Forestry Kaimin, 1930

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Tools

Know your Landscape Tools Long handled Round Point Shovel A very versatile gardening tool, blade is slightly cured for scooping round end has a point for digging. D Handled Round Point Shovel A versatile gardening tool, blade is slightly cured for scooping round end has a point for digging. Short D handle makes this an excellent choice where digging leverage is needed. Good for confined spaces. Square Shovel Used for scraping stubborn material off driveways and other hard surfaces. Good for moving small gravel, sand, and loose topsoil. Not a digging tool. Hard Rake Garden Rake This bow rake is a multi-purpose tool Good for loosening or breaking up compacted soil, spreading mulch or other material evenly and leveling areas before planting. It can also be used to collect hay, grass or other garden debris. Leaf rake Tines can be metal or plastic. It's ideal for fall leaf removal, thatching and removing lawn clippings or other garden debris. Tines have a spring to them, each moves individually. Scoop Shovel Grain Shovel Has a wide aluminum or plastic blade that is attached to a short hardwood handle with "D" top. This shovel has been designed to offer a lighter tool that does not damage the grain. Is a giant dust pan for landscapers. Edging spade Used in digging and removing earth. It is suited for garden trench work and transplanting shrubs. Generally a 28-inch ash handle with D-grip and open-back blade allows the user to dig effectively. Tends to be heavy but great for bed edging. -

Gardex E Catalogue

index hammers 003 picks & mattocks 057 axes 015 hoes 067 wedges 021 forks 083 mauls 023 wrecking / pry bars 029 forged spades & shovels 087 chisels 035 rakes 093 mason pegs 041 tampers & scrapers 097 bolsters 043 bars 047 slashers 103 Hammers PRODUCT NAME DE CODE CODE CO HANDLES AMERICAN HARDWOOD (AHW) AVAILABLE WEIGHTS AW F 2GF 3GF 4GF AVAILABLE HANDLES ( ) CLUB HAMMER FIBERGLASS (F) 60411085 2G FIBERGLASS (2GF) 3G FIBERGLASS (3GF) 2.5, 4 LBS 4G FIBERGLASS (4GF) AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF 3 Hammers BRASS NON SPARKING HAMMER MACHINIST HAMMER 60411126 60413000 6, 8, 10, 12 LBS AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF CLUB HAMMER CONICAL EYE 60411096 3, 4, 5 KG AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF CROSS PEIN HAMMER 60411070 3, 4, 5 KG 2, 3, 4 LBS AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF 5 Hammers SLEDGE HAMMER STONNING HAMMER (ESP) 60411147 60411015 700, 1000, 1400 GMS AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF ENGINEERING HAMMER 60411000 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20 LBS AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF DRILLING HAMMER 60411058 2, 3, 4 LBS 1, 2, 3, 4 LBS AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF 7 Hammers CLAW HAMMER AMERICAN TYPE TUBULAR CLAW HAMMER 60412041 60412056 16, 20, 24 OZ 16 OZ AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF CLAW HAMMER RIP ALL STEEL CLAW HAMMER 60411212 60412058 16, 20 OZ 16 OZ AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF CARPENTER CLAW HAMMER WITH/WITHOUT MAGNET CLAW HAMMER FR TYPE 60412006 60412000 250, 350, 450 GMS 700 GMS AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF 9 Hammers MACHINIST HAMMER BALL PEIN HAMMER 60411111 60411240 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 32, 40, 48 OZ AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF AHW F 2GF 3GF 4GF STONING HAMMER 60411142 100, 200, 300, 400, -

A History of the Garden in Fifty Tools Bill Laws

A HISTORY OF THE GARDEN IN FIFTY TOOLS BILL LAWS A green thumb is not the only tool one needs to gar- material. We find out that wheelbarrows originated den well—at least that’s what the makers of garden- in China in the second century BC, and their ba- ing catalogs and the designers of the dizzying aisle sic form has not changed much since. He also de- displays in lawn- and-garden stores would have us scribes how early images of a pruning knife appear believe. Need to plant a bulb, aerate some soil, or in Roman art, in the form of a scythe that could cut keep out a hungry critter? Well, there’s a specific through herbs, vegetables, fruits, and nuts and was tool for almost everything. But this isn’t just a prod- believed to be able to tell the gardener when and uct of today’s consumer era, since the very earliest what to harvest. gardens, people have been developing tools to make Organized into five thematic chapters relating planting and harvesting more efficient and to make to different types of gardens: the flower garden, the flora more beautiful and trees more fruitful. In A kitchen garden, the orchard, the lawn, and orna- History of the Garden in Fifty Tools, Bill Laws offers mental gardens, the book includes a mix of horti- entertaining and colorful anecdotes of implements culture and history, in addition to stories featuring that have shaped our gardening experience since well-known characters—we learn about Henry David the beginning. Thoreau’s favorite hoe, for example. -

4.4.27 Ivy, Hedera Helix

4.4.27 Ivy, Hedera helix Summary Ivy is widespread throughout Britain and a component of mixed scrub communities. Being shade tolerant, it will ramble over and under stands of scrub. Where it compromises interest by suppressing regeneration of scrub and herbaceous flora, then management will be required. Distribution and status Ivy is a common plant throughout the whole of Britain and grows on all but the most acidic, very dry or waterlogged soil up to altitudes of 610 m. It is very tolerant of shade and will flourish in the darkest of closed canopy scrub. Identification Flowers: Sep–Nov; Fruit: Dec–Feb. Ivy will climb as well as sprawl over the floor. The stems have fine sucker-like roots that adhere well to any surface. The young stems are downy. The smooth glossy green leaves are darker above and have pale veins. The leaves of non-flowering stems have 3–5 triangular-shaped lobes. On flowering shoots, the leaves are oval to elliptical. Ivy on scree slope. Peter Wakely/English Nature The small greenish yellow flowers only form at the tips of shoots growing in well-lit conditions. The fruit is a small Value to wildlife globular black berry. Valuable to wildlife, for example: Invertebrates: Growth characteristics • 5 species recorded feeding. • Sucker–like roots enable it to attach to most horizontal and vertical substrates. • 2 species feeding exclusively. • Shoots from surface roots, cut and layered stems. • Valuable autumn nectar source. Palatability • A food plant of the Holly Blue butterfly. • Strongly favoured by sheep, especially rams, goats and deer (Roe & Fallow). -

NOTICE: the Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) Governs the Making of Reproductions of Copyrighted Material

NOTICE: The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of reproductions of copyrighted material. One specified condition is that the reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses a reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. RESTRICTIONS: This student work may be read, quoted from, cited, for purposes of research. It may not be published in full except by permission of the author. Jacklight: Stories Table of Contents Jacklight ...................................................................................................................................... 3 The Bacchanal........................................................................................................................... 20 Wothan the Wanderer................................................................................................................ 32 Trickster Shop ........................................................................................................................... 47 Party Games .............................................................................................................................. 57 Coyote Story ............................................................................................................................. 88 2 Jacklight At thirteen, Mary discovered her first rune in a raven’s half-decayed remains. -

Gemini Streaks On; Twins Happy, Healthy

Weather DjUtrfliutlos T«JB, teopenton «. MEDAIIX Todur f d 4 CfCfete f to- d High May la the Mi. 25,000 High tomorrow In U* N*. tvw Red Bank Area tonight, 5». Sunday, fair, warm- I 7 tr, followed by Inwslng ~Y~ Copyright—The Red Bank Register, Inc., 1965. DIAL 741-0010 cloudiness. See weather, page 2. MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOME NEWSPAPER FOR 87 YEARS iHuad dmlly. itmta throurti Trtttj. Second Clm Pontit VOL. 87, NO. 241 pun U JWd But ug at Aduumui Mtiuni ouicu. FRIDAY, JUNE 4, 1965 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE Gemini Streaks On; Twins Happy, Healthy HOUSTON, Tex. (AP) - In- rip the United States hopes'to The astronaut propelled him- "One thing, when Ed gets out difficulty closing the hatch, Mis- trepid astronaut Edward H. make by 1970. self about space with a special there and starts wiggling sion Director Chris Kraft told White II glided out of the Gemi- But- the crowd pleaser Thurs- space gun. around it sure makes the space- newsmen later. As a result, the ni 4 capsule Thursday far a non- day was the space stroll when The order from .Houston Mis- craft tough to control," McDi- space twins were unable to chalant, mischievous walk White, linked to the capsule by sion Control for White to return vitt said soon after the space dump some of the equipment among the stars. a slim golden leash, cavorted in to the capsule was the second walk had begun. that had become surplus after The antics of the sandy-haired the void eight minutes longer time ground control had re- In space there is no resisting the space walk. -

Payette National Forest Recreations/Trails Engineering

Payette National Forest Phase 1 Multiple Seasonal/Temporary Positions Various Series and Grades , Multiple Duty Locations The Payette National Forest offers many Seasonal/Temporary employment opportunities in and around the communities of Weiser, Council, New Meadows, McCall and Yellow Pine. See the list below, then click on the links to see information specific to jobs opportunities. Click one of the following links to jump to your area of interest or peruse at your leisure. Recreations/Trails Engineering Timber Fire Archaeology Biological Science Technician Range Administrative Support Services Recreation/Trails Position Title: Forestry Aid Recreation/Trails (Recreation Focus) GS-0462-03 This position assists in the operations of the Developed Recreation Program. Assignments include routine maintenance of recreation and administrative facilities (i.e. painting, minor repairs, general upkeep, fence building, cleaning of bathrooms and fire rings). Public contact occurs on a daily basis and the employee will support the campground host program by keeping them informed and supplied. Proper use and care of motorized and non-motorized hand tools is required. Employee may act as a collection officer collecting campground fees and selling Forest maps. Furthermore, it may be necessary to occasionally support other recreation programs, such as trail maintenance. The normal work schedule is Wednesday through Sunday and the employee will return to their duty station each day. One position may be filled. Housing may be available, but is not guaranteed. Trails Position Description: Employees would work as part of a three or four person trail crew clearing downfall and brush from multiple-use trails. Other duties will include bridge construction, installing water diversion and tread stabilization structures, installation of signs and kiosks, and maintenance of tools and trail related equipment (pulaski tool, shovel, mattock, rock bar, chainsaw, motorcycles, etc.). -

Oakwood Published by Open PRAIRIE

Department: Oakwood OAK WOOD English & Graphic Design Students Published by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange, 2003 South Dakota State University 1 Arc.h.1 "e.s. f'S S7/ .S� Oakwood, Vol. 2, Iss. 12 [2003], Art. 1 02 2003 c,( Oakwood 2003 is in memory of Audrae Vissar (1919-2001 ): 1948 Graduate of South Dakota State University, Poet Laureate of South Dakota 197 4-2001. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/oakwood/vol2/iss12/1 2 Department: Oakwood F·E AT URE S Winter Hoarfrost ............ ..... ............... ......1 Doug Cockrell Old Poet .......................................... .. .2 Doug Cockrell Winter Forecast ....................................... 3 Doug Cockrel I Miles of Night .................................... .... .4 Doug Cockrel I 1215 Floyd Boulevard .................................. 5 David Allan Evans One-Sided Fist Fight on Lower Fourth .....................6 David Allan Evans POETRY Farmhouse ........................................ ...7 Luke Philippi Liebestraum ...... ... .. ...............................9 Todd VanDerWerff The Death of Mickey Mantle .................. ..........1 O Chad Robinson Elegy ..... ... .......................• ...............11 Todd VanDerWerff Visit to my Grandmother .... .... ...... ......... ........12 Michelle Andrews Gifts of the Abstract ...............................14 -15 Heidi Mayer Mysteriosity .. ....... ............. ................... 17 Patrick Grode Sunlight on a Frosted Windowpane ......... .. ...........18 Katie -

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 04/06/2011 02:26 Pm

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 04/06/2011 02:26 pm WNCU 90.7 FM Format: Jazz North Carolina Central University (Raleigh - Durham, NC) This Period (TP) = 03/30/2011 to 04/05/2011 Last Period (TP) = 03/23/2011 to 03/29/2011 TP LP Artist Album Label Album TP LP +/- Rank Rank Year Plays Plays 1 1 One For All Invades Vancouver Cellar Live 2011 13 15 -2 1 2 Russell Malone Triple Play Max Jazz 2010 13 14 -1 1 3 Jazzvox Jazzvox Presents: In Your OA2 2011 13 13 0 Own Backyard 4 5 Brian Lynch Unsung Heroes Hollistic 2010 12 12 0 4 5 Ernest Stuart Solitary Walker Self-Released 2011 12 12 0 6 3 Kurt Elling The Gate Concord Jazz 2011 11 13 -2 6 16 Tom Rizzo Imaginary Numbers Origin 2010 11 6 5 6 25 Rene Marie Voice Of My Beautiful Motema 2011 11 4 7 Country 9 8 Thomas Marriott Human Spirit Origin 2011 9 10 -1 9 10 Joe Lovano Bird Songs Blue Note 2011 9 9 0 9 13 Delfeayo Marsalis Sweet Thunder Troubadour Jass 2011 9 8 1 12 10 Monty Alexander Uplift JLP 2011 8 9 -1 12 16 Jeremy Pelt Talented Mr. Pelt HighNote 2011 8 6 2 12 18 Eddie Mendenhall Cosine Meets Tangent Miles High 2011 8 5 3 15 25 Mark Weinstein Jazz & Brasil Jazzheads 2010 7 4 3 15 263 Larry Coryell & Kenny Duality Random Act 2011 7 0 7 Drew, Jr. 17 8 Ernestine Anderson Nightlife: Live At Dizzy's HighNote 2011 6 10 -4 Club Coca-Cola 17 10 Matt Nelson Nostalgiamaniac Chicago Sessions 2010 6 9 -3 17 13 Either Orchestra Mood Music For Time Accurate 2010 6 8 -2 Travellers 17 15 Geoffrey Keezer & Peter Mill Creek Road SBE 2011 6 7 -1 Sprague 21 5 Eric Reed The Dancing Monk Savant 2011 5 12 -7 21 25 Bobby Matos Beautiful As The Moon Lifeforce Jazz 2011 5 4 1 21 25 Dado Moroni Live In Beverly Hills Resonance 2011 5 4 1 21 35 Jonathan Kreisberg Shadowless NFN 2011 5 3 2 21 263 Mulgrew Miller Live At Yoshi's Vol. -

Pennsylvania Trail Design & Development Principles

Contents Chapter 4: Construction ....................153 Trail Construction Options ...................................154 Constructing a Trail with In-House Labor .....154 Mechanized Equipment ................................167 Constructing a Trail with Volunteers .............154 Excavators ...............................................167 Pennsylvania Child Labor Laws ...............155 Dozers ......................................................167 Pennsylvania Child Protective Loaders ....................................................167 Services Law ............................................155 Haulers .................................................... 168 Constructing a Trail with a All-Terrain Vehicles and Utility Task Contractor .............................................. 156 Vehicles ................................................... 169 Public Bid ................................................ 156 Trail Construction Options ...................................170 Award of Competitive Bid Contract ...... 156 Field Layout ....................................................170 Purchases Below Bidding Limit ............. 156 Scouting ...................................................170 Constructing a Trail with A Combination Flagging ................................................... 171 of Options ......................................................157 Final Design Work ..........................................172 Preparing to Build Trails ................................157 Trail Clearing ............................................172 -

TV-Contents 11.Pdf

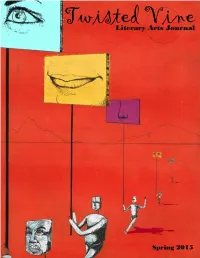

TWISTED VINE LITERARY JOURNAL WESTERN NEW MEXICO UINIVERSITY SPRING 2015 ALL CONTRIBUTORS RETAIN COPYRIGHT TO THEIR RESPECTIVE WORK. THE THOUGHTS AND OPINIONS WITHIN THESE PAGES ARE IN NO WAY REFLECTIVE OF WESTERN NEW MEXICO UNIVERSITY. MASTHEAD: Editors-in-Chief: Caseyrenée Lopez Eric Allen Yankee Assistant Editors: Debra McReynolds Roseanne Kofron Faculty Supervisor: John Gist Website/Social Media Team: Debra McReynolds Becca Knowlton Roseanne Kofron Janeen Thompson Brown Core Readers: Janeen Thompson Brown Dane McCarthy Ryan Crisp Raymond Jurisic Bonita Chavez Eric Allen Yankee Caseyrenée Lopez Cover: The Protests at New Waterloo by: Ege Al'Bege 1 EDITOR’S NOTE: The process of publishing Twisted Vine has exposed me to so many talented writers. My consciousness has been expanded by all these new literary adventures! Thank you so much to the writers and staff who contributed to making this issue of Twisted Vine great. Eric Allen Yankee, Co-Editor in Chief This is one of the largest publishing projects that I’ve had the pleasure of working on, and for that, I am grateful to all of the wonderful writers that have contributed to the spring issue of Twisted Vine and made this possible. I also want to give a big thanks to the awesome staff that were vital in helping us bring this collection together! Cheers to you all! Caseyrenée Lopez, Co-Editor in Chief We at Twisted Vine are proud to present our readers with an eclectic range of work, and are sure that this issue will have something for everyone. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pigeons and Panthers -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Jimmy Rankin – Back Road Paradise • Enrique

Jimmy Rankin – Back Road Paradise Enrique Iglesias – Sex And Love Avicii – True: Avicii By Avicii New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI14-11 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Stompin’ Tom Connors / Unreleased: Songs From The Vault Collection Volume 1 Cat. #: 0253777712 Price Code: SP Order Due: March 6, 2014 Release Date: April 1, 2014 File: Country Genre Code: 16 Box Lot: 25 Tracks / not final sequence 6 02537 77712 9 Tom and Guitar: 12 songs 10. I'll Sail My Ship Alone 1. Blue Ranger 11. When My Blue Moon Turns to Gold 2. Rattlin' Cannonball 12. I Overlooked an Orchid 3. Turkey in The straw ( Instrumental ) 4. John B. Sails Tom Originals with Band: 5. Truck Drivin' Man 1. Cross Canada, aka C.A.N.A.D.A 6. Wild Side of Life 2. My Stompin' Grounds 7. Pawn Shop in Pittsburgh, aka, Pittsburgh 3. Movin' In From Montreal By Train Pennsylvania 4. Flyin' C.P.R. 8. Nobody's Child 5. Ode for the Road 9. Darktown Strutter's Ball This is the Premier Release in an upcoming series of Unreleased Material by Stompin' Tom Connors! In 2011, Tom decided after what ended up being his final Concert Tour, that he would record another 10 album set with a lot of old songs that he sang when he first started out performing in the 50's and 60's.This was back when he could sing, from memory, over 2500 songs in his repertoire and long before he wrote many of his own hits we all know today.