Playing with the Player Agency Manipulation in Shadow of the Colossus and Japanese Computer Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

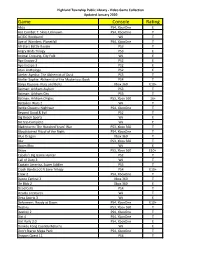

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Press Start: Video Games and Art

Press Start: Video Games and Art BY ERIN GAVIN Throughout the history of art, there have been many times when a new artistic medium has struggled to be recognized as an art form. Media such as photography, not considered an art until almost one hundred years after its creation, were eventually accepted into the art world. In the past forty years, a new medium has been introduced and is increasingly becoming more integrated into the arts. Video games, and their rapid development, provide new opportunities for artists to convey a message, immersing the player in their work. However, video games still struggle to be recognized as an art form, and there is much debate as to whether or not they should be. Before I address the influences of video games on the art world, I would like to pose one question: What is art? One definition of art is: “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.”1 If this definition were the only criteria, then video games certainly fall under the category. It is not so simple, however. In modern times, the definition has become hazy. Many of today’s popular video games are most definitely not artistic, just as not every painting in existence is considered successful. Certain games are held at a higher regard than others. There is also the problem of whom and what defines works as art. Many gamers consider certain games as works of art while the average person might not believe so. -

The Connections Between ICO and Shadow of the Colossus: a Theory by J

The Connections between ICO and Shadow of the Colossus: A Theory by J. Dean Summary Over the years, there has been an attempt by many to connect the games Ico and Shadow of the Colossus in a manner not specified by the Fumito Ueda, creator of both games (and also of the upcoming game The Last Guardian, also set in the same universe). In this brief essay, I will attempt to present my own theory concerning the connections between Ico and SotC. While I may not be the only one who presents the following theories of connection between the two games, I will say at the outset that I did not read any of these ideas off any other websites or bloggers. The theories and conclusions I will be putting forth are my own, derived solely from my knowledge, observation, and experience with both games. Any resemblance to other theories and ideas put forth by other people is purely coincidental (Warning: spoilers are included in the following essays. If you have not yet played either game but wish to continue reading, consider yourself warned...). Facts and Theories 1.) In SotC, Wander (the protagonist) brings Mono (the dead woman) to Dormin in hopes of resurrection. Wander states that she had a "cursed fate." Theory: Mono is a daughter of the Queen from Ico. Remember that the Queen needed Yorda to pass on her spirit, meaning that Yorda was intended to be nothing more than a vessel for the Queen's possession when her body became too old. It is believed that the same fate awaited Mono, as the Queen (probably in an earlier incarnation) was saving Mono for such a purpose, particularly with regard to Wander's cryptic statement about Mono's fate. -

Recommended Resources from Fortugno

How Games Tell Stories with Nick Fortugno RECOMMENDED RESOURCES FROM NICK FORTUGNO Articles & Books ● MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research ● Rules of Play Game Textbook ● Game Design Workshop Textbook ● Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience Festivals ● Come Out and Play Festival Games ● The Waiting Game at ProPublica ● Rez ● Fallout 4 ● Red Dead Redemption 2 ● Dys4ia ● The Last of Us ● Shadow of the Colossus ● Kentucky Route Zero ● Gone Home ● Amnesia ● Pandemic: Legacy ● Once Upon A Time A SELECTION OF SUNDANCE NEW FRONTIER ALUMNI / SUPPORTED PROJECTS About New Frontier: New Frontier: Storytelling at the Intersection of Art & Technology ● Walden ● 1979 Revolution ● Laura Yilmaz ● Thin Air OTHER GAMING RESOURCES ● NYU Game Center - dedicated to the exploration of games as a cultural form and game design as creative practice ● Columbia Digital Storytelling Lab - focusing on a diverse range of creative and research practices originating in fields from the arts, humanities and technology 1 OTHER GAMING RESOURCES continued ● Kotaku - gaming reviews, news, tips and more ● Steam platform indie tag - the destination for playing, discussing, and creating games ● IndieCade Festival - International festival website committed to celebrating independent interactive games and media from around the globe ● Games for Change - the leading global advocate for the games as drivers of social impact ● Immerse - digest of nonfiction storytelling in emerging media ● Emily Short's Interactive Storytelling - essays and reviews on narrative in games and new media ● The Art of Storytelling in Gaming - blog post 2 . -

2006 DICE Program

Welcome to the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences’® fifth annual D.I.C.E. Summit™. The Academy is excited to provide the forum for the interactive enter- tainment industry’s best and brightest to discuss the trends, opportunities and chal- lenges that drive this dynamic business. For 2006, we have assembled an outstanding line-up of speakers who, over the next few days, will be addressing some of the most provocative topics that will impact the creation of tomorrow’s video games. The D.I.C.E. Summit is the event where many of the industry’s leaders are able to discuss, debate and exchange ideas that will impact the video game business in the coming years. It is also a time to reflect on the industry’s most recent accomplish- ments, and we encourage every Summit attendee to join us on Thursday evening Joseph Olin, President for the ninth annual Interactive Achievement Awards®, held at The Joint at the Academy of Interactive Hard Rock Hotel. The creators of the top video games of the year will be honored Arts & Sciences for setting new standards in interactive entertainment. Thank you for attending this year’s D.I.C.E. Summit. We hope that this year’s confer- ence will provide you with ideas that spark your creative efforts throughout the year. The Academy’s Board of Directors Since its inception in 1996, the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences has relied on the leadership and direction of its board of directors. These men and women, all leaders of the interactive software industry, have volunteered their time and resources to help the Academy advance its mission of promoting awareness of the art and science of interactive games and entertainment. -

Beyond the Remake of Shadow of the Colossus a Technical Perspective

I would like to start by thanking each of you for attending this talk. There are a lot of great options and I’m flattered that you are here. I will let you know that there are bonus slides at the end of this presentation that I won’t have time to cover. However this talk and its slides will be available via the GDC Vault or feel free to reach out to me directly if you are interested. Also please don’t forget to fill out your evaluation forms, I need the feedback. So now that you are here, whether intentional or you just realized you are in the wrong room; you are most likely wondering, who the hell is this guy? Well, my name is Peter Dalton and I’m the technical director for Bluepoint Games, and as you can tell from the grey in my beard, I’ve been around for a while. I’ve been working in the games industry for over 18 years and I will never leave, I love my job, the insanely hard problems and the talented people I’m surrounded by. Over the 11+ titles that I have shipped my specialties revolve around core engine development, streaming, memory, performance, I like to believe that my job is to basically, make shit happen. So, Bluepoint Games. Perhaps you have heard of us; the Masters of the Remaster, I have to thank Digital Foundry for that title. Seriously the Digital Foundry guys are amazing. Their technical reviews are spot on and Bluepoint is tired of me ranting about how our framerate and frame pacing must be perfect or Digital Foundry will call us out. -

An Assessment of the Literary and Aesthetic Value of Japanese Video Games

WANDERING THROUGH THE VIRTUAL WORLD: AN ASSESSMENT OF THE LITERARY AND AESTHETIC VALUE OF JAPANESE VIDEO GAMES A THESIS The Faculty of the Department of Asian Studies The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Jonathan D. Curry May/2015 On my honor, I, Jonathan D. Curry, have not received unauthorized aid on this thesis. I have fully upheld the HONOR CODE of Colorado College. _______________________________________ JONATHAN D. CURRY 1 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deep gratitude for Professor Joan Ericson’s unrelenting support and insightful advice, not only during my thesis writing process but throughout my entire Colorado College career. You have helped me to achieve so many of my life goals, so I sincerely thank you. I would also like to sincerely thank Professor John Williams for his guidance in writing this thesis. You helped me find direction and purpose in my research and writing, an invaluable skill that will carry me through my future academic endeavors. I also want to give a huge thank you to my fellow Asian Studies majors. Congratulations, everyone! We made it! I know we are a small group, and we did not have many opportunities to spend time together, but I want you all to know that it has been an immense honor to work beside all of you. I would also like to acknowledge my father for his undying support for me in everything I have ever done, through thick and thin. I couldn’t have made it this far without you. -

Video Game Collection

Pokemon: Let’s Go Eevee Top-Down Turn-Based RPG | 28 hrs Pokemon: Let’s Go Pikachu Wallingford Public Library Top-Down Turn-Based RPG | 28 hrs Pokemon Shield Top-Down Turn-Based RPG | 32 hrs Animal Crossing New Horizons Coming Soon! Pokemon Sword Top-Down Turn-Based RPG | 32 hrs Captain Toad Sidescroll Platformer | 11 hrs Portal Knights Action RPG | 31 hrs Video GAme Celeste Sidescroll Platformer | 11 hrs Rime Puzzle Adventure | 9 hrs Child of Light/Valiant Hearts: Splatoon 2 Multiplayer Shooter | 12 hrs (story mode) • Child of Light Action RPG Platformer | 13 hrs Spyro Reignited Trilogy Platformer | 25 hrs • Valiant Hearts Puzzle Adventure | 7 hrs Super Mario Maker Platformer Creator | N/A Collection Civilization VI Turn-Based Strategy | 32 hrs Super Mario Odyssey Platformer | 26 hrs Crash Bandicoot N. Sane Trilogy Platformer | 20 hrs Super Mario Party Party Games | N/A Crash Team Racing Multiplayer | 8 hrs (story mode) Super Smash Bros. Ultimate Battle Royale | N/A Dark Souls Action RPG | 62 hrs Team Sonic Racing Multiplayer | 11 hrs (Story Mode) Dead Cells Sidescroll Platformer | 19 hrs Tokyo Mirage Sessions Encore Turn-Based RPG | 43 hrs Disgaea 1 Complete RPG | 56 hrs Undertale Sidescroll Turn-Based Puzzle RPG | 9 hrs Donkey Kong Tropical Freeze Platformer | 16 hrs Wandersong Musical Sidescroll Platformer | 10 hrs Dragon Quest Builders 2 Sandbox | 64 hrs The Witcher III: Wild Hunt Action RPG | 102 hrs Gone Home Narrative | 2 hrs includes Hearts of Stone 14 hours A Hat in Time Platformer | 13 hrs & Blood and Wine 31 hours Hollow Knight -

A Guide to the Videogame System

SYSTEM AND EXPERIENCE A Guide to the Videogame as a Complex System to Create an Experience for the Player A Master’s Thesis by Víctor Navarro Remesal Tutor: Asunción Huertas Roig Department of Communication Rovira i Virgili University (2009) © Víctor Navarro Remesal This Master’s Thesis was finished in September, 2009. All the graphic material belongs to its respective authors, and is shown here solely to illustrate the discourse. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my tutor for her support, advice and interest in such a new and different topic. Gonzalo Frasca and Jesper Juul kindly answered my e-mails when I first found about ludology and started considering writing this thesis: thanks a lot. I also have to thank all the good people I met at the ECREA 2008 Summer School in Tartu, for giving me helpful advices and helping me to get used to the academic world. And, above all, for being such great folks. My friends, family and specially my girlfriend (thank you, Ariadna) have suffered my constant updates on the state of this thesis and my rants about all things academic. I am sure they missed me during my months of seclusion, though, so they should be the ones I thanked the most. Thanks, mates. Last but not least, I want to thank every game creator cited directly or indirectly in this work, particularly Ron Gilbert, Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer for Monkey Island, Fumito Ueda for Ico and Shadow of the Colossus and Hideo Kojima for the Metal Gear series. I would not have written this thesis if it were not for videogames like these. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Lunch Lady and the Video Game Villain Ebook Free Download

LUNCH LADY AND THE VIDEO GAME VILLAIN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jarrett Krosoczka | 96 pages | 04 Sep 2013 | Random House USA Inc | 9780307980793 | English | New York, India Lunch Lady and the Video Game Villain PDF Book The 25 Best Horror Games. Yes, Nemesis will keep reappearing in this iteration, too, adding a serious freakout factor to the entire experience. From Oregon Trail to Overwatch, these are the games we grew up on. Kingdom Hearts: it contains multitudes! Rockstar Games. This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. The company looks at digital and retail sales to determine what games people are buying. Two all-time great villains so far, and both of them were playable characters. It's a freaking tank. A fantastic back story is the backbone of this sci-fi RPG, which casts you as a colonist who awakens from hibernation to find a strange new world before him. Collect that loot. You play as Booker DeWitt, and you're up against Zachary Comstock, the founder of the floating sky city Columbia who also happens to be an alternate universe version of Booker. And yet, many choose not to. Start your gaming journey with these titles, the 20 best video games to hit the market in the last 12 months. Ultimate is the fifth game released in the Super Smash Bros. Sony Interactive Entertainment amazon. Super Mario Maker 2. What's more, remote-operated drones are primarily what you're shooting at when you're in the tank. -

Passionate Digital Play-Based Learning: (Re)Learning in Computer Games Like Shadow of the Colossus

Passionate Digital Play-Based Learning: (Re)Learning in computer games like Shadow of the Colossus The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Mitgutsch, Konstantin. "Passionate Digital Play-Based Learning: (Re)Learning in computer games like Shadow of the Colossus." Eludamos 3 (1) (2009). As Published http://www.eludamos.org/index.php/eludamos/article/view/ vol3no1-3/102 Publisher Singapore-MIT GAMBIT Game Lab Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/100702 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. Vol. 3, No. 1 (2009) http:/www.eludamos.org Passionate Digital Play-Based Learning (Re)Learning in computer games like Shadow of the Colossus Konstantin Mitgutsch Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture. 2009; 3 (1), p. 9-22 Passionate Digital Play-Based Learning (Re)Learning in computer games like Shadow of the Colossus KONSTANTIN MITGUTSCH The power of failures and irritations for learning and experiencing is known since ancient times. Like Ulysses, the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey, the protagonist learns through experiencing obstacles and suffering through unexpected actions. In this sense the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus writes in his play "The Suppliants", how suffering is salutary: Let Him look down on mortal wantonness! (...) Urged on by passion's shunless stress. (...) And, cheated, learns too late the prey has 'scaped their hold! (...) Zeus, who leads onward mortals to be wise. -

Research/Design,” Is The

The colloquium is free and open to University of Washington Program: students, faculty, staff, and community. 8:00-9:00 AM Registration & Welcome 9:00-9:45 AM Keynote “Structured Signifiers and Infinite Games: The Keywords for Video Game Studies working group, in Serious Play @ Microsoft,” Donald Brinkman, Microsoft Research Program Manager, Games for collaboration with the Critical Gaming Project at the Learning, Digital Humanities University of Washington and the Humanities, Arts, 10:00-11:15 AM Session I “A Video Game Alternative for In-Home Thermo- Science, and Technology Advanced Collaboratory Energy Savings” by Sarah Churng, Stefani Bartz, Stephen Rice, & Nick Stoermer (HASTAC), is supported by the Simpson Center for the “Increasing Novice Learners' Engagement in an Online Programming Game” by Michael J. Lee & Humanities. For more about the Keywords group email Andrew J. Ko “Investigating Knowledge Transfer through [email protected] or go to http://bit.ly/dqlF4E Gaming: A Study of Implicit-to-Explicit Knowledge Extraction Promoted through Collaboration in Portal 2” by Michelle Zimmerman & Jeremy Stalberger The Keywords for Video Game Studies 11:15-11:30 AM Break 11:30 AM-12:30 PM Session II colloquium invites game scholars, artists, “Leet Noobs: The Life and Death of an Expert Player in World of Warcraft” by Mark Chen designers, developers, and enthusiasts to “Let’s Plays and Internet Content About Games” by Solon Scott, Michael Pfeiffer, & Vince Blas participate in roundtable discussions, 12:30-1:30 PM Lunch/Break 1:30-2:30 PM Session III presentations of individual and “Imaginary John Cage, No. 1 (for 12 Videogames)” performed by John Russell & David Baker collaborative work, scholarship, and play.