WHERE the RIVERS FLOW PHILIP J. THOMAS British Columbia Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecosystem Status and Trends Report for the Strait of Georgia Ecozone

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2010/010 Document de recherche 2010/010 Ecosystem Status and Trends Report Rapport de l’état des écosystèmes et for the Strait of Georgia Ecozone des tendances pour l’écozone du détroit de Georgie Sophia C. Johannessen and Bruce McCarter Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Institute of Ocean Sciences 9860 W. Saanich Rd. P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, B.C. V8L 4B2 This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of des écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle the day in the time frames required and the traite des problèmes courants selon les documents it contains are not intended as échéanciers dictés. Les documents qu’elle definitive statements on the subjects addressed contient ne doivent pas être considérés comme but rather as progress reports on ongoing des énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais investigations. plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit Secretariat. envoyé au Secrétariat. This document is available on the Internet at: Ce document est disponible sur l’Internet à: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas/ ISSN 1499-3848 (Printed / Imprimé) ISSN 1919-5044 (Online / En ligne) © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2010 © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights 1 Drivers of change 2 Status and trends indicators 2 1. -

TREATY 8: a British Columbian Anomaly

TREATY 8: A British Columbian Anomaly ARTHUR J. RAY N THE ANNALS OF NATIVE BRITISH COLUMBIA, 1999 undoubtedly will be remembered as the year when, in a swirl of controversy, Ithe provincial legislature passed the Nisga'a Agreement. The media promptly heralded the agreement as the province's first modern Indian treaty. Unmentioned, because it has been largely forgotten, was the fact that the last major "pre-modern" agreement affecting British Columbia -Treaty 8 - had been signed 100 years earlier. This treaty encompasses a sprawling 160,900-square-kilometre area of northeastern British Columbia (Map 1), which is a territory that is nearly twenty times larger than that covered by the Nisga'a Agreement. In addition, Treaty 8 includes the adjoining portions of Alberta and the Northwest Territories. Treaty 8 was negotiated at a time when British Columbia vehemently denied the existence of Aboriginal title or self-governing rights. It therefore raises two central questions. First, why, in 1899, was it ne cessary to bring northeastern British Columbia under treaty? Second, given the contemporary Indian policies of the provincial government, how was it possible to do so? The latter question raises two other related issues, both of which resurfaced during negotiations for the modern Nisga'a Agreement. The first concerned how the two levels of government would share the costs of making a treaty. (I will show that attempts to avoid straining federal-provincial relations over this issue in 1899 created troublesome ambiguities in Treaty 8.) The second concerned how much BC territory had to be included within the treaty area. -

Wapiti River Water Management Plan Summary

Wapiti River Water Management Plan Summary Wapiti River Water Management Plan Steering Committee February 2020 Summary The Wapiti River basin lies within the larger Smoky/Wapiti basin of the Peace River watershed. Of all basins in the Peace River watershed, the Wapiti basin has the highest concentration and diversity of human water withdrawals and municipal and industrial wastewater discharges. The Wapiti River Water Management Plan (the Plan) was developed to address concerns about water diversions from the Wapiti River, particularly during winter low-flow periods and the potential negative impacts to the aquatic environment. In response, a steering committee of local stakeholders including municipalities, Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation, industry, agriculture, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Mighty Peace Watershed Alliance (MPWA), supported by technical experts from Alberta Environment and Parks (AEP), was established. The steering committee initiated the development of a water management plan that includes a Water Conservation Objective (WCO) and management recommendations for the Wapiti River basin from the British Columbia border to its confluence with the Smoky River. A WCO is a limit to the volume of water that can be withdrawn from the Wapiti River, ensuring that water flow remains in the river system to meet ecological objectives. The Plan provides guidance and recommendations on balancing the needs of municipal water supply, industry uses, agriculture and other uses, while maintaining a healthy aquatic ecosystem in the Alberta portion of the Wapiti River basin. Wapiti River Water Management Plan | Summary 2 Purpose and Objectives of the Plan The Plan will be provided as a recommendation to AEP and if adopted, would form policy when making water allocation decisions under the Water Act, and where appropriate, under the Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act by establishing a WCO for the Wapiti River. -

Prehistoric Mobile Art from the Mid-Fraser and Thompson River Areas ARNOUDSTRYD

CHAPTER9 Prehistoric Mobile Art from the Mid-Fraser and Thompson River Areas ARNOUDSTRYD he study of ethnographic and archaeological art the majority of archaeological work in the Plateau but from interior British Columbia has never received also appear to be the "heartland" of Plateau art develop Tthe attention which has been lavished on the art of ment as predicted by Duff (1956). Special attention will be the British Columbia coast. This was inevitable given the focused on the previously undescribed carvings recovered impressive nature of coastal art and the relative paucity in recent excavations by the author along the Fraser River of its counterpart. Nevertheless, some understanding of near the town of Lillooet. the scope and significance of this art has been attained, Reports and collections from seventy-one archaeologi largely due to the turn of the century work by members cal sites were checked for mobile art. They represent all of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition (Teit 1900, 1906, the prehistoric sites excavated and reported as of Spring 1909; Boas, 1900; Smith, 1899, 1900) and the more recent 1976, although some unintentional omissions may have studies by Duff (1956, 1975). Further, archaeological occurred. The historic components of continually oc excavations over the last fifteen years (e.g., Sanger 1968a, cupied sites were deleted and sites with assemblages of 1968b, 1970; Stryd 1972, 1973) have shown that prehistoric less than ten artifacts were also omitted. The most notable Plateau art was more extensive than previously thought, exclusions from this study are most of Smith's (1899) and that ethnographic carving represented a degeneration Lytton excavation data which are not quantified or listed from a late prehistoric developmental climax. -

Spring Bloom in the Central Strait of Georgia: Interactions of River Discharge, Winds and Grazing

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 138: 255-263, 1996 Published July 25 Mar Ecol Prog Ser I l Spring bloom in the central Strait of Georgia: interactions of river discharge, winds and grazing Kedong yinl,*,Paul J. Harrisonl, Robert H. Goldblattl, Richard J. Beamish2 'Department of Oceanography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 124 'pacific Biological Station, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Nanaimo, British Columbia, Canada V9R 5K6 ABSTRACT: A 3 wk cruise was conducted to investigate how the dynamics of nutrients and plankton biomass and production are coupled with the Fraser River discharge and a wind event in the Strait of Georgia estuary (B.C.,Canada). The spring bloom was underway in late March and early Apnl, 1991. in the Strait of Georgia estuary. The magnitude of the bloom was greater near the river mouth, indicat- ing an earher onset of the spring bloom there. A week-long wind event (wind speed >4 m S-') occurred during April 3-10 The spring bloom was interrupted, with phytoplankton biomass and production being reduced and No3 in the surface mixing layer increasing at the end of the wind event. Five days after the lvind event (on April 15),NO3 concentrations were lower than they had been at the end of the wind event, Indicating a utilization of NO3 during April 10-14. However, the utilized NO3 did not show up in phytoplankton blomass and production, which were lower than they had been at the end (April 9) of the wind event. During the next 4 d, April 15-18, phytoplankton biomass and production gradu- ally increased, and No3 concentrations in the water column decreased slowly, indicating a slow re- covery of the spring bloom Zooplankton data indicated that grazing pressure had prevented rapid accumulation of phytoplankton biomass and rapid utilization of NO3 after the wind event and during these 4 d. -

Examining Controls on Peak Annual Streamflow And

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 2285–2309, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-2285-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Examining controls on peak annual streamflow and floods in the Fraser River Basin of British Columbia Charles L. Curry1,2 and Francis W. Zwiers1 1Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium, University of Victoria, Victoria, V8N 5L3, Canada 2School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of Victoria, Victoria, V8N 5L3, Canada Correspondence: Charles L. Curry ([email protected]) Received: 26 August 2017 – Discussion started: 8 September 2017 Revised: 19 February 2018 – Accepted: 14 March 2018 – Published: 16 April 2018 Abstract. The Fraser River Basin (FRB) of British Columbia with APF of ρO D 0.64; 0.70 (observations; VIC simulation)), is one of the largest and most important watersheds in west- the snowmelt rate (ρO D 0.43 in VIC), the ENSO and PDO ern North America, and home to a rich diversity of biologi- indices (ρO D −0.40; −0.41) and (ρO D −0.35; −0.38), respec- cal species and economic assets that depend implicitly upon tively, and rate of warming subsequent to the date of SWEmax its extensive riverine habitats. The hydrology of the FRB is (ρO D 0.26; 0.38), are the most influential predictors of APF dominated by snow accumulation and melt processes, lead- magnitude in the FRB and its subbasins. The identification ing to a prominent annual peak streamflow invariably oc- of these controls on annual peak flows in the region may be curring in May–July. -

February 10, 2010 the Valley Voice 1

February 10, 2010 The Valley Voice 1 Volume 19, Number 3 February 10, 2010 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Published bi-weekly. “Your independently owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys.” WE Graham and Winlaw Schools under review for closure or re-configuration by Jan McMurray The estimated savings of closing move the VWP to Mt. Sentinel. near Castlegar that was closed, but kindergarteners, and said she hoped School District No. 8’s board Winlaw School is $64,000. In this Campbell answered, “Anything is the funding was still coming in and parents would ask board members to of education will decide the fate of scenario, it was assumed that all possible.” there were still community programs consider this in their decision. Winlaw and WE Graham Schools kids from the two communities Another concern if WEG running at the school. Ahead of the February 16 on April 13, as part of the district’s would go to WEG, although it was closes is the fate of WE Graham Former Slocan Valley school meeting at WEG, parents are asked ongoing review of its facilities. acknowledged that some parents Community Service Society. The trustee, Penny Tees, commented to submit their ideas in writing to the At a public meeting in Winlaw would choose to send their children society gets some of its funding from that busing was at the core of the district office in Nelson, or to book on February 1, the board and some south to Brent Kennedy. The 7/8 the school district because WEG has three options. -

PEACE RIVER REGIONAL DISTRICT South Peace Fringe Area Official Community Plan

PEACE RIVER REGIONAL DISTRICT South Peace Fringe Area Official Community Plan Bylaw No. 2048, 2012 Peace River Regional District Bylaw No. 2048, 2012 A bylaw to adopt an Official Community Plan for the South Peace Fringe Area to help guide future development WHEREAS Section 876 of the Local Government Act authorizes a local government to adopt an Official Community Plan to guide decisions of the Peace River Regional District on planning and land use management issues; AND WHEREAS the Regional Board has provided one or more opportunities for consultation with persons, organizations and authorities it considers affected in the development of the Official Community Plan in accordance with Section 879 of the Local Government Act; AND WHEREAS the goals reflect the resident visions relating to their community, economy and environment; AND WHEREAS the Regional Board has consulted with the Electoral Area Representatives of the Regional District; AND WHEREAS the Regional Board in accordance with Section 882 of the Local Government Act, has considered the Plan in conjunction with its capital expenditure program, solid waste management plan and has referred the Plan to the Provincial Agricultural Land Commission; AND WHEREAS in accordance with Section 875 of the Local Government Act, this Official Community Plan works towards achieving the purpose and goals referred to in Section 849 of the Local Government Act, as applicable within the Official Community Plan; NOW THEREFORE the Regional Board of the Peace River Regional District in open meeting assembled enacts as follows: 1. This bylaw shall be cited for all purposes as the “South Peace Fringe Area Official Community Plan Bylaw No. -

Columbia River Treaty History and 2014/2024 Review

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers • Bonneville Power Administration Columbia River Treaty History and 2014/2024 Review 1 he Columbia River Treaty History of the Treaty T between the United States and The Columbia River, the fourth largest river on the continent as measured by average annual fl ow, Canada has served as a model of generates more power than any other river in North America. While its headwaters originate in British international cooperation since 1964, Columbia, only about 15 percent of the 259,500 square miles of the Columbia River Basin is actually bringing signifi cant fl ood control and located in Canada. Yet the Canadian waters account for about 38 percent of the average annual volume, power generation benefi ts to both and up to 50 percent of the peak fl ood waters, that fl ow by The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River countries. Either Canada or the United between Oregon and Washington. In the 1940s, offi cials from the United States and States can terminate most of the Canada began a long process to seek a joint solution to the fl ooding caused by the unregulated Columbia provisions of the Treaty any time on or River and to the postwar demand for greater energy resources. That effort culminated in the Columbia River after Sept.16, 2024, with a minimum Treaty, an international agreement between Canada and the United States for the cooperative development 10 years’ written advance notice. The of water resources regulation in the upper Columbia River U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Basin. -

Modelling Behaviour of the Salt Wedge in the Fraser River and Its Relationship with Climate and Man-Made Changes

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Modelling Behaviour of the Salt Wedge in the Fraser River and Its Relationship with Climate and Man-Made Changes Albert Tsz Yeung Leung 1,*, Jim Stronach 1 and Jordan Matthieu 2 1 Tetra Tech Canada Inc., Water and Marine Engineering Group, 1000-10th Floor 885 Dunsmuir Street, Vancouver, BC V6C 1N5, Canada; [email protected] 2 WSP, Coastal, Ports and Maritime Engineering, 1600-René-Lévesque O., 16e étage, Montreal, QC H3H 1P9, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-604-644-9376 Received: 20 September 2018; Accepted: 3 November 2018; Published: 6 November 2018 Abstract: Agriculture is an important industry in the Province of British Columbia, especially in the Lower Mainland where fertile land in the Fraser River Delta combined with the enormous water resources of the Fraser River Estuary support extensive commercial agriculture, notably berry farming. However, where freshwater from inland meets saltwater from the Strait of Georgia, natural and man-made changes in conditions such as mean sea level, river discharge, and river geometry in the Fraser River Estuary could disrupt the existing balance and pose potential challenges to maintenance of the health of the farming industry. One of these challenges is the anticipated decrease in availability of sufficient freshwater from the river for irrigation purposes. The main driver for this challenge is climate change, which leads to sea level rise and to reductions in river flow at key times of the year. Dredging the navigational channel to allow bigger and deeper vessels in the river may also affect the availability of fresh water for irrigation. -

The Valley Voice Is a Locally-Owned Independent Newspaper

February 22, 2012 The Valley Voice 1 Volume 21, Number 4 February 22, 2012 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Published bi-weekly. “Your independently owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys.” Ministry slaps suspension on Meadow Creek Cedar’s forest licence by Jan McMurray that the $42,000 fine and the Wiggill also explained that there rather than allowing Meadow Creek for Meadow Creek Cedar. An FPB Meadow Creek Cedar (MCC) remediation order to reforest the is one exception to the company’s Cedar to seize the logs in the bush.” spokesperson reported that the has been given notice that its forest six blocks relate directly to the licence suspension. Operations on He added that if logs are left in the investigation of that complaint is licence is suspended as of February silviculture contravention found in a cutblock in the Trout Lake area, bush too long, there is a vulnerability nearing completion. FPB complaints 29. The company was also given the recent investigation. The decision which include a road permit, will be to spruce budworm. are completely separate from ministry a $42,000 fine for failing to meet to suspend the licence, however, was allowed to continue past the February Wiggill confirmed that some investigations. its silviculture (tree planting) made based on both current and past 29 suspension date. “This is to additional ministry investigations are In addition, many violations of obligations, and an order to have contraventions. essentially protect the interests of the ongoing involving Meadow Creek safety regulations have been found the tree planting done by August 15. -

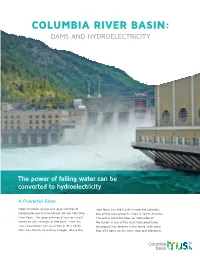

Dams and Hydroelectricity in the Columbia

COLUMBIA RIVER BASIN: DAMS AND HYDROELECTRICITY The power of falling water can be converted to hydroelectricity A Powerful River Major mountain ranges and large volumes of river flows into the Pacific—make the Columbia precipitation are the foundation for the Columbia one of the most powerful rivers in North America. River Basin. The large volumes of annual runoff, The entire Columbia River on both sides of combined with changes in elevation—from the the border is one of the most hydroelectrically river’s headwaters at Canal Flats in BC’s Rocky developed river systems in the world, with more Mountain Trench, to Astoria, Oregon, where the than 470 dams on the main stem and tributaries. Two Countries: One River Changing Water Levels Most dams on the Columbia River system were built between Deciding how to release and store water in the Canadian the 1940s and 1980s. They are part of a coordinated water Columbia River system is a complex process. Decision-makers management system guided by the 1964 Columbia River Treaty must balance obligations under the CRT (flood control and (CRT) between Canada and the United States. The CRT: power generation) with regional and provincial concerns such as ecosystems, recreation and cultural values. 1. coordinates flood control 2. optimizes hydroelectricity generation on both sides of the STORING AND RELEASING WATER border. The ability to store water in reservoirs behind dams means water can be released when it’s needed for fisheries, flood control, hydroelectricity, irrigation, recreation and transportation. Managing the River Releasing water to meet these needs influences water levels throughout the year and explains why water levels The Columbia River system includes creeks, glaciers, lakes, change frequently.