to live each day to its fullest.