Planning for Natural Heritage: Planning Advice Note 60

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burns Chronicle 1941

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1941 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Dr Hugh Mackay and Mrs Valerie Mackay of Leicester Caledonian Society The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 189 1 PUBLIBHED ANNUALLY SECOND SERIES : VOLUME XVI THE BURNS FEDERATION KILMARNOCK 1941 Price Three shillings * "BURNS OHRONICLE" ADVERTISER "0 what a glorious sight, warm-reekln'. rich I"-BURNS WAUGH'S SCOTCH HAGGIS Delicious-Appetising-Finely Flavoured. Made from a recipe that has no equal for Quality. A wholesome meal for the Family . On the menu of every imJ)ortant Scottish function-St. Andrew's · Day, Burns Anniversary, &c., &c.-at home and abroad. Per 1/4 lb. Also in hermetically sealed tins for export 1 lb. 2/· 2 lbs. 3/6 3 lbs. 5/· (plus post) Always book your orders early for these dates ST. ANDREW'S DAY CHRISTMAS DAY November 30 December 25 HOGMANAY BURNS ANNIVERSARY December31 Janual'J 25 Sole Maker Cooked In Che model ldcchens at Hoalscon GEORGE WAUGH 110 NICOLSON STREET, EDINBURGH, 8 SCOTLAND Telephone 42849 Telegrams and Cables: "HAGGIS" ; "BURNS CHRONICLE ADVERTISER" NATIONAL BURNS MEMORIAL COTTAGE HOMES, MAUCHLINE, AYRSHIRE. In Memory of the Poet Burns for Deserving Old People. "That greatest of benevolent Institutions established In honour of Robert Burns." -9/o.igo• H,,a/d. There are now twenty modern comfortable houses for the benefit of deserving old folks. -

Early Learning and Childcare Funded Providers 2019/20

Early Learning and Childcare Funded Providers 2019/20 LOCAL AUTHORITY NURSERIES NORTH Abronhill Primary Nursery Class Medlar Road Jane Stocks 01236 794870 [email protected] Abronhill Cumbernauld G67 3AJ Auchinloch Nursery Class Forth Avenue Andrew Brown 01236 794824 [email protected] Auchinloch Kirkintilloch G66 5DU Baird Memorial PS SEN N/Class Avonhead Road Gillian Wylie 01236 632096 [email protected] Condorrat Cumbernauld G67 4RA Balmalloch Nursery Class Kingsway Ruth McCarthy 01236 632058 [email protected] Kilsyth G65 9UJ Carbrain Nursery Class Millcroft Road Acting Diane Osborne 01236 794834 [email protected] Carbrain Cumbernauld G67 2LD Chapelgreen Nursery Class Mill Road Siobhan McLeod 01236 794836 [email protected] Queenzieburn Kilsyth G65 9EF Condorrat Primary Nursery Class Morar Drive Julie Ann Price 01236 794826 [email protected] Condorrat Cumbernauld G67 4LA Eastfield Primary School Nursery 23 Cairntoul Court Lesley McPhee 01236 632106 [email protected] Class Cumbernauld G69 9JR Glenmanor Nursery Class Glenmanor Avenue Sharon McIlroy 01236 632056 [email protected] Moodiesburn G69 0JA Holy Cross Primary School Nursery Constarry Road Marie Rose Murphy 01236 632124 [email protected] Class Croy Kilsyth G65 9JG Our Lady and St Josephs Primary South Mednox Street Ellen Turnbull 01236 632130 [email protected] School Nursery Class Glenboig ML5 2RU St Andrews Nursery Class Eastfield Road Marie Claire Fiddler -

CONTACT LIST.Xlsx

Valuation Appeal Hearing: 13th March 2019 Contact list Property ID ST A Street Locality Description Appealed NAV Appealed RV Agent Name Appellant Name Contact Contact Number No. 39 DEERDYKES VIEW CUMBERNAULD WORKSHOP £16,300 £16,300 ASPEX SCOTLAND LTD CHRISTINE MAXWELL 01698 476053 38 GARRELL ROAD KILSYTH BATCHING PLANT £18,700 £18,700 BANNERMAN COMPANY LIMITED ROSS WILSON 01698 476061 VALLEYBANK 43 BANTON KILSYTH FACTORY £27,000 £27,000 J B BENNETT (CONTRACTS) LTD ROSS WILSON 01698 476061 UNIT 6 5 FOUNDRY ROAD SHOTTS ABATTOIR £30,250 £30,250 JAMES CHAPMAN ( BUTCHERS) LTD ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 131 DEERDYKES VIEW CUMBERNAULD WAREHOUSE £15,200 £15,200 M G H RECLAIM CHRISTINE MAXWELL 01698 476053 375 LANGMUIR ROAD BARGEDDIE BAILLIESTON WORKSHOP £100,000 £100,000 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 STRATHCLYDE BUSINESS CTRE 391 LANGMUIR ROAD BARGEDDIE BAILLIESTON STORE £1,000 £1,000 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 STRATHCLYDE BUSINESS CTRE 391 LANGMUIR ROAD BARGEDDIE BAILLIESTON STORE £1,000 £1,000 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 STRATHCLYDE BUSINESS CTRE 391 LANGMUIR ROAD BARGEDDIE BAILLIESTON STORE £7,200 £7,200 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 STRATHCLYDE BUSINESS CTRE 391 LANGMUIR ROAD BARGEDDIE BAILLIESTON WORKSHOP £8,500 £8,500 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 STRATHCLYDE BUSINESS CTRE 391 LANGMUIR ROAD BARGEDDIE BAILLIESTON STORE £3,150 £3,150 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 STRATHCLYDE BUSINESS CTRE 391 LANGMUIR ROAD BARGEDDIE -

Notices and Proceedings for Scotland

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER SCOTLAND NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2199 PUBLICATION DATE: 22/10/2018 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 12/11/2018 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Scotland) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 29/10/2018 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to bus registrations and public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Scotland) Level 6 The Stamp Office 10 Waterloo Place Edinburgh EH1 3EG The public counter in Edinburgh is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. Please note that only payments for bus registration applications can be made at this counter. The telephone number for bus registration enquiries is 0131 200 4927. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. -

276 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

276 bus time schedule & line map 276 Bathgate View In Website Mode The 276 bus line (Bathgate) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bathgate: 5:20 AM - 5:07 PM (2) Broxburn: 6:07 AM - 10:32 PM (3) Livingston: 10:30 PM (4) Loganlea: 6:37 AM - 9:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 276 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 276 bus arriving. Direction: Bathgate 276 bus Time Schedule 81 stops Bathgate Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:20 AM - 5:07 PM Dunnet Way, Broxburn Hunter Gardens, Broxburn Tuesday 5:20 AM - 5:07 PM Thistle Business Park, Broxburn Wednesday 5:20 AM - 5:07 PM Aitken Orr Drive, Broxburn Thursday 5:20 AM - 5:07 PM East Main Street, Broxburn Friday 5:20 AM - 5:07 PM Aitken Orr Drive, Broxburn Saturday 7:07 AM - 5:07 PM Church Street, Broxburn 91-95 East Main Street, Broxburn Post O∆ce, Broxburn 276 bus Info Direction: Bathgate New Holygate, Broxburn Stops: 81 New Holygate, Broxburn Trip Duration: 84 min Line Summary: Dunnet Way, Broxburn, Thistle Kirkhill Road, Broxburn Business Park, Broxburn, Aitken Orr Drive, Broxburn, Aitken Orr Drive, Broxburn, Church Street, Broxburn, Cardross Road, Broxburn Post O∆ce, Broxburn, New Holygate, Broxburn, West Main Street, Broxburn Kirkhill Road, Broxburn, Cardross Road, Broxburn, Cardross Road, Broxburn, Freeland Avenue, Cardross Road, Broxburn Broxburn, Cemetery, Uphall, Alexander Street, Uphall, Oatridge Hotel, Uphall, St Andrews Drive, Uphall, Freeland Avenue, Broxburn Millbank Place, Uphall, Stankards -

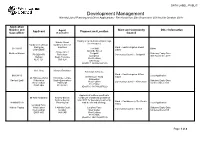

Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30Th September 2019 to 6Th October 2019

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30th September 2019 to 6th October 2019 Application Number and Ward and Community Other Information Applicant Agent Proposal and Location Case officer (if applicable) Council Display of an illuminated fascia sign Natalie Gaunt (in retrospect). Cardtronics UK Ltd, Cardtronic Service trading as Solutions Ward :- East Livingston & East 0877/A/19 The Mall Other CASHZONE Calder Adelaide Street 0 Hope Street Matthew Watson Craigshill Statutory Expiry Date: PO BOX 476 Rotherham Community Council :- Craigshill Livingston 30th November 2019 Hatfield South Yorkshire West Lothian AL10 1DT S60 1LH EH54 5DZ (Grid Ref: 306586,668165) Ms L Gray Maxwell Davidson Extenison to house. Ward :- East Livingston & East 0880/H/19 Local Application 20 Hillhouse Wynd Calder 20 Hillhouse Wynd 19 Echline Terrace Kirknewton Rachael Lyall Kirknewton South Queensferry Statutory Expiry Date: West Lothian Community Council :- Kirknewton West Lothian Edinburgh 1st December 2019 EH27 8BU EH27 8BU EH30 9XH (Grid Ref: 311789,667322) Approval of matters specified in Mr Allan Middleton Andrew Bennie conditions of planning permission Andrew Bennie 0462/P/17 for boundary treatments, Ward :- Fauldhouse & The Breich 0899/MSC/19 Planning Ltd road details and drainage. Local Application Valley Longford Farm Mahlon Fautua West Calder 3 Abbotts Court Longford Farm Statutory Expiry Date: Community Council :- Breich West Lothian Dullatur West Calder 1st December 2019 EH55 8NS G68 0AP West Lothian EH55 8NS (Grid Ref: 298174,660738) Page 1 of 8 Approval of matters specified in conditions of planning permission G and L Alastair Nicol 0843/P/18 for the erection of 6 Investments EKJN Architects glamping pods, decking/walkway 0909/MSC/19 waste water tank, landscaping and Ward :- Linlithgow Local Application Duntarvie Castle Bryerton House associated works. -

4 Michaelson Square Kirkton Campus, Livingston Eh54 7Dp

4 MICHAELSON SQUARE KIRKTON CAMPUS, LIVINGSTON EH54 7DP OFFICE ACCOMMODATION WITH WORKSHOP SPACE TO LET / MAY SELL • 25 DEDICATED CAR PARKING SPACES • SUITES FROM 442.7 - 1,001.2 SQ M (4,766 - 10,778 SQ FT) LOCATION Dechmont Uphall Livingston is a well established office location M8 A89 Uphall Station Edinburgh benefiting from easy access to the motorway J3 New Houstoun M8 Business Park Knightsridge A899 network due to its close proximity to Junctions 3 and Industrial B8046 Estate 3a of the M8. Livingston is situated approximately 30 miles east of Glasgow city centre and 15 miles M8 Floor HOUSTON RD west of Edinburgh city centre. A705 J3a B7031 A779 B7015 B8046 4 Michaelson Square is situated within Kirkton Glasgow Campus, an established office campus to the west of LIVINGSTON Mid Calder A705 Livingston town centre. Town Centre Seafield ousland Rd 05 C Other notable occupiers in the immediate vicinity A71 A7 include BskyB, Evans Easyspace, Edinburgh Bellsquarry Instruments Limited, Alcatel Vacuum Technology and Polbeth Optocap Limited. DESCRIPTION SPECIFICATION The premises comprise a single storey, steel portal The specification of the offices include: framed constructed unit with brick blockwork walls • Gas fired central heating incorporating double glazed window units on all elevations. The roof consists of profile metal cladding • Perimeter trunking with a raised central core and a skylight to provide • Suspended ceilings incorporating acoustic tiles additional natural light to the internal areas. Part of the offices have recently undergone an extensive • CAT 2 luminaries refurbishment to a high specification. The remainder of • Kitchen facilities the building can be easily upgraded, alternatively the space offers good potential workshop accommodation. -

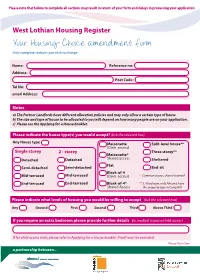

Housing Choice Amendment Form Only Complete Sections You Wish to Change

Please note that failure to complete all sections may result in return of your form and delays in processing your application West Lothian Housing Register Your Housing Choice amendment form Only complete sections you wish to change Name: Reference no: Address: Post Code: Tel No: email Address: Notes a) The Partner Landlords have different allocation policies and may only allow a certain type of house b) The size and type of house to be allocated to you will depend on how many people are on your application. c) Please see the Applying for a House Booklet. Please indicate the house type(s) you would accept? (tick the relevant box) Any House type Maisonette Split-level house** (Own access) Single storey 2 - storey Three storey** Maisonette* Detached Detached Shared access Sheltered Flat Semi-detached Semi-detached Bed-sit Block-of-4 Mid-terraced Mid-terraced (Own access) * Common access, shared stairwell End-terraced End-terraced Block-of-4* ** 3, 4 bedroom, only Almond have Shared Access this property type in Craigshill Please indicate what levels of housing you would be willing to accept (tick the relevant box) Any Ground First Second Third Above Third If you require an extra bedroom please provide further details (ie medical reasons/child access) If for child access visits, please refer to Applying for a House booklet. Proof must be provided Please Turn Over a partnership between... What heating type would you accept? (tick the relevant box) Any Gas Electric Coal Please tick the areas below for which you would wish to be considered Any -

Proposed Plan – Period for Representations

PROPOSED PLAN – PERIOD FOR REPRESENTATIONS 7 NOVEMBER 2011 – 19 DECEMBER 2011 Form P3 – Submission of Representations The Proposed Plan has now been published. The six week period during which Representations may be submitted is open from Monday 7 November 2011 until 5pm on Monday 19 December 2011. Representations received after this date will not be accepted. Should you intend to submit a Representation, whether electronically or in writing you should do so using this form (Form P3). A separate Form P3 must be completed for each issue that you wish SESplan to consider. You may raise as many issues as you wish. In line with Scottish Government advice, you are reminded that each issue must be no longer than 2,000 words whether submitted electronically or in writing. A summary of the issue that you wish SESplan to consider together with the modification / change to the Proposed Plan that is sought (to a maximum of 400 words in length) must also be provided. There is no automatic opportunity for parties to expand on their Representations later in the process. All Representations should be submitted wherever possible electronically to, [email protected] Representations may also be submitted in writing to, Proposed Plan Representations SESplan Claremont House 130 East Claremont Street Edinburgh EH7 4LB Queries should be directed to a member of the SESplan administration team on 0131 524 5164. FORM P3 – SUBMISSION OF REPRESENTATIONS FOR SESPLAN USE ONLY Reference No. PP / / Contact Name Organisation See below On Behalf Of (if Applicable) Address Telephone Email Electronic Only Yes By what means are you Hard Copy Only submitting this Issue? Both (Please tick as appropriate) Further Information Attached? Yes No No If Yes, Document Title / Ref No. -

Environmental Baseline Report 1. Introduction 1.1 This Envir

West Lothian Local Development Plan Strategic Environmental Assessment Environmental Report Appendix 1: Environmental Baseline Report 1. Introduction 1.1 This Environmental Baseline Report is to be read in tandem with the main Environmental Report. 1.2 As the Environmental Report takes a strategic and comprehensive approach, the environmental baseline for each environmental topic area is considered within a specific chapter of this separate Environmental Baseline Report. Each chapter of this report will be structured with the following sub-sections with related maps at the end of the report: a) Existing environmental issues (both strategic and other related issues); b) Existing environmental characteristics; c) Likely future changes without the implementation of the Local Plan; and d) Current environmental protection objectives and how these have been taken into account. 2. Biodiversity, Flora and Fauna 2.1 Existing Environmental Issues Strategic Environmental Issues: • Pressures from development, agricultural practices and other land uses, resulting in habitat disturbance, degradation or loss and / or species disturbance or loss. • General decline in species population distribution and numbers for a number of national, regional and / or locally important species. 1 • Spread of invasive, non-native species, particularly along water courses and riparian corridors. • Loss of or damage to sites / areas of high ecological importance. Non-statutory sites are particularly vulnerable and can be lost or damaged by operations that are out with planning control. • Fragmentation and isolation of habitats (making both the habitat areas and their dependant species populations vulnerable). • Protection and enhancement of ecosystems. Other Environmental Issues: Habitats • Although there is a wide ranging integrated habitat network (IHN) across the council area, there are some key locations where relatively small improvements could make a significant impact on the overall quality of the IHN. -

Burns Chronicle 1939

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1939 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Gatehouse-of-Fleet Burns Club The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 1891 PUBLISHED ANNUALLY SECOND SERIES : VOLUME XIV THE BURNS FEDERATION KILMARNOCK 1 939 Price Three shillings "BURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER "0 what a glorious sight, warm-reekin', rich I"-BURNS WAUGH'S SCOTCH HAGGIS Delicious-Appetising-Finely Flavoured. Made from a recipe that has no equal for Quality. A wholesome meal for the Family . On the menu of every · important Scottish function-St. Andrew's Day, Burns Anniversary, &c., &c.-at home and abroad. Per 1/4 lb. Also in hermetically sealed tins for export 1 lb. 2/· 2 lbs. 3/6 3 lbs. 5/· (plus post) AlwaJ'S book 7our orders earl7 for these dates ST. ANDREW'S DAY CHRISTMAS DAY November 30 December 25 HOGMANAY BURNS ANNIVERSARY December31 Janu&l'J' 25 Sole Molc:er Coolced In the model lcltchen1 at HaftllCOn GEORGE WAUGH 110 NICOLSON STREET, EDINBURGH, 8 SCOTLAND Telephone 42849 Telearam1 and Cables: "HAGGIS" "BURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER NATIONAL BURNS MEMORIAL COTTAGE HOME$, 1 MAUCHLINE, AYRSHIRE. i In Memory of the Poet Burns '! for Deserving Old People . .. That greatest of benevolent Institutions established In honour' .. of Robert Burns." -611,.11011 Herald. I~ I I ~ There are now twenty modern comfortable houses for the benefit of deserving old folks. The site is an ideal one in the heart of the Burns Country. -

Primary School Admission Guidance Note

PA/A2 Pupil Placement Education Services West Lothian Civic Centre Howden South Road Livingston West Lothian EH54 6FF Tel 01506 280000 Fax 01506 281869 E-mail: [email protected] Primary School Admission - Guidance Note This document contains information about primary or infant school establishments that are run by West Lothian Council. We update the information and guidance pack each year. Please complete one paper or on-line application form for each child. If you want to send your child to an independent school, you can get information from the Scottish Council of Independent Schools (SCIS). Their website is www.scis.org.uk, or phone: 0131 556 2316. If you want information on educating your child at home, please see the relevant section on the Parentzone website, at www.education.gov.scot/parentzone or phone 0131 244 4330. This document is available in Braille, Tape, Large Print and Community Languages. Please contact 01506 280000 1. Primary school contact details School Name Phone Address Website link (RC=Roman Catholic) Addiewell Primary School 01501 762794 Church Street, Addiewell, EH55 8PG https://addiewellprimary.westlothian.org.uk/ Armadale Primary School 01501 730282 Academy Street, Armadale, EH48 3JD https://armadaleprimary.westlothian.org.uk/ Balbardie Primary School 01506 652155 Torphichen Street, Bathgate, EH48 4HL https://balbardieprimary.westlothian.org.uk/ Bankton Primary School 01506 413001 Kenilworth Rise, Dedridge, Livingston, https://banktonprimary.westlothian.org.uk/ EH54 6JL Bellsquarry Primary 01506