Rhythm, Image, and Voice in Russian Modernist Poetry and Theory 1905-1924

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 24 January 2017 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Harding, J. (2015) 'European Avant-Garde coteries and the Modernist Magazine.', Modernism/modernity., 22 (4). pp. 811-820. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 Publisher's copyright statement: Copyright c 2015 by Johns Hopkins University Press. This article rst appeared in Modernism/modernity 22:4 (2015), 811-820. Reprinted with permission by Johns Hopkins University Press. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine Jason Harding Modernism/modernity, Volume 22, Number 4, November 2015, pp. 811-820 (Review) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/605720 Access provided by Durham University (24 Jan 2017 12:36 GMT) Review Essay European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine By Jason Harding, Durham University MODERNISM / modernity The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist VOLUME TWENTY TWO, Magazines: Volume III, Europe 1880–1940. -

Fyodor Sologub - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Fyodor Sologub - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Fyodor Sologub(1 March 1863 – 5 December 1927) Fyodor Sologub was a Russian Symbolist poet, novelist, playwright and essayist. He was the first writer to introduce the morbid, pessimistic elements characteristic of European fin de siècle literature and philosophy into Russian prose. <b>Early Life</b> Sologub was born in St. Petersburg into the family of a poor tailor, Kuzma Afanasyevich Teternikov, who had been a serf in Poltava guberniya, the illegitimate son of a local landowner. His father died of tuberculosis in 1867, and his illiterate mother was forced to become a servant in the home of the aristocratic Agapov family, where Sologub and his younger sister Olga grew up. Seeing how difficult his mother's life was, Sologub was determined to rescue her from it, and after graduating from the St. Petersburg Teachers' Institute in 1882 he took his mother and sister with him to his first teaching post in Kresttsy, where he began his literary career with the 1884 publication in a children's magazine of his poem "The Fox and the Hedgehog" under the name Te-rnikov. Sologub continued writing as he relocated to new jobs in Velikiye Luki (1885) and Vytegra (1889), but felt that he was completely isolated from the literary world and longed to be able to live in the capital again; nevertheless, his decade-long experience with the "frightful world" of backwoods provincial life served him well when he came to write The Petty Demon. -

Cubism (Surface—Plane), 1912

perished because of a negative and exclusive solution to the question of shading. Our age is obliged by force of circumstances to finish what our predeces- sors passed on to us. The path of search in this direction is broad, its bends are diverse, its forks numerous; the solutions will be many. Among them, those connected in our art with the name of A. Exter will remain as an ex- ample of courage, freedom, and subtlety. The upsurge of strength and courage in the plastic arts wanes neither beyond the Rhine nor at home, and it is expressed in the high level of pure painting unprecedented in our coun- try, a phenomenon that is characteristic of its contemporary state. DAVID BURLIUK Cubism (Surface—Plane), 1912 For biography see p. 8. The text of this piece, "Kubizm," is from an anthology of poems, prose pieces, and articles, Poshchechina obshchestvennomu vkusu [A Slap in the Face of Public Taste] (Moscow, December 1912 [according to bibl. R350, p. 17, although January 1913, according to KL], pp. 95-101 [bibl. R275]. The collection was prefaced by the famous declaration of the same name signed by David Burliuk, Velimir Khlebni- kov, Aleksei Kruchenykh, and Vladimir Mayakovsky and dated December 1912. The volume also contained a second essay by David Burliuk on texture [bibl. R269], verse by Khlebnikov and Benedikt Livshits, and four prose sketches by Vasilii Kan- dinsky [for further details see bibl. 133, pp. 45-50]. Both the essay on cubism and the one on texture were signed by N. Burliuk, although it is obvious that both were written by David and not by Nikolai (David's youngest brother and a poet of some merit). -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

From%20Irina%20Reyman%2C%20Ritualized%20Violence

PHYSICAL INVIOLABILITY AND THE DUEL pUNCH OR STAB: THE RUSSIAN DUELIST’S DILEMMA The Russian duel was a surprisingly and consistently violent affair. I do not imply that Russian duels were more deadly than those in the West (the fatality rate in Russia never approached that in France in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries or in Germany at the end of the nineteenth century).1 I mean rather that conflicts over honor were frequently resolved in unregu lated spontaneous physical confrontations rather than in formal en- counters . Furthermore, those confrontations differed from rencontres in that they involved direct physical contact—hand-to-hand fighting or the use of weapons unrecognized by the dueling ritual, such as walking sticks or whips. The use of standard dueling weapons— swords or pistols—appears to have been optional. In other words, from the introduction of the duel in Russia to its demise, a conflict over honor was as likely (and at times more likely) to result in an im mediate and violent hand-to-hand fight as in a formal duel of honor. This happened so frequently that physical force seems to have been an accepted alternative to the duel. In fact, it would be possible to write (—S A Brief History of Dueling in Russia 97 98 a variant history of dueling in Russia featuring fistfights, slaps in the Everyone present—nobles face, and battering with walking sticks. and commoners, officers and enlisted men, Historians of the Russian women too—had at each other. Klimovich’s wife was beaten with a duel have consistently ignored or dis missed this ugly and violent club and her mother threatened.4 Grinshtein seems to have won this alternative behavior as aberrant. -

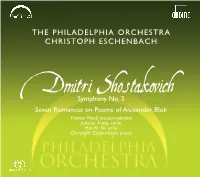

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

Modernist Ekphrasis and Museum Politics

1 BEYOND THE FRAME: MODERNIST EKPHRASIS AND MUSEUM POLITICS A dissertation presented By Frank Robert Capogna to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2017 2 BEYOND THE FRAME: MODERNIST EKPHRASIS AND MUSEUM POLITICS A dissertation presented By Frank Robert Capogna ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2017 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the public art museum and its practices of collecting, organizing, and defining cultures at once enabled and constrained the poetic forms and subjects available to American and British poets of a transatlantic long modernist period. I trace these lines of influence particularly as they shape modernist engagements with ekphrasis, the historical genre of poetry that describes, contemplates, or interrogates a visual art object. Drawing on a range of materials and theoretical formations—from archival documents that attest to modernist poets’ lived experiences in museums and galleries to Pierre Bourdieu’s sociology of art and critical scholarship in the field of Museum Studies—I situate modernist ekphrastic poetry in relation to developments in twentieth-century museology and to the revolutionary literary and visual aesthetics of early twentieth-century modernism. This juxtaposition reveals how modern poets revised the conventions of, and recalibrated the expectations for, ekphrastic poetry to evaluate the museum’s cultural capital and its then common marginalization of the art and experiences of female subjects, queer subjects, and subjects of color. -

Modernism & Modernist Literature: Introduction

MODERNISM & MODERNIST LITERATURE: INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND INTRODUCTION Broadly speaking, ‘modernism’ might be said to have been characterised by a deliberate and often radical shift away from tradition, and consequently by the use of new and innovative forms of expression Thus, many styles in art and literature from the late 19th and early 20th centuries are markedly different from those that preceded them. The term ‘modernism’ generally covers the creative output of artists and thinkers who saw ‘traditional’ approaches to the arts, architecture, literature, religion, social organisation (and even life itself) had become outdated in light of the new economic, social and political circumstances of a by now fully industrialised society. Amid rapid social change and significant developments in science (including the social sciences), modernists found themselves alienated from what might be termed Victorian morality and convention. They duly set about searching for radical responses to the radical changes occurring around them, affirming mankind’s power to shape and influence his environment through experimentation, technology and scientific advancement, while identifying potential obstacles to ‘progress’ in all aspects of existence in order to replace them with updated new alternatives. All the enduring certainties of Enlightenment thinking, and the heretofore unquestioned existence of an all-seeing, all-powerful ‘Creator’ figure, were high on the modernists’ list of dogmas that were now to be challenged, or subverted, perhaps rejected altogether, or, at the very least, reflected upon from a fresh new ‘modernist’ perspective. Not that modernism categorically defied religion or eschewed all the beliefs and ideas associated with the Enlightenment; it would be more accurate to view modernism as a tendency to question, and strive for alternatives to, the convictions of the preceding age. -

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia © 2014 Brad Alexander Gordon A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi April, 2014 Approved: Advisor: Dr. Joshua First Reader: Dr. William Schenck Reader: Dr. Valentina Iepuri 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………p. 3 Part I: Interwar Émigrés and Their Literary Contributions Introduction: The Russian Intelligentsia and the National Question………………….............................................................................................p. 4 Chapter 1: Russia’s Eschatological Quest: Longing for the Divine…………………………………………………………………………………p. 14 Chapter 2: Nature, Death, and the Peasant in Russian Literature and Art……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 26 Chapter 3: Tsvetaeva’s Tragedy and Tolstoi’s Triumph……………………………….........................................................................p. 36 Part II: The Émigrés Return Introduction: Nostalgia’s Role in Contemporary Literature and Film……………………………………………………………………………………p. 48 Chapter 4: “Old Russia” in Contemporary Literature: The Moral Dilemma and the Reemergence of the East-West Debate…………………………………………………………………………………p. 52 Chapter 5: Restoring Traditional Russia through Post-Soviet Film: Nostalgia, Reconciliation, and the Quest -

The T Ransrational Poetry of Russian Futurism Gerald J Ara,Tek

The T ransrational Poetry of Russian Futurism E Gerald J ara,tek ' 1996 SAN DIEGO STATE UNIVERSilY PRESS Calexico Mexicali Tijuana San Diego Copyright © 1996 by San Diego State University Press First published in 1996 by San Diego State University Press, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, California 92182-8141 http:/fwww-rohan.sdsu.edu/ dept/ press/ All rights reserved. -', Except for brief passages quoted in a review, no part of thisb ook m b ay e reproduced in an form, by photostat, microfilm, xerography r y , o any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, withoutthe written permission of thecop yright owners. Set in Book Antiqua Design by Harry Polkinhorn, Bill Nericcio and Lorenzo Antonio Nericcio ISBN 1-879691-41-8 Thanks to Christine Taylor for editorial production assistance 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Acknowledgements Research for this book was supported in large part by grants in 1983, 1986, and 1989 from the International Research & Ex changes Board (IREX), with funds provided by the National En dowment for the Humanities, the United States Information Agency, and the US Department of State, which administers the Russian, Eurasian, and East European Research Program (Title VIII). In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to the fol lowing institutions and their staffs for aid essential in complet ing this project: the Fulbright-Bayes Senior Scholar Research Program for further support for the trips in 1983 and 1989, the American Council of Learned Societies for further support for the trip in 1986, the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the Brit ish Library; iri Moscow: to the Russian State Library, the Rus sian State Archive of Literature and Art, the Gorky Institute of World Literature, the State Literary Museum, and the Mayakovsky Museum; in St. -

German Sound Poetry from the Neo-Avant-Garde to the Digital Age

Claudia Benthien & Wiebke Vorrath German sound poetry from the neo-avant-garde to the digital age www.soundeffects.dk SoundEffects | vol. 7 | no. 1 | 2017 issn 1904-500X Benthien & Vorrath: German sound poetry [...] SoundEffects | vol. 7 | no. 1 | 2017 Abstract This article gives insight into German-language sound poetry since the 1950s. The first sec- tion provides a brief historical introduction to the inventions of and theoretical reflections on sound poetry within the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century. The second section presents works by Ernst Jandl and Gerhard Rühm as examples of verbal poetry of the post-war neo-avant-garde. The following two sections investigate contemporary sound poetry relating to avant-garde achievements. Section three deals with two examples that may be classified as sound poetry in a broader sense: Thomas Kling’s poem broaches the issue of sound in its con- tent and vocal performance, and Albert Ostermaier’s work offers an example of verbal poetry featured with music. The fourth section presents recent sound poetry by Nora Gomringer, Elke Schipper and Jörg Piringer, which are more distinctive examples relating to avant-garde poetry genres and use recording devices experimentally. Introduction The article will investigate different periods and types of German-language sound poetry from the post-war era to the present. It is intended as an overview with several short close-readings of different sound-poetic works. To start with a work- ing definition: ‘Our understanding of sound poetry is a poetic work that renounces the word as a bearer of meaning and creates aesthetic structures (sound poems, sound texts) by methodologically adding and composing sounds (series or groups of sounds) driven by their own laws and subjective intentions of expression, and which requires an acoustic realization on behalf of the poet’ (Scholz, 1992, p. -

Gestalt Psychology and the Anti-Metaphysical Project of the Aufbau

Science and Experience/ Science of Experience: Gestalt Psychology and the Anti-Metaphysical Project of the Aufbau Uljana Feest Technische Universität Berlin This paper investigates the way in which Rudolf Carnap drew on Gestalt psychological notions when deªning the basic elements of his constitutional system. I argue that while Carnap’s conceptualization of basic experience was compatible with ideas articulated by members of the Berlin/Frankfurt school of Gestalt psychology, his formal analysis of the relationship between two ba- sic experiences (“recollection of similarity”) was not. This is consistent, given that Carnap’s aim was to provide a uniªed reconstruction of scientiªc knowl- edge, as opposed to the mental processes by which we gain knowledge about the world. It is this last point that put him in marked contrast to some of the older epistemological literature, which he cited when pointing to the complex character of basic experience. While this literature had the explicit goal of overcoming metaphysical presuppositions by means of an analysis of conscious- ness, Carnap viewed these attempts as still carrying metaphysical baggage. By choosing the autopsychological basis, he expressed his intellectual depth to their antimetaphysical impetus. By insisting on the metaphysical neutrality of his system, he emphasized that he was carrying out a project in which they had not succeeded. 1. Introduction In his 1928 book, Der Logische Aufbau der Welt, Rudolf Carnap presented what he called a “constructional system” (Carnap 1967). The aim of this system was to demonstrate that all of our scientiªc concepts are logically derivable from more “basic” concepts in a hierarchical fashion.