Erin Gavin Press Start: Video Games As Art Throughout the History of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating Dynamic Difficulty Adaptivity in Shoot'em up Games

SBC - Proceedings of SBGames 2013 Computing Track – Full Papers Evaluating dynamic difficulty adaptivity in shoot’em up games Bruno Baere` Pederassi Lomba de Araujo and Bruno Feijo´ VisionLab/ICAD Dept. of Informatics, PUC-Rio Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—In shoot’em up games, the player engages in a up game called Zanac [12], [13]2. More recent games that solitary assault against a large number of enemies, which calls implement some kind of difficulty adaptivity are Mario Kart for a very fast adaptation of the player to a continuous evolution 64 [40], Max Payne [20], the Left 4 Dead series [53], [54], of the enemies attack patterns. This genre of video game is and the GundeadliGne series [2]. quite appropriate for studying and evaluating dynamic difficulty adaptivity in games that can adapt themselves to the player’s skill Charles et al. [9], [10] proposed a framework for creating level while keeping him/her constantly motivated. In this paper, dynamic adaptive systems for video games including the use of we evaluate the use of dynamic adaptivity for casual and hardcore player modeling for the assessment of the system’s response. players, from the perspectives of the flow theory and the model Hunicke et al. [27], [28] proposed and tested an adaptive of core elements of the game experience. Also we present an system for FPS games where the deployment of resources, adaptive model for shoot’em up games based on player modeling and online learning, which is both simple and effective. -

Towards Balancing Fun and Exertion in Exergames

Towards Balancing Fun and Exertion in Exergames Exploring the Impact of Movement-Based Controller Devices, Exercise Concepts, Game Adaptivity and Player Modes on Player Experience and Training Intensity in Different Exergame Settings Zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigte Dissertation von Anna Lisa Martin-Niedecken (geb. Martin) aus Hadamar Tag der Einreichung: 05.11.2020, Tag der Prüfung: 11.02.2021 1. Gutachten: Prof. Dr. rer. medic. Josef Wiemeyer 2. Gutachten: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Frank Hänsel Darmstadt – D 17 Department of Human Sciences Institute of Sport Science Towards Balancing Fun and Exertion in Exergames: Exploring the Impact of Movement-Based Controller Devices, Exercise Concepts, Game Adaptivity and Player Modes on Player Experience and Training Intensity in Different Exergame Settings Zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigte Dissertation von Anna Lisa Martin-Niedecken (geb. Martin) aus Hadamar am Fachbereich Humanwissenschaften der Technischen Universität Darmstadt 1. Gutachten: Prof. Dr. rer. medic. Josef Wiemeyer 2. Gutachten: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Frank Hänsel Tag der Einreichung: 05.11.2020 Tag der Prüfung: 11.02.2021 Darmstadt, Technische Universität Darmstadt Darmstadt — D 17 Bitte zitieren Sie dieses Dokument als: URN: urn:nbn:de:tuda-tuprints-141864 URL: https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/id/eprint/14186 Dieses Dokument wird bereitgestellt von tuprints, E-Publishing-Service der TU Darmstadt http://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de [email protected] Jahr der Veröffentlichung der Dissertation auf TUprints: 2021 Die Veröffentlichung steht unter folgender Creative Commons Lizenz: Namensnennung – Share Alike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) Attribution – Share Alike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Erklärungen laut Promotionsordnung §8 Abs. -

Videogames in the Museum: Participation, Possibility and Play in Curating Meaningful Visitor Experiences

Videogames in the museum: participation, possibility and play in curating meaningful visitor experiences Gregor White Lynn Parker This paper was presented at AAH 2016 - 42nd Annual Conference & Book fair, University of Edinburgh, 7-9 April 2016 White, G. & Love, L. (2016) ‘Videogames in the museum: participation, possibility and play in curating meaningful visitor experiences’, Paper presented at Association of Art Historians 2016 Annual Conference and Bookfair, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 7-9 April 2016. Videogames in the Museum: Participation, possibility and play in curating meaningful visitor experiences. Professor Gregor White Head of School of Arts, Media and Computer Games, Abertay University, Dundee, UK Email: [email protected] Lynn Parker Programme Leader, Computer Arts, Abertay University, Dundee, UK Email: [email protected] Keywords Videogames, games design, curators, museums, exhibition, agency, participation, rules, play, possibility space, co-creation, meaning-making Abstract In 2014 Videogames in the Museum [1] engaged with creative practitioners, games designers, curators and museums professionals to debate and explore the challenges of collecting and exhibiting videogames and games design. Discussions around authorship in games and games development, the transformative effect of the gallery on the cultural reception and significance of videogames led to the exploration of participatory modes and playful experiences that might more effectively expose the designer’s intent and enhance the nature of our experience as visitors and players. In proposing a participatory mode for the exhibition of videogames this article suggests an approach to exhibition and event design that attempts to resolve tensions between traditions of passive consumption of curated collections and active participation in meaning making using theoretical models from games analysis and criticism and the conceit of game and museum spaces as analogous rules based environments. -

Art Styles in Computer Games and the Default Bias

University of Huddersfield Repository Jarvis, Nathan Photorealism versus Non-Photorealism: Art styles in computer games and the default bias. Original Citation Jarvis, Nathan (2013) Photorealism versus Non-Photorealism: Art styles in computer games and the default bias. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/19756/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ THE UNIVERSITY OF HUDDERSFIELD Photorealism versus Non-Photorealism: Art styles in computer games and the default bias. Master of Research (MRes) Thesis Nathan Jarvis - U0859020010 18/09/2013 Supervisor: Daryl Marples Co-Supervisor: Duke Gledhill 1.0.0 – Contents. 1.0.0 – CONTENTS. 1 2.0.0 – ABSTRACT. 4 2.1.0 – LITERATURE REVIEW. 4 2.2.0 – SUMMARY OF CHANGES (SEPTEMBER 2013). -

Indoor Fireworks: the Pleasures of Digital Game Pyrotechnics

Indoor Fireworks: the Pleasures of Digital Game Pyrotechnics Simon Niedenthal Malmö University, School of Arts and Communication Malmö, Sweden [email protected] Abstract: Fireworks in games translate the sensory power of a real-world aesthetic form to the realm of digital simulation and gameplay. Understanding the role of fireworks in games can best be pursued through through a threefold aesthetic perspective that focuses on the senses, on art, and on the aesthetic experience that gives pleasure through the player’s participation in the simulation, gameplay and narrative potentials of fireworks. In games ranging from Wii Sports and Fantavision, to Okami and Assassin’s Creed II, digital fireworks are employed as a light effect, and are also the site for gameplay pleasures that include design and performance, timing and rhythm, and power and awe. Fireworks also gain narrative significance in game forms through association with specific sequences and characters. Ultimately, understanding the role of fireworks in games provokes us to reverse the scrutiny, and to consider games as fireworks, through which we experience ludic festivity and voluptuous panic. Keywords: Fireworks, Pyrotechnics, Digital Games, Game Aesthetics 1. Introduction: On March 9th, 2000, Sony released the fireworks-themed Fantavision (Sony Computer Entertainment 2000) in Japan as one of the very first titles for its then new Playstation 2. Fantavision exhibits many of the desirable qualities for good launch title: simulation properties that show off new graphic capabilities, established gameplay that is quick to grasp, a broad appeal. Though the critical reception for the game was ultimately lukewarm (a 72 rating from Metacritic.com), it is notable that Sony launched its new console with a fireworks game. -

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

Effects of Art Styles on Video Game Narratives

Effects of Art Styles on Video Game Narratives UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Department of Future Technologies Master's Thesis July 2018 Leena Hölttä UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Department of Future Technologies HÖLTTÄ, LEENA Effects of Art Styles on Video Game Narratives Master's thesis, 76 pages, 29 appendix pages Computer Science August 2018 The effect of an art style on a video game's narrative is not widely studied and not much is known about how the general player base views the topic. This thesis attempts to answer this question through the use of two different surveys, a general theory related one, and one based upon images and categorization and a visual novel based interview that aims at gaining a further understanding of the subject. The general results point to the art style creating and emphasizing a narrative's mood and greatly enhancing the player experience. Based on these results a simple framework ASGDF was created to help beginning art directors and designers to create the most fitting style for their narrative. Key words: video games, art style, art, narrative, games TURUN YLIOPISTO Tulevaisuuden teknologioiden laitos HÖLTTÄ, LEENA Taidetyylien vaikutus videopelien narratiiviin Pro gradu -tutkielma, 76 s., 29 liites. Tietojenkäsittelytiede Elokuu 2018 Taidetyylien vaikutus videopelien narratiiviin ei ole laajasti tutkittu aihe, eikä ole laajasti tiedossa miten yleinen pelaajakunta näkee aiheen. Tämä tutkielma pyrkii vastaamaan tähän kysymykseen kahden eri kyselyn avulla, joista toinen on teoriaan perustuva kysely, ja toinen kuvien kategorisointiin perustuva kysely. Myös visuaalinovelliin perustuvaa haastattelua käytettiin tutkimuskysymyksen tutkimiseen. Yleiset tulokset viittaavat siihen, että taidetyyli vaikuttaa narratiivin tunnelmaan ja korostaa pelaajan kokemusta. -

The Decline of Mmos

The Decline of MMOs Prof. Richard A. Bartle University of Essex United Kingdom May 2013 Abstract Ten years ago, massively-multiplayer online role-playing games (MMOs) had a bright and exciting future. Today, their prospects do not look so glorious. In an effort to attract ever-more players, their gameplay has gradually been diluted and their core audience has deserted them. Now that even their sources of new casual players are drying up, MMOs face a slow and steady decline. Their problems are easy to enumerate: they cost too much to make; too many of them play the exact same way; new revenue models put off key groups of players; they lack immersion; they lack wit and personality; players have been trained to want experiences that they don’t actually want; designers are forbidden from experimenting. The solutions to these problems are less easy to state. Can anything be done to prevent MMOs from fading away? Well, yes it can. The question is, will the patient take the medicine? Introduction From their lofty position as representing the future of videogames, MMOs have fallen hard. Whereas once they were innovative and compelling, now they are repetitive and take-it-or-leave-it. Although they remain profitable at the moment, we know (from the way that the casual games market fragmented when it matured) that this is not sustainable in the long term: players will either leave for other types of game or focus on particular mechanics that have limited appeal or that can be abstracted out as stand-alone games (or even apps). -

Journal of Games Is Here to Ask Himself, "What Design-Focused Pre- Hideo Kojima Need an Editor?" Inferiors

WE’RE PROB NVENING ABLY ALL A G AND CO BOUT V ONFERRIN IDEO GA BOUT C MES ALSO A JournalThe IDLE THUMBS of Games Ultraboost Ad Est’d. 2004 TOUCHING THE INDUSTRY IN A PROVOCATIVE PLACE FUN FACTOR Sessions of Interest Former developers Game Developers Confer We read the program. sue 3D Realms Did you? Probably not. Read this instead. Computer game entreprenuers claim by Steve Gaynor and Chris Remo Duke Nukem copyright Countdown to Tears (A history of tears?) infringement Evolving Game Design: Today and Tomorrow, Eastern and Western Game Design by Chris Remo Two founders of long-defunct Goichi Suda a.k.a. SUDA51 Fumito Ueda British computer game developer Notable Industry Figure Skewered in Print Crumpetsoft Disk Systems have Emil Pagliarulo Mark MacDonald sued 3D Realms, claiming the lat- ter's hit game series Duke Nukem Wednesday, 10:30am - 11:30am infringes copyright of Crumpetsoft's Room 132, North Hall vintage game character, The Duke of industry session deemed completely unnewswor- Newcolmbe. Overview: What are the most impor- The character's first adventure, tant recent trends in modern game Yuan-Hao Chiang The Duke of Newcolmbe Finds Himself design? Where are games headed in the thy, insightful next few years? Drawing on their own in a Bit of a Spot, was the Walton-on- experiences as leading names in game the-Naze-based studio's thirty-sev- design, the panel will discuss their an- enth game title. Released in 1986 for swers to these questions, and how they the Amstrad CPC 6128, it features see them affecting the industry both in Japan and the West. -

Estudios Sega Europe

ESTUDIOS SEGA EUROPE UNITED GAME ARTISTS Ya sea con carreras de rallies o con ritmos de rock, United Game Artists (antes AM9) toca todos los terrenos. Desde sus orígenes como uno de los mejores equipos de Sega en el campo de los juegos de carreras (con títulos como Sega Rally Championship) hasta su nuevo interés por marchosos juegos musicales (con, por ejemplo, Space Channel 5), UGA ha demostrado que nadie les supera a la hora de hacer las cosas con estilo. AM9 se transformó en United Game Artists el 27 de abril de 2000 y su sede, que da cabida a 55 empleados presididos por Tetsuya Mizuguchi, se encuentra en el moderno distrito de Shibuya, en Tokio. Mizuguchi nació en Sapporo y asistió a la Facultad de Bellas de Artes de la Nihon University, para luego entrar en Sega en 1990. Su primer trabajo fue Megalopolice, película japonesa de carreras con gráficos creados por ordenador. A continuación, puso sus miras en los simuladores deportivos y en 1995 creó una obra maestra de las salas recreativas, Sega Rally Championship. Simulando el siempre resbaladizo y todoterreno mundo del rally, el juego de Sega destacó por un estilo de conducción del todo innovador para cualquier aficionado a los arcades. Entre las características de Sega Rally estaba la posibilidad de escoger 2 coches y competir en 3 pistas distintas, unos gráficos sorprendentes gracias a la placa Model 2, un sencillo sistema de control y un modo de competición. Además, se creó incluso una versión de la máquina que traía una réplica de un coche con sistema hidráulico.. -

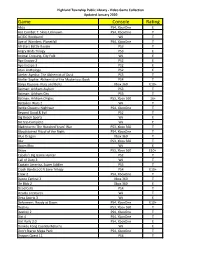

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Becoming Human? Ableism and Control in <Em>Detroit: Become

Human-Machine Communication Volume 2, 2021 https://doi.org/10.30658/hmc.2.7 Becoming Human? Ableism and Control in Detroit: Become Human and the Implications for Human- Machine Communication Marco Dehnert1 and Rebecca B. Leach1 1 The Hugh Downs School of Human Communication, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA Abstract In human-machine communication (HMC), machines are communicative subjects in the creation of meaning. The Computers are Social Actors and constructivist approaches to HMC postulate that humans communicate with machines as if they were people. From this perspective, communication is understood as heavily scripted where humans mind- lessly apply human-to-human scripts in HMC. We argue that a critical approach to com- munication scripts reveals how humans may rely on ableism as a means of sense-making in their relationships with machines. Using the choose-your-own-adventure game Detroit: Become Human as a case study, we demonstrate (a) how ableist communication scripts ren- der machines as both less-than-human and superhuman and (b) how such scripts manifest in control and cyborg anxiety. We conclude with theoretical and design implications for rescripting ableist communication scripts. Keywords: human-machine communication, ableism, control, cyborg anxiety, Computers are Social Actors (CASA) Introduction Human-Machine Communication (HMC) refers to both a new area of research and concept within communication, defined as “the creation of meaning among humans and machines” (Guzman, 2018, p. 1; Fortunati & Edwards, 2020). HMC invites a shift in perspective where CONTACT Marco Dehnert • The Hugh Downs School of Human Communication • Arizona State University • P.O. Box 871205 • Tempe, AZ 85287-1205, USA • [email protected] ISSN 2638-602X (print)/ISSN 2638-6038 (online) www.hmcjournal.com Copyright 2021 Authors.