Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Plants Which Support Insects

Native Meadow Plants for Butterflies, Moths and Other Insects Dry Meadow Perennials Agastache foeniculum (Anise hyssop) Allium cernuum (Nodding onion) Antennaria spp. (Pussy-toes) Aquilegia canadensis (Columbine) Aruncus dioicus (Goats beard) Asclepias spp. (Milkweed) Ionactis linariifolia (Flax-leaf white top aster) Baptisia tinctoria (Yellow wild indigo) Callirhoe spp. (Poppy mallow) Campanula rotundifolia (Thread-leaf bellflower) Chrysopsis villosa (Golden hairy aster) Coreopsis verticillata (Tickseed) Dicentra spp. (Bleeding heart) Echinacea spp. (Coneflower) Eryngium yuccifolium (False Yucca) Geranium maculatum (Wild geranium) Helianthus mollis (Sunflower) Heliopsis helianthoides (Oxeye) Lupinus perennis (Sundial lupine) Monarda punctata (Horsemint) Opuntia humifusa (Eastern prickly pear) Penstemon digitalis (Foxglove beardtongue) Pycnanthemum tenuifolium (Narrow leaf mountain mint) Ratibida spp. (Mexican hat) Rudbeckia spp. (Black-eyed Susan) Solidago spp. (Goldenrod) Vernonia letermannii (Ironweed) Viola pedata (Birds foot violet) Courtesy of Dan Jaffe Propagator and Stock Bed Grower New England Wild Flower Society [email protected] Native Meadow Plants for Butterflies, Moths and Other Insects Moist Meadow Perennials Amsonia spp. (Blue star) Asclepias incarnata (Swamp milkweed) Boltonia asteroides (False aster) Chelone glabra (White turtlehead) Conradina verticillata (False rosemary) Eutrochium spp. (Joe-Pye weed) Filipendula rubra (Queen of the prairie) Gentiana clausa (Bottle gentian) Liatris novae-angliae (New England -

Open As a Single Document

Cercis: The Redbuds by KENNETH R. ROBERTSON One of the few woody plants native to eastern North America that is widely planted as an ornamental is the eastern redbud, Cercis canadensis. This plant belongs to a genus of about eight species that is of interest to plant geographers because of its occurrence in four widely separated areas - the eastern United States southwestward to Mexico; western North America; south- ern and eastern Europe and western Asia; and eastern Asia. Cercis is a very distinctive genus in the Caesalpinia subfamily of the legume family (Leguminosae subfamily Caesalpinioi- - deae). Because the apparently simple heart-shaped leaves are actually derived from the fusion of two leaflets of an evenly pinnately compound leaf, Cercis is thought to be related to -~auhinic~, which includes the so-called orchid-trees c$~~ cultivated in tropical regions. The leaves of Bauhinia are usu- ally two-lobed with an apical notch and are made up of clearly ~ two partly fused leaflets. The eastern redbud is more important in the garden than most other spring flowering trees because the flower buds, as well as the open flowers, are colorful, and the total ornamental season continues for two to three weeks. In winter a small bud is found just above each of the leaf scars that occur along the twigs of the previous year’s growth; there are also clusters of winter buds on older branches and on the tree trunks (Figure 3). In early spring these winter buds enlarge (with the excep- tion of those at the tips of the branches) and soon open to re- veal clusters of flower buds. -

Post-Wildfire Response of Shasta Snow-Wreath

California Fish and Wildlife, Fire Special Issue; 92-98; 2020 RESEARCH NOTE Post-wildfire response of Shasta snow-wreath LEN LINDSTRAND III1*, JULIE A. KIERSTEAD2, AND DEAN W. TAYLOR3 † 1Sierra Pacific Industries,P .O. Box 496014, Redding, CA 96049-6014, USA 2P. O. Box 491536, Redding CA, 96049, USA 33212 Redwood Drive, Aptos, CA, 95003, USA † Deceased *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Key words: Hirz fire, Neviusia cliftonii, post-wildfire response, Shasta snow-wreath, vegetative reproduction __________________________________________________________________________ Shasta snow-wreath (Neviusia cliftonii) is a rare shrub of the Rosaceae: tribe Kerrieae endemic to the southeastern Klamath Mountains in the general vicinity of Shasta Lake, Shasta County, California. The species was discovered less than 30 years ago (Shevock et al. 1992; Taylor 1993) and initially considered a limestone obligate. Subsequent occurrences have also been found on various non-limestone substrates (Lindstrand and Nelson 2005a, b, 2006; DeWoody et al. 2012; Jules et al. 2017). The only congener, Alabama snow-wreath (Neviusia alabamensis), also has a limited range restricted to several disjunct populations in the southeastern United States and occurs on limestone and non-limestone sedimentary substrates (Long 1989; Freiley 1994). Shasta snow-wreath is deciduous and produces flowers with showy white stamens, five toothed green sepals, and rarely, one to three narrow white petals. Based on our observations since its discovery, the species reproduces vegetatively, forming thickets of stems from the root system. Despite observations of developing achenes, no viable seed nor seedlings have been collected or observed. We are not aware of any pollinators and the blooms lack detect- able scent. -

INDEX for 2011 HERBALPEDIA Abelmoschus Moschatus—Ambrette Seed Abies Alba—Fir, Silver Abies Balsamea—Fir, Balsam Abies

INDEX FOR 2011 HERBALPEDIA Acer palmatum—Maple, Japanese Acer pensylvanicum- Moosewood Acer rubrum—Maple, Red Abelmoschus moschatus—Ambrette seed Acer saccharinum—Maple, Silver Abies alba—Fir, Silver Acer spicatum—Maple, Mountain Abies balsamea—Fir, Balsam Acer tataricum—Maple, Tatarian Abies cephalonica—Fir, Greek Achillea ageratum—Yarrow, Sweet Abies fraseri—Fir, Fraser Achillea coarctata—Yarrow, Yellow Abies magnifica—Fir, California Red Achillea millefolium--Yarrow Abies mariana – Spruce, Black Achillea erba-rotta moschata—Yarrow, Musk Abies religiosa—Fir, Sacred Achillea moschata—Yarrow, Musk Abies sachalinensis—Fir, Japanese Achillea ptarmica - Sneezewort Abies spectabilis—Fir, Himalayan Achyranthes aspera—Devil’s Horsewhip Abronia fragrans – Sand Verbena Achyranthes bidentata-- Huai Niu Xi Abronia latifolia –Sand Verbena, Yellow Achyrocline satureoides--Macela Abrus precatorius--Jequirity Acinos alpinus – Calamint, Mountain Abutilon indicum----Mallow, Indian Acinos arvensis – Basil Thyme Abutilon trisulcatum- Mallow, Anglestem Aconitum carmichaeli—Monkshood, Azure Indian Aconitum delphinifolium—Monkshood, Acacia aneura--Mulga Larkspur Leaf Acacia arabica—Acacia Bark Aconitum falconeri—Aconite, Indian Acacia armata –Kangaroo Thorn Aconitum heterophyllum—Indian Atees Acacia catechu—Black Catechu Aconitum napellus—Aconite Acacia caven –Roman Cassie Aconitum uncinatum - Monkshood Acacia cornigera--Cockspur Aconitum vulparia - Wolfsbane Acacia dealbata--Mimosa Acorus americanus--Calamus Acacia decurrens—Acacia Bark Acorus calamus--Calamus -

Bulletin Winter 2002 Volume 48 Number 4

BULLETIN WINTER 2002 VOLUME 48 NUMBER 4 Sarah P. Duke Gardens..................................................................................................................126 News from the Society Bill Dahl, Executive Director............................................................................................130 News from the Sections P Archives and History Section..........................................................................................130 Personalia Darbaker Prize, Dr. Arthur Grossman...........................................................................131 2002 Lawrence Memorial Award, Andrew L. Hipp.....................................................131 Plowman Research Award, Pedro Lezama Asencio................................................131 Courses/Workshops Highlands Biological Station Course Offerings in 2003...........................................132 Symposia, Conferences, Meetings Deep Achene: The Compositae Alliance First International Meeting, South Africa........................................................................................................133 Illinois Symposium on Invasive Species.....................................................................135 Second International Elm Conference.........................................................................135 4th International Plant Biomechanics Conference....................................................135 International Solanaceae Conference and Poster Photo Competition.................136 Other News Plant Group -

Invade the Southeast by Nancy Fraley, National Park Service

National Park Service Exotic Plant Management Teams Invade the Southeast by Nancy Fraley, National Park Service odeled after the approach used M in wildland fire fighting, Exotic Plant Management Teams (EPMTs) provide highly trained, mobile strike forces of plant management specialists to assist national park units in the control of invasive, exot- ic plants. Each Exotic Plant Management Team employs the expertise of local experts and the capabilities of local agen- cies. Each sets its own work priorities based on the following factors: severity of threat to high-quality natural areas and rare species; extent of targeted infestation; probability of successful control and potential for restoration; opportunities for public involvement; and park commitment to follow-up monitoring and treatment. In the southeastern United States, 40 nation- al park units now can call upon the resources of an EPMT. The success of this initiative derives, in part, from the ability of these teams to adapt to the needs and conditions of the individual parks they serve. As of January 2004, the National Park Service (NPS) has established three EPMTs in the southeastern US. Nationwide there are 17 EPMTs serving national park units. These teams are funded through the NPS Natural Resource Challenge, a multidisci- plinary five-year program established in 1999 to strengthen natural resource man- agement within the national park system. The teams represent a formidable tool for invasive, exotic plant control and play an integral role in reaching the goals identi- fied in the NPS Natural Resource Challenge. Today, exotic plants infest some 2.6 million acres in the National Park System, reducing the natural diversity of these great places. -

Threatened and Endangered Species List

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum -

Prsrt Std U.S. Postage PAID Gainesville, FL Permit No

Prsrt std U.S. Postage PAID Gainesville, FL Permit No. 726 AL2004 FALL AL2004 FALL Wildland Weeds Wildland Wildland Weeds Wildland FLORIDA EXOTIC PEST PLANT COUNCIL Officers Editorial Brazilian Pepper Karen Brown Jim Cuda Jim Burney, Chair University of Florida Aquatic Vegetation Control, Inc. Education Entomology Department 561/845-5525 Leesa Souto 352/392-1901 Ext. 126 Wildland Weeds Wildland ALLWeedsOLUME UMBER [email protected] Midwest Research Institute F 2004, V 7, N 4 [email protected] 321/723-4547 Ext. 200 Dianne Owen, Secretary [email protected] Carrotwood Florida Atlantic University Chris Lockhart 954-236-1085 FNGA/FLEPPC Liaison Table of Contents [email protected] Doria Gordon Dioscorea University of Florida Mike Bodle 5 Air Potatoes Run Rampant Kristina Kay Serbesoff-King, The Nature Conservancy Treasurer Grasses by Karen Brown 352/392-5949 The Nature Conservancy Greg MacDonald [email protected] 6 Notes from the Lygodium Research Review Meeting 561-744-6668 University of Florida -and- [email protected] Agronomy Department by Jeff Hutchinson, Ken Langeland, and Amy Ferriter JB Miller 352/392-1811 Ext. 228 Karen Brown, Editor Florida Park Service [email protected] 9 Bureau of Invasive Plant Management University of Florida 904/794-5959 Lygodium Lygodium Strike Team Center for Aquatic [email protected] & Invasive Plants Amy Ferriter/Tom Fucigna 11 TN-EPPC Board of Directors Legislative 352/392-1799 Skunkvine Matthew King [email protected] Brian Nelson 12 TN-EPPC Turns 10! Local Arrangements Mike Bodle, SWFWMD -

Chapter 4 Native Plants for Landscape Use in Kentucky

Chapter 4 Native Plants for Landscape Use In Kentucky A publication of the Louisville Water Company Wellhead Protection Plan, Phase III Source Reduction Grant # X9-96479407-0 Chapter 4 Native Plants for Landscape Use in Kentucky Native Wildflowers and Ferns The U. S. Department of Transportation, (US DOT), has developed a listing of native plants, (ferns, annuals, perennials, shrubs, and trees), that may be used in landscaping in the State of Kentucky. Other agencies have also developed listings of native plants, which have been integrated into the list within this guidebook. While this list is, by no means, a complete report of the native species that may be found in Kentucky, it offers a starting point for additional research, should the homeowner wish to find additional KY native plants for use in a landscape design, or to check if a plant is native to the State. A reference book titled Wildflowers and Ferns of Kentucky, which was recommended by personnel at the Salato Wildlife Center as an excellent reference for native plants, was also used to develop the list. (A full bibliography is listed at the end of this chapter.) While many horticultural and botanical experts may dispute the inclusion of specific plants on the listing, or wish to add more plants, the list represents the latest information available for research, by the amateur, at the time. The information listed within the list was taken at face value, and no judgment calls were made about the suitability of plants for the list. The author makes no claims as to the completeness, accuracy, or timeliness of this list. -

Phylogenetic Relationships in Rosaceae Inferred from Chloroplast Matk and Trnl-Trnf Nucleotide Sequence Data

Plant Syst. Evol. 231: 77±89 32002) Phylogenetic relationships in Rosaceae inferred from chloroplast matK and trnL-trnF nucleotide sequence data D. Potter1, F. Gao1, P. Esteban Bortiri1, S.-H. Oh1, and S. Baggett2 1Department of Pomology, University of California, Davis, USA 2Ph.D. Program Biology, Lehman College, City University of New York, New York, USA Received February 27, 2001 Accepted October 11, 2001 Abstract. Phylogenetic relationships in Rosaceae economically important fruits of temperate were studied using parsimony analysis of nucleo- regions is produced by members of this family, tide sequence data from two regions of the including species of Malus 3apples), Pyrus chloroplast genome, the matK gene and the trnL- 3pears), Prunus 3plums, peaches, cherries, trnF region. As in a previously published phylog- almonds, and apricots), Rubus 3raspberries), eny of Rosaceae based upon rbcL sequences, and Fragaria 3strawberries). The family also monophyletic groups were resolved that corre- includes many ornamentals, e.g., species of spond, with some modi®cations, to subfamilies Maloideae and Rosoideae, but Spiraeoideae were Rosa 3roses), Potentilla 3cinquefoil), and polyphyletic. Three main lineages appear to have Sorbus 3mountain ash). A variety of growth diverged early in the evolution of the family: 1) habits, fruit types, and chromosome numbers Rosoideae sensu stricto, including taxa with a base is found within the family 3Robertson 1974), chromosome number of 7 3occasionally 8); 2) which is traditionally divided into four sub- actinorhizal Rosaceae, a group of taxa that engage families on the basis of fruit type 3e.g., Schulze- in symbiotic nitrogen ®xation; and 3) the rest of the Menz 1964). -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,973,216 B2 Espley Et Al

US007973216 B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,973,216 B2 Espley et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 5, 2011 (54) COMPOSITIONS AND METHODS FOR 6,037,522 A 3/2000 Dong et al. MODULATING PGMENT PRODUCTION IN 6,074,877 A 6/2000 DHalluin et al. 2004.0034.888 A1 2/2004 Liu et al. PLANTS FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (75) Inventors: Richard Espley, Auckland (NZ); Roger WO WOO1, 59 103 8, 2001 Hellens, Auckland (NZ); Andrew C. WO WO O2/OO894 1, 2002 WO WO O2/O55658 T 2002 Allan, Auckland (NZ) WO WOO3,0843.12 10, 2003 WO WO 2004/096994 11, 2004 (73) Assignee: The New Zealand Institute for Plant WO WO 2005/001050 1, 2005 and food Research Limited, Auckland (NZ) OTHER PUBLICATIONS Bovy et al. (Plant Cell, 14:2509-2526, Published 2002).* (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Wells (Biochemistry 29:8509-8517, 1990).* patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Guo et al. (PNAS, 101: 9205-9210, 2004).* U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. Keskinet al. (Protein Science, 13:1043-1055, 2004).* Thornton et al. (Nature structural Biology, structural genomics (21) Appl. No.: 12/065,251 supplement, Nov. 2000).* Ngo et al., (The Protein Folding Problem and Tertiary Structure (22) PCT Filed: Aug. 30, 2006 Prediction, K. Merz., and S. Le Grand (eds.) pp. 492-495, 1994).* Doerks et al., (TIG, 14:248-250, 1998).* (86). PCT No.: Smith et al. (Nature Biotechnology, 15:1222-1223, 1997).* Bork et al. (TIG, 12:425-427, 1996).* S371 (c)(1), Vom Endt et al. -

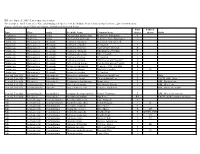

Alabama Inventory List

Alabama Inventory List The Rare, Threatened, & Endangered Plants & Animals of Alabama June 2004 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................................................................1 DEFINITION OF HERITAGE RANKS .................................................................................................................................3 DEFINITIONS OF FEDERAL & STATE LISTED SPECIES STATUS.............................................................................5 AMPHIBIANS............................................................................................................................................................................6 BIRDS .........................................................................................................................................................................................7 MAMMALS...............................................................................................................................................................................10 FISHES.....................................................................................................................................................................................12 REPTILES ................................................................................................................................................................................16 CLAMS & MUSSELS ..............................................................................................................................................................18