Tattooed Body”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday Morning, March 15

THURSDAY MORNING, MARCH 15 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Donald Sutherland; Live! With Kelly Ashley Judd; 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) John Ramsey. (N) (cc) (TV14) Whitney Cummings. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) 9:10 2012 NCAA Basketball Tournament Second Round. (N) (Live) (cc) 2012 NCAA Tour- 6/KOIN 6 6 nament NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Drugstore products; Joel McHale. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Sit and Be Fit Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Letter ‘R’ Mystery. Remember the Ladies Activities of Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Things turn up missing. (TVY) early American women. (TVG) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Former 12/KPTV 12 12 child star is murdered. (TV14) Portland Public Affairs Paid Paid Jane and the Willa’s Wild Life Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Dragon (TVY) (TVY7) Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Dean & Mary Life Change Cafe John Bishop TV Behind the Lifestyle Maga- Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) Brown Scenes (cc) zine (cc) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show How Did 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass This Baby Get Injured? (TV14) Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show Parents and America Now (cc) Divorce Court Excused (cc) Excused (cc) Cheaters (cc) Cheaters (cc) America’s Court Judge Alex (cc) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack offspring at war. -

2017 Tattoo Hebrew

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 7 – Issue: 3 July - 2017 Tattoo Hebrew: An Analysis of Miami Ink’s Presentation of Jewish Tattoo Themes Joseph Robert Nicola, Century College, Minnesota, U.S.A Abstract Tattoos are growing in popularity among people of the Jewish faith. The following analysis examines the Jewish tattoo narrativespresented in the first American television program about tattooing, Miami Ink. Narrative Paradigm Theory is utilized to explore specific Jewish tattoo themes communicated. Keywords: Jewish, tattoo, television, stigma, narrative paradigm © Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies 146 Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 7 – Issue: 3 July - 2017 The TLC network reality series, Miami Ink, follows four tattoo artists and the clientele they tattoo in South Beach, Florida. Miami Ink is the first American reality television series about a tattoo parlor, and the first show completely devoted to tattoos (Hibberd, 2005; Oldenburg, 2005). Miami Inkoriginally ran from 2005 to 2008 (Saraiya, 2014). The show continues to air in syndication worldwide in over 160 countries (Tattoodo, 2015, 2014; Thobo-Carlsen & Chateaubriand, 2014). Relevance for Studying the Topic Research into the growing popularity of tattoos in America has attributed this rise of acceptance to open communication from the tattoo industry and positive media exposure of tattoos (DeMello, 2000; Wyatt, 2003; Yamada, 2009). With these media influences helping advance the popularity of tattoos, it is then relevant to look closely at the first television show dedicated specifically to tattooing. This analysis will examine the Jewish tattoo themes presented in the show and what they accomplish in terms of meaning. -

Tuesday Morning, May 8

TUESDAY MORNING, MAY 8 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Ricky Martin; Giada De Live! With Kelly Stephen Colbert; 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Laurentiis. (N) (cc) (TV14) Miss USA contestants. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Martin Sheen and Emilio Estevez. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Sit and Be Fit Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Rhyming Block. Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Three new nursery rhymes. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Iden- 12/KPTV 12 12 tity Crisis. (cc) (TV14) Positive Living Public Affairs Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Billy Graham Classic Crusades Doctor to Doctor Behind the It’s Supernatural Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (cc) Scenes (cc) (TVG) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (N) (cc) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass (TV14) Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (N) (cc) America Now (N) Paid Cheaters (cc) Divorce Court (N) The People’s Court (cc) (TVPG) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVPG) (cc) (TVG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Hunter A fugitive and Criminal Minds The team must Criminal Minds Hotch has a hard CSI: Miami Inside Out. -

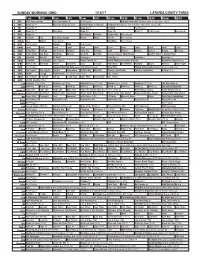

Sunday Morning Grid 1/15/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/15/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Football Night in America Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Kansas City Chiefs. (10:05) (N) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Program Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Planet Weird DIY Sci Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Miranda Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Escape From New York ››› (1981) Kurt Russell. -

FIRA's Secret Sauce

Inside: Seacoast Holidays ALSO INSIDE: TV LIstINGS 40,000 COPIES Please Deliver Before FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 2006 Vol. 32 | No. 46 | 2 Sections |40 Pages FIRA’s Secret Sauce Non-profit association is pure protein for 30-plus local independent restaurants, providing value-laden consumer promotions while fortifying their purchasing power BY MICHAEL P. CONNELLY OWNER & PUBLISHER Cyan ATLANTIC NEWS t has become commonplace, chain Magenta restaurants are popping up instantly Iall around us. You probably didn’t notice this alarming trend as they navigate through the town Yellow zoning and planning process on the Sea- coast, but you can’t mistake their arrival during the construction phase as you travel Black the area. You see the balloons and the hoopla once they’ve opened. It’s at that moment in the blink of an eye when you see the competitive landscape change forever for the many longstanding locally owned restaurants. Today it’s a TGI Fridays, tomorrow a Chili’s, Applebee’s, or Pizzeria UNO. And it’s growing. Suddenly we’ve become “Californian- ized,” losing our New England flavor. FIRA Continued on 26A• The Perfect Gift! Voted World’s Best For Families 6 Years In A Row at The World Travel Awards One Gift Card Beaches is the ultimate family getaway that Welcomed at more than 30 includes non-stop fun with refined luxury. of the Area’s Favorite Restaurants All inclusive highlights: • Four family resorts located on SAVE 2 exotic islands. UP TO Give & Receive! • MULTI-CHOICE GOURMET DINING at up to 10 restaurants. % Limited Time Offer: Purchase a • Supervised KIDS KAMP. -

Tv Pg 5 12-11.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, December 11, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle FUN BY THE NUM B ERS will have you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, column and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESD A Y ’S TUESDAY EVENING DECEMBER 11, 2007 WEDNESDAY EVENING DECEMBER 12, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone CSI: Miami: Burned CSI: Miami: Kill Switch The Sopranos Mob boss deals with Paranormal CSI: Miami: Burned CSI: Miami: Bloodline CSI: Miami: Rush (TV14) CSI: Miami: Just Mur- Paranormal Paranormal CSI: Miami: Bloodline 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E (TV14) (HD) (HD) dered (TV14) (HD) (R) (HD) (R) (HD) (TV14) (HD) (TV14) (HD) (TV14) (HD) family issues. (TV14) (HD) (R) (HD) (TV14) (HD) Pushing Daisies: Private Practice (TV14) (:02) Dirty Sexy Money: Pilot KAKE News Nightline (N) (:01) Jimmy Kimmel Live Shrek Halls (:32) Pooh According Jim According Jim Boston Legal: No Brains Left KAKE News Nightline (N) (:01) Jimmy Kimmel Live 46 ABC 46 ABC (HD) (TVY) (R) (R) Behind (HD) at 10 (TV14) Corpsicle (N) (HD) (R) (HD) (TVPG) (R) (HD) at 10 (TV14) Anaconda Adventure Alligators American alli- Animal Precinct: Cases of Big Cat Diary: Battle for Anaconda Adventure Growing Up .. -

OUR GUARANTEE You Must Be Satisfied with Any Item Purchased from This Catalog Or Return It Within 60 Days for a Full Refund

Edward R. Hamilton Bookseller Company • Falls Village, Connecticut February 26, 2016 These items are in limited supply and at these prices may sell out fast. DVD 1836234 ANCIENT 7623992 GIRL, MAKE YOUR MONEY 6545157 BERNSTEIN’S PROPHETS/JESUS’ SILENT GROW! A Sister’s Guide to ORCHESTRAL MUSIC: An Owner’s YEARS. Encounters with the Protecting Your Future and Enriching Manual. By David Hurwitz. In this Unexplained takes viewers on a journey Your Life. By G. Bridgforth & G. listener’s guide, and in conjunction through the greatest religious mysteries Perry-Mason. Delivers sister-to-sister with the accompanying 17-track audio of the ages. This set includes two advice on how to master the stock CD, Hurwitz presents all of Leonard investigations: Could Ancient Prophets market, grow your income, and start Bernstein’s significant concert works See the Future? and Jesus’ Silent Years: investing in your biggest asset—you. in a detailed but approachable way. Where Was Jesus All Those Years? 88 Book Club Edition. 244 pages. 131 pages. Amadeus. Paperbound. minutes SOLDon two DVDs. TLN. OU $7.95T Broadway. Orig. Pub. at $19.95 $2.95 Pub. at $24.99SOLD OU $2.95T 2719711 THE ECSTASY OF DEFEAT: 756810X YOUR INCREDIBLE CAT: 6410421 THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF Sports Reporting at Its Finest by the Understanding the Secret Powers ANTARCTIC JOURNEYS. Ed. by Jon Editors of The Onion. From painfully of Your Pet. By David Greene. E. Lewis. Collects a heart-pounding obvious steroid revelations to superstars Interweaves scientific studies, history, assortment of 32 true, first-hand who announce trades in over-the-top TV mythology, and the claims of accounts of death-defying expeditions specials, the world of sports often seems cat-owners and concludes that cats in the earth’s southernmost wilderness. -

NAKUL DEV MAHAJAN NDM Bollywood Dance Productions and Studios Inc

NAKUL DEV MAHAJAN NDM Bollywood Dance Productions and Studios Inc. 17711 S. Pioneer Blvd, Artesia CA Business: 562.402.7761 / www.ndmdance.com / [email protected] Representation and Management Shelli Margheritis | [email protected] JC Gutierrez | [email protected] O: (310)955-1082 | C: (310) 606-0854 Nakul Dev Mahajan, an American Bollywood choreographer and dancer and is best known best for his work on “So You Think You Can Dance.” A pioneering artist, he opened the premier Bollywood Dance School in the USA, enriching over 3000 students a year. Nakul’s 25 years of experience and longevity has labeled him as “Hollywood’s Favorite Bollywood Choreographer. Some of his other major accomplishments include Disney, A.R. Rahman Jai Ho World Tour, Miss America and bringing Bollywood to the White House with Michelle Obama. Choreography and Appearances Television/Movies FOX- So You Think You Can Dance: Seasons 4-16 - Nigel Lythgoe, Simon Fuller Creators Disney Junior - Mira, Royal Detective: Seasons 1-2 - Sascha Paladino Executive Producer Disney Junior - Mickey Mouse Mixed-Up Adventures: A Gollywood Wedding! – Dir. by Phil Weinstein Disney Junior - Mickey Mouse Mixed-Up Adventures: No Dilly Dally in New Delhi- Dir. by Broni Likomanov Netflix - Fuller House - Directed by Katy Garretson CBS - The World’s Best - Judge - Mark Burnett and Mike Darnell Executive Producers NBC - The Office -Directed by Miguel Arteta NBC - Passions - Directed by Phideaux Xavier NBC - Never mind Nirvana (pilot) - Directed by David Schwimmer NBC -

This Is My Tattoo,” Intersections 11, No

intersections online Volume 11, Number 1 (Summer 2010) Matthew Hayes, “This is My Tattoo,” intersections 11, no. 1 (2010): 127-163. ABSTRACT What does it mean to own a tattoo? How does the tension between running a business and creating art affect the experience of producing and receiving a tattoo? This project consists of two parts: a written paper and a short documentary film. Based on original research, I explore what ownership means to tattoo artists and tattooed persons, and how this idea of ownership may or may not change when a tattoo is transmitted to film. Several participants conclude that the person who wears the tattoo ultimately owns the tattoo, while others believe all those involved in the experience have a stake in the ownership of their tattoo. While my conclusions are decidedly incomplete, partly a result of the originality of this work, I nevertheless draw attention to the significance of this tension to the way one looks at his or her tattoo after it is completed. I also explore in depth the complexities of using film as a research tool, as well as of conducting “field work” at home. http://depts.washington.edu/chid/intersections_Summer_2010/Matthew_Hayes_This_Is_My_Tattoo.pdf Video component of “This is My Tattoo”: http://vimeo.com/10670029 © 2010 Matthew Hayes, intersections. 126 Matthew Hayes This is My Tattoo 127 intersections Summer 2010 This is My Tattoo By Matthew Hayes1 Trent University, Ontario everal years ago I was slowly pacing the lobby of a tattoo studio in Toronto, S nervously anticipating the experience to come. While it was not my first, the tattoo that I was waiting to have applied on my skin was my largest to date, and it was going straight on my ribs, one of the most painful areas of the body to have tattooed (or so they say). -

Ny Ink Season 4 Premiere

Ny ink season 4 premiere Season, Episodes, Season Premiere, Season Finale. 1, 8, June 2, (), July 21, (). 2, 10, December 29, No. of seasons: 3. Documentary · Ami James, a breakout from Miami Ink, will open a new shop, Wooster Street "The Walking Dead" Cast Tease Season 8 · IMDb on the Scene 10 August AM, | Variety - TV News · Cgm interviews Megan Missing: premiere. –AMERICA'S WORST TATTOOS & NY INK premiere Thursday, April 4 at 9 meet tattoo mistakes on Thursday, April 4 with the series premiere of TLC's AMERICA'S WORST TATTOOS and season three premiere of NY INK. NY Ink Official Site. Watch Full Episodes, Get Behind the Scenes, Meet the Cast, and much more. Stream NY Ink FREE with Your TV Subscription!Missing: premiere. Ink. M likes. Welcome to the Official Facebook page for TLC's NY Ink! Change of season is approaching -- maybe some new ink is in your future!? LA Ink. New Season of VH1's BLACK INK CREW to Premiere 8/24 engagement to Ceaser, but Ceaser struggles with the idea of leaving New York. OFFICIAL WEBSITE. Watch the full episode online. After leaving Black Ink closed for a month, Ceaser is back in Harlem. In North Carolina. Black Ink Crew | Official Season 4 Super Trailer | Premieres April 4th + a lot of surprises in store for us from. In the Season 4 premiere, Ceaser reopens Black Ink after it's been closed for a Dutchess spends her last days in New York City attempting to make amends. Our favorite crew of black New York tattoo artists have returned for a fourth In the Season 4 premiere. -

15 Août 2007 1,25$ + T.P.S

Le verbe aimer est le plus com- FESTIVAL D’ÉTÉ pliqué de la langue. Son passé DU n’est jamais simple, son présent CENTRE-VILLE n’est qu’imparfait et son futur HA11-HA12-HA13 toujours conditionnel. Jean Cocteau Vol. 32 No.22 Hearst On ~ Le mercredi 15 août 2007 1,25$ + T.P.S. Plantation expérimentale Un premier Noël des campeurs Semaine décisive Portant leurs vêtements Hawaïens, Danica et Marie-Mai Lacroix ont participé à leur premier Noël des campeurs samedi dernier chez à la balle lente Veilleux Camping & Marina. Par une température idéale, l’événement a connu un beau succès. Photo Le Nord/CP HA23 Mercredi Jeudi Vendredi Samedi Dimanche Lundi Ensoleillé avec Nuageux Ciel variable passages nuageux avec éclaircies Nuageux avec averses Ensoleillé Faible pluie Max 14 Min 7 Max 18 Min 6 Max 20 Min 9 Max 21 Min 12 Max 12 Max 15 Min 10 PdP 20% PdP 70% PdP 20% PdP 60% PdP 0% PdP 70% Achat du Centre Chevaliers de Colomb Le Conseil des Arts obtient l’appui de la municipalité HEARST (FB) – Le Conseil des Cet appui a été donné à la «Cet appui était nécessaire directrice générale du Conseil des d’avoir une meilleure vue lors Arts de Hearst a reçu l’appui de suite d’une rencontre tenue pour nous permettre de soumettre Arts, Lina Payeur. des spectacles. On prévoit égale- la municipalité dans son projet récemment entre des représen- le projet d’ici la fin août à notre Celle-ci indique que les négo- ment une scène au niveau du d’acquisition et de rénovation du tants du Conseil des Arts et du principal bailleur de fonds, ciations entre le Conseil des Arts plancher. -

THE READY SET Sean Bello Jason Witzigreuter Gets Bamboozled

March 24-30, 2010 \ Volume 20 \ Issue 12 \ Always Free Film | Music | Culture SPRING’S HIGH NOTES Concerts and CDs not to Pass Over She & Him and More! ©2010 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 988-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM • ONE FREE COPY PER PERSON Join CAMPUS CIRCLE www.campuscircle.com Saturday Are You Being Treated + Fitness March 27, 2010 for Bipolar Disorder? 11:00am to 4:00pm Do You Have Mood Swings? Music Center Plaza Are You Still Struggling with Depression? If you: n Are between the ages of 18 and 75 n Are diagnosed with bipolar disorder and are regularly suffering from depression n Are currently taking either Lithium or Divalproex (Depakote) to treat your bipolar disorder You may qualify for a research study that compares Lurasidone (an investigational drug) to placebo (an inactive substance) in treating bipolar depression. Compensation is up to $900 for participating in eight visits over seven weeks. Study completers may be eligible to continue in a 24-week extension study that includes six visits with $720 in additional compensation. Study participants will receive study medication and a medical evaluation at no cost, along with reimbursement for study-related expenses. For more information, please call Explore how dance has taken 1-888-CEDARS-3 the fitness world by storm. or visit us at Learn new moves and taste test a variety of dance fitness stlyes. NO EXPERIENCE NECESSARY. www.cedars-sinai.edu/psychresearch $1 per lesson. More info: musiccenter.org IRB No: Pro17928 UCR Summer Sessions 2010 About an hour away with easy parking! Easy one-page application online.