Conference Report THIRD ADVANCED ENCRYPTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improved Rectangle Attacks on SKINNY and CRAFT

Improved Rectangle Attacks on SKINNY and CRAFT Hosein Hadipour1, Nasour Bagheri2 and Ling Song3( ) 1 Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran, [email protected] 2 Electrical Engineering Department, Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, Tehran, Iran, [email protected] 3 Jinan University, Guangzhou, China [email protected] Abstract. The boomerang and rectangle attacks are adaptions of differential crypt- analysis that regard the target cipher E as a composition of two sub-ciphers, i.e., 2 2 E = E1 ◦ E0, to construct a distinguisher for E with probability p q by concatenat- ing two short differential trails for E0 and E1 with probability p and q respectively. According to the previous research, the dependency between these two differential characteristics has a great impact on the probability of boomerang and rectangle distinguishers. Dunkelman et al. proposed the sandwich attack to formalise such dependency that regards E as three parts, i.e., E = E1 ◦ Em ◦ E0, where Em contains the dependency between two differential trails, satisfying some differential propagation with probability r. Accordingly, the entire probability is p2q2r. Recently, Song et al. have proposed a general framework to identify the actual boundaries of Em and systematically evaluate the probability of Em with any number of rounds, and applied their method to accurately evaluate the probabilities of the best SKINNY’s boomerang distinguishers. In this paper, using a more advanced method to search for boomerang distinguishers, we show that the best previous boomerang distinguishers for SKINNY can be significantly improved in terms of probability and number of rounds. -

Lecture Note 8 ATTACKS on CRYPTOSYSTEMS I Sourav Mukhopadhyay

Lecture Note 8 ATTACKS ON CRYPTOSYSTEMS I Sourav Mukhopadhyay Cryptography and Network Security - MA61027 Attacks on Cryptosystems • Up to this point, we have mainly seen how ciphers are implemented. • We have seen how symmetric ciphers such as DES and AES use the idea of substitution and permutation to provide security and also how asymmetric systems such as RSA and Diffie Hellman use other methods. • What we haven’t really looked at are attacks on cryptographic systems. Cryptography and Network Security - MA61027 (Sourav Mukhopadhyay, IIT-KGP, 2010) 1 • An understanding of certain attacks will help you to understand the reasons behind the structure of certain algorithms (such as Rijndael) as they are designed to thwart known attacks. • Although we are not going to exhaust all possible avenues of attack, we will get an idea of how cryptanalysts go about attacking ciphers. Cryptography and Network Security - MA61027 (Sourav Mukhopadhyay, IIT-KGP, 2010) 2 • This section is really split up into two classes of attack: Cryptanalytic attacks and Implementation attacks. • The former tries to attack mathematical weaknesses in the algorithms whereas the latter tries to attack the specific implementation of the cipher (such as a smartcard system). • The following attacks can refer to either of the two classes (all forms of attack assume the attacker knows the encryption algorithm): Cryptography and Network Security - MA61027 (Sourav Mukhopadhyay, IIT-KGP, 2010) 3 – Ciphertext-only attack: In this attack the attacker knows only the ciphertext to be decoded. The attacker will try to find the key or decrypt one or more pieces of ciphertext (only relatively weak algorithms fail to withstand a ciphertext-only attack). -

Hash Functions and the (Amplified) Boomerang Attack

Hash Functions and the (Amplified) Boomerang Attack Antoine Joux1,3 and Thomas Peyrin2,3 1 DGA 2 France T´el´ecomR&D [email protected] 3 Universit´ede Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines [email protected] Abstract. Since Crypto 2004, hash functions have been the target of many at- tacks which showed that several well-known functions such as SHA-0 or MD5 can no longer be considered secure collision free hash functions. These attacks use classical cryptographic techniques from block cipher analysis such as differential cryptanal- ysis together with some specific methods. Among those, we can cite the neutral bits of Biham and Chen or the message modification techniques of Wang et al. In this paper, we show that another tool of block cipher analysis, the boomerang attack, can also be used in this context. In particular, we show that using this boomerang attack as a neutral bits tool, it becomes possible to lower the complexity of the attacks on SHA-1. Key words: hash functions, boomerang attack, SHA-1. 1 Introduction The most famous design principle for dedicated hash functions is indisputably the MD-SHA family, firstly introduced by R. Rivest with MD4 [16] in 1990 and its improved version MD5 [15] in 1991. Two years after, the NIST publishes [12] a very similar hash function, SHA-0, that will be patched [13] in 1995 to give birth to SHA-1. This family is still very active, as NIST recently proposed [14] a 256-bit new version SHA-256 in order to anticipate the potential cryptanalysis results and also to increase its security with regard to the fast growth of the computation power. -

Boomerang Analysis Method Based on Block Cipher

International Journal of Security and Its Application Vol.11, No.1 (2017), pp.165-178 http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijsia.2017.11.1.14 Boomerang Analysis Method Based on Block Cipher Fan Aiwan and Yang Zhaofeng Computer School, Pingdingshan University, Pingdingshan, 467002 Henan province, China { Fan Aiwan} [email protected] Abstract This paper fused together the related key analysis and differential analysis and did multiple rounds of attack analysis for the DES block cipher. On the basis of deep analysis of Boomerang algorithm principle, combined with the characteristics of the key arrangement of the DES block cipher, the 8 round DES attack experiment and the 9 round DES attack experiment were designed based on the Boomerang algorithm. The experimental results show that, after the design of this paper, the value of calculation complexity of DES block cipher is only 240 and the analysis performance is greatly improved by the method of Boomerang attack. Keywords: block cipher, DES, Boomerang, Computational complexity 1. Introduction With the advent of the information society, especially the extensive application of the Internet to break the traditional limitations of time and space, which brings great convenience to people. However, at the same time, a large amount of sensitive information is transmitted through the channel or computer network, especially the rapid development of e-commerce and e-government, more and more personal information such as bank accounts require strict confidentiality, how to guarantee the security of information is particularly important [1-2]. The essence of information security is to protect the information system or the information resources in the information network from various types of threats, interference and destruction, that is, to ensure the security of information [3]. -

Report on the AES Candidates

Rep ort on the AES Candidates 1 2 1 3 Olivier Baudron , Henri Gilb ert , Louis Granb oulan , Helena Handschuh , 4 1 5 1 Antoine Joux , Phong Nguyen ,Fabrice Noilhan ,David Pointcheval , 1 1 1 1 Thomas Pornin , Guillaume Poupard , Jacques Stern , and Serge Vaudenay 1 Ecole Normale Sup erieure { CNRS 2 France Telecom 3 Gemplus { ENST 4 SCSSI 5 Universit e d'Orsay { LRI Contact e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This do cument rep orts the activities of the AES working group organized at the Ecole Normale Sup erieure. Several candidates are evaluated. In particular we outline some weaknesses in the designs of some candidates. We mainly discuss selection criteria b etween the can- didates, and make case-by-case comments. We nally recommend the selection of Mars, RC6, Serp ent, ... and DFC. As the rep ort is b eing nalized, we also added some new preliminary cryptanalysis on RC6 and Crypton in the App endix which are not considered in the main b o dy of the rep ort. Designing the encryption standard of the rst twentyyears of the twenty rst century is a challenging task: we need to predict p ossible future technologies, and wehavetotake unknown future attacks in account. Following the AES pro cess initiated by NIST, we organized an op en working group at the Ecole Normale Sup erieure. This group met two hours a week to review the AES candidates. The present do cument rep orts its results. Another task of this group was to up date the DFC candidate submitted by CNRS [16, 17] and to answer questions which had b een omitted in previous 1 rep orts on DFC. -

The Long Road to the Advanced Encryption Standard

The Long Road to the Advanced Encryption Standard Jean-Luc Cooke CertainKey Inc. [email protected], http://www.certainkey.com/˜jlcooke Abstract 1 Introduction This paper will start with a brief background of the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) process, lessons learned from the Data Encryp- tion Standard (DES), other U.S. government Two decades ago the state-of-the-art in cryptographic publications and the fifteen first the private sector cryptography was—we round candidate algorithms. The focus of the know now—far behind the public sector. presentation will lie in presenting the general Don Coppersmith’s knowledge of the Data design of the five final candidate algorithms, Encryption Standard’s (DES) resilience to and the specifics of the AES and how it dif- the then unknown Differential Cryptanaly- fers from the Rijndael design. A presentation sis (DC), the design principles used in the on the AES modes of operation and Secure Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA) in Digital Hash Algorithm (SHA) family of algorithms Signature Standard (DSS) being case and will follow and will include discussion about point[NISTDSS][NISTDES][DC][NISTSHA1]. how it is directly implicated by AES develop- ments. The selection and design of the DES was shrouded in controversy and suspicion. This very controversy has lead to a fantastic acceler- Intended Audience ation in private sector cryptographic advance- ment. So intrigued by the NSA’s modifica- tions to the Lucifer algorithm, researchers— This paper was written as a supplement to a academic and industry alike—powerful tools presentation at the Ottawa International Linux in assessing block cipher strength were devel- Symposium. -

Mars Pathfinder

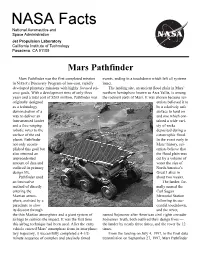

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mars Pathfinder Mars Pathfinder was the first completed mission events, ending in a touchdown which left all systems in NASAs Discovery Program of low-cost, rapidly intact. developed planetary missions with highly focused sci- The landing site, an ancient flood plain in Mars ence goals. With a development time of only three northern hemisphere known as Ares Vallis, is among years and a total cost of $265 million, Pathfinder was the rockiest parts of Mars. It was chosen because sci- originally designed entists believed it to as a technology be a relatively safe demonstration of a surface to land on way to deliver an and one which con- instrumented lander tained a wide vari- and a free-ranging ety of rocks robotic rover to the deposited during a surface of the red catastrophic flood. planet. Pathfinder In the event early in not only accom- Mars history, sci- plished this goal but entists believe that also returned an the flood plain was unprecedented cut by a volume of amount of data and water the size of outlived its primary North Americas design life. Great Lakes in Pathfinder used about two weeks. an innovative The lander, for- method of directly mally named the entering the Carl Sagan Martian atmos- Memorial Station phere, assisted by a following its suc- parachute to slow cessful touchdown, its descent through and the rover, the thin Martian atmosphere and a giant system of named Sojourner after American civil rights crusader airbags to cushion the impact. -

Applied Cryptography and Data Security

Lecture Notes APPLIED CRYPTOGRAPHY AND DATA SECURITY (version 2.5 | January 2005) Prof. Christof Paar Chair for Communication Security Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Sciences Ruhr-Universit¨at Bochum Germany www.crypto.rub.de Table of Contents 1 Introduction to Cryptography and Data Security 2 1.1 Literature Recommendations . 3 1.2 Overview on the Field of Cryptology . 4 1.3 Symmetric Cryptosystems . 5 1.3.1 Basics . 5 1.3.2 A Motivating Example: The Substitution Cipher . 7 1.3.3 How Many Key Bits Are Enough? . 9 1.4 Cryptanalysis . 10 1.4.1 Rules of the Game . 10 1.4.2 Attacks against Crypto Algorithms . 11 1.5 Some Number Theory . 12 1.6 Simple Blockciphers . 17 1.6.1 Shift Cipher . 18 1.6.2 Affine Cipher . 20 1.7 Lessons Learned | Introduction . 21 2 Stream Ciphers 22 2.1 Introduction . 22 2.2 Some Remarks on Random Number Generators . 26 2.3 General Thoughts on Security, One-Time Pad and Practical Stream Ciphers 27 2.4 Synchronous Stream Ciphers . 31 i 2.4.1 Linear Feedback Shift Registers (LFSR) . 31 2.4.2 Clock Controlled Shift Registers . 34 2.5 Known Plaintext Attack Against Single LFSRs . 35 2.6 Lessons Learned | Stream Ciphers . 37 3 Data Encryption Standard (DES) 38 3.1 Confusion and Diffusion . 38 3.2 Introduction to DES . 40 3.2.1 Overview . 41 3.2.2 Permutations . 42 3.2.3 Core Iteration / f-Function . 43 3.2.4 Key Schedule . 45 3.3 Decryption . 47 3.4 Implementation . 50 3.4.1 Hardware . -

Identifying Open Research Problems in Cryptography by Surveying Cryptographic Functions and Operations 1

International Journal of Grid and Distributed Computing Vol. 10, No. 11 (2017), pp.79-98 http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijgdc.2017.10.11.08 Identifying Open Research Problems in Cryptography by Surveying Cryptographic Functions and Operations 1 Rahul Saha1, G. Geetha2, Gulshan Kumar3 and Hye-Jim Kim4 1,3School of Computer Science and Engineering, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India 2Division of Research and Development, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India 4Business Administration Research Institute, Sungshin W. University, 2 Bomun-ro 34da gil, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea Abstract Cryptography has always been a core component of security domain. Different security services such as confidentiality, integrity, availability, authentication, non-repudiation and access control, are provided by a number of cryptographic algorithms including block ciphers, stream ciphers and hash functions. Though the algorithms are public and cryptographic strength depends on the usage of the keys, the ciphertext analysis using different functions and operations used in the algorithms can lead to the path of revealing a key completely or partially. It is hard to find any survey till date which identifies different operations and functions used in cryptography. In this paper, we have categorized our survey of cryptographic functions and operations in the algorithms in three categories: block ciphers, stream ciphers and cryptanalysis attacks which are executable in different parts of the algorithms. This survey will help the budding researchers in the society of crypto for identifying different operations and functions in cryptographic algorithms. Keywords: cryptography; block; stream; cipher; plaintext; ciphertext; functions; research problems 1. Introduction Cryptography [1] in the previous time was analogous to encryption where the main task was to convert the readable message to an unreadable format. -

Applications of Search Techniques to Cryptanalysis and the Construction of Cipher Components. James David Mclaughlin Submitted F

Applications of search techniques to cryptanalysis and the construction of cipher components. James David McLaughlin Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of York Department of Computer Science September 2012 2 Abstract In this dissertation, we investigate the ways in which search techniques, and in particular metaheuristic search techniques, can be used in cryptology. We address the design of simple cryptographic components (Boolean functions), before moving on to more complex entities (S-boxes). The emphasis then shifts from the construction of cryptographic arte- facts to the related area of cryptanalysis, in which we first derive non-linear approximations to S-boxes more powerful than the existing linear approximations, and then exploit these in cryptanalytic attacks against the ciphers DES and Serpent. Contents 1 Introduction. 11 1.1 The Structure of this Thesis . 12 2 A brief history of cryptography and cryptanalysis. 14 3 Literature review 20 3.1 Information on various types of block cipher, and a brief description of the Data Encryption Standard. 20 3.1.1 Feistel ciphers . 21 3.1.2 Other types of block cipher . 23 3.1.3 Confusion and diffusion . 24 3.2 Linear cryptanalysis. 26 3.2.1 The attack. 27 3.3 Differential cryptanalysis. 35 3.3.1 The attack. 39 3.3.2 Variants of the differential cryptanalytic attack . 44 3.4 Stream ciphers based on linear feedback shift registers . 48 3.5 A brief introduction to metaheuristics . 52 3.5.1 Hill-climbing . 55 3.5.2 Simulated annealing . 57 3.5.3 Memetic algorithms . 58 3.5.4 Ant algorithms . -

MARS and the AES Selection Criteria IBM MARS Team May 15, 2000

MARS and the AES Selection Criteria IBM MARS Team May 15, 2000 Abstract As the AES selection process enters its final days, it sometimes seems that the discussion has been reduced to a “beauty contest”, with various irrelevant or red herring issues presented as the differentiating factors between the five finalists. In this note, we discuss the criteria that should (or should not) serve as the basis for selecting an AES winner, and we compare MARS to the other finalists based on these criteria. Also, we examine several of these “beauty contest” issues that were raised, and demonstrate that when subjected to closer scrutiny they turn out to be meaningless. 1 Security and Robustness Although everyone seems to agree that security should be the main criterion for selection, what different people see as the implications of this statement vary widely. It is generally agreed that barring a substantial breakthrough in cryptanalysis, all the finalists are secure. Therefore, some would argue that we should view all ciphers as secure and concentrate on performance and flexibility issues as the selection criteria. This argument is flawed and we strongly disagree with it. With two substantial cryptanalytic breakthroughs in the last ten years (differential and linear cryptanalysis), betting “The Store” (i.e., the security of the AES) on the assumption that no further cryptanalytic breakthroughs will occur, is risky and possibly even dangerous. We postulate that the main criterion for the choice of an AES winner is and should be robustness against future advances in cryptanalysis. With 128 bit blocks and key lengths up to 256 bits, there is no technological reason why the AES cannot withstand brute force key exhaustion attacks for a very long time (25 years, 50 years, perhaps longer). -

Encrypting Volumes Chapter

61417_CH09_Smith.fm Page 383 Tuesday, April 26, 2011 11:25 AM © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION ENCRYPTING VOLUMES CHAPTER © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR 9SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOTABOUT FOR SALE THIS ORCHAPTER DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION In this chapter, we look at the problem of protecting an entire storage device, as opposed to protecting individual files. We look at the following: © Jones & Bartlett •Learning,Risks and policyLLC alternatives for protecting© Jones drive contents & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR• DISTRIBUTIONBlock ciphers that achieve high securityNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION • Block cipher encryption modes • Hardware for volume encryption • Software for volume encryption © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC 9.1 SecuringNOT FORa Volume SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION When we examined file systems in Section 5.1, Bob and Tina suspected that their survey report was leaked through file scavenging: Someone looked at the “hidden” places on © Jonesthe hard & Bartlettdrive. We canLearning, avoid such LLC attacks and protect everything© Jones on the hard& Bartlett drive, Learning, LLC NOTincluding FOR SALE the boot OR blocks, DISTRIBUTION directory entries, and free space, if weNOT encrypt FOR the SALE entire driveOR DISTRIBUTION volume. Note how we use the word volume here: It refers to a block of drive storage that con- tains its own file system. It may be an entire hard drive, a single drive partition, a remov- able USB drive, or any other mass storage device.