TV-Contents 11.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTICE: the Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) Governs the Making of Reproductions of Copyrighted Material

NOTICE: The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of reproductions of copyrighted material. One specified condition is that the reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses a reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. RESTRICTIONS: This student work may be read, quoted from, cited, for purposes of research. It may not be published in full except by permission of the author. Jacklight: Stories Table of Contents Jacklight ...................................................................................................................................... 3 The Bacchanal........................................................................................................................... 20 Wothan the Wanderer................................................................................................................ 32 Trickster Shop ........................................................................................................................... 47 Party Games .............................................................................................................................. 57 Coyote Story ............................................................................................................................. 88 2 Jacklight At thirteen, Mary discovered her first rune in a raven’s half-decayed remains. -

Forestry Kaimin, 1930

THE FORESTRY KA1MIN 1915-1930 MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY The School of : OF THE State Univ MISSOULA, MONTANA OFFERS to a limited number of students Graduate and Research work to those who can show satisfactory attainment in their undergraduate work in Forestry or who are desirous of completing re search in the forest problems of the Northern Rock ies. An ample equipment and laboratory facilities are provided for research workers. Undergraduate. A four-year course leading to the De gree of Bachelor of Science in Forestry with speciali zation in Public Service Forestry, Logging Engineer ing or Range Management. For information address The School of Forestry STATE UNIVERSITY MISSOULA, MONTANA PLEASE MENTION THE FORESTRY KAIMIN THE FORESTRY KAIMIN 1930 Published Annually by THE FORESTRY CLUB of THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA at , Missoula, Montafia Barry C. Park ............................................... Editor Floyd Phillips and Jack White..........................................-.... Assistant Editors Fred Blaschke and Fred Mass......................................................................... Art John T. Mathews ....................... Sports John F. Aiton Business Manager Lawerence Neff ............................................... Assistant Business Manager Robert Cooney Circulation Manager CONTENTS A New Era In Forest Mapping.......................................................................... 7 The Coyote (Poem)..........................................,......................... 12 The Cork Oak in Its Natural -

Gemini Streaks On; Twins Happy, Healthy

Weather DjUtrfliutlos T«JB, teopenton «. MEDAIIX Todur f d 4 CfCfete f to- d High May la the Mi. 25,000 High tomorrow In U* N*. tvw Red Bank Area tonight, 5». Sunday, fair, warm- I 7 tr, followed by Inwslng ~Y~ Copyright—The Red Bank Register, Inc., 1965. DIAL 741-0010 cloudiness. See weather, page 2. MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOME NEWSPAPER FOR 87 YEARS iHuad dmlly. itmta throurti Trtttj. Second Clm Pontit VOL. 87, NO. 241 pun U JWd But ug at Aduumui Mtiuni ouicu. FRIDAY, JUNE 4, 1965 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE Gemini Streaks On; Twins Happy, Healthy HOUSTON, Tex. (AP) - In- rip the United States hopes'to The astronaut propelled him- "One thing, when Ed gets out difficulty closing the hatch, Mis- trepid astronaut Edward H. make by 1970. self about space with a special there and starts wiggling sion Director Chris Kraft told White II glided out of the Gemi- But- the crowd pleaser Thurs- space gun. around it sure makes the space- newsmen later. As a result, the ni 4 capsule Thursday far a non- day was the space stroll when The order from .Houston Mis- craft tough to control," McDi- space twins were unable to chalant, mischievous walk White, linked to the capsule by sion Control for White to return vitt said soon after the space dump some of the equipment among the stars. a slim golden leash, cavorted in to the capsule was the second walk had begun. that had become surplus after The antics of the sandy-haired the void eight minutes longer time ground control had re- In space there is no resisting the space walk. -

Oakwood Published by Open PRAIRIE

Department: Oakwood OAK WOOD English & Graphic Design Students Published by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange, 2003 South Dakota State University 1 Arc.h.1 "e.s. f'S S7/ .S� Oakwood, Vol. 2, Iss. 12 [2003], Art. 1 02 2003 c,( Oakwood 2003 is in memory of Audrae Vissar (1919-2001 ): 1948 Graduate of South Dakota State University, Poet Laureate of South Dakota 197 4-2001. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/oakwood/vol2/iss12/1 2 Department: Oakwood F·E AT URE S Winter Hoarfrost ............ ..... ............... ......1 Doug Cockrell Old Poet .......................................... .. .2 Doug Cockrell Winter Forecast ....................................... 3 Doug Cockrel I Miles of Night .................................... .... .4 Doug Cockrel I 1215 Floyd Boulevard .................................. 5 David Allan Evans One-Sided Fist Fight on Lower Fourth .....................6 David Allan Evans POETRY Farmhouse ........................................ ...7 Luke Philippi Liebestraum ...... ... .. ...............................9 Todd VanDerWerff The Death of Mickey Mantle .................. ..........1 O Chad Robinson Elegy ..... ... .......................• ...............11 Todd VanDerWerff Visit to my Grandmother .... .... ...... ......... ........12 Michelle Andrews Gifts of the Abstract ...............................14 -15 Heidi Mayer Mysteriosity .. ....... ............. ................... 17 Patrick Grode Sunlight on a Frosted Windowpane ......... .. ...........18 Katie -

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 04/06/2011 02:26 Pm

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 04/06/2011 02:26 pm WNCU 90.7 FM Format: Jazz North Carolina Central University (Raleigh - Durham, NC) This Period (TP) = 03/30/2011 to 04/05/2011 Last Period (TP) = 03/23/2011 to 03/29/2011 TP LP Artist Album Label Album TP LP +/- Rank Rank Year Plays Plays 1 1 One For All Invades Vancouver Cellar Live 2011 13 15 -2 1 2 Russell Malone Triple Play Max Jazz 2010 13 14 -1 1 3 Jazzvox Jazzvox Presents: In Your OA2 2011 13 13 0 Own Backyard 4 5 Brian Lynch Unsung Heroes Hollistic 2010 12 12 0 4 5 Ernest Stuart Solitary Walker Self-Released 2011 12 12 0 6 3 Kurt Elling The Gate Concord Jazz 2011 11 13 -2 6 16 Tom Rizzo Imaginary Numbers Origin 2010 11 6 5 6 25 Rene Marie Voice Of My Beautiful Motema 2011 11 4 7 Country 9 8 Thomas Marriott Human Spirit Origin 2011 9 10 -1 9 10 Joe Lovano Bird Songs Blue Note 2011 9 9 0 9 13 Delfeayo Marsalis Sweet Thunder Troubadour Jass 2011 9 8 1 12 10 Monty Alexander Uplift JLP 2011 8 9 -1 12 16 Jeremy Pelt Talented Mr. Pelt HighNote 2011 8 6 2 12 18 Eddie Mendenhall Cosine Meets Tangent Miles High 2011 8 5 3 15 25 Mark Weinstein Jazz & Brasil Jazzheads 2010 7 4 3 15 263 Larry Coryell & Kenny Duality Random Act 2011 7 0 7 Drew, Jr. 17 8 Ernestine Anderson Nightlife: Live At Dizzy's HighNote 2011 6 10 -4 Club Coca-Cola 17 10 Matt Nelson Nostalgiamaniac Chicago Sessions 2010 6 9 -3 17 13 Either Orchestra Mood Music For Time Accurate 2010 6 8 -2 Travellers 17 15 Geoffrey Keezer & Peter Mill Creek Road SBE 2011 6 7 -1 Sprague 21 5 Eric Reed The Dancing Monk Savant 2011 5 12 -7 21 25 Bobby Matos Beautiful As The Moon Lifeforce Jazz 2011 5 4 1 21 25 Dado Moroni Live In Beverly Hills Resonance 2011 5 4 1 21 35 Jonathan Kreisberg Shadowless NFN 2011 5 3 2 21 263 Mulgrew Miller Live At Yoshi's Vol. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Jimmy Rankin – Back Road Paradise • Enrique

Jimmy Rankin – Back Road Paradise Enrique Iglesias – Sex And Love Avicii – True: Avicii By Avicii New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI14-11 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Stompin’ Tom Connors / Unreleased: Songs From The Vault Collection Volume 1 Cat. #: 0253777712 Price Code: SP Order Due: March 6, 2014 Release Date: April 1, 2014 File: Country Genre Code: 16 Box Lot: 25 Tracks / not final sequence 6 02537 77712 9 Tom and Guitar: 12 songs 10. I'll Sail My Ship Alone 1. Blue Ranger 11. When My Blue Moon Turns to Gold 2. Rattlin' Cannonball 12. I Overlooked an Orchid 3. Turkey in The straw ( Instrumental ) 4. John B. Sails Tom Originals with Band: 5. Truck Drivin' Man 1. Cross Canada, aka C.A.N.A.D.A 6. Wild Side of Life 2. My Stompin' Grounds 7. Pawn Shop in Pittsburgh, aka, Pittsburgh 3. Movin' In From Montreal By Train Pennsylvania 4. Flyin' C.P.R. 8. Nobody's Child 5. Ode for the Road 9. Darktown Strutter's Ball This is the Premier Release in an upcoming series of Unreleased Material by Stompin' Tom Connors! In 2011, Tom decided after what ended up being his final Concert Tour, that he would record another 10 album set with a lot of old songs that he sang when he first started out performing in the 50's and 60's.This was back when he could sing, from memory, over 2500 songs in his repertoire and long before he wrote many of his own hits we all know today. -

Donaldson, Your Full Name and Your Parents’ Names, Your Mother and Father

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. LOU DONALDSON NEA Jazz Master (2012) Interviewee: Louis Andrew “Lou” Donaldson (November 1, 1926- ) Interviewer: Ted Panken with recording engineer Ken Kimery Dates: June 20 and 21, 2012 Depository: Archives Center, National Music of American History, Description: Transcript. 82 pp. [June 20th, PART 1, TRACK 1] Panken: I’m Ted Panken. It’s June 20, 2012, and it’s day one of an interview with Lou Donaldson for the Smithsonian Institution Oral History Jazz Project. I’d like to start by putting on the record, Mr. Donaldson, your full name and your parents’ names, your mother and father. Donaldson: Yeah. Louis Andrew Donaldson, Jr. My father, Louis Andrew Donaldson, Sr. My mother was Lucy Wallace Donaldson. Panken: You grew up in Badin, North Carolina? Donaldson: Badin. That’s right. Badin, North Carolina. Panken: What kind of town is it? Donaldson: It’s a town where they had nothing but the Alcoa Aluminum plant. Everybody in that town, unless they were doctors or lawyers or teachers or something, worked in the plant. Panken: So it was a company town. Donaldson: Company town. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Panken: Were you parents from there, or had they migrated there? Donaldson: No-no. They migrated. Panken: Where were they from? Donaldson: My mother was from Virginia. My father was from Tennessee. But he came to North Carolina to go to college. -

Biggest Little Fur Con 2017

Biggest Little Fur Con 2017 Artwork and fiction inspired by our theme Artwork Credits Page 5 ................................................................................................................. Sirod (FA: sirod) Page 6, 13, 20 .....................................................................................................Tyrnn (@Tyrnn) Page 10 (top) ..................................................................................... Greevixor (FA: greevixor) Page 10 (bottom) ............................................................... Kekswolf (artwork, DA: kekswolf) Avviveria (character, @avviveria) Page 17 ................................................................. Zanna the Dragon (FA: zannathedragon) Page 19 .................................................................................... Paco Briseño (@panda_paco) Page 23, 33 ................................................................................ WolfyWalter (FA: walter9433) Page 29 ............................................................................................................... Peakit (@Peakit) Page 34 ......................................................................................... Dan Ball Jr. (@DanballjrDan) Page 36 ..........................................................Incredible Crocodile (FA: incrediblecrocodile) Cover, pages 2, 9, 16, 21, 24, back cover ..............Shiuk (shiuksalamander.tumblr.com) Thank You To all the artists and authors who contributed to this conbook. To all of our fellow conventions for -

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

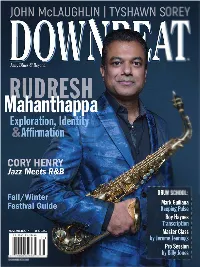

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

Lady Bears Claim No. 2 NCAA Spot

‘WITCH MOUNTAIN’ FAN FARE: CHECK OUT PICTURES ACTION PACKED BUT FIND OUT WHAT BASKETBALL FANS HAD TO FROM LAST WEEK’S LACKS DIALOGUE SAY ABOUT TEAM PERFORMANCES BASKETBALL MANIA PAGE 7 PAGE 8 WWW.BAYLOR.EDU/LARIAT ROUNDING UP CAMPUS NEWS SINCE 1900 THE BAYLOR LARIAT TUESDAY, MARCH 17, 2009 Fight Lady Bears erupts claim No. 2 at local club NCAA spot By Brittany Hardy Staff writer By Joe Holloway about even though they’re clos- Jemar Perot, a 23-year- Sports writer er because we played South old Robinson resident, was Dakota State two or three years stabbed numerous times A day after bringing the ago in the Bahamas and that early Sunday morning, while 2009 Big 12 Tournament was a heck of a ball club then. at Club Legacy. The club is Championship trophy back to They’re very well coached. located at 101 Mill St. in Waco, Waco, the No. 5 Baylor Lady They’re very disciplined. I just about 2.5 miles from Baylor Bears were tabbed Monday as hope it’s so hot in Lubbock campus off Martin Luther a No. 2 seed in the upcom- that they dehydrate.” King Jr Boulevard, accord- ing NCAA women’s basketball Maryland is in the No. 1 ing to Waco police. Officers tournament. spot at the top of the Raleigh arrived at the club’s parking They will take on the No. bracket. After Baylor is No. 3 lot around 2 a.m. where they 15 seed University of Texas at seed Louisville, a team that observed a fight in progress. -

Izu-Ltck\ Chair, Department of English

To the root: adopted memoirs of a Samoan princess in exile Item Type Thesis Authors Hassel, Jody Marie Download date 01/10/2021 06:09:46 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/11317 TO THE ROOT: ADOPTED MEMOIRS OF A SAMOAN PRINCESS IN EXILE By Jody Marie Hassel RECOMMENDED: Advisor)' Committee Chair iZU-LtCk\ Chair, Department of English APPROVED: TO THE ROOT: ADOPTED MEMOIRS OF A SAMOAN PRINCESS IN EXILE A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS By Jody Marie Hassel, B.A. Fairbanks, Alaska December 2012 Ill Abstract To the Root: Adopted Memoirs of a Samoan Princess in Exile traces the author’s eventful search for and reunion with members of biological family In a memoir of personal essays. The author’s search for her birthfather explores thematic elements of loss, abandonment, cultural identity, racial identity, and reconciliation. The memoir explores and challenges boundaries of creative nonfiction through a mosaic of extended narrative scenes and lyric personal reflection. Autobiographical scenes convey the author’s family life and upbringing in Interior Alaska tracing her journey through to adulthood, when she travels to Samoa to receive a traditional rite-of-passage tattoo and familial royal title. Resisting an entirely linear retelling of accounts, impressionist reflections on yoga and Polynesian dance are connected to the author’s experience of adoption. To the Root reaches a deeper understanding of self as adoptee, as daughter, as agent of lineage. iv Dedicated to Joan Marie Braley, Gerald Lee Hassel, and Diana Marie Hunter and in memory of Seagai Saimana Faumuina v Table of Contents Page Signature Page ............................................................................................................................ -

Groove Label Discography

RCA Discography Part 56 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan Groove Label Discography In 1953, RCA diversified their record operations by establishing three new record labels. RCA Victor remained the main pop and classical label. They established a budget label called Camden. A new wholly owned subsidiary called “X” Label was established. A new R & B oriented label called Groove Records was established. Groove Records, which was to be RCA’s new R&B label, was formally introduced in January 1954 with its first releases in February 1954. Bob Rolontz was the head of the label. Unlike “X”, which was designed to operate independently of RCA except that RCA record plants pressed its records, Groove’s primary distribution came through RCA channels. The purpose of the label was to move into the R&B field with black artists. The original incarnation of Groove was folded into the Vik label in early 1957. The artists were transferred to the Vik label. The Groove label was reestablished in 1961 with singles and there were one or two albums issued in 1964. This second incarnation of the Groove ended in 1965. Groove Label 1950s Series Discography: The Groove label was light green with black printing. “GROOVE” in black above the center hole. LG 1000 - Rock That Beat - Boots Brown and his Blockbusters and Dan Drew and his Daredevils [10/55] Boots Brown and the Blockbusters were actually jazz musicians Shelly Manne, Gerry Mulligan and Shorty Rogers, Dan Drew and his Daredevils were actually jazz musicians Al Cohn, Elliot Lawrence and Nick Travis.