Freedom on the Net 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predators 2021 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PREDATORS 2021 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Azerbaijan 167/180* Eritrea 180/180* Isaias AFWERKI Ilham Aliyev Born 2 February 1946 Born 24 December 1961 > President of the Republic of Eritrea > President of the Republic of Azerbaijan since 19 May 1993 since 2003 > Predator since 18 September 2001, the day he suddenly eliminated > Predator since taking office, but especially since 2014 his political rivals, closed all privately-owned media and jailed outspoken PREDATORY METHOD: Subservient judicial system journalists Azerbaijan’s subservient judicial system convicts journalists on absurd, spurious PREDATORY METHOD: Paranoid totalitarianism charges that are sometimes very serious, while the security services never The least attempt to question or challenge the regime is regarded as a threat to rush to investigate physical attacks on journalists and sometimes protect their “national security.” There are no more privately-owned media, only state media assailants, even when they have committed appalling crimes. Under President with Stalinist editorial policies. Journalists are regarded as enemies. Some have Aliyev, news sites can be legally blocked if they pose a “danger to the state died in prison, others have been imprisoned for the past 20 years in the most or society.” Censorship was stepped up during the war with neighbouring appalling conditions, without access to their family or a lawyer. According to Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh and the government routinely refuses to give the information RSF has been getting for the past two decades, journalists accreditation to foreign journalists. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Freedom to Write Index 2019

FREEDOM TO WRITE INDEX 2019 Freedom to Write Index 2019 1 INTRODUCTION mid global retrenchment on human rights In 2019, countries in the Asia-Pacific region impris- Aand fundamental freedoms—deepening oned or detained 100 writers, or 42 percent of the authoritarianism in Russia, China, and much of the total number captured in the Index, while countries Middle East; democratic retreat in parts of Eastern in the Middle East and North Africa imprisoned or Europe, Latin America, and Asia; and new threats detained 73 writers, or 31 percent. Together these in established democracies in North America and two regions accounted for almost three-quarters Western Europe—the brave individuals who speak (73 percent) of the cases in the 2019 Index. Europe out, challenge tyranny, and make the intellectual and Central Asia was the third highest region, with case for freedom are on the front line of the battle 41 imprisoned/detained writers, or 17 percent of to keep societies open, defend the truth, and resist the 2019 Index; Turkey alone accounted for 30 of repression. Writers and intellectuals are often those cases. By contrast, incarceration of writers is among the canaries in the coal mine who, alongside relatively less prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, with journalists and human rights activists, are first 20 writers, or roughly eight percent of the count, and targeted when a country takes a more authoritarian the Americas, with four writers, just under two percent turn. The unjust detention and imprisonment of the count. The vast majority of imprisoned writers, of writers and intellectuals impacts both the intellectuals, and public commentators are men, but individuals themselves and the broader public, who women comprised 16 percent of all cases counted in are deprived of innovative and influential voices the 2019 Index. -

Human Rights Abuses in Azerbaijan

1 1 Human Rights House Network The Human Rights House Network (HRHN) is a community of human rights defenders working for more than 100 independent organisations operating in 16 Human Rights Houses in 13 countries. Empowering, supporting, and protecting human rights defenders, the Network members unite their voices to promote the universal freedoms of assembly, organisation, and expression, and the right to be a human rights defender. The Secretariat, the Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) based in Oslo, with offices in Geneva and Brussels, stewards the community, raising awareness internationally, raising concerns at the Council of Europe, the European Union and the United Nations, and other international institutions, and coordinating best use and sharing of the knowledge, expertise, influence, and resources within HRHN. Contact persons for the report: Alexander Sjödin European Advocacy Officer, Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) Email: [email protected] Tel: +32 49 78 15 918 Florian Irminger Head of Advocacy, Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) Email: [email protected] Tel: +41 79 751 80 42 Oslo office Menneskerettighetshuset Kirkegata 5, 0153 Oslo (Norway) Geneva office Rue de Varembé 1 (5th floor) PO Box 35, 1211 Geneva 20 (Switzerland) Brussels office Rue de Trèves 45, 1040 Brussels (Belgium) 2 For human rights defenders in Azerbaijan In June 2014, a number of Azerbaijani human rights defenders, including Emin Huseynov, Rasul Jafarov, and Intigam Aliyev organised a side-event in Strasbourg when President Aliyev addressed the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). Two months later, Rasul Jafarov and Intigam Aliyev were arrested, and shortly thereafter Emin Huseynov fled to the Swiss Embassy in Baku for protection against his own impending arrest. -

World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: 2017/2018 Global Report

Published in 2018 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 7523 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO and University of Oxford, 2018 ISBN 978-92-3-100242-7 Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repos- itory (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The present license applies exclusively to the textual content of the publication. For the use of any material not clearly identi- fied as belonging to UNESCO, prior permission shall be requested from: [email protected] or UNESCO Publishing, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP France. Title: World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: 2017/2018 Global Report This complete World Trends Report Report (and executive summary in six languages) can be found at en.unesco.org/world- media-trends-2017 The complete study should be cited as follows: UNESCO. 2018. World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: 2017/2018 Global Report, Paris The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authori- ties, or concerning the delimiation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

A CELEBRATION of PRESS FREEDOM World Press Freedom Day UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY

Ghanaian students at World Press Freedom Day 2018 Accra, Ghana. Photo credit: © Ghana Ministry of Information A CELEBRATION OF PRESS FREEDOM World Press Freedom Day UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY An overview Speakers at World Press Freedom Day 2017 in Jakarta, Indonesia Photo credit: ©Voice of Millenials very year, 3 May is a date which celebrates Ababa on 2-3 May with UNESCO and the African Union the fundamental principles of press freedom. Commission. The global theme for the 2019 celebration It serves as an occasion to evaluate press is Media for Democracy: Journalism and Elections in freedom around the world, defend the media Times of Disinformation. This conference will focus from attacks on their independence and on the contemporary challenges faced by media Epay tribute to journalists who have lost their lives in the in elections, including false information, anti-media exercise of their profession. rhetoric and attempts to discredit truthful news reports. World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) is a flagship The debates will also highlight the distinctiveness of awareness-raising event on freedom of expression, and journalism in helping to ensure the integrity of elections, in particular press freedom and the safety of journalists. as well as media’s potential in supporting peace and Since 1993, UNESCO leads the global celebration with reconciliation. a main event in a different country every year, organized In the last two editions, World Press Freedom together with the host government and various partners Day has focused on some of the most pressing issues working in the field of freedom of expression. -

Azerbaijan | Freedom House

Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan About Us DONATE Blog Mobile App Contact Us Mexico Website (in Spanish) REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Subscribe Donate NATIONS IN TRANSIT - View another year - ShareShareShareShareShareMore 7 Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Nations in Transit 2014 DRAFT REPORT 2014 SCORES PDF version Capital: Baku 6.68 Population: 9.3 million REGIME CLASSIFICATION GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,410 Consolidated Source: The data above are drawn from The World Bank, Authoritarian World Development Indicators 2014. Regime 6.75 7.00 6.50 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 1 of 23 6/25/2014 11:26 AM Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan Azerbaijan is ruled by an authoritarian regime characterized by intolerance for dissent and disregard for civil liberties and political rights. When President Heydar Aliyev came to power in 1993, he secured a ceasefire in Azerbaijan’s war with Armenia and established relative domestic stability, but he also instituted a Soviet-style, vertical power system, based on patronage and the suppression of political dissent. Ilham Aliyev succeeded his father in 2003, continuing and intensifying the most repressive aspects of his father’s rule. -

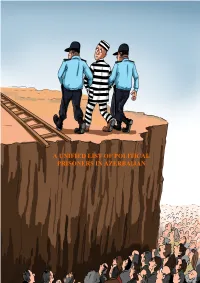

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

AZERBAIJAN: Investigative Journalist Khadija Ismayilova Sentenced to 7.5 Years in Jail

PRESS RELEASE - THE OBSERVATORY AZERBAIJAN: Investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova sentenced to 7.5 years in jail Geneva-Paris, September 1, 2015 – The sentencing of prominent investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova to 7.5 years in prison was handed down today before the Baku Court of Grave Crimes. Arbitrarily detained since December 5, 2014, her conviction is based on trumped-up charges and aims at preventing her from carrying out her legitimate activities, the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders said today. On September 1, 2015, the Baku Court of Grave Crimes sentenced Ms. Khadija Ismayilova to 7,5 years imprisonment on charges of embezzlement, illegal entrepreneurship, tax evasion, and abuse of office. On August 21, the Prosecution had demanded for her 9 years of jail. Internationally recognised independent reporter1 and journalist of the Azerbaijani radio Azadliq (“Radio Freedom”), Ms. Ismayilova was arrested on December 5, 2014 on charges of "inciting" her ex-partner "to commit suicide". Although in April 2015 the alleged victim retreated his accusations, claiming his testimony was given under pressure, blackmail and torture, the prosecution did not take it into account and maintained the charges. In February 2015, Ms. Ismayilova was further accused of embezzlement, illegal entrepreneurship, tax evasion and abuse of office. During the hearings, no evidence of these accusations was presented. The crackdown on civil society, going on in Azerbaijan since last year, has recently seen other prominent human rights defenders sentenced on similar trumped up charges: Mr. Rasul Jafarov and Mr. Intigam Aliyev sentenced in appeal respectively to 6.3 and 7.5 years of jail, and Ms. -

Azerbaijan: Downward Spiral: Continuing Crackdown on Freedoms in Azerbaijan

DOWNWARD SPIRAL: CONTINUING CRACKDOWN ON FREEDOMS IN AZERBAIJAN Amnesty International Publications First published in 2013 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2013 Index: EUR 55/010/2013 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. CONTENTS 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 2. Shrinking space for free media ................................................................................... 7 2.1 The continuing use of defamation suits to silence government critics ........................ 7 2.2 State control of broadcast media ........................................................................... 8 2.3 Harassment, intimidation and imprisonment of journalists ...................................... -

Interim Report on the Nomination and Registration of Candidates

ELECTION MONITORING AND DEMOCRACY STUDIES CENTER in cooperation with VOLUNTEERS INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS 9 October 2013 INTERIM REPORT ON THE NOMINATION AND REGISTRATION OF CANDIDATES 16 SEPTEMBER BAKU I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center (EMDS) and Volunteers International Cooperation Public Union (VIC) conducted long-term observation of the first stage of the 9 October 2013 Presidential Elections (10 August-14 September) of the Republic of Azerbaijan. The monitoring of this stage, which included the pre-election environment and process of nomination and registration of candidates, was carried out in 89 election constituencies and nationwide. Information reflected in this report is collected from 32 long-term observers, presidential candidates and their campaign headquarters, members of election commissions and voters and verified by both organizations. Despite some technical improvements in the process of preparation to the elections, observers noted abuse of administrative resources and lack of improvement with regard to pre-election environment. EMDS and VIC note with concern that legal framework stipulated by the current Election Code and situation of political freedoms prior to the elections, particularly freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association, create more restricted pre-election environment in comparison with previous elections. The process of nomination and registration of candidates started on 10 August and completed on 9 September. According to the CEC’s information for 13 September, 21 persons received signature collection forms and 14 of them submitted forms. 10 candidates submitting signature collection forms were registered as presidential candidate by the CEC, while 4 persons were refused registration. During the process of signature collection in favor of presidential candidates, violations occurred in previous elections were recorded again.