ABSTRACT Title of Document: RUINS and WRINKLES: REVALUING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 12. 1978~ Designation List 118 LP-0992 CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1928- 1930; architect William Van Alen. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1297, Lot 23. On March 14, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a_public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Chrysler Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 12). The item was again heard on May 9, 1978 (Item No. 3) and July 11, 1978 (Item No. 1). All hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Thirteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were two speakers in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters and communications supporting designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Chrysler Building, a stunning statement in the Art Deco style by architect William Van Alen, embodies the romantic essence of the New York City skyscraper. Built in 1928-30 for Walter P. Chrysler of the Chrysler Corporation, it was "dedicated to world commerce and industry."! The tallest building in the world when completed in 1930, it stood proudly on the New York skyline as a personal symbol of Walter Chrysler and the strength of his corporation. History of Construction The Chrysler Building had its beginnings in an office building project for William H. Reynolds, a real-estate developer and promoter and former New York State senator. Reynolds had acquired a long-term lease in 1921 on a parcel of property at Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street owned by the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. -

Reynolds Building Overall View Rear View

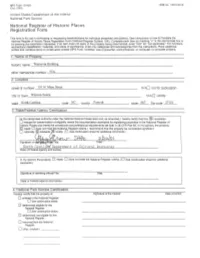

NORTH CAROLINA STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE Office of Archives and History Department of Cultural Resources NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Reynolds Building Winston-Salem, Forsyth County, FY2141, Listed 8/19/2014 Nomination by Jen Hembree Photographs by Jen Hembree, November 2013 and March 2014 Overall view Rear view NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Reynolds Building Other names/site number: R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Office Building Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 51 E. Fourth Street City or town: Winston-Salem State: NC County: Forsyth Not For Publication:N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Annual Report on the Economic Impact of the Federal Historic Tax Credit for FY 2017

Annual Report on the Economic Impact of the Federal Historic Tax Credit for FY 2017 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Technical Preservation Services Front Cover Image: Zeigler’s Drug Store/Allen’s Hall, Florence, South Carolina Photo: Lucas Brown, Kickstand Studio Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Civic Square Building, 33 Livingston Avenue New Brunswick, NJ 08901 848-932-5475 http://bloustein.rutgers.edu/ [email protected] The executive summary is based on the findings of a National Park Service-funded study undertaken through a cooperative agreement with Rutgers University’s Center for Urban Policy Research. Rutgers University is responsible for the content of the study. Some additional demographic analysis was provided courtesy of PolicyMap. The National Trust for Historic Technical Preservation Services Preservation assisted the National Park Service National Park Service U. S. Department of the Interior in the preparation of the case studies. Washington, DC 20240 https://www.nps.gov/tps/ September 2018 A Message from the National Park Service Beyond the National Park System, the National Park Service (NPS) is part of a national preservation partnership working to promote the preservation of historic resources in communities small and large throughout the country. For the past 40 years, the NPS, in partnership with the State Historic Preservation Offices, has administered the Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives Program. The program provides a 20% Federal tax credit to property owners who undertake a substantial rehabilitation of a historic building in a business or income-producing use while maintaining its historic character. -

Forest's Drive Toward NC~!\.A Finals Is

... ' ,. '. \ :: ' ' . Friday ·Night: Saturday Night: W~ak~ Forest 78 Wake Forest 86 St. Bonaventure 73 nlll aub i lark St. Joseph's 96 -, / * NUMBER 21 No1·th 20; 1961 * Wake Forest College, Winston-Salem, Carolina, J.\'londay,.March VOLUME ~VI I --------------~------• Wake· Forest's Drive Toward NC~!\.A Finals i;;i,~: ~ ' . - - . ' - Is ·~~Halted By St. Joseph's Five In Charlotte A gari~nt second half comeback ,to put the Deacs within six points stealing tactic~. the game, all in the operrl,ng min- 08; However, after the 11-minute Chappell and Hart and another two that this was the turning pomt. by the·deiteJimined Deacons brought of the Hawks. At the same time, St. Joseph was utes and it was Lenny Chappell, mark the axe Jell on 'the Deacons. points from the foul line by Hart St. Joseph's scoring was well dis them vnthill:six pOints of the NCAA BUll: the Hawks. immediate)iy cap- able to maintain constant pressure who scored a total of 32 points in Taking advantage of Wake's cut the Hawk's lead to 14. tributed with six players hitting. semi-finaliii=in Kansas City, but a italized .on the Deacons' disorgan• on the Deacs and tore up· the ..net Ithe game, who did it in each case. errors -the Hawks outscored the The. Hawks, however, tightened double figures. couple of.costly defensive mis~ues ized defense a.!ld scored two _con-I with its shooting. St. Joe's was the first to score, Deacons; 28 to 10, in rtb.e remaining up and t:he •Deacs were able only Chappell's 32 points was high for prevented. -

Sifica Wner Of

8 4 018 ,P " (7-11) See Instructions in, How to ;r.UTln,/Pf'fP National Register Forms all aooIlCalf:)l~ sections historic Nissen Buildin~ and/or common First Union Buildin o street & number 310 West Fourth Street __ not for pulbllc:atllon city, town Winston-Salem __ vicintty of us: gut I II iii' . state North Carolina code 037 Forsyth code 067 sifica Category Ownership Status Present Use __ district __ public --X.- occupied ,. __ agri~ulture __ museum -X- bulldlng(s) -X- private __ unoccupied -X- commercial __ park __ structure _both __ work in progress _ educational __ private residence __ site Public Acquisa"tion Accessible __ entertainment __ religious __ object __ in process __ yes: restricted __ government __ scientific __ being considered --X- yes: unrestricted _ industrial __ transportation ~/A _no __ other: wner of name - Booke & Company and BRIC, Inc. (A wholly-owned subsidiary of Booke & Co.) street & number 710 Coliseum Drive state North Carolina courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Forsyth County Hall of Justice, Register of Deeds street & number Main Street state North Carolina IP'U'iI"f'I.1III,riv been determined --X- no dll'e 1981 hltderlll stlte IDCIII N. C. Division of town stete North Carolina ~ __ ruins __ fair 1 • The Nissen Building stands on the corner of Fourth and Cherry Streets in the heart of Winston-Salem's retail and office district. It has been a prominent feature on Winstop-Salem's skyline since its construction in 1926 by William M. Nissen on the site of the former Y.M.C.A. -

RJR ·Nabisco Donates Building ·To WFU Corporate Gift May .Be

OLD AND LACK Volume ·70 No. 15 Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem North Carolina Friday, January 16, 1987 RJR ·Nabisco Donates Building ·to WFU Corporate Gift May .Be . Largest to Education By CRISI'lNE M. VARHOLY also an extraordinary vote of con Old Gold and Black P.eporter fidence in Wake Forest." · Hearn said that the gift was a sur RJR Nabisco Inc. announced prise but that "there had been yesterday that it will donate its cor discussions between the universi porate · headquarters building on ty and the company about our space Reynolds Boulevard to Wake Forest problems on campus." Hearn could University. The company will move not confirm whether or not th!l gift its corporate headquarters to Atlan had been made in 1986 before the ta during 1987. change in tax laws. Completed in 1W7 at a cost of Ownership of the building will $40 million, the 519,000 square-foot transfer to Wake Forest in March. building and its surrounding land RJR Nabisco will continue to use may be the largest corporate gift the building under an agreement ever donated to an educational with the university until the move institution. to Atlanta in September, according · Russell H. Brantley Jr., the direc to the company's prepared tor of communications, said that the statement. largest previous corporate gift was An administrative group headed a $62 million film library donated by John P. Anderson, the vice by the Hearst Corporation to the president for administration and Sam University of California. The se planning, and Leon H. Corbett Jr., RJR Nabisco contributed their 518,000 square foot headquarters building without any stipulations or restrictions concerning its use. -

Tobacco Excise Taxes CI Products, the Agency Does Have Broad Authority Over Virtually Every Aspect of U.S

Our Commercial Integrity pillar covers a broad range of business, social and CI environmental issues – from maintaining a responsible supply chain to reducing our Commercial environmental footprint. TT Environmental Sustainability YTP Integrity Our Commitment THR We recognize our companies’ manufacturing operations rely on resources and produce For the past waste streams that may impact the environment. We also understand that properly six years, RAI’s CI managing these impacts is the right thing to do for the environment and for our bottom line. Our operating companies are committed to continually driving their environmental, operating companies health and safety (EHS) programs in accordance with the guiding principles set out in have held an annual CI RAI’s Environmental, Health and Safety Policy. EHS Symposium, While our operating companies share common metrics and principles, each company’s bringing together all efforts are led by a senior EHS manager who is responsible for managing that company’s EHS representatives, environmental, health and safety programs, and establishing improvement priorities, as well as other performance goals and metrics. stakeholders from EHS managers meet regularly as a group to work toward common RAI goals, fostering within and outside innovation through sharing of best practices and providing tools to the operating the companies. companies. A good example is the EHS Roadmap, a self-assessment tool for RAI’s operating companies and their manufacturing sites, that guides continuous improvements in environmental, health and safety programs. By regularly facilitating conversations across operating companies, we share learnings and can readily adopt improvements. For the past six years, RAI’s operating companies have held an annual EHS Symposium, bringing together all EHS representatives, as well as other stakeholders from within and outside the companies. -

2008 Forsyth County Phase II

Cover photos (clockwise from top left): R. Clyde and Lena Pratt House, African American Cemetery in Kernersville, Memorial Industrial School, Camp Civitan, former Burkhead United Methodist Church/Ambassador Cathedral, Felix and Clarice Huffman Farm TABLE OF CONTENTS I. A Brief History of Forsyth County 3 II. Changes in Forsyth County since the 1978-80 Architectural Survey 11 III. Forsyth County Architectural Survey History 13 IV. 2006-2007 Phase I Reconnaissance Survey Update Methodology 15 V. 2006-2007 Phase I Reconnaissance Survey Update Results 19 VI. 2006-2007 Phase I Reconnaissance Survey Update Data Gaps 21 VII. 2007-2008 Phase II Reconnaissance and Partial Intensive Survey 23 Update Methodology VIII. 2007-2008 Phase II Reconnaissance and Partial Intensive Survey 25 Update Results IX. Planning for the Completion of the Survey Update 28 X. Bibliography 30 Appendix A. Phase II Study List Recommendations A-2 Appendix B. Winston-Salem Subdivisions 1930-1970 B-2 Appendix C. Modernist Properties C-2 Appendix D. Professional Qualifications D-2 Forsyth County Phase II Survey Update Report 2 Fearnbach History Services, Inc. / August 2008 I. A Brief History of Forsyth County Rural Beginnings The earliest inhabitants of the area that is now Forsyth County were Native Americans who settled along a river they called the “Yattken,” a Siouan word meaning “place of big trees.” Archaeological investigation of a rock shelter near the river’s “Great Bend” revealed that the cave had been used for 8,500 years, initially by nomadic hunters and then by villagers who farmed the fertile flood plain. Although these Native Americans did not espouse tribal affiliations, early white explorers categorized them as Saponi and Tutelo. -

Duke and Reynolds: Urban and Regional Development Through Business, Politics, and Philanthropy

DUKE AND REYNOLDS: URBAN AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT THROUGH BUSINESS, POLITICS, AND PHILANTHROPY by Brianna Michelle Dancy A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2016 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Aaron Shapiro ______________________________ Dr. Mark Wilson ______________________________ Dr. Shepherd McKinley ii ©2016 Brianna Michelle Dancy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT BRIANNA MICHELLE DANCY. Duke and Reynolds: urban and regional development through business, politics, and philanthropy. (Under the direction of DR. AARON SHAPIRO) The Industrial Revolution witnessed an increase in wealthy entrepreneurs who were also philanthropists. During this era, James Buchanan (Buck) Duke and Richard Joshua (R.J.) Reynolds led the tobacco production industry in North Carolina. These industrialists and their families became active agents in defining southern Progressivism and modern philanthropy during the twentieth century. Southern philanthropy differed from the North. Northern philanthropists donated their wealth at home and abroad, while southern philanthropists contributed to the social welfare of their communities and regions. In addition, politics in the South created a unique opportunity for these industrialists to become paternalistic leaders in their respective communities. Legal segregation in the South also limited the impact of the industrialists’ philanthropy. However, unlike some of their fellow southern industrialists, the Duke and Reynolds families contributed to African American causes. This study demonstrates the key role that the Duke and Reynolds families played in the development of their respective cities and the Piedmont region, as well as their role in improving social welfare. Examining these cities and the region through the intersection of business, politics, and philanthropy explains the relationship between company growth and urban development. -

Forsyth County Phase III Survey Report

Forsyth County Phase III Survey Report Prepared for: Forsyth County Historic Resources Commission City-County Planning Board P. O. Box 2511 Winston-Salem, NC 27102 Prepared by: Heather Fearnbach • Fearnbach History Services, Inc. • 3334 Nottingham Road • Winston-Salem, NC 27104 August 2009 Cover photos (clockwise from top left): (former) Western Electric Plant on Old Lexington Road, Snyder Hall on the Forsyth Technical Community College Main Campus, (former) McLean Trucking Headquarters, First Baptist Church at 700 N. Highland Avenue, Sunrise Towers, Dr. Fred K. and Edna W. Garvey House TABLE OF CONTENTS I. A Brief History of Forsyth County through the 1920s 3 II. Changes in Forsyth County since the 1978-80 Architectural Survey 9 III. Forsyth County Architectural Survey History 11 IV. 2006-2007 Phase I Reconnaissance Survey Update Methodology 14 V. 2006-2007 Phase I Reconnaissance Survey Update Results 17 VI. 2006-2007 Phase I Reconnaissance Survey Update Data Gaps 19 VII. 2007-2008 Phase II Survey Update Methodology 21 VIII. 2007-2008 Phase II Survey Update Results 23 IX. 2008-2009 Phase III Survey Methodology and Results 26 X. Historical and Architectural Contexts and Property Types 29 Community Development Context, 1930-1969 30 Modern Architecture Context 38 Winston-Salem Architects, 1930-1969 43 Winston-Salem Building Contractors: 1930-1969 51 Property Type 1: Residential 54 Property Type 2: Subdivisions 69 Property Type 3: Religious 85 Property Type 4: Industrial 93 Property Type 5: Commercial 94 Property Type 6: Governmental 101 Property Type 7: Educational 103 XI. 2009-2010 Phase IV Scope of Work 110 XII. Bibliography 111 Appendix A. -

Source: "Should Be Confined to VAT" (To a 1 5% VAT)

Report from the „Seminar on the taxation of tobacco in the European Union", 28-29 September 2006 (Budapest, Grand Hotel Royal): by Tibor Szilagyi [currently working at WHO Secretariat] The conference has been organised by the International Tax and Investment Center (ITIC), an international N'GO registered in the US. The website of this organisation (www. iticnei.org) previously acknowledged receiving support from tobacco companies. Audience: Around 50 people, representing primarily finance ministries and financial research institutes from Central and Eastern Ruropean countries. The only speaker from the Ruropean Commission has been Mr Alexander Wiedovv, director of indirect taxation and tax administration of the EC. The Chairman of the conference has been Prof Sijbren Cnossen of the University of Maastricht. Another key speaker Mr Adrian Cooper (UK), managing director of Oxford Economic Forecasting. Both have been actively put forward tobacco industry arguments with regard to taxation of tobacco products. The latter has published a ..special report" with this occasion, entitled ..Addressing the RU cigarette excise regime review 2006". The report ~ the introduction says ••- analyses the strengths and weaknesses of the RU taxation regime and ..considers how it should be reformed". The report considers the escalation of the black market as a sign of a ..destabilized cigarette market", which is primarily caused by tax and price increases. The report publishes a table (page 10) on the share of black market in selected RU countries, mentioning as source ..industry estimates". It considers, for example, 25% of the Hungarian or 35% of Lithuanian market as ..black", without even mentioning on which basis these estimates have been made. -

Hi Ric PI Es

NPS Form 10-900 OMS No. 10024-001 S (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Hi ric PI es This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural dassification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. historic name Wachovia Building other names/site number _N_I_A______________________________ _ street & number 301 N. Main Street NIAO not for publication city or town _W_ill_'_st_o_n_-S_a_l_e_ffi _________________________ _ NIAD vicinity state North Carolina code ~ county _F_o_rs..:..yt_h______ _ code 067 Zip code 27101 As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this t8l nomination o request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property OCJ meets 0 does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant o nationally (8l statewide !8llocally. (0 See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of Date' North Carolin DeDartrnent of Cultural Resources State of Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property 0 meets 0 does not meet the National Register criteria.