Videogames in the Museum: Participation, Possibility and Play in Curating Meaningful Visitor Experiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

Effects of Art Styles on Video Game Narratives

Effects of Art Styles on Video Game Narratives UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Department of Future Technologies Master's Thesis July 2018 Leena Hölttä UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Department of Future Technologies HÖLTTÄ, LEENA Effects of Art Styles on Video Game Narratives Master's thesis, 76 pages, 29 appendix pages Computer Science August 2018 The effect of an art style on a video game's narrative is not widely studied and not much is known about how the general player base views the topic. This thesis attempts to answer this question through the use of two different surveys, a general theory related one, and one based upon images and categorization and a visual novel based interview that aims at gaining a further understanding of the subject. The general results point to the art style creating and emphasizing a narrative's mood and greatly enhancing the player experience. Based on these results a simple framework ASGDF was created to help beginning art directors and designers to create the most fitting style for their narrative. Key words: video games, art style, art, narrative, games TURUN YLIOPISTO Tulevaisuuden teknologioiden laitos HÖLTTÄ, LEENA Taidetyylien vaikutus videopelien narratiiviin Pro gradu -tutkielma, 76 s., 29 liites. Tietojenkäsittelytiede Elokuu 2018 Taidetyylien vaikutus videopelien narratiiviin ei ole laajasti tutkittu aihe, eikä ole laajasti tiedossa miten yleinen pelaajakunta näkee aiheen. Tämä tutkielma pyrkii vastaamaan tähän kysymykseen kahden eri kyselyn avulla, joista toinen on teoriaan perustuva kysely, ja toinen kuvien kategorisointiin perustuva kysely. Myös visuaalinovelliin perustuvaa haastattelua käytettiin tutkimuskysymyksen tutkimiseen. Yleiset tulokset viittaavat siihen, että taidetyyli vaikuttaa narratiivin tunnelmaan ja korostaa pelaajan kokemusta. -

Heroes of Warland in Madrid World Football Summit

PRESS RELEASE 24 September 2018 at 09:00 (EEST) Heroes of Warland in Madrid World Football Summit Nitro Games presents its upcoming game Heroes of Warland in World Football Summit this week in Madrid, Spain. “We consider Spain a very important market in the field of eSports. In WFS we’re presenting Heroes of Warland for Spanish speaking audience, as well as exploring opportunities related to competitive gaming and eSports on mobile.” says Jussi Tähtinen, CEO & Co-Founder, Nitro Games Oyj. The World Football Summit takes place in Teatro Goya, Madrid on September 24 – 25. WFS is the international event of the football industry, gathering 2300+ attendees and the most influential professionals from 80+ countries, as well as 160+ clubs and 100+ medias, in order to discuss the most relevant topics and to generate business opportunities. Several of these parties are also active in the field of eSports. Nitro Games is attending the event to showcase Heroes of Warland and Heroes & Superstars reality show. CEO Jussi Tähtinen is also a speaker at the event. Find out more about WFS: https://worldfootballsummit.com/en/ Heroes of Warland is now available in Google Play Open Beta in 139 countries. This means the game is available globally for early testers having Android devices, excluding China and few other countries. The game is featured in Google Play in Early Access category in all 139 countries. Heroes of Warland is a team-based competitive multiplayer game on mobile. With Heroes of Warland, Nitro Games is introducing hero-based shooter genre on mobile for the first time. -

Art Games Applied to Disability

Figure 1. Thatgamecompany. PlayStation 3. (2009), Flower. Figure 2. Thatgamecompany. PlayStation 4. (2013), Flow. Esther Guanche Dorta. Phd student. [email protected] Ana Marqués Ibáñez. Teacher. [email protected] Department of Didactics of Plastic Expression. Faculty of Education. University of La Laguna. Tenerife. Art Games applied to disability. Figure 3. Thatgamecompany. PlayStation 3. (2012), Journey. THEME 4 – Technology – S3 DT Art Games, Disabilities, Design, Videogames, Inclusive education. Art Games applied to disability. Videogames are an emerging medium which represent a new form of artistic design, creating another means of expression for artists as well as different educational context adapted to people with dissabilities. Abstract This is a study of several examples of artistic videogames which can be 1. Art Games and Indie Games Concept The MOMA2 arranged an exhibition on the 50 years of videogame history, made a used to improve the quality of life of persons with impairment, for those review about the design and has added the most significant games to its permanent with specific or general motoric disabilities and mental disabilities in Art Game is an art object associated to the new interactive communications media exhibition, such as those of the Johnson Gallery with 14 videogames, which have order to bring them closer to art and design studies. As well as to develop new approaches in order to include this medium in artistic and a subgenre of the so-called serious videogames. The term was first used in been increased to around fifty. productions, study the impact of these images in Visual Culture and its academic circles in 2002, and referred to a videogame designed to boost artistic and construction by designing. -

The Art of Video Games @ Smithsonian

This page was exported from - Digital meets Culture Export date: Tue Sep 28 13:43:42 2021 / +0000 GMT The Art of Video Games @ Smithsonian The Smithsonian American Art Museum hosts a very special exhibition, to explore the forty-year evolution of video games as an artistic medium, with a focus on striking visual effects and the creative use of new technologies. An amalgam of traditional art forms ? painting, writing, sculpture, music, storytelling, cinematography ? video games are an increasingly expressive medium and offer artists a previously unprecedented method of communicating with and engaging audiences: in the forty years since the introduction of the first home video game, the field has attracted exceptional artistic talent. The exhibition features some of the most influential artists and designers during five eras of game technology, from early pioneers to contemporary designers, and is focused on the interplay of graphics, technology and storytelling through some of the best games for twenty gaming systems ranging from the Atari VCS to the PlayStation 3. Eighty games, selected with a poll by the public that replied enthusiastically - more than 3.7 million votes were cast by 119,000 people in 175 countries! - to the Smithsonian's call, demonstrate the evolution of the medium. The games are presented through still images and video footage. Five featured games, one from each era, show how players interact with diverse virtual worlds, highlighting innovative techniques that set the standard for many subsequent games. The playable games are Pac-Man, Super Mario Brothers, The Secret of Monkey Island, Myst, and Flower. Further the exhibition, there are video interviews with twenty developers and artists, large prints of in-game screen shots, and historic game consoles. -

The Dreamcast, Console of the Avant-Garde

Loading… The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association Vol 6(9): 82-99 http://loading.gamestudies.ca The Dreamcast, Console of the Avant-Garde Nick Montfort Mia Consalvo Massachusetts Institute of Technology Concordia University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract We argue that the Dreamcast hosted a remarkable amount of videogame development that went beyond the odd and unusual and is interesting when considered as avant-garde. After characterizing the avant-garde, we investigate reasons that Sega's position within the industry and their policies may have facilitated development that expressed itself in this way and was received by gamers using terms that are associated with avant-garde work. We describe five Dreamcast games (Jet Grind Radio, Space Channel 5, Rez, Seaman, and SGGG) and explain how the advances made by these industrially productions are related to the 20th century avant- garde's lesser advances in the arts. We conclude by considering the contributions to gaming that were made on the Dreamcast and the areas of inquiry that remain to be explored by console videogame developers today. Author Keywords Aesthetics; art; avant-garde; commerce; console games; Dreamcast; game studios; platforms; politics; Sega; Tetsuya Mizuguchi Introduction A platform can facilitate new types of videogame development and can expand the concept of videogaming. The Dreamcast, however brief its commercial life, was a platform that allowed for such work to happen and that accomplished this. It is not just that there were a large number of weird or unusual games developed during the short commercial life of this platform. We argue, rather, that avant-garde videogame development happened on the Dreamcast, even though this development occurred in industrial rather than "indie" or art contexts. -

The Art of Play: Video Games Exhibit Opens at Museum in Washington

29 March 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com The Art of Play: Video Games Exhibit Opens at Museum in Washington VOA The new exhibit at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American Art JUNE SIMMS: Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English. (MUSIC) I'm June Simms. On the program today, we play new music from Justin Townes Earle … And we return to a story about the sale of shares in a company that operates a famous New York skyscraper … But first, we go play games at an art show in Washington. (MUSIC) "The Art of Video Games" JUNE SIMMS: Most art exhibits have a no-touch policy. At the Smithsonian Institution, guards often give a warning if people position themselves too close to works of art. But, right now, the Smithsonian's National Museum of American Art 2 is inviting visitors to play with parts of its new exhibit, "The Art of Video Games." Mario Ritter has our story. MARIO RITTER: Six-year-old gamer Jacob Smith enjoys playing at the museum. JACOB SMITH: "Awesome." Jacob was prepared to take a favorite video game he found there. JACOB SMITH: "I was really excited. I think that you could buy games here. Like I have some money." But none of the eighty games are for sale. They all are on loan from Chris Melissinos, who set up the show. CHRIS MELISSINOS: "Video games have been present in my life since as long as I can remember." Chris Melissinos sees video games as more than just play things. He suspects other people feel the same way. -

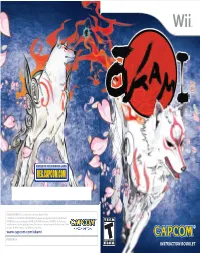

Instruction Booklet

CAPCOM ENTERTAINMENT, INC., 800 Concar Drive, Suite 300, San Mateo, CA 94402 © CAPCOM CO., LTD. 2006, 2008 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Wii development by Ready At Dawn Studios LLC. CAPCOM and the CAPCOM LOGO are registered trademarks of CAPCOM CO., LTD. ŌKAMI is a trademark of CAPCOM CO., LTD. The typefaces included herein are solely developed by DynaComware. The rating icon is a registered trademark of the Entertainment Software Association. All other trademarks are owned by their respective owners. www.capcom.com/okami PRINTED IN USA INSTRUCTION BOOKLET ESRB on Front: 14 x 21 mm OKAMI: Wii Manual Cover - Round 5 Prepared by Eclipse Advertising on: February 28, 2008 PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE Wii™ OPERATIONS MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE USING YOUR Wii HARDWARE SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS MANUAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT The Official Seal is your assurance that this product is licensed or manufactured by HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. Nintendo. Always look for this seal when buying video game systems, accessories, games and related products. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES. Dolby, Pro Logic, and the double-D symbol are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. Manufactured under license from Dolby Laboratories. WARNING – Seizures This game is presented in Dolby Pro Logic II. To play games that carry the Dolby Pro Logic II logo in surround sound, you will need a Dolby Pro Logic II, Dolby Pro Logic or Dolby Pro Logic IIx receiver. These • Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by light flashes or receivers are sold separately. -

The Introduction of Computer and Video Games in Museums – Experiences and Possibilities

The Introduction of Computer and Video Games in Museums – Experiences and Possibilities Tiia Naskali, Jaakko Suominen, and Petri Saarikoski University of Turku, Digital Culture, Degree Program of Cultural Production and Landscape Studies, Pori, Finland {tiia.naskali,jaakko.suominen,petri.saarikoski}@utu.fi Abstract. Computers and other digital devices have been used for gaming since the 1940s. However, the growth in popularity of commercial videogames has only recently been witnessed in museums. This paper creates an overview of how digital gaming devices have been introduced in museum exhibitions over the last fifteen years. The following discussion will give examples of exhibitions from different countries and provide answers to the following questions: Can digital games and gaming devices be used as promotional gimmicks for attracting new audiences to museums? How can mainframe computers be taken into account in digital game related exhibitions? How has the difference between cultural-historical and art museum contexts affected the methods for introducing digital games? Is there still room for general exhibitions of digital games or should one focus more on special theme exhibitions? How are museum professionals, researchers and computer hobbyists able to collaborate in exhibition projects? Keywords: Digital games, museums, exhibitions. 1 Introduction – Pulling in with Digital Games The popularity of digital games has increased during the last few decades. The playing of games plays an important role in many people’s lives, and the average age of players is, in many countries, almost 40 years-old. In Finland, for example, the average age of the digital game player was 37 years-old in 2011, while a total of 73 % of Finns played digital games. -

Press Start: Video Games and Art

Press Start: Video Games and Art BY ERIN GAVIN Throughout the history of art, there have been many times when a new artistic medium has struggled to be recognized as an art form. Media such as photography, not considered an art until almost one hundred years after its creation, were eventually accepted into the art world. In the past forty years, a new medium has been introduced and is increasingly becoming more integrated into the arts. Video games, and their rapid development, provide new opportunities for artists to convey a message, immersing the player in their work. However, video games still struggle to be recognized as an art form, and there is much debate as to whether or not they should be. Before I address the influences of video games on the art world, I would like to pose one question: What is art? One definition of art is: “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.”1 If this definition were the only criteria, then video games certainly fall under the category. It is not so simple, however. In modern times, the definition has become hazy. Many of today’s popular video games are most definitely not artistic, just as not every painting in existence is considered successful. Certain games are held at a higher regard than others. There is also the problem of whom and what defines works as art. Many gamers consider certain games as works of art while the average person might not believe so. -

The Intentions of International Tourists to Attend the 2016 Rio Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games: a Study of the Image of Rio De Janeiro and Brazil

Ann Appl Sport Sci 8(3): e798, 2020. http://www.aassjournal.com; e-ISSN: 2322–4479; p-ISSN: 2476–4981. 10.29252/aassjournal.798 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The Intentions of International Tourists to Attend the 2016 Rio Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games: A Study of the Image of Rio de Janeiro and Brazil Leonardo Jose Mataruna-Dos-Santos* College of Business Administration, American University in the Emirates, Dubai, UAE. Submitted 22 September 2019; Accepted in final form 27 February 2020. ABSTRACT Background. This paper investigates how hosting a mega sports event such as the 2016 Rio Games – Olympic and Paralympic influence the Rio de Janeiro and Brazil image’ like popular destinations among tourists. Objectives. The following hypotheses guided our research to identify the more positive image of Brazil as a tourism destination. Methods. A mixed research design combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches was used. Participants were recruited at the Technische Universität München and in the city center of Munich, Germany. The two dimensions (cognitive and affective) of the tourism destination image were considered to elaborate a questionnaire survey, which mixes both qualitative and quantitative methods. Results. The significant factors influencing the intentions of a person to attend the Games in Brazil are the positive portrayed image of the country and their sport interest. According to the multiple regression conducted, the only variables, which have influenced people’s intention to go to Brazil for the Olympics, were the image of the country as a tourism destination (β = 0.404, p < 0.05) and sports interests (β = 0.259, p < 0.05). -

From Regional Sports Rivalry to Separatist Politics

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-5-2015 More Than Just A Game: From Regional Sports Rivalry to Separatist Politics Ruitong Zhou Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons Recommended Citation Zhou, Ruitong, "More Than Just A Game: From Regional Sports Rivalry to Separatist Politics" (2015). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 901. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/901 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. More Than Just A Game: From Regional Sports Rivalry to Separatist Politics A Capstone Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Ruitong Zhou Candidate for Bachelor of Arts Degree and Renée Crown University Honors May 2015 Honors Capstone Project in: Public Relations, International Relations, and Political Science Capstone Project Advisor: _______________________ Professor Joan Deppa Capstone Project Reader: _______________________ Professor Dieter Roberto Kuehl Honors Director: _______________________ Stephen Kuusisto, Director Date: [April 20, 2015] i Abstract In the Capstone, I will explore one of the most intense football clashes in history: El Clásico (The Classic), which refers to a match-up between Real Madrid C.F. and FC Barcelona. When these most successful football clubs meet on the field for 90 minutes of intense action, it soon becomes very clear that this is much more than just a game or just sports.