Interview with Dr Alison Cronin, Director of Monkey World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

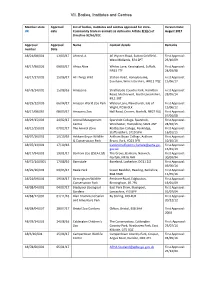

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Predator-Primate Occupation and Co-Occurrence in the Issa Valley, Katavi Region, Western Tanzania

BSc. thesis: Predator-primate occupation and co-occurrence in the Issa Valley, Katavi Region, western Tanzania. Menno J. Breider Student Applied Biology, Aeres University of Applied Sciences, Almere, The Netherlands Aeres University graduation teacher: Quirine Hakkaart In association with the Ugalla Primate Project Edam, 2 June 2017 This page is intentionally left blank for double-sided printing BSc. thesis: Predator-primate occupation and co-occurrence in the Issa Valley, Katavi Region, western Tanzania. Menno J. Breider Student Applied Biology, Aeres University of Applied Sciences, Almere, The Netherlands Aeres University graduation teacher: Quirine Hakkaart In association with the Ugalla Primate Project Edam, 2 June 2017 Front page images, top to bottom: Top: Eastern chimpanzee and leopard at the same location, different occasions. Middle: Researcher and leopard at the same location, different occasions. Bottom: Red-tailed monkey and researchers at the same location, different occasions. All: Camera trap footage from the Issa Valley, provided by the Ugalla Primate Project. Edited: combined, gradient created and cropped. This page is intentionally left blank for double-sided printing - Acknowledgements I wish to thank, first and foremost, Alex Piel of the Ugalla Primate Project for enabling this subject and for patiently supporting me during this project. His quick responses (often within an hour, no matter what time of the day), feedback and insights have been indispensable. I am also grateful to my graduation teacher, Quirine Hakkaart from the Aeres University, for guiding me through this thesis project and for her feedback on multiple versions of this study and its proposal. I would also have been unable to complete this research without the support and feedback of my friends and family. -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Gibbon Journal Nr

Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – May 2009 Gibbon Conservation Alliance ii Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – 2009 Impressum Gibbon Journal 5, May 2009 ISSN 1661-707X Publisher: Gibbon Conservation Alliance, Zürich, Switzerland http://www.gibbonconservation.org Editor: Thomas Geissmann, Anthropological Institute, University Zürich-Irchel, Universitätstrasse 190, CH–8057 Zürich, Switzerland. E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Assistants: Natasha Arora and Andrea von Allmen Cover legend Western hoolock gibbon (Hoolock hoolock), adult female, Yangon Zoo, Myanmar, 22 Nov. 2008. Photo: Thomas Geissmann. – Westlicher Hulock (Hoolock hoolock), erwachsenes Weibchen, Yangon Zoo, Myanmar, 22. Nov. 2008. Foto: Thomas Geissmann. ©2009 Gibbon Conservation Alliance, Switzerland, www.gibbonconservation.org Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – 2009 iii GCA Contents / Inhalt Impressum......................................................................................................................................................................... i Instructions for authors................................................................................................................................................... iv Gabriella’s gibbon Simon M. Cutting .................................................................................................................................................1 Hoolock gibbon and biodiversity survey and training in southern Rakhine Yoma, Myanmar Thomas Geissmann, Mark Grindley, Frank Momberg, Ngwe Lwin, and Saw Moses .....................................4 -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Slow Loris Finds Itself Stranded April 30Th 2016

Slow loris finds itself stranded far away from home... at Yishun carpark PHOTO: YouTube screengrabs ASIAONE Apr 30, 2016 SINGAPORE - It has a permanent look of surprise on its face, but this slow loris was probably really afraid when it found itself surrounded by a concrete jungle instead of the lush greenery she is used to. Earlier this month, officers from the Animal Concerns Research & Education Society (Acres) were notified of a slow loris stranded in a multi-storey carpark at Yishun Central. The resident who found the nocturnal animal recognised it immediately and knew that it was not in a place it belonged. One of Singapore's critically endangered creatures, slow lorises are usually found deep in the nature reserves of Singapore where they enjoy a diet of fruit, sap, nectar, bird eggs and insects. In a video uploaded on Acres' YouTube account, the slow loris can be seen perched on the ledge three storeys above ground. With thick gloves to protect himself from the the animal's strong and toxic bite, an Acres officer grabs hold of it and brings it carefully to safety. Manager of Acres' wildlife department, Kalai, told AsiaOne in a phone interview that the Sunda slow loris, which is native to Singapore, is usually not found near residential areas. So how exactly did this "young adult" female slow loris get to a carpark in Yishun Central? Kalai says there are just two possible scenarios. One possibility was that it had been sold as part of the illegal pet trade and escaped from captivity, while the other possibility was that it could have accidentally 'hitched' a ride out of the nature reserve on the car of an unsuspecting visitor. -

Distribution and Conservation Status of the Vulnerable Eastern Hoolock

Distribution and conservation status of the Vulnerable eastern hoolock gibbon Hoolock leuconedys in China F an P eng-Fei,Xiao W en,Huo S heng,Ai H uai-Sen,Wang T ian-Can and L in R u-Tao Abstract We conducted an intensive survey of the Vul- Several recent studies have described the eastern hoolock nerable eastern hoolock gibbon Hoolock leuconedys along gibbon populations outside China. Das et al. (2006)identi- the west bank of the Salween River in southern China, fied the eastern species for the first time in the Lohit district covering all known hoolock gibbon populations in China. of Arunachal Pradesh in India. Chetry et al. (2008) found an We found 40–43 groups, with a mean group size of 3.9, additional 150 groups between Dibang and Lohit in Aruna- and five solitary individuals. We estimated the total chal Pradesh, India. Brockelman et al. (2009) estimated the population to be , 200. In the nine groups for which we population size in Mahamyaing Wildlife Sanctuary in recorded composition, seven comprised one adult pair and Myanmar to be c. 5,900.Walkeretal.(2009) estimated that 0–3 offspring and the other two groups both comprised the Hukaung Valley Reserve in northern Myanmar could one adult male and two adult females. The population is support tens of thousands of eastern hoolock gibbons, severely fragmented, in 17 locations, with the largest sub- potentially the largest population in the world. population containing only five family groups. Compared No recent data are available on the current distribution, with the population in 1985 and 1994 five subpopulations status and population size of H. -

Sexual Selection in the Ring-Tailed Lemur (Lemur Catta): Female

Copyright by Joyce Ann Parga 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Joyce Ann Parga certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Sexual Selection in the Ring-tailed Lemur (Lemur catta): Female Choice, Male Mating Strategies, and Male Mating Success in a Female Dominant Primate Committee: Deborah J. Overdorff, Supervisor Claud A. Bramblett Lisa Gould Rebecca J. Lewis Liza J. Shapiro Sexual Selection in the Ring-tailed Lemur (Lemur catta): Female Choice, Male Mating Strategies, and Male Mating Success in a Female Dominant Primate by Joyce Ann Parga, B.S.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2006 Dedication To my grandfather, Santiago Parga Acknowledgements I would first like to thank the St. Catherines Island Foundation, without whose cooperation this research would not have been possible. The SCI Foundation graciously provided housing and transportation throughout the course of this research. Their aid is gratefully acknowledged, as is the permission to conduct research on the island that I was granted by the late President Frank Larkin and the Foundation board. The Larkin and Smith families are also gratefully acknowledged. SCI Superintendent Royce Hayes is thanked for his facilitation of all aspects of the field research, for his hospitality, friendliness, and overall accessibility - whether I was on or off the island. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) is also an organization whose help is gratefully acknowledged. In particular, Colleen McCann and Jim Doherty of the WCS deserve thanks. -

Sleep and Nesting Behavior in Primates: a Review

Received: 29 July 2017 | Revised: 30 November 2017 | Accepted: 2 December 2017 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.23373 REVIEW ARTICLE Sleep and nesting behavior in primates: A review Barbara Fruth1,2,3,4 | Nikki Tagg1 | Fiona Stewart2 1Centre for Research and Conservation/ KMDA, Antwerp, Belgium Abstract 2Faculty of Science/School of Natural Sleep is a universal behavior in vertebrate and invertebrate animals, suggesting it originated in the Sciences and Psychology, Liverpool John very first life forms. Given the vital function of sleep, sleeping patterns and sleep architecture fol- Moores University, United Kingdom low dynamic and adaptive processes reflecting trade-offs to different selective pressures. 3 Department of Developmental and Here, we review responses in sleep and sleep-related behavior to environmental constraints Comparative Psychology, Max-Planck- across primate species, focusing on the role of great ape nest building in hominid evolution. We Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany summarize and synthesize major hypotheses explaining the proximate and ultimate functions of 4Faculty of Biology/Department of great ape nest building across all species and subspecies; we draw on 46 original studies published Neurobiology, Ludwig Maximilians between 2000 and 2017. In addition, we integrate the most recent data brought together by University of Munich, Germany researchers from a complementary range of disciplines in the frame of the symposium “Burning the midnight oil” held at the 26th Congress of the International Primatological Society, Chicago, Correspondence Barbara Fruth, Liverpool John Moores August 2016, as well as some additional contributors, each of which is included as a “stand-alone” University, Faculty of Science/NSP, article in this “Primate Sleep” symposium set. -

The Biogeography of Large Islands, Or How Does the Size of the Ecological Theater Affect the Evolutionary Play

The biogeography of large islands, or how does the size of the ecological theater affect the evolutionary play Egbert Giles Leigh, Annette Hladik, Claude Marcel Hladik, Alison Jolly To cite this version: Egbert Giles Leigh, Annette Hladik, Claude Marcel Hladik, Alison Jolly. The biogeography of large islands, or how does the size of the ecological theater affect the evolutionary play. Revue d’Ecologie, Terre et Vie, Société nationale de protection de la nature, 2007, 62, pp.105-168. hal-00283373 HAL Id: hal-00283373 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00283373 Submitted on 14 Dec 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE BIOGEOGRAPHY OF LARGE ISLANDS, OR HOW DOES THE SIZE OF THE ECOLOGICAL THEATER AFFECT THE EVOLUTIONARY PLAY? Egbert Giles LEIGH, Jr.1, Annette HLADIK2, Claude Marcel HLADIK2 & Alison JOLLY3 RÉSUMÉ. — La biogéographie des grandes îles, ou comment la taille de la scène écologique infl uence- t-elle le jeu de l’évolution ? — Nous présentons une approche comparative des particularités de l’évolution dans des milieux insulaires de différentes surfaces, allant de la taille de l’île de La Réunion à celle de l’Amé- rique du Sud au Pliocène. -

July 2018 Vol.6 No.1 Journal of Indonesian Natural History Editors Dr

Journal of Indonesian Natural History July 2018 Vol.6 No.1 Journal of Indonesian Natural History Editors Dr. Wilson Novarino Dr. Carl Traeholt Associate Professor for Biology Programme Director, Southeast Asia Department of Biology Research and Conservation Division Andalas University, Indonesia Copenhagen Zoo, Denmark Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Editorial board Dr. Ardinis Arbain Dr. Ramadhanil Pitopang University of Andalas, Indonesia Tadulako University, Indonesia Indra Arinal Dr. Lilik Budi Prasetyo National Park Management, Department of Forestry Indonesia Bogor Institute of Agriculture, Indonesia Dr. Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz Dr. Dewi Malia Prawiradilaga Nottingham University Malaysia Campus, Malaysia Indonesia Institute of Science, Indonesia Dr. Mads Frost Bertelsen Dr. Rizaldi Research and Conservation Division, Copenhagen Zoo, Denmark University of Andalas, Indonesia Dr. Susan Cheyne Dr. Dewi Imelda Roesma Oxford University, Wildlife Research Unit, United Kingdom University of Andalas, Indonesia Bjorn Dahlen Dr. Jeffrine Rovie Ryan Green Harvest Environmental Sdn. Bhd, Malaysia Wildlife Forensics Lab, Dept. of Wildlife and National Parks, Malaysia Dr. Niel Furey Boyd Simpson Centre for Biodiversity Conservation, Royal University of Phnom Penh, Cambodia Research and Conservation Division, Copenhagen Zoo, Denmark Dr. Benoit Goossens Robert B. Stuebing Cardiff University, United Kingdom Herpetology and Conservation Biology, Indonesia Dr. Djoko Iskandar Dr. Sunarto Bandung Institute of Technology, Indonesia WWF-Indonesia -

APE RESCUE CENTRE Risk Assessment for School & Group

MONKEY WORLD – APE RESCUE CENTRE Risk Assessment for School & Group Educational Visits 2020/21 Please note: We are a primate rescue and rehabilitation centre and not a zoo, as such the majority of our primates have been abused, neglected and exploited. We would be grateful if you could remind your students of this fact prior to entering our park. We have offered our rescued monkeys and apes sanctuary, free from abuse of any kind and we will not tolerate any behaviour from visitors that causes distress to our primates in anyway e.g. shouting, screaming, banging on the viewing windows, running up and down outside enclosures, throwing items into the enclosures, feeding our primates etc. Visitors that do not abide by the rules of entry to the park will be asked to leave and no refund will be given. Risk Assessment Guidance Monkey World operates under the auspices of the Zoo Licensing Act. We are subject to annual inspections from Enforcement Officers who look at the way we take care of our Primates and the safety of Staff and Visitors. The licence has to be renewed every six years. We strongly recommend that group organisers make a pre-visit to Monkey World and carry out their own risk assessment. We allow one free entry per class/group which is available on request when booking your visit. In the event that a pre-visit is impossible, this document provides a general outline of the risks and controls identified. It is essential that all children are supervised throughout their visit to us and that all attending the visit understand the following: the aims and objectives of the visit how to avoid specific dangers and why they must follow rules why safety precautions are in place and standard of behaviour is expected who is responsible for the Group what to do if approached by anyone outside the Group what to do if separated from the Group the time and place of departure of the Group that in an emergency situation e.g.