CHAPTER 3: Poles in the Austrian Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tarnobrzeski Słownik Biograficzny Wpisani W Historię Miasta TARNOBRZESKI SŁOWNIK BIOGRAFICZNY

zwedo Tarnobrzeski słownik biograficzny Wpisani w historię miasta TARNOBRZESKI SŁOWNIK BIOGRAFICZNY TOM III Bogusław Szwedo Wpisani w historię miasta TARNOBRZESKI SŁOWNIK BIOGRAFICZNY TOM III Tarnobrzeg 2016 Recenzenci: Prof. zw. dr hab. Bogusław Polak Prof. nadzw. dr hab. Czesław Partacz ©Copyright Bogusław Szwedo 2016 Projekt okładki: Joanna Ardelli/MAK Skład i łamanie: MAK Zdjęcia zamieszczone na okładce pochodzą ze zbiorów Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego i Krzysztofa Watracza z Tarnobrzega Wydawcy: Wydawnictwo ARMORYKA ul. Krucza 16 27-600 Sandomierz [email protected] www.armoryka.pl i Radio Leliwa ul. Wyspiańskiego 12 39-400 Tarnobrzeg [email protected] www.leliwa.pl ISBN 978-83-8064-154-9 ISBN 978-83-938347-3-0 5 Spis treści Wstęp....................................................................................................7 Jan Błasiak ............................................................................ 11 Jan BOCHNIAK ................................................................... 14 Kazimierz BOCHNIEWICZ ..................................... 26 Michał BUSZ ............................................................................ 29 Władysław BUSZ ................................................................. 31 Jan CZECHOWICZ ......................................................... 34 Juliusz CZECHOWICZ ................................................ 36 Karol CZECHOWICZ ................................................... 40 Tadeusz CZECHOWICZ ............................................. 43 -

![The Influence of Austrian Voting Right of 1907 on the First Electoral Law of the Successor States (Poland, Romania [Bukovina], Czechoslovakia)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0635/the-influence-of-austrian-voting-right-of-1907-on-the-first-electoral-law-of-the-successor-states-poland-romania-bukovina-czechoslovakia-190635.webp)

The Influence of Austrian Voting Right of 1907 on the First Electoral Law of the Successor States (Poland, Romania [Bukovina], Czechoslovakia)

ISSN 2411-9563 (Print) European Journal of Social Sciences May-August 2014 ISSN 2312-8429 (Online) Education and Research Volume 1, Issue 1 The influence of Austrian voting right of 1907 on the first electoral law of the successor states (Poland, Romania [Bukovina], Czechoslovakia) Dr Andrzej Dubicki Uniwersytet Łódzki Abstract As a result of collapse of the Central Powers in 1918 in Central Europe have emerged new national states e.g. Poland, Czechoslowakia, Hungaria, SHS Kingdom some of states that have existed before the Great War have changed their boundaries e.g. Romania, Bulgaria. But what is most important newly created states have a need to create their constituencies, so they needed a electoral law. There is a question in what manner they have used the solutions that have been used before the war in the elections held to the respective Parliaments (mostly to the Austrian or Hungarian parliament) and in case of Poland to the Tzarist Duma or Prussian and German Parliament. In the paper author will try to compare Electoral Laws that were used in Poland Czechoslowakia, and Romania [Bukowina]. The first object will be connected with the question in what matter the Austrian electoral law have inspired the solutions used in respective countries after the Great War. The second object will be connected with showing similarities between electoral law used in so called opening elections held mainly in 1919 in Austria-Hungary successor states. The third and final question will be connected with development of the electoral rules in respective countries and with explaining the reasons for such changes and its influence on the party system in respective country: multiparty in Czechoslovakia, hybrid in Romania. -

Issue 9 W Inter 2002 50P -- Seems to Have Been a Rather Sleepy Room Œ and Suggested It Might Be —Put in a Figure

AP Society Newsletter '9 9Deliver this to SENH,-SE, Roger Aksakov, Montaigne and The ,9 ord The Anthony Powell Society I prithee post.an debonair 1ooks o French, 6er.an and Italian He is the handso.e upstairs lodger 4erse. Po ell also came across an Newsletter At No. 10 1runswick S2uareB autographed copy of Stendhal/s book on Italian Painting on the shelves in this Issue 9 W inter 2002 50p 77 seems to have been a rather sleepy room - and suggested it might be 9put in a figure. One of the Library Committee, closed case.B A Hero of Our Club œ Anthony the height, or depth, of the ,lit8, a Captain Aennedy appears to have been a Powell at The Travellers 1930- back oodsman lumbered across to the dedicated follo er of the Turf and pressed After all his hard ork in improving the 2000: Part Two Marshall/s solitary table. for the scarce Library funds to be applied Library, Po ell as a natural choice as to buying form7guides and 3ho‘s 3ho in Chairman of the Library Committee from 9Ah, Portal, there you are! I hear Racing. Then, in Covember 194D, 6arold :une 1949 on ards. In the autumn of The edited text of a talk delivered at the Royal Flying Corps have been Cicolson, Alan Pryce7:ones, LE :ones 1951 he presented a first edition copy of A The Travellers Club, 04 March 2002 doin‘ right ully well. Keep up the Eauthor of that evocative trilogy, A :uestion o -pbringing to the club Ehe good work!$ 4ictorian 1oyhood, Edwardian 5outh and had earlier presented some of his pre7 ar by Hugh Massingberd 6eorgian A ternoonF and a certain 9A2 novels, as ell as John Aubrey and His [Part One of this talk as published in the After the ar, The Travellers/ Library Po ellB ere brought in 9to ginger things Friends in 1949F and this coincided ith Autumn 2002 Newsletter] regarded by many, including :ohn upB, as Po ell ould have put it. -

Kariery Urzędnicze I Parlamentarne Żółkiewskich Herbu Lubicz W XVI–XVII Wieku

9 WSCHODNI ROCZNIK HUMANISTYCZNY TOM XVI (2019), No 2 s. 9-27 doi: 10.36121/pjusiak.16.2019.2.009 Paweł Jusiak (Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej) ORCID 0000-0001-6933-1869 Kariery urzędnicze i parlamentarne Żółkiewskich herbu Lubicz w XVI–XVII wieku Streszczenie: Ważnym czynnikiem ukazującym znaczenie rodziny w społeczeństwie szlacheckim była służba publiczna, czyli pełnienie urzędów i sprawowanie funkcji parla- mentarnych. Należy bowiem pamiętać, że piastowanie urzędów, nawet tych najniższych, dawało szlachcicowi powagę i splendor. Żółkiewscy wywodzący się z Żółkwi koło Krasne- gostawu w ziemi chełmskiej w XV i XVI wieku zabiegali i sięgali po urzędy na które mia- ła wpływ szlachta mieszkająca w najbliższym sąsiedztwie ich siedzib. Cieszyli się wśród nich prestiżem i uznaniem. Pozwala to zaliczyć rodzinę Żółkiewskich do elity urzędniczej o znaczeniu regionalnym, związanej z konkretną ziemią w tym przypadku głównie chełm- ską oraz bełską. Tylko trzem reprezentantom Żółkiewskich udało się sięgnąć po urzędy w innych częściach Rusi Czerwonej a jedynie dwóch zdołało objąć urzędy senatorskie. Naj- większą karierę zrobił Stanisław Żółkiewski, kanclerz i hetman wielki koronny, zarazem najbardziej znany reprezentant rodu. Słowa kluczowe: Żółkiewscy, urzędnik, kariera, ziemia chełmska, poseł, żołnierz The clerical and parliamentary careers of the Żółkiewski family of the Lubicz coat of arms in the 16th–17th centuries Annotation: Public service, i.e. holding office and exercising parliamentary functions, was an important factor in showing the importance of the family in nobility society. It should be remembered that holding offices, even the lowest ones, gave the nobleman seriousness and splendour. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Żółkiewski family, coming from Żółkiew near Krasnystaw in the Chełm land, tried and occupied offices which were influenced by nobility living in the immediate vicinity of their seats. -

Factsheet: the Austrian Federal Council

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Austrian Federal Council 1. At a glance Austria is a federal republic and a parliamentary democracy. The Austrian Parliament is a bicameral body composed of the National Council (Nationalrat) and the Federal Council (Bundesrat). The 61 Members of the Federal Council are delegated by the nine regional parliaments (Landtage) and represent the interests of the regions (Länder) in the federal legislative process. They need not necessarily be Members of the regional parliament that delegates them, but they must in principle be eligible to run for elections in that region. The overall number of Members of the Federal Council is linked to the population size of the regions. The biggest region delegates twelve, the smallest at least three members. The Presidency of the Federal Council rotates every six months between the nine regions in alphabetic order. It is awarded to the Federal Council Member who heads the list of Members established by her or his region. In most cases, the National Council issues federal legislation in conjunction with the Federal Council. However, with some rare exceptions the Federal Council only has a so-called “suspensive” veto right. The National Council can override a challenge by the Federal Council to one of its resolutions by voting on the resolution again. 2. Composition Composition of the Austrian Federal Council Party EP affiliation Seats Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) Austrian People's Party 25 Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) Social Democratic Party of Austria 19 Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) Freedom Party of Austria 11 Die Grünen 5 The Greens NEOS 1 61 3. -

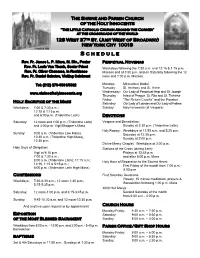

Schedule Rev

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Founded 1866 Schedule Rev. Fr. James L. P. Miara, M. Div., Pastor Perpetual Novenas Rev. Fr. Louis Van Thanh, Senior Priest Weekdays following the 7:30 a.m. and 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Rev. Fr. Oliver Chanama, In Residence Masses and at 5:50 p.m. and on Saturday following the 12 Rev. Fr. Daniel Sabatos, Visiting Celebrant noon and 1:00 p.m. Masses. Tel: (212) 279-5861/5862 Monday: Miraculous Medal Tuesday: St. Anthony and St. Anne www.shrineofholyinnocents.org Wednesday: Our Lady of Perpetual Help and St. Joseph Thursday: Infant of Prague, St. Rita and St. Thérèse Friday: “The Return Crucifix” and the Passion Holy Sacrifice of the Mass Saturday: Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima Weekdays: 7:00 & 7:30 a.m.; Sunday: Holy Innocents (at Vespers) 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Devotions Saturday: 12 noon and 1:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Vespers and Benediction: and 4:00 p.m. Vigil/Shopper’s Mass Sunday at 2:30 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Holy Rosary: Weekdays at 11:55 a.m. and 5:20 p.m. Sunday: 9:00 a.m. (Tridentine Low Mass), Saturday at 12:35 p.m. 10:30 a.m. (Tridentine High Mass), Sunday at 2:00 p.m. 12:30 p.m. Divine Mercy Chaplet: Weekdays at 3:00 p.m. -

Professional and Ethical Standards for Parliamentarians Background Study: Professional and Ethical Standards for Parliamentarians

Background Study: Professional and Ethical Standards for Parliamentarians Background Study: Professional and Ethical Standards for Parliamentarians Warsaw, 2012 Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul. Miodowa 10, 00–251 Warsaw, Poland http://www.osce.org/odihr © OSCE/ODIHR 2012, ISBN 978–92–9234–844–1 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the OSCE/ODIHR as the source. Designed by Homework Cover photo of the Hungarian Parliament Building by www.heatheronhertravels.com. Printed by AGENCJA KARO Table of contents Foreword 5 Executive Summary 8 Part One: Preparing to Reform Parliamentary Ethical Standards 13 1.1 Reasons to Regulate Conduct 13 1.2 The Limits of Regulation: Private Life 19 1.3 Immunity for Parliamentarians 20 1.4 The Context for Reform 25 Part Two: Tools for Reforming Ethical Standards 31 2.1 A Code of Conduct 34 2.2 Drafting a Code 38 2.3 Assets and Interests 43 2.4 Allowances, Expenses and Parliamentary Resources 49 2.5 Relations with Lobbyists 51 2.6 Other Areas that may Require Regulation 53 Part Three: Monitoring and Enforcement 60 3.1 Making a Complaint 62 3.2 Investigating Complaints 62 3.3 Penalties for Misconduct 69 3.4 Administrative Costs 71 3.5 Encouraging Compliance 72 3.6 Updating and Reviewing Standards 75 Conclusions 76 Glossary 79 Select Bibliography 81 Foreword The public accountability and political credibility of Parliaments are cornerstone principles, to which all OSCE participating States have subscribed. -

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Ivana Bago 2018 Abstract The dissertation examines the work contemporary artists, curators, and scholars who have, in the last two decades, addressed urgent political and economic questions by revisiting the legacies of the Yugoslav twentieth century: multinationalism, socialist self-management, non- alignment, and -

01-067 Foff Fed Eng News

Federations What’s new in federalism worldwide volume 1, number 5, summer 2001 In this issue Is Europe heading towards a federal constitution? By Uwe Leonardy After German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer gave a controversial speech last year arguing for a more federal Europe, other leaders have now joined the debate about the value of a federal constitution for the expanding EU. The member states have already ceded some powers to the EU—how much more sovereignty are they willing to give up? State elections foretell a power shift at India’s centre By Prasenjit Maiti The state elections in May showed that, more than ever before, India’s national political parties have to form alliances with regional parties to maintain power. Can India’s central governments pursue a coherent agenda if they are beholden to this plurality of local interests? Education reform, school vouchers and privatization in the USA By Bill Berkowitz Education is President George W. Bush’s “marquee” issue. He made educational reforms the centrepiece of his governorship and of his election campaign. But the Bill that the House of Representatives recently passed altered some of his most cherished conservative proposals. Ethiopia: the challenge of many nationalities By Hashim Tewfik Mohammed Modern Ethiopian history has been characterized by internecine wars, famine, and economic deterioration. But in the past decade, there has been a consistent move, culminating in the adoption of a new constitution, towards giving self-government to the various ethnic groups and incorporating them into a consensual federal structure. Two new initiatives for reforming aboriginal governance in Canada By Paul Barnsley Most observers agree that the Canadian federal law dealing with aboriginal peoples is an antiquated hold-over from colonial times. -

Gerard Mannion Is to Be Congratulated for This Splendid Collection on the Papacy of John Paul II

“Gerard Mannion is to be congratulated for this splendid collection on the papacy of John Paul II. Well-focused and insightful essays help us to understand his thoughts on philosophy, the papacy, women, the church, religious life, morality, collegiality, interreligious dialogue, and liberation theology. With authors representing a wide variety of perspectives, Mannion avoids the predictable ideological battles over the legacy of Pope John Paul; rather he captures the depth and complexity of this extraordinary figure by the balance, intelligence, and comprehensiveness of the volume. A well-planned and beautifully executed project!” —James F. Keenan, SJ Founders Professor in Theology Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts “Scenes of the charismatic John Paul II kissing the tarmac, praying with global religious leaders, addressing throngs of adoring young people, and finally dying linger in the world’s imagination. This book turns to another side of this outsized religious leader and examines his vision of the church and his theological positions. Each of these finely tuned essays show the greatness of this man by replacing the mythological account with the historical record. The straightforward, honest, expert, and yet accessible analyses situate John Paul II in his context and show both the triumphs and the ambiguities of his intellectual legacy. This masterful collection is absolutely basic reading for critically appreciating the papacy of John Paul II.” —Roger Haight, SJ Union Theological Seminary New York “The length of John Paul II’s tenure of the papacy, the complexity of his personality, and the ambivalence of his legacy make him not only a compelling subject of study, but also a challenging one. -

House of Lords Library Note: the Life Peerages Act 1958

The Life Peerages Act 1958 This year sees the 50th anniversary of the passing of the Life Peerages Act 1958 on 30 April. The Act for the first time enabled life peerages, with a seat and vote in the House of Lords, to be granted for other than judicial purposes, and to both men and women. This Library Note describes the historical background to the Act and looks at its passage through both Houses of Parliament. It also considers the discussions in relation to the inclusion of women life peers in the House of Lords. Glenn Dymond 21st April 2008 LLN 2008/011 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Life peerages – an historical overview .......................................................................... 2 2.1 Hereditary nature of peerage................................................................................... 2 2.2 Women not summoned to Parliament ..................................................................... 2 2.3 Early life peerages.................................................................................................. -

The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897

THE GERMAN NATIONAL ATTACK ON THE CZECH MINORITY IN VIENNA, 1897-1914, AS REFLECTED IN THE SATIRICAL JOURNAL Kikeriki, AND ITS ROLE AS A CENTRIFUGAL FORCE IN THE DISSOLUTION OF AUSTRIA-HUNGARY. Jeffery W. Beglaw B.A. Simon Fraser University 1996 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History O Jeffery Beglaw Simon Fraser University March 2004 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Jeffery Beglaw DEGREE: Master of Arts, History TITLE: 'The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897-1914, as Reflected in the Satirical Journal Kikeriki, and its Role as a Centrifugal Force in the Dissolution of Austria-Hungary.' EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Martin Kitchen Senior Supervisor Nadine Roth Supervisor Jerry Zaslove External Examiner Date Approved: . 11 Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without the author's written permission.