Ebo Landing: History, Myth, and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leading Manufacturers of the Deep South and Their Mill Towns During the Civil War Era

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2020 Dreams of Industrial Utopias: Leading Manufacturers of the Deep South and their Mill Towns during the Civil War Era Francis Michael Curran West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Curran, Francis Michael, "Dreams of Industrial Utopias: Leading Manufacturers of the Deep South and their Mill Towns during the Civil War Era" (2020). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7552. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7552 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dreams of Industrial Utopias: Leading Manufacturers of the Deep South and their Mill Towns during the Civil War Era Francis M. Curran Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Jason Phillips, Ph.D., Chair Brian Luskey, Ph.D. -

History of the Town of Darien, Georgia - Established 1736

History of the Town of Darien, Georgia - Established 1736 There are over 100 miles of pristine coastline, 400,000 acres of salt water marsh and 15 Barrier Islands that bring a uniqueness to Coastal Georgia that you will seldom find anywhere else in the world. The Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway which stretches from Key West to Boston, is connected to the local Altamaha River, which is the second largest fresh water discharge east of the Mississippi River. This charming coastal Georgia town sits just off of the mouth of the Altamaha River on the local deep-water docks of the Darien River. It is located just 25 miles from the prestigious shoreline of Sea Island, Georgia, one of the fastest growing luxury markets in the country and home to some of the country’s wealthiest … movie stars as well as professional athletes. FOUNDED BY SCOTTISH HIGHLANDERS ON JANURY 19, 1736 The town of Darien has a wealth of history dating back to the 1700’s. In October 1735, a band of Highland Scots, recruited from the vicinity of Inverness, Scotland, by Hugh Mackay and George Dunbar, sailed from Inverness, Scotland on the Prince of Wales. On January 19, 1736, General James Edward Oglethorpe founded the new Georgia colony of New Inverness, which later became known as Darien, Georgia. Located at the mouth of the Altamaha River, Fort King George was built in 1721 along what is now known as the Darien River and served as the southernmost outpost of the British Empire in the Americas until 1727. It is the oldest English fort remaining on the Georgia coast. -

Of Com!,Iissioners, Glynn Thursday, November 5, at 8

REGULAR MEETING, BOARD OF COM!,IISSIONERS,GLYNN COUNTY GEORGIA, HEID THURSDAY,NOVEMBER 5, L992, AT 8:30 A.M. PRESENT: Chairman Rev. E. C. Tillman Vice Chairman Robert H. Bob Boyne Commissioner William E. Dismer Commissioner Jack Hardman Commissioner Karen Moore Commissioner Joe Smith ABSENT: Commissioner W. Harold Pate ALSO PRESENT: Administrator Charles T. Stewart County Attorney Gary Moore Openinq Ceremonv. Chairman Tillman opened the meeting by cal I ing on Commissioner Boyne for the invocation, foI iowed by pledge of allegiance to the fIag. Award from Georgia Recreation and Parks Association. Recreation Director Cynthia Williams presented an award received by the Glynn County Recreation Department from the Georgia Recreation and Parks Association, which she planned to have framed so it could be put on display in the Court House. Resolution Proclaiminq "Ducks Unlimited Month. " Chairman Tillman called on Commissioner Boyne to read the f oI I owing resolution designating November as "Ducks Unl imited I'lonth" in Glynn County. Commissioner Boyne then presented a framed copy of this resolution to Gene Strother who was present on behaif of the GIynn County Chapter of Dueks Unlimited. A R.ESOI-['T I ODT R"ECC)GFITZT$TG E)ITCKS T'DTI. I}4I TED }4OAITIjT 9IHEREAS, Ducks Unlimited, Inc. is a unique organization well known throughout the United States and Canada for the promotion of sportsmanshipi and I{HEREAS, Dueks Unlimited is also recognized for its commitment to programs which are designed to promote the growth of nesting areas for wetlands fowl; and I{HEREAS, they have purchased many acres of wetlands in various I ocations throughout the Country for the purpose of preserving the natural habitat of ducks and other fowl; and 9iHEREAS,this outstanding group of citizens have earned the respect and admiration of conservationi.sts who appreciate their efforts to preserve and protect our environment. -

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA Prepared for City of Benicia Department of Public Works & Community Development Prepared by page & turnbull, inc. 1000 Sansome Street, Ste. 200, San Francisco CA 94111 415.362.5154 / www.page-turnbull.com Benicia Historic Context Statement FOREWORD “Benicia is a very pretty place; the situation is well chosen, the land gradually sloping back from the water, with ample space for the spread of the town. The anchorage is excellent, vessels of the largest size being able to tie so near shore as to land goods without lightering. The back country, including the Napa and Sonoma Valleys, is one of the finest agriculture districts in California. Notwithstanding these advantages, Benicia must always remain inferior in commercial advantages, both to San Francisco and Sacramento City.”1 So wrote Bayard Taylor in 1850, less than three years after Benicia’s founding, and another three years before the city would—at least briefly—serve as the capital of California. In the century that followed, Taylor’s assessment was echoed by many authors—that although Benicia had all the ingredients for a great metropolis, it was destined to remain in the shadow of others. Yet these assessments only tell a half truth. While Benicia never became the great commercial center envisioned by its founders, its role in Northern California history is nevertheless one that far outstrips the scale of its geography or the number of its citizens. Benicia gave rise to the first large industrial works in California, hosted the largest train ferries ever constructed, and housed the West Coast’s primary ordnance facility for over 100 years. -

TABBY: the ENDURING BUILDING MATERIAL of COASTAL GEORGIA by TAYLOR P. DAVIS (Under Direction of Dr. Reinberger)

TABBY: THE ENDURING BUILDING MATERIAL OF COASTAL GEORGIA by TAYLOR P. DAVIS (Under direction of Dr. Reinberger) ABSTRACT Tabby is a unique building material found along the coast of the Southeastern United States. This material is all that remains above grade of many past coastal cultures and illustrates much of the history of Coastal Georgia. In this master’s thesis, I present the following areas of research: 1) an explanation of the history and origins of the different generations of tabby, 2) a list of historical tabby sites that I feel are pertinent to its history and cultural significance, and 3) the production of samples of tabby through historical means and the analysis of their compressive strength. With these three concentrations of study, I am able to compile new information on this culturally significant building material. INDEX WORDS: Tabby, Coquina, Limekiln, Limerick, Oglethorpe, Thomas Spalding, Oglethorpe Tabby, Military Tabby, Spalding Tabby, Tabby Revival, Pseudo Tabby, Fort Frederica, St. Augustine, McIntosh County, Glynn County, Camden County TABBY: THE ENDURING BUILDING MATERIAL OF COASTAL GEORGIA by TAYLOR P. DAVIS B.F.A., The University of Georgia, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Historic Preservation Athens, Georgia 2011 © 2011 TAYLOR P. DAVIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABBY: THE ENDURING BUILDING MATERIAL OF COASTAL GEORGIA by TAYLOR P. DAVIS Major Professor: Mark Reinberger Committee: Wayde Brown Larry Millard Scott Messer Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2011 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In this section, I would like to acknowledge the people who have helped me with this project: my mother and father for their patience, support, and advice; my in-laws for them graciously allowing me to use their property for my experimentation and for their advice; my sister for her technical support; Dr. -

Settlement Patterns of the Geechee at Sapelo Island Georgia, from 1860 to 1950

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2021 Our Story, Our Homeland, Our Legacy: Settlement Patterns of The Geechee at Sapelo Island Georgia, From 1860 To 1950 Colette D. Witcher University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Witcher, Colette D., "Our Story, Our Homeland, Our Legacy: Settlement Patterns of The Geechee at Sapelo Island Georgia, From 1860 To 1950" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8889 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Our Story, Our Homeland, Our Legacy: Settlement Patterns of the Geechee at Sapelo Island Georgia, From 1860 To 1950 by Colette D. Witcher A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a concentration in Archaeology Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Thomas J. Pluckhahn, Ph.D. Antoinette T. Jackson, Ph.D. Diane Wallman. Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 10, 2021 Keywords: Historical Archaeology, African-American Archaeology, Post-Emancipation Archaeology, Anarchist Archaeological Theory Copyright © 2021, Colette D. Witcher ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee members Dr. Thomas J. Pluckhahn, Dr. Antoinette T. Jackson, and Dr. Diane Wallman. I thank Dr. -

Street & Number East Side of the Island Ownership of Property

RECEIVED 2280 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service II "'I :»"• 5^^%,IQQfi NATIONAL REGISTER OF '. ISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in "Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms" (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. l. Name of Property historic name HOG HAMMOCK HISTORIC DISTRICT other names/site number N/A _ street & number East side of the island city/ town Sapelo Island (N/A) vicinity of county Mclntosh code GA 191 state Georgia code GA zip code 31327 (N/A) not for publication 3. Classification Ownership of Property: (X) private ( ) public-local (X) public-state ( ) public-federal Category of Property ( ) building(s) (X) district ( ) site ( ) structure ( ) object Number of Resources within Property! Contributing Noncontributinq buildings 59 47 sites 5 0 structures 16 0 objects 0 0 total 80 47 Contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: N/A Name of related multiple property listing: N/A 4. State/Federal Agency certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Jekyll Island National Historic District

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Jekyll Island Historic District AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS NUMBER Between Riverview Dr. § Old Villiage Blvd^Nor FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Jekyll Island — VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Georgia 13 Glynn 127 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE V _LDISTRICT <LpUBLIC _ OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE ^MUSEUM __BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL ^_PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS -1±YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: QOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Jekyll Island State Park Authority STREET & NUMBER 214 Trinity-Washington Building CITY, TOWN STATE Atlanta _ VICINITY OF Georgia ULOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Jekvl 1 T<?1flT1rl ^i-fft-t* Pa-rV An* >>r»-K»-i -t-\r v^cis.j' j. j. <L«3 J. culU. OCclLC JrclXJx rVULflOilLy STREETS. NUMBER 214 Trinity-Washington Building CITY, TOWN " STATE Atlanta Georgia Q REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE —FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD —RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR —UNEXPOSED ———————————DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The village is comprised of 240 acres on the western shores of Jekyll Island in a beautiful setting of live oaks. -

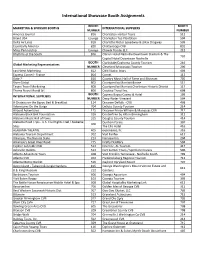

IS17 Booth Sign List

International Showcase Booth Assignments BOOTH BOOTH MARKETING & SPONSOR BOOTHS INTERNATIONAL SUPPLIERS NUMBER NUMBER America Journal 816 Charleston Harbor Tours 512 Brand USA Lounge Charleston Tea Plantation 504 Delta Air Lines 818 Charlotte Motor Speedway & zMax Dragway 509 Essentially America 820 Chattanooga CVB 832 Miles Partnership Lounge Chawla Pointe, LLC 212 Rhythms of the South 826 Clarion Hotel Nashville Downtown Stadium & The 707 Capitol Hotel Downtown Nashville BOOTH Clarksdale/Coahoma County Tourism 216 Global Marketing Representatives NUMBER Cleveland Mississippi Tourism 206 East West Marketing 812 CNN Studio Tours 404 Express Conseil ‐ France 804 Cornet 112 Gate 7 810 Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum 705 River Global 802 Courtyard by Marriott Boone 515 Target Travel Marketing 808 Courtyard by Marriott Charleston Historic District 117 Thema Nuovi Mondi Srl 806 Creative Travel Inc. 608 BOOTH Cypress Bayou Casino & Hotel 109 INTERNATIONAL SUPPLIERS NUMBER Deep Water Vineyard 504 A Chateau on the Bayou Bed & Breakfast 114 Discover DeKalb ‐ CVB 408 Adventures On the Gorge 704 DeSoto County Tourism 214 Airboat Adventures 115 Discover Prince William & Manassas CVB 712 Alabama Black Belt Foundation 316 DoubleTree by Hilton Birmingham 312 Alabama Music Hall of Fame 315 Douglas County Tourism 414 Alabama Road Trips ‐ U.S. Civil Rights Trail / Alabama Dunham Farms 307 306 Sites The Ellis Hotel 416 ALABAMA THEATRE 405 experience, llc 316 Alabama Tourism Department 302 Visit Fairfax 613 Arkansas, The Natural State 213 Fairview Inn 204 Arkansas's Great River Road 215 Firefly Distillery 504 Explore Asheville CVB 513 Florence, AL Tourism 317 Asheville Outlets 513 Fort Sumter Tours / SpiritLine Cruises 506 Atlanta Adventure Tours 408 Visit Franklin Tennessee ‐ Nashville South 709 Atlanta CVB 402 Fredericksburg Regional Tourism 712 Atlanta Metro Market 516 Gaylord Opryland Resort 707 Avery Island ‐ Tabasco & Jungle Gardens 105 George Washington's Mount Vernon Estate and 613 B.B. -

2012 BOURBON FIELD: PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS of a BARRIER ISLAND PLANTATION SITE, SAPELO ISLAND, GEORGIA by Rachel Laura Devan

BOURBON FIELD: PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS OF A BARRIER ISLAND PLANTATION SITE, SAPELO ISLAND, GEORGIA by Rachel Laura DeVan Perrine B.A., The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts 2012 The thesis of Rachel Laura DeVan Perrine is approved: ____________________________________________ _______________________ Norma J. Harris, M.A., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _______________________ George B. Ellenberg, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _______________________ David C. Crass, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _______________________ John E. Worth, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _______________________ John R. Bratten, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _______________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my late grandma, Dorothy Ore, who was supportive and enthusiastic about my decision to pursue a career in archaeology and whose zest for life and positive attitude will always be an inspiration to me. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Over the course of my thesis work, I have been very fortunate in having help through every stage of the project. I could not have completed my thesis without the assistance and support of those individuals who lent a hand along the way and I would like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude. First of all, I would like to thank my UWF thesis committee members, Norma Harris, John Worth, and George Ellenberg for their guidance and help during the various phases of my research. -

Freiberg Online Geoscience FOG Is an Electronic Journal Registered Under ISSN 1434-7512

FOG Freiberg Online Geoscience FOG is an electronic journal registered under ISSN 1434-7512 2021, VOL 58 Broder Merkel & Mandy Hoyer (Eds.) FOG special volume: Proceedings of the 6th European Conference on Scientific Diving 2021 178 pages, 25 contributions Preface We are happy to present the proceedings from the 6th European Conference on Scientific Diving (ECSD), which took place in April 2021 as virtual meeting. The first ECSD took place in Stuttgart, Germany, in 2015. The following conferences were hosted in Kristineberg, Sweden (2016), Funchal, Madeira/Portugal (2017), Orkney, Scotland/UK (2018), and Sopot, Poland (2019), respectively. The 6th ECSD was scheduled for April 2020 but has been postponed due to the Corona pandemic by one year. In total 80 people registered and about 60 participants were online on average during the two days of the meeting (April 21 and 22, 2021). 36 talks and 15 posters were presen-ted and discussed. Some authors and co-authors took advantage of the opportunity to hand in a total of 25 extended abstracts for the proceedings published in the open access journal FOG (Freiberg Online Geoscience). The contributions are categorized into: - Device development - Scientific case studies - Aspects of training scientists to work under water The order of the contributions within these three categories is more or less arbitrary. Please enjoy browsing through the proceedings and do not hesitate to follow up ideas and questions that have been raised and triggered during the meeting. Hopefully, we will meet again in person -

A Visitor's Guide to Accessing Georgia's Coastal Resources

A Visitor’s Guide to Accessing Georgia’s Coastal Resources Beaches & Barrier Islands Cultural & Historic Sites Rivers & Waterways Wildlife Viewing & Walking Trails FREE COPY - NOT FOR SALE A Visitor’s Guide to Accessing Georgia’s Coastal Resources acknowledgements This Guide was prepared by The University of Georgia Marine Extension Service under grant award # NA06NOS4190253 from the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of OCRM or NOAA. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Georgia Department of Natural Resources’ Wildlife Resources Division and Parks and Historic Sites Division for their assistance and for permission to use certain descriptions, maps, and photographs in the drafting of this Guide. The authors also acknowledge the Coastal Resources Division and particularly Beach Water Quality Manager Elizabeth Cheney for providing GIS maps and other helpful assistance related to accessing Georgia beaches. This Access Guide was compiled and written by Phillip Flournoy and Casey Sanders. University of Georgia Marine Extension Service 715 Bay Street Brunswick, GA 31520 April 2008 Photo Credits: ~ Beak to Beak Egret Chicks by James Holland, Altamaha Riverkeeper ~ Sapelo Island Beach by Suzanne Van Parreren, Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research Reserve ~ Main House, Hofwyl Plantation by Robert Overman, University of Georgia Marine Extension Service ~ J. T. Good, A Chip Off the Block by Captain Brooks Good table of contents Acknowledgements. 2 Map of Georgia Coastal Counties and the Barrier Islands. 5 Foreword. 6 1. Beaches and Barrier Islands . 7 a. Chatham County.