Review Essay: Lullaby for Broadway?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dstprogram-Ticktickboom

SCOTTSDALE DESERT STAGES THEATRE PRESENTS May 7 – 16, 2021 DESERT STAGES THEATRE SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA PRESENTS TICK, TICK...BOOM! Book, Music and Lyrics by Jonathan Larson David Auburn, Script Consultant Vocal Arrangements and Orchestrations by Stephen Oremus TICK, TICK...BOOM! was originally produced off-Broadway in June, 2001 by Victoria Leacock, Robyn Goodman, Dede Harris, Lorie Cowen Levy, Beth Smith Co-Directed by Mark and Lynzee 4man TICK TICK BOOM! is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com WELCOME TO DST Welcome to Desert Stages Theatre, and thank you for joining us at this performance of Jonathan Larson’s TICK, TICK...BOOM! The talented casts that will perform in this show over the next two weekends include some DST “regulars” - familiar faces that you have seen here before - as well as actors who are brand new to the DST stage. Thank you to co- directors Mark and Lynzee 4man who were the natural choices to co- direct (and music direct and choreograph) a rock musical that represents our first teen/young adult production in more than a year. They have worked tirelessly with an extremely skilled team of actors, designers, and crew members to bring you this beautiful show, and everyone involved has enjoyed the process very much. We continue our COVID-19 safety protocols and enhanced cleaning measures to keep you and our actors safe. In return, we ask that you kindly wear your mask the entire time you are in the theatre, and stay in your assigned seat. -

Jonathan Larson

Famous New Yorker Jonathan Larson As a playwright, Jonathan Larson could not have written a more dramatic climax than the real, tragic climax of his own story, one of the greatest success stories in modern American theater history. Larson was born in White Plains, Westchester County, on February 4, 1960. He sang in his school choir, played tuba in the band, and was a lead actor in his high school theater company. With a scholarship to Adelphi University, he learned musical composition. After earning a Fine Arts degree, Larson had to wait tables, like many a struggling artist, to pay his share of the rent in a poor New York City apartment while honing his craft. In the 1980s and 1990s, Larson worked in nearly every entertainment medium possible. He won early recognition for co-writing the award-winning cabaret show Saved!, but his rock opera Superbia, inspired by The original Broadway Rent poster George Orwell’s novel 1984, was never fully staged in Larson’s lifetime. Scaling down his ambitions, he performed a one-man show called tick, tick … BOOM! in small “Off -Broadway” theaters. In between major projects, Larson composed music for children’s TV shows, videotapes and storybook cassette tapes. In 1989, playwright Billy Aronson invited Larson to compose the music for a rock opera inspired by La Bohème, a classical opera about hard-living struggling artists in 19th century Paris. Aronson wanted to tell a similar story in modern New York City. His idea literally struck Larson close to home. Drawing on his experiences as a struggling musician, as well as many friends’ struggles with the AIDS virus, Larson wanted to do all the writing himself. -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

Rodgers & Hammerstein's

2015/16 Season Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Rodgers & Hammerstein’s THE KING AND I Music by RICHARD RODGERSBook and Lyrics by OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN II Based on “Anna and the King of Siam” by Margaret LandonOriginal Orchestrations by Robert Russell Bennett Original Dance Arrangements by Trude RittmannOriginal Choreography by Jerome Robbins LYRIC OPERA OF CHICAGO Table of Contents MARIE-NOËLLE ROBERT / THÉÂTRE DU CHÂTELET IN THIS ISSUE The King and I – pp. 25-41 6 From the President 14 Voyage Of Discovery: : 45 Lyric Unlimited/Education Corps and the General Director Lyric’s 2016-17 Season 46 Aria Society 8 Board of Directors 23 Tonight’s Performance 55 Breaking New Ground/ 25 Cast 10 Women’s Board/Guild Board/ Look to the Future Chapters’ Executive Board/ 26 Musical Numbers/Orchestra 57 Major Contributors – Special Ryan Opera Center Board 27 Artist Profiles Events and Project Support 12 Administration/Administrative 37 A Glorious Partnership 58 Ryan Opera Center Staff/Production and 40 A Talk with the Director Technical Staff 42 Just for Kids 59 Ryan Opera Center Contributors 60 Lyric Unlimited Contributors LYRIC 2016-17 SEASON PREVIEW pp. 16-22 61 Planned Giving: The Overture Society 63 Annual Corporate Support 64 Matching Gifts, Special Thanks and Acknowledgements 65 Annual Individual and MARIE-NOËLLE ROBERT/THÉÂTRE DU CHÂTELET Foundation Support 71 Commemorative Gifts 72 Facilities and Services/Theater Staff On the cover: Paolo Montalban as the King and Kate Baldwin as Anna, photographed by Todd Rosenberg. 2 LYRIC OPERA OF CHICAGO Since 1991 www.performancemedia.us | 847-770-4620 3453 Commercial Avenue, Northbrook, IL 60062 Gail McGrath Publisher & President Sheldon Levin Publisher & Director of Finance A. -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

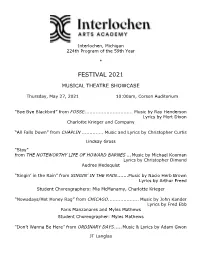

PDF Program Download

Interlochen, Michigan 224th Program of the 59th Year * FESTIVAL 2021 MUSICAL THEATRE SHOWCASE Thursday, May 27, 2021 10:00am, Corson Auditorium “Bye Bye Blackbird” from FOSSE ............................... Music by Ray Henderson Lyrics by Mort Dixon Charlotte Krieger and Company “All Falls Down” from CHAPLIN .............. Music and Lyrics by Christopher Curtis Lindsay Gross “Stay” from THE NOTEWORTHY LIFE OF HOWARD BARNES ... Music by Michael Kooman Lyrics by Christopher Dimond Audree Hedequist “Singin’ in the Rain” from SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN ....... Music by Nacio Herb Brown Lyrics by Arthur Freed Student Choreographers: Mia McManamy, Charlotte Krieger “Nowadays/Hot Honey Rag” from CHICAGO .................... Music by John Kander Lyrics by Fred Ebb Paris Manzanares and Myles Mathews Student Choreographer: Myles Mathews “Don’t Wanna Be Here” from ORDINARY DAYS ..... Music & Lyrics by Adam Gwon JT Langlas “No One Else” from NATASHA, PIERRE AND THE GREAT COMET OF 1812 ......... Music and Lyrics by Dave Malloy Mia McManamy “Run, Freedom, Run” from URINETOWN ...................... Music by Mark Hollmann Lyrics by Mark Hollmann and Greg Kotis Scout Carter and Company “Forget About the Boy” from THOROUGHLY MODERN MILLIE ........................... Music by Jeanine Tesori Lyrics by Dick Scanlan Hannah Bank and Company Student Choreographer: Nicole Pellegrin “She Used to Be Mine” from WAITRESS ........ Music and Lyrics by Sara Bareilles Caroline Bowers “Change” from A NEW BRAIN ......................... Music and Lyrics by William Finn Shea Grande “We Both Reached for the Gun” from CHICAGO .............. Music by John Kander Lyrics by Fred Ebb Theo Gyra and Company Student Choreographer: Myles Mathews “Love is an Open Door” from FROZEN ............ Music & Lyrics by Kristen Anderson-Lopez & Robert Lopez Charlotte Krieger and Daniel Rosales “Being Alive” from COMPANY ............... -

News Release

News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACT: Ben Randle, Artistic Associate & Publicist ~ 415.694.6156 ~ [email protected] Pictures and Press Kit: nctcsf.org/press HARBOR BY TONY® AWARD-NOMINEE CHAD BEGUELIN MAKES WEST COAST PREMIERE AT NCTC Acclaimed new comedy exploring uncharted waters of the shifting meaning of family to be directed by Founder & Artistic Director Ed Decker January 23 – March 1, 2015 San Francisco, CA (December 12, 2014) — In January, New Conservatory Theatre Center presents the West Coast Premiere of the sharp and timely new comedy, Harbor by Chad Beguelin, directed by NCTC Founder & Artistic Director Ed Decker. Kevin’s seemingly perfect world hits troubled waters in this "wickedly funny" play (Variety) when his ne’er-do-well sister, Donna and her teenage daughter show up unexpectedly at the Sag Harbor home he shares with his husband, Ted. This sharp and timely comedy sails through the riptides of family and the unpredictability of the lives we lead. Starring at Ted is former NCTC Conservatory Director, Andrew Nance, last seen at NCTC in an acclaimed performance in Del Shores’ Yellow, last season. Harbor runs January 23 – March 1, 2015 in NCTC’s intimate Walker Theater. Opening Night is Saturday, January 31, 2015 at 8pm. Tickets are $25 - $45 and available at nctcsf.org or by calling (415) 861-8972. Harbor premiered at Westport Playhouse, followed by a New York production at Primary Stages. Variety raves Harbor is “witty and tender” and adds, “The characters in Chad Beguelin’s comedy-drama are hopelessly – and sometimes hysterically – adrift as they seek safe havens in relationships, family, and career. -

Queering William Finn's a New Brain

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2019 Trouble in His Brain: Queering William FNicihnolnas 'Ksri satof eNr Reichward sBonrain Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS “TROUBLE IN HIS BRAIN”: QUEERING WILLIAM FINN’S A NEW BRAIN By NICHOLAS KRISTOFER RICHARDSON A Thesis submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2019 © 2019 Nicholas Kristofer Richardson Nicholas Kristofer Richardson defended this thesis on April 16, 2019. The members of the supervisory committee were: Aaron C. Thomas Professor Directing Thesis Mary Karen Dahl Committee Member Chari Arespacochaga Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have so much for which to be thankful and I am indebted to a great number of people. I will try my best to limit this section to those who helped me specifically with this thesis and these past two years of graduate school. First, I offer heartfelt thanks to my most admirable chair, Dr. Aaron C. Thomas. Thank you for guiding me through this thesis regardless of my many insecurities. Thank you for demanding rigor from me and my work. Thank you for your patience. Thank you for your faith in me. It’s been a pleasure to learn from you and work with you. -

The Creation and Development of Rent by Jonathan Larson

ABSTRACT Title of Document: “OVER THE MOON”: THE CREATION AND DEVELOPMENT OF RENT BY JONATHAN LARSON Elizabeth Titrington, Master of Arts, 2007 Directed By: Professor Richard King Chair, Department of Musicology Despite its critical acclaim and commercial success , the hit musical Rent by Jonathan Larson has received scant attention in academic literature. The story of Rent has been told and retold in the popular media, but a look at Larson’s own drafts, notes, and other personal wri tings adds another important and largely missing voice – Larson’s own. In this study, I use the Jonathan Larson Collection, donated to the Library of Congress in 2004 , to examine this seminal work and composer by tracing Rent ’s development and documenting L arson’s creative process. My analysis of material from the Larson Collection and the interviews of others involved in Rent ’s development reveal s the story of how this unconventional rock musical made it to the stage, highlighting the importance of visio n, but also of revision and collaboration. “OVER THE MOON”: THE CREATION AND DEVELOPMENT OF RENT BY JONATHAN LARSON By Elizabeth Corbin Titrington Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryl and, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2007 Advisory Committee: Professor Richard King , Chair Professor Jonathan Dueck Professor Robert Provine © Copyright by Elizabeth Titrington 2007 Preface Although I cannot claim the status of Rent head – I do not know every word to “La Vie Bohème” by heart or have a website dedicated to the show – I admit to approach ing this project as a fan as well as scho lar. -

Elf the Musical: News Release

NEWS RELEASE For Immediate Release DATE: November 2018 CONTACT: Kori Radloff, [email protected], 402-502-4641 Rose Theater spreads Christmas cheer with Elf the Musical (OMAHA, Nebr.) The Rose Theater is spreading Christmas cheer for all to hear with its upcoming production of Elf the Musical. Based on the cherished 2003 New Line Cinema hit, Elf is holiday fun for everyone. The show opens Nov. 30 and runs through Dec. 23. Elf the Musical follows the story of Buddy (played by Dan Chevalier), an “elf” working at the North Pole who learns he is not an elf at all, but actually a human who crept into Santa’s magic bag of gifts when he was a baby. When he comes to grips with the reality of his enormous size and poor toy-making abilities, he embarks on a journey to New York City to find his birth father and discover his true identity. “When Buddy gets to New York, there is this clash of cultures with his father, Walter Hobbs, and really, with the world. On one hand, we have Buddy, the world’s biggest optimist who believes fundamentally in the goodness of everyone, and he is faced with a world that has grown cynical and jaded, and worst of all – no longer believes in Santa Claus,” says Rose artistic director Matthew Gutschick, who is directing Elf. On the streets of New York City, Buddy encounters individuals who are overwhelmed with the stress of the holidays, who have forgotten the Christmas spirit, and who are filled with negativity. When he arrives at the office of his father, Walter (played by Anthony Clark-Kaczmarek), Buddy finds him ranting to his wife and son about Christmas being a complete annoyance. -

Teacher Resource Guide

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE Rodgers & Hammerstein's The King and I Teacher Resource Guide by Nicole Kempskie MJODPMO!DFOUFS!UIFBUFS BU!UIF!WJWJBO!CFBVNPOU André Bishop Producing Artistic Director Adam Siegel Hattie K. Jutagir Managing Director Executive Director of Development & Planning in association with Ambassador Theatre Group presents RODGERS & HAMMERSTEIN’S Music Book and Lyrics Richard Rodgers Oscar Hammerstein II Based on the novel Anna and the King of Siam by Margaret Landon with Kelli O’Hara Ken Watanabe Ruthie Ann Miles Ashley Park Conrad Ricamora Edward Baker-Duly Jon Viktor Corpuz Murphy Guyer Jake Lucas Paul Nakauchi Marc Oka and Aaron J. Albano Adriana Braganza Amaya Braganza Billy Bustamante LaMae Caparas Hsin-Ping Chang Andrew Cheng Lynn Masako Cheng Olivia Chun Ali Ewoldt Ethan Halford Holder Cole Horibe MaryAnn Hu James Ignacio Misa Iwama Christie Kim Kelvin Moon Loh Sumie Maeda Paul HeeSang Miller Rommel Pierre O’Choa Kristen Faith Oei Autumn Ogawa Yuki Ozeki Stephanie Jae Park Diane Phelan Sam Poon William Poon Brian Rivera Bennyroyce Royon Lainie Sakakura Ann Sanders Ian Saraceni Atsuhisa Shinomiya Michiko Takemasa Kei Tsuruharatani Christopher Vo Rocco Wu XiaoChuan Xie Timothy Yang Sets Costumes Lighting Sound Michael Yeargan Catherine Zuber Donald Holder Scott Lehrer Orchestrations Dance & Incidental Music Arranged by Casting Robert Russell Bennett Trude Rittmann Telsey + Company Abbie Brady-Dalton, CSA Mindich Chair Production Stage Manager Musical Theater Associate Producer General Press Agent Jennifer Rae Moore Ira Weitzman Philip Rinaldi General Manager Production Manager Director of Marketing Jessica Niebanck Paul Smithyman Linda Mason Ross Music Direction Ted Sperling Based on the Choreography Original Choreography by Christopher Gattelli Jerome Robbins Directed by Bartlett Sher Lincoln Center Theater is grateful to the Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater at LCT for their leading support of this production and the Musical Theater Associate Producer’s Chair.