Reshoring and Its Impact on Transportation Infrastructure & US Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automotive – Winter 2019 Industry Insights: Automotive – Winter 2019

INDUSTRY INSIGHTS Automotive – Winter 2019 Industry Insights: Automotive – Winter 2019 2 0 1 8 B Y Highlights THE NUMBERS The automotive industry slowed in the second half of 2018 as global sales, earnings and stock prices stalled due primarily to economic uncertainty and declining consumer confidence globally after a strong opening half to the year. The automotive industry continues to evolve as Global light vehicle sales decreased by 0.5% 1 electrification gains a stronger foothold globally and autonomous vehicle in 2018 compared to 2017. development remains a focus. Late in the year, North American automakers implemented drastic restructuring plans to eliminate less profitable sedans from their lineups and focus on larger vehicles. For the year, China’s auto sales fell 1.7% with Global light vehicle sales declined 0.5% in 2018 relative to 2017 driven 1,4 by the unexpected decline in China. In the U.S., light vehicle sales grew 27.7 million units sold. 0.6% in 2018 to 17.3 million units.1 In December 2018, U.S. light vehicle sales reached 17.51 million units at a seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR), in line with recent historical periods.2 In 2018, U.S. light vehicle SAAR was 17.29 Interest rates on consumer installment loans for new automobiles million units, up from the 17.19 million mark in reached 5.30% in November 2018 in the U.S., up from 4.81% in 2017.2 November 2017 and the 5.05% mark in August 2018, creating further headwinds for the industry.3 In 2018, auto production and sales in China declined 4.29% and 2.8%, New passenger registrations increased by respectively, compared to 2017. -

Chapter 11 ) FISKER AUTOMOTIVE HOLDINGS, INC., Et Al.,1 ) Case No

Case 13-13087-KG Doc 157 Filed 12/13/13 Page 1 of 11 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) FISKER AUTOMOTIVE HOLDINGS, INC., et al.,1 ) Case No. 13-13087 (KG) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) MOTION OF THE DEBTORS FOR ENTRY OF AN ORDER (A) AUTHORIZING THE EMPLOYMENT AND RETENTION OF BEILINSON ADVISORY GROUP, LLC AS RESTRUCTURING ADVISORS FOR THE DEBTORS, EFFECTIVE NUNC PRO TUNC TO THE PETITION DATE AND (B) WAIVING CERTAIN TIME-KEEPING REQUIREMENTS PURSUANT TO LOCAL RULE 2016-2(H) The above-captioned debtors (collectively, the “Debtors”) file this motion (the “Motion”) for entry of an order, substantially in the form attached hereto as Exhibit A (the “Order”): (a) authorizing the Debtors’ employment and retention of Beilinson Advisory Group, LLC and its subsidiaries, affiliates, agents, and independent contractors (collectively, “BAG”), as their restructuring advisors in connection with these chapter 11 cases effective nunc pro tunc to the Petition Date (as defined below), including the engagement of Marc Beilinson as Chief Restructuring Officer; and (b) waiving certain time-keeping requirements pursuant to Local Rule 2016-2(h). In support of this Motion, the Debtors submit the Declaration of Marc Beilinson, the Debtors’ Chief Restructuring Officer (the “Beilinson Declaration”), attached hereto as Exhibit B. In further support of this Motion, the Debtors respectfully state as follows: 1 The Debtors, together with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Fisker Automotive Holdings, Inc. (9678); and Fisker Automotive, Inc. (9075). For the purpose of these chapter 11 cases, the service address for the Debtors is: 5515 E. -

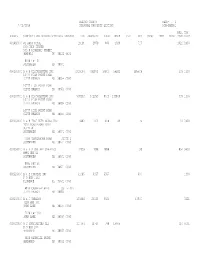

1 7/01/2014 Personal Property Listing Pgm-Paedrl Bus

DESOTO COUNTY PAGE- 1 7/01/2014 PERSONAL PROPERTY LISTING PGM-PAEDRL BUS. TAX ______PARCEL _____________________________________NAME/MAILING ADDRESS/PHYSICAL ADDRESS ____TRUE ________ASSESSED ____FURN ____MECH ____LESD ____INVT ____BANK ____DEBT ____MISC ____TYPE ____DIST 001692000 #1 AUTO STORE 19191 2879 833 1329 717 1022 2400 C/O JOHN TURNER 503 N HIGHLAND STREET MEMPHIS TN 38122 4521 8108 HWY 51 SOUTHAVEN MS 38671 000103000 A & B DISTRIBUTING INC 3219144 482872 37843 59521 385508 339 1300 10777 HIGH POINT ROAD OLIVE BRANCH MS 38654 0000 10777 HIGH POINT ROAD OLIVE BRANCH MS 38654 0000 000103001 A & B DISTRIBUTING INC 948352 142253 8445 133808 339 1306 10777 HIGH POINT ROAD OLIVE BRANCH MS 38654 0000 10777 HIGH POINT ROAD OLIVE BRANCH MS 38654 0000 002663000 A & B FAST AUTO GLASS INC 6682 1002 878 49 75 31 2400 7020 TCHULAHOMA ROAD SUITE #1 SOUTHAVEN MS 38671 0000 7020 TCHULAHOMA ROAD SUITE 1 SOUTHAVEN MS 38671 0000 003356000 A & B SIGNS AND GRAPHICS 12639 1896 1858 38 854 3400 8985 HWY 51 SOUTHAVEN MS 38671 0000 8985 HWY 51 SOUTHAVEN MS 38671 0000 002526000 A & E HOSPICE INC 41045 6157 5557 600 1300 P O BOX 1332 FLORENCE AL 35631 0000 6810 CRUMPLER BLVD SUITE 101 OLIVE BRANCH MS 38654 002132000 A & J TOBACCO 133464 20020 6520 13500 3221 7128 HWY 301 HORN LAKE MS 38637 0000 7128 HWY 301 HORN LAKE MS 38637 0000 002722000 A C SPECIALTIES LLC 111754 16763 798 15965 314 5101 P O BOX 277 HERNANDO MS 38632 0000 3425 MAGNOLIA DRIVE HERNANDO MS 38632 0000 DESOTO COUNTY PAGE- 2 7/01/2014 PERSONAL PROPERTY LISTING PGM-PAEDRL BUS. -

Countervailing Duty Administrative (NAICS 621) About Telemedicine Solar Cells from China

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 237 / Wednesday, December 9, 2020 / Notices 79163 service delivery for the healthcare DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE days.2 On July 21, 2020, Commerce industry, and its importance has tolled the due date for these final results increased during the current pandemic. International Trade Administration an additional 60 days.3 On September 25, 2020, Commerce extended the Expanding the collection of data on [C–570–980] telemedicine use will support deadline for issuing the final results of measurement on changes in its adoption Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Cells, this review by 60 days, until November 4 during this unprecedented public health Whether or Not Assembled Into 27, 2020. emergency. SAS currently asks Modules, From the People’s Republic Scope of the Order of China: Final Results of ambulatory health care providers The products covered by the order are Countervailing Duty Administrative (NAICS 621) about telemedicine solar cells from China. A full Review; 2017 services in relation to patient visits. description of the scope of the order is This proposal will add a question about AGENCY: Enforcement and Compliance, contained in the Issues and Decision revenues from telemedicine services for International Trade Administration, Memorandum.5 hospitals (NAICS 622) and nursing Department of Commerce. homes (NAICS 623). Furthermore, to Analysis of Comments Received SUMMARY: The Department of Commerce standardize content across industries All issues raised in interested parties’ (Commerce) determines that and provide consistency for briefs are addressed in the Issues and countervailable subsidies are being respondents, the current telemedicine Decision Memorandum accompanying provided to producers/exporters of this notice. -

Final Survey Report DME Utilisation Sept 2

TIFAC, DST, GOVT. OF INDIA | SURVEY ON UTILIZATION ISSUES OF METHANOL & DME CONTENTS S.NO DESCRIPTION PAGE Executive Summary 1.0 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1.1 India Energy Outlook 1.1 1.2 India Chemicals Sector 1.3 1.3 India Resource Status 1.3 1.3.1 Crude Oil 1.4 1.3.2 Coal 1.6 1.3.2.1 Coal Reserves 1.6 1.3.2.2 Coal Production 1.6 1.3.3 LPG 1.7 1.3.4 Petrol(Motor Spirit/Gasoline) 1.8 1.3.5 Natural Gas 1.8 1.3.6 Coal Bed Methane 1.10 1.3.7 Gas Hydrate 1.10 1.3.8 Biomass 1.12 1.4 Report Structure 1.13 2.0 CHAPTER-2: STATUS OF METHANOL INDUSTRIES 2.1 2.1 Introduction 2.1 2.1.1 Product Pathways 2.1 2.1.2 Properties 2.2 2.2 Methanol National Status 2.2 2.2.1 Manufacturers of Methanol 2.3 2.2.1.1 GNFC, Bharuch (Gujarat) 2.3 2.2.1.2 Deepak Fertilizers & Petrochemicals, Raigarh 2.4 2.2.1.3 RCF, Mumbai 2.4 2.2.1.4 NFL, Nangal (Punjab) 2.5 2.2.1.5 Assam Petrochemicals Limited 2.5 1 TIFAC, DST, GOVT. OF INDIA | SURVEY ON UTILIZATION ISSUES OF METHANOL & DME S.NO DESCRIPTION PAGE 2.2.1.6 Gujarat State Fertilizer Corporation (GSFC) 2.6 2.2.2 India-Imports and Exports 2.6 2.2.3 Domestic Consumption and End Use Patterns 2.7 2.2.3.1 Consumption 2.7 2.2.3.2 End Use Pattern 2.7 2.2.4 Future Demand Forecast of India 2.8 2.3 International Status 2.9 2.3.1 Production 2.9 2.3.2 Future Methanol Capacity 2.11 2.3.3 Global Imports and Exports 2.12 2.4 Global Supply and Demand 2.14 2.4.1 Historical Trend 2.14 2.4.2 Demand Projection 2.16 2.4.3 Demand and End Use Sector 2.18 2.5 Country Scenario 2.22 2.5.1 China 2.22 2.5.2 USA 2.24 2.5.3 Iran 2.26 2.6 Methanol in the European Union 2.27 2.7 Global DME Market 2.31 2.7.1 DME in China 2.31 2.7.2 Major Players in the World 2.34 3.0 CHAPTER-3:METHANOL AND DME UTILIZATION 3.1 3.1 Chemicals from Methanol 3.1 3.1.1 Methanol Specification 3.3 3.2 Formaldehyde 3.4 3.2.1 Technology 3.5 3.2.2 Indian Scenario 3.5 3.2.3 Projected Demand 3.6 2 TIFAC, DST, GOVT. -

Project Bond Focus Issue 4 | Project Bonds: New Energies – Solar

Project Bond Focus Issue 4 | Project Bonds: New Energies – Solar Project Bonds: New Energies – Solar Crédit Agricole CIB, a leader in the global Project Bond market, is authoring a series of articles covering key topics for issuers to consider. New Energies Solar Project Bonds The volume of Project Bonds issued for renewable energy Solar Project Bonds projects has steadily increased in recent years. (Global volume in $MM equivalent) 2,400 The Capital Markets opened its doors to renewable energy 2,200 1,896 2,000 projects with a wind Project Bond in 2003, followed by 1,780 solar Project Bonds a few years later in 2010. 1,800 1,600 1,446 1,284 1,421 These trail-blazing transactions allowed investors to gain 1,400 1,200 1,034 familiarity with the technologies, risks, and contractual 1,000 arrangements related to renewable assets. They also 800 paved the way for future issuances, as rating agencies 600 400 started publishing specific methodologies dedicated to this 258 200 newly accessible asset class. 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Renewables have grown to represent nearly 25% of power Source: PFI, CA CIB Project Bonds and 10% of total Project Bonds issued in just over a decade. In 2015, renewable energy projects Historically, the first solar Project Bond issuance was the accounted for $3.5BN of Project Bond issuances globally. €196MM Andromeda Finance offering for a 51MW utility- scale PV Italian solar project in December 2010. In 2011, Power Project Bonds the $702MM Project Bond for NextEra Genesis Solar, a (Global volume in $MM equivalent) single-site Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) project with a 20,000 capacity of 250MW in California, marked the opening of 15,054 the US Debt Capital Markets for solar projects. -

What Makes Ray Smile?

GEAR SERVICE BUSINESS VOL. 51 • ISSUE 2 FEBRUARY 2015 Skully gets dealer-ready: Hiring ex-cons: How to Rod Stuckey: What’s We talk with the founder think outside the cell your winning formula? DEALERNEWS.COM pg. 28 pg. 30 pg. 34 MARK RODGERS THE PRINCIPLE OF ‘NUDGE’ Coaxing customers through a series of yesses ON STREET YAMAHA SMAX Small scooter fills big shoes Whhaat mmakakes RRayay ssmile?mile? MAN AND BUSINESS THRIVE ON STRUCTURE HISTORY OF THE BRAND Charlie Barnett’s philosophy is alive and well magentablackcyanyellow ES556791_DN0215_cv1.pgs 01.21.2015 19:51 ADV For more information visit www.Dealernews.com/readerservice magentablackcyanyellow ES554727_DN0215_CV2_FP.pgs 01.14.2015 15:53 ADV The Books2015 LARGEST PARTS SELECTION FOR HARLEYS KNUCKLE TO TWIN CAM, AND EVERYTHING IN-BETWEEN Get into the 2015 FatBook™ and OldBook™ — the largest collection of V-Twin parts & accessories from top brands. And connect with Drag Specialties online to keep current with new products, events and bike-builds. WORLDWIDE LEADER IN V-TWIN PARTS SINCE 1968 dragspecialties.com magentablackcyanyellow ES554774_DN0215_001_FP.pgs 01.14.2015 15:55 ADV the DEALERNEWS conversation at blogs.dealernews.com VOLUME 51 | ISSUE 2 | FEBRUARY 2015 8 HISTORY OF THE BRAND: Barnett Tool & Engineering REAR VIEW – Top news from February 1976 12 ·V-TWIN 12 16 COVER STORY: FROM NAVY SPEED READ 2015 Indian BLUE TO HARLEY ORANGE Scout customs... RSD racing EVERY ISSUE Structured processes govern controls... Legend Suspensions Smokin’ Harley-Davidson. updates product lines By Marilyn Stemp 6 FROM THE EDITOR ·ON STREET 20 22 10 MARK RODGERS: YAMAHA SMAX: Small SPEED READ AMA Vintage The Principle of Nudge: How to move cus- scooter fi lling big shoes.. -

Solar Is Driving a Global Shift in Electricity Markets

SOLAR IS DRIVING A GLOBAL SHIFT IN ELECTRICITY MARKETS Rapid Cost Deflation and Broad Gains in Scale May 2018 Tim Buckley, Director of Energy Finance Studies, Australasia ([email protected]) and Kashish Shah, Research Associate ([email protected]) Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... 2 1. World’s Largest Operational Utility-Scale Solar Projects ........................................... 4 1.1 World’s Largest Utility-Scale Solar Projects Under Construction ............................ 8 1.2 India’s Largest Utility-Scale Solar Projects Under Development .......................... 13 2. World’s Largest Concentrated Solar Power Projects ............................................... 18 3. Floating Solar Projects ................................................................................................ 23 4. Rooftop Solar Projects ................................................................................................ 27 5. Solar PV With Storage ................................................................................................. 31 6. Corporate PPAs .......................................................................................................... 39 7. Top Renewable Energy Utilities ................................................................................. 44 8. Top Solar Module Manufacturers .............................................................................. 49 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... -

Solar Power for the Veneto

Photovoltaics Rovigo solaR PRoject Rovigo solar farm and central inverter/transformer station 70 MW of solar power for the Veneto On a foggy November day, SunEdison Italy, its financial partners track record in utility-scale solar plants, using 840 km of cables, 50 km of conduits and more than 6 tons of and local officials inaugurated Europe’s largest solar farm in steel for the metal substructures and the like. Rovigo, Veneto. Hundreds of guests demonstrated the “The polycrystalline panels have been supplied by Canadian Solar, Trina Solar, Yingli and Solarfun,” importance of the project as a reference for its initiators, as well says Liborio Nanni, Country Manager at SunEdison Italia. The last modules were shipped by air cargo di- as a means to support local development. rectly from China, in order to stay within the deadline. “The Rovigo project is important for several reasons, not only for its size,” Pancho Perez, General Manager t first glance, the solar power plant is an exten- of SunEdison EMEA, points out. According to him, ded blue surface equalling a big inland lake in the solar farm is a reference for a quick and precise Asize. Having realised that the object is just a ve- project realisation, as it took only nine months from ry huge solar park, the passer-by can’t help seeing the the beginning of construction to the interconnection central inverter station, which manages the electricity in November 2010. produced and makes it compatible with the national “This milestone has been made possible with the grid. help of perfect timing for installation work and excel- Today, the Rovigo project is the largest European lent cooperation of the partners,” adds Perez, re- PV power plant – bigger than the 60 MW solar farm ferring first of all to financial partners MEMC and in Olmedilla, Spain, and the 50 MW project in SunEdison. -

Marknadsanalys Av Bränsleceller

Marknadsanalys av bränsleceller Jon Sebastian Fjäder Examensarbete Plastteknik 25.05.2016 EXAMENSARBETE Arcada Utbildningsprogram: Plastteknik Identifikationsnummer: 14282 Författare: Jon Sebastian Fjäder Arbetets namn: Marknadsanalys av bränsleceller Handledare (Arcada): Björn Wiberg, amanuens och forskare Uppdragsgivare: Björn Wiberg, amanuens och forskare Abstrakt Examensarbetet handlar om bränslecellernas kommersiella marknad på en global nivå och deras jämförelse med andra energiteknologier. Syftet med arbetet är att få en inblick i marknadens olika aspekter om bränslecellernas applikationer som delats in i tre katego- rier. Kategorierna är stationära, transporterbara och bärbara applikationer. Frågeställning- arna för arbetet är bränslecellernas roll i samhället, hur marknaden har utvecklas för bränsleceller från år 2010 framåt och vilka är marknadssegmenten? Undersökningens in- formation reflekterar data från den kommersiella marknaden och är begränsad till åren 2010-2016. För att få en inblick i den globala energimarknaden har även andra energitek- nologier tagits upp. Dessa är fem stycken, två av dem baserar sig på fossila bränslen och tre på förnybar energi. De är olja, kärnkraft, kolkraft, vindkraft och solkraft. Resultaten från årssammanfattningarna, artiklarna, nyheterna och rapporterna från den globala mark- naden indikerar en ständig ökning inom alla applikationsområden för bränsleceller. I undersökningen beträffande stationära applikationer framkom det att de dominerar bräns- lecellsmarknaden inom alla områden som beaktats för att få information om branschen. För noggrannare information om ett enskilt företag tas resultat ur en undersökning om FuelCell Energy upp, där det bl.a. registrerats konkreta mängder av utsläpp som undvikts genom användningen av elektricitet från bränslecellskraftverk. Inom applikationer av- sedda för transport har tre olika fordon med olika bränslen jämförts med varandra samt det har tagits upp resultat om tankningsstationer för vätedrivna fordon. -

2014 Fuel Cell Technologies Market Report

Fuel Cell Technologies Market Report 2014 (This page intentionally left blank) FUEL CELL TECHNOLOGIES MARKET REPORT 2014 Authors This report was compiled and written by Sandra Curtin and Jennifer Gangi of the Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Energy Association, in Washington, D.C. Acknowledgement The authors relied upon the hard work and valuable contributions of many men and women in government and in the fuel cell industry. The authors especially wish to thank Sunita Satyapal and the staff of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fuel Cell Technologies Office for their support and guidance. Also thanks to Philipp Beiter, Tian Tian, and Jeff Logan of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, and David Hart and Franz Lehner of E4Tech. Notice This report is being disseminated by the Department of Energy. As such, this document was prepared in compli- ance with Section 515 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2001 (Public Law 106-554) and information quality guidelines issued by the Department of Energy. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. Cover Image Cal State L.A. -

Methanol Fuel Cells: Powering the World's Future Energy Needs

Hosted & Organized by Qatar Fuel Additives Company Limited (QAFAC) Methanol Fuel Cells: Powering the World’s Future Energy Needs www.oorjafuelcells.com Renewable Energy Targets in the GCC Deployment of new technologies will enable the region to meet ambitious goals 3 Fuel Cell Technologies 4 Advantages Methanol vs. Hydrogen Hydrogen Fuel Cells Direct Methanol Fuel Cells 6 bottles of Hydrogen enables 1 Drum of Methanol (200 liter) enables 33 hours of backup time at 1.5 kW 200 hours of backup time at 1.5 kW H2 is volatile, requires high pressure or CH3OH delivers efficient energy storage by cryogenic storage in expensive and heavy volume, even compared with compressed H2 to transport containers, and needs at standard 150 bars pressure reduced for fuel cell needs CH3OH is a user friendly, easily transportable, non-explosive liquid and low cost for stationary or mobile storage 5 DMFC: Key Enabler of Methanol Economy Methanol can be made sustainably from: • Agricultural waste • Animal waste; e.g. Smithfield Farms hog waste • Construction waste – lumber, plywood • Forestry and forestry products waste • Municipal solid waste; e.g. Enerkem, Edmonton 40 million liters/year from urban garbage Methanol is available globally used for cooking, heating, lighting, and transportation fuels Oorja delivers methanol based electrical power for global health, education, economy Provides enough power to supplement or supplant diesel gensets and batteries in target markets and applications Miracle Energy on Hand 6 DMFC: Key Enabler of Methanol Economy Methanol Supply/Value Chain CO2: industrial exhaust CH4 & atmospheric CH20 +HCO2H Natural Sources Oxidation Reduction Hydrogenation or Selective Reduction in H20 Oxidation CH3OH Energy Storage & Fuels Synthetic Hydro- Electrical Power – UPS, carbons & Products Cooking & Heating Backup, and Main Lighting Direct Methanol Fuel Cell with H2O by-product Transportation Methanol cooking and heating is especially important for replacement of inside burning of wood, charcoal, coal, etc.