Izu-Ltck\ Chair, Department of English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INFLUENCE Music Marketing Meets Social Influencers COVERFEATURE

06-07 Tools Kombie 08-09 Campaigns YACHT, Radiohead, James Blake 10-14 Behind The Campaign Aurora MAY 18 2016 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 157 UNDER THE INFLUENCE music marketing meets social influencers COVERFEATURE In the old days, there were a handful of gatekeepers – press, TV and radio – and getting music in front of them was hard, UNDER THE INFLUENCE but not impossible. Today, traditional media still holds significant power, but the number of influencers out there has shot up exponentially with the explosion of social media in general and YouTube in particular. While the world’s largest video service might be under fire over its (low) royalty rates, the music industry is well aware that its biggest stars offer a direct route to the exact audiences they want their music to reach. We look at who these influencers are, how they can be worked with and the things that will make them back or blank you. etting your act heard used to be, if not exactly easy, then at least relatively Gstraightforward for the music business: you’d schmooze the radio playlist heads, take journalists out to a gig and pray for some TV coverage, all while splashing out on magazine and billboard advertising. The digital era – and especially social media – have shaken this all up. Yes, traditional media is still important; but to this you can add a sometimes bewildering list of “social influencers”, famous faces on platforms like YouTube, Snapchat and Instagram, plus vloggers, Viners and the music marketing meets rest, all of whom (for now) wield an uncanny power over youthful audiences. -

Louis Nicholas Song Collection

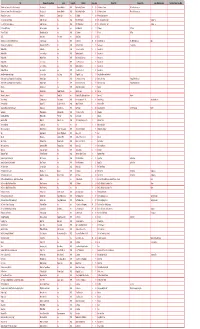

Title Composer/Arranger/Editor Lyricist Copyright Publisher Pages Box Original Title Translated Title Larger Work/Collection Translated Title of Large Work A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La) Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La), c.2 Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Notre Dame sous-terre Chatillon, E. Chastel, Guy n/a E. Chatillon 7 30 A Notre Dame sous-terre A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora, c.2 Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Trianon (At Trianon) Holmes, Augusta n/a n/a Harch Music Co. 4 19 A Trianon At Trianon A Vous (To Thee) D'Hardelot and Boyer n/a 1895 G. Schirmer 4 17 A Vous To Thee A.B.C. Parry, John Parry, John n/a Oliver Ditson 5 23 A.B.C. Abborrita rivale, L' (She, My Rival Detested) Verdi, Giuseppe n/a 1915 G. Schirmer 10 28 Abborrita rivale, L' She, My Rival Detested Aida Abendsegen (Evening-Prayer) Humperdinck and Wette n/a 1894 B. Schott's Sohne 2 28 Abendsegen Evening-Prayer Abide with Me Ashford, E.L. -

Shoosh 800-900 Series Master Tracklist 800-977

SHOOSH CDs -- 800 and 900 Series www.opalnations.com CD # Track Title Artist Label / # Date 801 1 I need someone to stand by me Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 2 A thousand miles away Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 3 You don't own your love Nat Wright & Singers ABC-Paramount 10045 1959 801 4 Please come back Gary Warren & Group ABC-Paramount 9861 1957 801 5 Into each life some rain must fall Zilla & Jay ABC-Paramount 10558 1964 801 6 (I'm gonna) cry some time Hoagy Lands & Singers ABC-Paramount 10171 1961 801 7 Jealous love Bobby Lewis & Group ABC-Paramount 10592 1964 801 8 Nice guy Martha Jean Love & Group ABC-Paramount 10689 1965 801 9 Little by little Micki Marlo & Group ABC-Paramount 9762 1956 801 10 Why don't you fall in love Cozy Morley & Group ABC-Paramount 9811 1957 801 11 Forgive me, my love Sabby Lewis & the Vibra-Tones ABC-Paramount 9697 1956 801 12 Never love again Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 13 Confession of love Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10341 1962 801 14 My heart V-Eights ABC-Paramount 10629 1965 801 15 Uptown - Downtown Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 16 Bring back your heart Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10208 1961 801 17 Don't restrain me Joe Corvets ABC-Paramount 9891 1958 801 18 Traveler of love Ronnie Haig & Group ABC-Paramount 9912 1958 801 19 High school romance Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 20 I walk on Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 21 I found a girl Scott Stevens & The Cavaliers ABC-Paramount -

Amy Macdonald

Amy Macdonald Auch wenn man sie vielleicht weniger in der Öffentlichkeit sieht, kaum etwas von ihr mitkriegt, kann man sich sicher sein, dass Amy Macdonald irgendwo bei der Arbeit ist. Selbst wenn es eine ganze Weile her zu sein scheint, dass die preisgekrönte Singer/Songwriterin und ihre vielen, vielen Hits im Radio quasi omnipräsent waren, absolviert die Schottin nach wie vor Auftritte vor riesigen Menschenmengen – denn ihr Name steht auf den Plakaten der großen europäischen Festivals noch immer ganz oben. Ja, selbst wenn sie sich vornimmt, doch mal eine richtige Auszeit zu nehmen, wird daraus in der Regel nichts, denn entweder wird sie gebeten, ihre Nation bei irgendwelchen Großveranstaltungen zu vertreten, oder ihr juckt es einfach doch mal wieder zu sehr unter den Songwriter-Fingernägeln. Es stimmt zwar, dass Amy Macdonald inzwischen auf ein ganzes erfolgreiches Jahrzehnt in der Musikwelt zurückblicken kann. Aber man darf auch nicht vergessen, dass sie noch immer keine dreißig ist. Das nicht selten verwendete Wort “Ausnahmetalent” trifft es in ihrem Fall tatsächlich: Denn Amy Macdonald ist eine Musikerin, die ein absolut natürliches Melodiegespür hat, deren nächster Hit ihr quasi immer schon auf der Zunge, auf den Lippen zu liegen scheint. Auch ganz klar die Ausnahme: Dass sie als Britin in allen Ecken der Welt dermaßen erfolgreich werden sollte. Und gerade in dem Moment, als man dachte, sie sei von der Bildfläche verschwunden, kehrte sie mit einer Killer-Performance beim Montreux Jazz Festival zurück: Ein Auftritt, der verewigt wurde auf einem circa fußballtorgroßen Poster, das einen nun “schon etwa fünf Jahre lang” in der Ankunftshalle des Genfer Flughafens begrüßt, wie sie lachend erzählt. -

Record-World-1980-01

111.111110. SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS KOOL & THE GANG, "TOO HOT" (prod. by THE JAM, "THE ETON RIFLES" (prod. UTOPIA, "ADVENTURES IN UTO- Deodato) (writers: Brown -group) by Coppersmith -Heaven) (writer:PIA." Todd Rundgren's multi -media (Delightful/Gang, BMI) (3:48). Weller) (Front Wheel, BMI) (3:58). visions get the supreme workout on While thetitlecut fromtheir This brash British trio has alreadythis new album, originally written as "Ladies Night" LP hits top 5, topped the charts in their home-a video soundtrack. The four -man this second release from that 0land and they aim for the same unit combineselectronicexperi- album offers a midtempo pace success here with this tumultu- mentation with absolutely commer- with delightful keyboards & ousrocker fromthe"Setting cialrocksensibilities.Bearsville vocals. De-Lite 802 (Mercury). Sons" LP. Polydor 2051. BRK 6991 (WB) (7.98). CHUCK MANGIONE, "GIVE IT ALL YOU MIKE PINERA, "GOODNIGHT MY LOVE" THE BABYS, "UNION JACK." The GOT" (prod. by Mangione) (writ- (prod. by Pinera) (writer: Pinera) group has changed personnel over er: Mangione) (Gates, BMI) (3:55). (Bayard, BMI) (3:40). Pinera took the years but retained a dramatic From his upcoming "Fun And the Blues Image to #4 in'70 and thundering rock sound through- Games" LP is this melodic piece withhis "Ride Captain,Ride." out. Keyed by the single "Back On that will be used by ABC Sports He's hitbound again as a solo My Feet Again" this new album in the 1980 Winter Olympics. A actwiththistouchingballad should find fast AOR attention. John typically flawless Mangione work- that's as simple as it is effective. -

Jan 2018 Newsletter

July 2018 2018 JULY SUNDAY FIRST DAY OF WEEK Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday July Birthdays 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 Nevada Davis-July 1 Office Closed Food Day 1 Helen Sutton-July 3 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 Mary Wainwright-July 7 Johnny Gilliam-July 21 Lorece Tettleton-July 21 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 * Food Day 2 Please remember to bring in your 2018 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 social security earnings statement to re-register for your food box 29 30 31 01 02 03 04 TRIAD of Union Parish 710 Holder Road U.S. Postage Paid Farmerville, LA 71241 Non-Profit Organization (318) 368-0469 Permit No. 25 Farmerville, LA 71241 This institution is an equal opportunity provider Is Sleeping a Problem? Remember the Saddle Oxfords? Make your own--- Your sleeping position can influence your health in the inexpensive way-- with a pair of cheap white many ways. It can relieve your back pain or possibly cause tennis shoes and markers from the dollar store. You it, it can make you snore, it can cause neck discomfort, can even get creative and do them in a different color and it can also affect your level of energy in the morning. or make them wingtips, etc. Have fun with this These are some of the of various sleeping positions creative craft and show off your talent! and their effects: • On Your Stomach: This can be a reason for your neck and back pain. • On Your Back: This position makes snoring worse, but it may also cause lower back pain. -

The BG News February 16, 1990

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-16-1990 The BG News February 16, 1990 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 16, 1990" (1990). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5043. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5043 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. FEATURED PHOTOS ICERS HOST FLAMES BG News photographers BG looks to clinch Q show off their best Friday Mag third-place CCHA finish Sports p.9 The Nation *s Best College Newspaper Weather Friday Vol.72 Issue 84 February 16,1990 Bowling Green, Ohio High48c The BG News Low 30° BRIEFLY Hall arson Plant's layoffs delayed arrest made Automotive sales slump, but Chrysler pushes back plan CAMPUS TOLEDO (AP) - Indefinite uled to shut down for a week. by Michelle Matheson layoffs of 724 workers at Chrysler "I know a lot of The two plants, which manufac- staff writer ture Cherokees and Grand Wa- Map grant received: The Corp.'s Jeep plants have been people think the goneers, employ 5,300 people. pushed back two weeks, and some Chrysler has said the layoffs are University's map-making class will A resident of Founders Quadrangle was ar- workers said Thursday they hope plant is eventually soon be charting a new course thanks the layoffs can be avoided all due to slumping automotive sales. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Box London www.karaokebox.co.uk 020 7329 9991 Song Title Artist 22 Taylor Swift 1234 Feist 1901 Birdy 1959 Lee Kernaghan 1973 James Blunt 1973 James Blunt 1983 Neon Trees 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince If U Got It Chris Malinchak Strong One Direction XO Beyonce (Baby Ive Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Cant Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Everybody's Gotta Learn Sometime) I Need Your Loving Baby D (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Wont You Play) Another Somebody… B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The World England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina And The Diamonds (I Love You) For Sentinmental Reasons Nat King Cole (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (Ill Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Reflections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Keep Feeling) Fascination The Human League (Maries The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Meet) The Flintstones B-52S (Mucho Mambo) Sway Shaft (Now and Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Sittin On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (The Man Who Shot) Liberty Valance Gene Pitney (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We Want) The Same Thing Belinda Carlisle (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1 2 3 4 (Sumpin New) Coolio 1 Thing Amerie 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus -

NOTICE: the Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) Governs the Making of Reproductions of Copyrighted Material

NOTICE: The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of reproductions of copyrighted material. One specified condition is that the reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses a reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. RESTRICTIONS: This student work may be read, quoted from, cited, for purposes of research. It may not be published in full except by permission of the author. Jacklight: Stories Table of Contents Jacklight ...................................................................................................................................... 3 The Bacchanal........................................................................................................................... 20 Wothan the Wanderer................................................................................................................ 32 Trickster Shop ........................................................................................................................... 47 Party Games .............................................................................................................................. 57 Coyote Story ............................................................................................................................. 88 2 Jacklight At thirteen, Mary discovered her first rune in a raven’s half-decayed remains. -

Forestry Kaimin, 1930

THE FORESTRY KA1MIN 1915-1930 MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY The School of : OF THE State Univ MISSOULA, MONTANA OFFERS to a limited number of students Graduate and Research work to those who can show satisfactory attainment in their undergraduate work in Forestry or who are desirous of completing re search in the forest problems of the Northern Rock ies. An ample equipment and laboratory facilities are provided for research workers. Undergraduate. A four-year course leading to the De gree of Bachelor of Science in Forestry with speciali zation in Public Service Forestry, Logging Engineer ing or Range Management. For information address The School of Forestry STATE UNIVERSITY MISSOULA, MONTANA PLEASE MENTION THE FORESTRY KAIMIN THE FORESTRY KAIMIN 1930 Published Annually by THE FORESTRY CLUB of THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA at , Missoula, Montafia Barry C. Park ............................................... Editor Floyd Phillips and Jack White..........................................-.... Assistant Editors Fred Blaschke and Fred Mass......................................................................... Art John T. Mathews ....................... Sports John F. Aiton Business Manager Lawerence Neff ............................................... Assistant Business Manager Robert Cooney Circulation Manager CONTENTS A New Era In Forest Mapping.......................................................................... 7 The Coyote (Poem)..........................................,......................... 12 The Cork Oak in Its Natural -

Gemini Streaks On; Twins Happy, Healthy

Weather DjUtrfliutlos T«JB, teopenton «. MEDAIIX Todur f d 4 CfCfete f to- d High May la the Mi. 25,000 High tomorrow In U* N*. tvw Red Bank Area tonight, 5». Sunday, fair, warm- I 7 tr, followed by Inwslng ~Y~ Copyright—The Red Bank Register, Inc., 1965. DIAL 741-0010 cloudiness. See weather, page 2. MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOME NEWSPAPER FOR 87 YEARS iHuad dmlly. itmta throurti Trtttj. Second Clm Pontit VOL. 87, NO. 241 pun U JWd But ug at Aduumui Mtiuni ouicu. FRIDAY, JUNE 4, 1965 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE Gemini Streaks On; Twins Happy, Healthy HOUSTON, Tex. (AP) - In- rip the United States hopes'to The astronaut propelled him- "One thing, when Ed gets out difficulty closing the hatch, Mis- trepid astronaut Edward H. make by 1970. self about space with a special there and starts wiggling sion Director Chris Kraft told White II glided out of the Gemi- But- the crowd pleaser Thurs- space gun. around it sure makes the space- newsmen later. As a result, the ni 4 capsule Thursday far a non- day was the space stroll when The order from .Houston Mis- craft tough to control," McDi- space twins were unable to chalant, mischievous walk White, linked to the capsule by sion Control for White to return vitt said soon after the space dump some of the equipment among the stars. a slim golden leash, cavorted in to the capsule was the second walk had begun. that had become surplus after The antics of the sandy-haired the void eight minutes longer time ground control had re- In space there is no resisting the space walk. -

Philippines Suppliers by Region Batangas (38) Bulacan (92) Cavite (146) Cebu (540)

Global Suppliers Catalog - Sell147.com 6884 Philippines Suppliers By Region Batangas (38) Bulacan (92) Cavite (146) Cebu (540) Cebu, Philippines (36) Davao del Norte (35) Davao del Sur (150) Laguna (197) Leyte (30) Luzon (33) Manila (500) Metro Manila (1101) Metro Manila, Philippines (38) Mindanao (37) misamis oriental (44) Mm (38) NCR (343) Negros Occidental (34) pampanga (105) Philippines (6884) Quezon City (40) Rizal (144) Zambales (48) Updated: 2014/11/30 Philippines Suppliers Company Name Business Type Total No. Employees Year Established Annual Output Value karen pagayon native bags Distributor/Wholesaler - - - Philippines manila Quezon city Cost U Less - furniture & interior solutions Distributor/Wholesaler 51 - 100 People 2008 - Office Table,Office Chair,Workstation,Window Blinds ,Carpets Other Philippines Metro Manila Makati Faith Achieve Plastics Corporation Plastic Packaging Bags,Plastic Bag,shopping bag,retail bag,food packaging Manufacturer 51 - 100 People 2010 - Philippines Cavite Cavite City MARZUQA FRUIT AND SEAFOODS PRODUCTS AND TRADING CO. Trading Company 5 - 10 People 2002 - FRUITS,BANANA, SEAFOODS PRODUCTS,FISH,MINING PRODUCTS Distributor/Wholesaler Philippines Philippines Zamboanga City Sudkarnology Trading Food Products Trading Company Fewer than 5 People 2012 - Philippines Metro Manila Caloocan City Buco Corporation Coconut Cream Powder,Coconut Cream,Coconut Milk,Desiccated Coconut,Sugar Toas Manufacturer 51 - 100 People 1986 - ted Coco Bits Philippines Metro Manila MAKATI CITY Roel Naupal International Trading Trading Company Logs/Lumber,Oils,Flour,Stones, Vehicles Buying Office Fewer than 5 People 2013 - Philippines Metro Manila Quezon City Agent Gatessoft Corp . Property Management System Other - - - Philippines SEACOM, INC. Manufacturer solar heaters,heat pumps,water tanks ,engines,burners and boilers,eletric heater,gener Trading Company 51 - 100 People 1951 - ators,rice milling system,irrigation hose,calorifiers,LED,solar ..