The Significance of Creating First Nation Traditional Names Maps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wollaston Road

WOLLASTON LAKE ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Biophysical Environment 4.0 Biophysical Environment 4.1 INTRODUCTION This section provides a description of the biophysical characteristics of the study region. Topics include climate, geology, terrestrial ecology, groundwater, surface water and aquatic ecology. These topics are discussed at a regional scale, with some topics being more focused on the road corridor area (i.e., the two route options). Information included in this section was obtained in full or part from direct field observations as well as from reports, files, publications, and/or personal communications from the following sources: Saskatchewan Research Council Canadian Wildlife Service Beverly and Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board Reports Saskatchewan Museum of Natural History W.P. Fraser Herbarium Saskatchewan Environment Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre Environment Canada Private Sector (Consultants) Miscellaneous publications 4.2 PHYSIOGRAPHY Both proposed routes straddle two different ecozones. The southern portion is located in the Wollaston Lake Plain landscape area within the Churchill River Upland ecoregion of the Boreal Shield ecozone. The northern portion is located in the Nueltin Lake Plain landscape area within the Selwyn Lake Upland ecoregion of the Taiga Shield ecozone (Figure 4.1). (SKCDC, 2002a; Acton et al., 1998; Canadian Biodiversity, 2004; MDH, 2004). Wollaston Lake lies on the Precambrian Shield in northern Saskatchewan and drains through two outlets. The primary Wollaston Lake discharge is within the Hudson Bay Drainage Basin, which drains through the Cochrane River, Reindeer Lake and into the Churchill River system which ultimately drains into Hudson Bay. The other drainage discharge is via the Fond du Lac River to Lake Athabasca, and thence to the Arctic Ocean. -

Chapter 4 – Project Setting

Chapter 4 – Project Setting MINAGO PROJECT i Environmental Impact Statement TABLE OF CONTENTS 4. PROJECT SETTING 4-1 4.1 Project Location 4-1 4.2 Physical Environment 4-2 4.3 Ecological Characterization 4-3 4.4 Social and Cultural Environment 4-5 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map ......................................................................................................... 4-1 Figure 4.4-1 Communities of Interest Surveyed ....................................................................................... 4-6 MINAGO PROJECT ii Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4. PROJECT SETTING 4.1 Project Location The Minago Nickel Property (Property) is located 485 km north-northwest of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada and 225 km south of Thompson, Manitoba on NTS map sheet 63J/3. The property is approximately 100 km north of Grand Rapids off Provincial Highway 6 in Manitoba. Provincial Highway 6 is a paved two-lane highway that serves as a major transportation route to northern Manitoba. The site location is shown in Figure 4.1-1. Source: Wardrop, 2006 Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map MINAGO PROJECT 4-1 Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4.2 Physical Environment The Minago Project is located within the Nelson River sub-basin, which drains northeast into the southern end of the Hudson Bay. The Minago River and Hargrave River catchments, surrounding the Minago Project Site to the north, occur within the Nelson River sub-basin. The William River and Oakley Creek catchments at or surrounding the Minago Project Site to the south, occur within the Lake Winnipeg sub-basin, which flows northward into the Nelson River sub-basin. The topography in these watersheds varies between elevation 210 and 300 m.a.s.l. -

Review of Regional Cumulative Effects Assessment

Review of Regional Cumulative Effects Assessment October 2017 Prepared for: Manitoba Clean Environment Commission Prepared by: Halket Environmental Consultants Inc. For: O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation OPCN Review of the RCEA ii Executive Summary Halket Environmental Consultants was engaged by O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation to review the Regional Cumulative Effects Assessment for Hydroelectric Developments on the Churchill, Burntwood and Nelson River Systems, conducted by Manitoba and Manitoba Hydro. After reviewing the assessment we were surprised by the lack of suitable scoping and analyses and also the lack of assessment concerning mitigation measures. Therefore, we, O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation (OPCN) wish to comment on the parts of the document that pertain to our traditional territory: Southern Indian Lake (SIL), the Churchill River from Missi Falls to Fidler Lake and the South Bay channel down to Notigi. This territory is represented in the RCEA by Hydraulic Zones 4, 5 and 6, respectively and the South Indian and Baldock terrestrial regions. OPCN were not consulted before the approach to the RCEA was conceived and implemented by Manitoba and Manitoba Hydro. If OPCN had been, the RCEA would be a very different document because it would have addressed the changes that occurred to the environment and community because of the Churchill River Diversion in a much more substantive manner. Best practice for Cumulative Effects Assessment (CEA) recommends that analyses of changes are conducted through comparisons of states of the environment at different points in time, referred to as cases. The RCEA fails to establish a pre-development case, an immediate post- development case, a current case and reasonably foreseeable future development cases. -

The Path to Reconciliation Act ______

THE PATH TO RECONCILIATION ACT __________________ ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT PREPARED BY MANITOBA INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS DECEMBER 2020 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary: The Path to Reconciliation in Manitoba ....................................................... 3 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 7 Calls to Action: Legacies - New Initiatives....................................................................................... 8 Child Welfare .............................................................................................................................. 8 Education .................................................................................................................................... 9 Language and Culture ............................................................................................................... 11 Health ........................................................................................................................................ 12 Justice ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Calls to Action: Reconciliation - New Initiatives ........................................................................... 16 Canadian -

The Archaeology of Brabant Lake

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF BRABANT LAKE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sandra Pearl Pentney Fall 2002 © Copyright Sandra Pearl Pentney All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, In their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 5B 1) ABSTRACT Boreal forest archaeology is costly and difficult because of rugged terrain, the remote nature of much of the boreal areas, and the large expanses of muskeg. -

Public Hearings Riverlodge Place Thompson, Manitoba

National Inquiry into Enquête nationale Missing and Murdered sur les femmes et les filles Indigenous Women and Girls autochtones disparues et assassinées National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Truth-Gathering Process Part 1 Public Hearings Riverlodge Place Thompson, Manitoba PUBLIC Tuesday March 20, 2018 Public Volume 74 Rita Thomas & Mark Thomas, In Relation to Marina Spence Heard by Commissioner Michèle Audette Commission Counsel: Christa Big Canoe INTERNATIONAL REPORTING INC. 41-5450 Canotek Road, Ottawa, Ontario, K1J 9G2 E-mail: [email protected] – Phone: 613-748-6043 – Fax: 613-748-8246 II APPEARANCES Assembly of First Nations Stuart Wuttke (Legal counsel) Julie McGregor (Legal counsel) Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Non-appearance Government of Canada Lucy Bell (Legal Counsel) Government of Manitoba Samuel Thomson (Legal counsel) Manitoba Moon Voices Inc. Non-appearance MMIWG Coalition (Manitoba) Non-appearance Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Non-appearance Canada & Manitoba Inuit Association Winnipeg Police Service Non-appearance Women of the Metis Nation Non-appearance III TABLE OF CONTENTS Public Volume 74 March 20, 2018 Witnesses: Rita Thomas and Mark Thomas In Relation to Marina Spence Commissioner: Michèle Audette Commission Counsel: Christa Big Canoe Grandmothers, Elders, Knowledge-keepers: Darlene Osborne (National Family Advisory Circle), Thelma Morrisseau, Agnes Spence, Audrey Siegl, Bernie Poitras Williams, Isabelle Morris, Andy Daniels, Ovide Caribou, Florence Catcheway Clerk: Maryiam Khoury Registrar: Bryan Zandberg PAGE Testimony of Rita Thomas and Mark Thomas . 1 Reporter’s certification . 48 IV LIST OF EXHIBITS NO. DESCRIPTION PAGE No exhibits marked. Hearing - Public 1 Rita Thomas & Mark Thomas (Marina Spence) 1 Thompson, Manitoba 2 --- Upon commencing on Tuesday, March 20, 2018 at 6:01 p.m. -

Valid Operating Permits

Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality Region Number Facility 20525 WOODLANDS SHELL UST Woodlands Interlake 20532 TRAPPERS DOMO UST Alexander Eastern 55141 TRAPPERS DOMO AST Alexander Eastern 20534 LE DEPANNEUR UST La Broquerie Eastern 63370 LE DEPANNEUR AST La Broquerie Eastern 20539 ESSO - THE PAS UST The Pas Northwest 20540 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN UST Virden Western 20542 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN AST Virden Western 20545 RAMERS CARWASH AND GAS UST Beausejour Eastern 20547 CLEARVIEW CO-OP - LA BROQUERIE GAS BAR UST La Broquerie Red River 20551 FEHRWAY FEEDS AST Ridgeville Red River 20554 DOAK'S PETROLEUM - The Pas AST Gillam Northeast 20556 NINETTE GAS SERVICE UST Ninette Western 20561 RW CONSUMER PRODUCTS AST Winnipeg Red River 20562 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 29143 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 42388 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 42390 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 20563 MISERICORDIA HEALTH CENTRE AST Winnipeg Red River 20564 SUN VALLEY CO-OP - 179 CARON ST UST St. Jean Baptiste Red River 20566 BOUNDARY CONSUMERS CO-OP - DELORAINE AST Deloraine Western 20570 LUNDAR CHICKEN CHEF & ESSO UST Lundar Interlake 20571 HIGHWAY 17 SERVICE UST Armstrong Interlake 20573 HILL-TOP GROCETERIA & GAS UST Elphinstone Western 20584 VIKING LODGE AST Cranberry Portage Northwest 20589 CITY OF BRANDON AST Brandon Western 1 Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality -

Discover Canada the Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship 2 Your Canadian Citizenship Study Guide

STUDY GUIDE Discover Canada The Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship 2 Your Canadian Citizenship Study Guide Message to Our Readers The Oath of Citizenship Le serment de citoyenneté Welcome! It took courage to move to a new country. Your decision to apply for citizenship is Je jure (ou j’affirme solennellement) another big step. You are becoming part of a great tradition that was built by generations of pioneers I swear (or affirm) Que je serai fidèle before you. Once you have met all the legal requirements, we hope to welcome you as a new citizen with That I will be faithful Et porterai sincère allégeance all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. And bear true allegiance à Sa Majesté la Reine Elizabeth Deux To Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second Reine du Canada Queen of Canada À ses héritiers et successeurs Her Heirs and Successors Que j’observerai fidèlement les lois du Canada And that I will faithfully observe Et que je remplirai loyalement mes obligations The laws of Canada de citoyen canadien. And fulfil my duties as a Canadian citizen. Understanding the Oath Canada has welcomed generations of newcomers Immigrants between the ages of 18 and 54 must to our shores to help us build a free, law-abiding have adequate knowledge of English or French In Canada, we profess our loyalty to a person who represents all Canadians and not to a document such and prosperous society. For 400 years, settlers in order to become Canadian citizens. You must as a constitution, a banner such as a flag, or a geopolitical entity such as a country. -

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the Period 2002 to 2012

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the period 2002 to 2012 The following list identifies the RHAs and RHA Districts in Manitoba between the period 2002 and 2012. The 11 RHAs are listed using major headings with numbers and include the MCHP - Manitoba Health codes that identify them. RHA Districts are listed under the RHA heading and include the Municipal codes that identify them. Changes / modifications to these definitions and the use of postal codes in definitions are noted where relevant. 1. CENTRAL (A - 40) Note: In the fall of 2002, Central changed their districts, going from 8 to 9 districts. The changes are noted below, beside the appropriate district area. Seven Regions (A1S) (* 2002 changed code from A8 to A1S *) '063' - Lakeview RM '166' - Westbourne RM '167' - Gladstone Town '206' - Alonsa RM 'A18' - Sandy Bay FN Cartier/SFX (A1C) (* 2002 changed name from MacDonald/Cartier, and code from A4 to A1C *) '021' - Cartier RM '321' - Headingley RM '127' - St. Francois Xavier RM Portage (A1P) (* 2002 changed code from A7 to A1P *) '090' - Macgregor Village '089' - North Norfolk RM (* 2002 added area from Seven Regions district *) '098' - Portage La Prairie RM '099' - Portage La Prairie City 'A33' - Dakota Tipi FN 'A05' - Dakota Plains FN 'A04' - Long Plain FN Carman (A2C) (* 2002 changed code from A2 to A2C *) '034' - Carman Town '033' - Dufferin RM '053' - Grey RM '112' - Roland RM '195' - St. Claude Village '158' - Thompson RM 1 Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area -

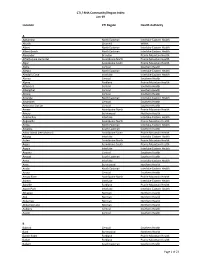

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

2010-2011 Annual Report

First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority CONTACT INFORMATION Head Office Box 10460 Opaskwayak, Manitoba R0B 2J0 Telephone: (204) 623-4472 Facsimile: (204) 623-4517 Winnipeg Sub-Office 206-819 Sargent Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba R3E 0B9 Telephone: (204) 942-1842 Facsimile: (204) 942-1858 Toll Free: 1-866-512-1842 www.northernauthority.ca Thompson Sub-Office and Training Centre 76 Severn Crescent Thompson, Manitoba R8N 1M6 Telephone: (204) 778-3706 Facsimile: (204) 778-3845 7th Annual Report 2010 - 2011 First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority—Annual Report 2010-2011 16 First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority—Annual Report 2010-2011 FIRST NATION AGENCIES OF NORTHERN MANITOBA ABOUT THE NORTHERN AUTHORITY First Nation leaders negotiated with Canada and Manitoba to overcome delays in implementing the AWASIS AGENCY OF NORTHERN MANITO- Aboriginal Justice Inquiry recommendations for First Nation jurisdiction and control of child welfare. As a result, the First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority (Northern BA Authority) was established through the Child and Family Services Authorities Act, proclaimed in November 2003. Cross Lake, Barren Lands, Fox Lake, God’s Lake Narrows, God’s River, Northlands, Oxford House, Sayisi Dene, Shamattawa, Tataskweyak, War Lake & York Factory First Nations Six agencies provide services to 27 First Nation communities and people in the surrounding areas in Northern Manitoba. They are: Awasis Agency of Northern Manitoba, Cree Nation Child and Family Caring Agency, Island Lake First Nations Family Services, Kinosao Sipi Minosowin Agency, CREE NATION CHILD AND FAMILY CARING Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation FCWC and Opaskwayak Cree Nation Child and Family Services. -

Aboriginal Place Names Rimouski: (Quebec) This Is a Word of Mi’Kmaq Or Contribute to a Rich Tapestry

Pamphlet # 24 Ontario: This Huron name, first applied to the lake, the Chipewyan people, and means "pointed skins," a may be a corruption of onitariio, meaning "beautiful Cree reference to the way the Chipewyan prepared lake," or kanadario, which translates as "sparkling" or beaver pelts. Aboriginal Peoples Contributions to "beautiful" water. Place Names in Canada Medicine Hat: (Alberta) This is a translation of the Quebec: Aboriginal peoples first used the name Blackfoot word, saamis, meaning "headdress of a 1 Provinces and Territories "kebek" for the region around Québec City. It refers medicine man." According to one explanation, the to the Algonquin word for "narrow passage" or word describes a fight between the Cree and The map of Canada is a rich tapestry of place names "strait" to indicate the narrowing of the river at Cape Blackfoot, when a Cree medicine man lost his which reflect the diverse history and heritage of our Diamond. plumed hat in the river. nation. Many of the country's earliest place names draw on Aboriginal sources. Before the arrival of Yukon: This name belonged originally to the Yukon Wetaskiwin: (Alberta) This is an adaptation of the Europeans, First Nations and Inuit peoples gave river and is from a Loucheux (Dene) word, LoYu- Cree word wi-ta-ski-oo cha-ka-tin-ow, which can be names to places throughout the country to identify kun-ah, meaning "great river." translated as "place of peace" or "hill of peace." the land they knew so well and with which they had strong spiritual connections. For centuries, these Nunavut: This is the name of Canada's newest Saskatoon: (Saskatchewan) The name comes from names that described the natural features of the land, territory which came into being on April 1, 1999.