Submission to the Inquiry Into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations from the Who Am I? Project1 September 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Soil by Maxine Beneba Clarke HACHETTE

2015 STELLA PRIZE SHORTLISTED TITLE Foreign Soil by Maxine Beneba Clarke HACHETTE ‘Wondrous as she seemed, Shu Yi wasn’t a problem I wanted to take on. Besides, with her arrival my own life had become easier: Melinda and the others hadn’t come looking for me in months. At home, my thankful mother had finally taken the plastic undersheet off my bed.’ Maxine Beneba Clarke, Foreign Soil INTRODUCTION TO THE TEXT suitable for study. A short synopsis and series of This collection of short stories won the Victorian reading questions are allocated for each story, along Premier’s Award for an Unpublished Manuscript in with any themes that are not included in the general 2013, and was subsequently published by Hachette list of the book’s themes below. Following this Australia. It went on to be critically recognised and breakdown are activities that can be applied to the appear on the shortlists for numerous awards. book more broadly. Like all of Maxine Beneba Clarke’s work, this ABOUT THE AUTHOR collection reflects an awareness of voices that are often pushed to the fringes of society, and frequently MAXINE BENEBA CLARKE is speaks to the experiences of immigrants, refugees and an Australian writer and slam single mothers, in addition to lesbian, gay, bisexual, poetry champion of Afro-Caribbean transgender and intersex people. In Foreign Soil, descent. She is the author of the Clarke captures the anger, hope, despair, desperation, poetry collections Gil Scott Heron is strength and desire felt by members of these groups, on Parole (Picaro Press, 2009) and Nothing Here Needs and many others. -

Not the Only Word

REVIEWS Not the Only Word Kenneally, Christine. 2007. The First Word: The Search for the Origins of Language. New York: Penguin Books. By Lyle Jenkins Christine Kenneally’s The First Word is a review of work in the area of language evolution intended as an introductory overview for the general reader and, as such, is a valuable resource for pointers to work in progress on a wide range of evolutionary topics; these include primate calls, birdsong, categorical perception, gene research, computer simulation studies, to name a few. This is the subject of the second and third parts of the book. These parts contain the most valuable information on language evolution research. However, the first part of the book is devoted to interviews with Noam Chomsky, Sue Savage–Rumbaugh, Stephen Pinker and Paul Bloom, and Philip Lieberman. Here the stage is set for a kind of ‘linguistics wars’ on language evolution, with Chomsky on one side of a ‘debate’ and just about everybody else on the other side. This is the least convincing part of the book, as we will see. According to Kenneally, the study of the evolution of language can be divided into several phases — one starting in 1866, when “the Société de Linguistique of Paris declared a moratorium on the topic” (p.7), and another phase when “the official ban developed fairly seamlessly into a virtual ban” (p.79) which was maintained, it is claimed, until the publication of a paper by Pinker and Bloom around 1990 (but see below). The “virtual ban” on the study of evolution of language seems to be ascribed by Kenneally almost solely to Chomsky. -

Communication & Media Studies

COMMUNICATION & MEDIA STUDIES BOOKS FOR COURSES 2011 PENGUIN GROUP (USA) Here is a great selection of Penguin Group (usa)’s Communications & Media Studies titles. Click on the 13-digit ISBN to get more information on each title. n Examination and personal copy forms are available at the back of the catalog. n For personal service, adoption assistance, and complimentary exam copies, sign up for our College Faculty Information Service at www.penguin.com/facinfo 2 COMMUNICaTION & MEDIa STUDIES 2011 CONTENTS Jane McGonigal Mass Communication ................... 3 f REality IS Broken Why Games Make Us Better and Media and Culture .............................4 How They Can Change the World Environment ......................................9 Drawing on positive psychology, cognitive sci- ence, and sociology, Reality Is Broken uncov- Decision-Making ............................... 11 ers how game designers have hit on core truths about what makes us happy and uti- lized these discoveries to astonishing effect in Technology & virtual environments. social media ...................................13 See page 4 Children & Technology ....................15 Journalism ..................................... 16 Food Studies ....................................18 Clay Shirky Government & f CognitivE Surplus Public affairs Reporting ................. 19 Creativity and Generosity Writing for the Media .....................22 in a Connected age Reveals how new technology is changing us from consumers to collaborators, unleashing Radio, TElEvision, a torrent -

Data, the Creation of History and Its Impact on Real Lives

Data, the Creation of History and its Impact on Real Lives Christine Kenneally 14th International Digital Curation Conference 5 February 2019 History and Real Lives • How does history shape us? • How do we know what we know? HOW WHAT WE KNOW SHAPES WHO WE THINK WE ARE A case where even today there is an devastating absence of personal information Plight of orphans seeking information from the government 2012 International Congress on Archives (Brisbane) “The Forgotten Ones” The Monthly, August 2012 “We Saw Nuns Kill Children: The Ghosts of St. Joseph’s Catholic Orphanage” Buzzfeed News, August 2018 Case study: US, Australia Commonalities and Differences • Data curators • Powerful individuals • Justice (transitional, legal) • Journalism, scholarship The critical significance of data curation in a democracy 1. The very great importance of truth to individuals 2. Institutions, even in open, democratic societies, can destroy and rewrite important truths 3. Data curators are frontline guardians to the bedrock of society The world of orphanages • Australia, New Zealand, England, Scotland, Ireland, Canada, US • 19th century, religious, state run • Numbers are hard to quantify • Australia: ½ million children in over 2,000 institutions • US: Over 5 million children in over 3,000 institutions • Numbers peaked in the 1930’s, and declined from the 1960’s • By the 1980’s few remained The world of orphanages • Significant economic and social entities • Used as flagship institutions for charity drives and fund raising, bequests • Recipients of governmental -

Narrative Techniques in Twenty-First Century Popular

NARRATIVE TECHNIQUES IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY POPULAR HOLOCAUST FICTION By Andrea Gapsch April 2021 ________________________ A Thesis presented to The Honors Tutorial College at Ohio University ________________________ In partial fulfillMent of the requireMents for graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English. ________________________ Gapsch 2 Table of Contents Introduction Chapter One CaMp Sisters: Representations of FeMale Friendship and Networks of Support in Rose Under Fire and The Lilac Girls Chapter Two FaMilies and Dual TiMelines: Exploring Representations of Third Generation Holocaust Survivors in The Storyteller and Sarah’s Key Chapter Three The Nonfiction Novel: Comparing The Tattooist of Auschwitz and The Librarian of Auschwitz Conclusion Gapsch 3 Introduction As I began collecting sources for this project in early 2020, Auschwitz celebrated the 75th anniversary of its liberation. Despite more than 75 years of separation from the Holocaust, AMerican readers are still fascinated with the subject. In her book A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction, Ruth Franklin mentions the fear of “Holocaust fatigue” that was discussed in 1980s and 1990s AMerican media, by which she meant the worry that AMericans had heard too about the Holocaust and could not take any more (222). This, Franklin feared, would lead to insensitivity from the general public, even in the face of a massive tragedy such as the Holocaust. After all, in his 1994 book Holocaust Representation: Art within the Limits of History and Ethics, Berel Lang estiMates Holocaust writing to include “tens of thousands” texts, spanning fiction, draMa, MeMoir, poetry, history monographs, and more (35). -

Introduction One Cannot and Must Not Try to Erase the Past Merely Because It Does Not Fit the Present

From THE INVISIBLE HISTORY OF THE HUMAN RACE by Christine Kenneally. Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © Christine Kenneally, 2014. Introduction One cannot and must not try to erase the past merely because it does not fit the present. —Midnight Oil We follow in the steps of our ancestry, and that cannot be broken. — Golda Meir here’s a moment somewhere between the North Pole Tand the South when I look out my window and see the top of the Himalayas. At first the shapes are clouds, but then they resolve into immense snow- covered crags, perfectly still in the cumulus sea. It doesn’t matter how many times I’ve seen them before; I am always surprised. They are proof that I am somewhere very high and very strange. At thirty thousand feet light floods the plane. Ahead the night drapes across the earth. We barrel toward the darkness, and then we tunnel quickly through it. In a few hours, when we land, it will be morning. I call my boyfriend’s attention to the window. “CB! Look!” He won- ders if anyone is over there on the mountains. Perhaps there are a few souls right on the tip. But if so, it’s just us and them and all the other long-distance flying containers up here. We are tracing the outer edge of the human envelope. Below, six billion people inhale. Above, there’s nothing to breathe. It’s at about this point, when I am too tired to read, I have consumed too much wine, and all I can do is stare, that the human condition starts to get to me. -

Appendix: a Brief Review of Scholarship

Appendix: A Brief Review of Scholarship The main subjects of the preceding pages—Donne’s Songs and Sonnets , the mechanisms and repercussions of evolution, the fields of Biology and Cognition it led to, and an allied science of Love—are not always easy to understand. I have tried to be comprehensible and to share my contagious interests; my success can only be judged by my readers. Fortunately for all of us, though, some admirably lucid com- mentators have turned their attentions to explaining Donne, Darwin, and desire, and this guide is presented with the aim of clearing up confusions and prompting further inquiry (full citations are found in the Works Cited.) There are extensive—better said, excessive —bodies of scholarship on every minute subtopic touched on here, enough to make the most diehard Holmesian investigator or grad student despair. Mountains of material have been published on, well, everything, down to gold and alchemy, gossip, particular metaphorical schema such as Donne’s compasses, and so forth. No claims for systematic inclusiveness are advanced here. More specifically, let me note that the previous chap- ters have (relatively) few citations to the history of science, to overhasty first-generation efforts at sociobiological literary criticism, and to the masses of twentieth-century work on Donne’s poems, though many of those pieces are topnotch and sometimes stand, at one remove, behind interpretations that are generally accepted today. Donne criticism may be said to have reached its full-blown matu- rity, and now occupies several shelves in most well-stocked university libraries. To boil it down to a single paragraph: the two most influen- tial opponents of Metaphysical verse were John Dryden and Samuel Johnson. -

COVID-19 Advisory on International Surrogacy Arrangements

July 30, 2020 COVID-19 Advisory On International Surrogacy Arrangements Surrogacy360 has released a COVID-19 advisory on international surrogacy. In addition to the usual risks of cross-border surrogacy arrangements, the pandemic raises additional concerns and heightened risks for all parties involved. The advisory urges avoiding international surrogacy arrangements at this time. Read Surrogacy360's COVID-19 Advisory. WHO Seeking Public Comment on Draft Governance Framework for Human Genome Editing The WHO Expert Advisory Committee on Developing Global Standards for Governance and Oversight of Human Genome Editing has released a draft of their proposed governance framework and is seeking comments from the public through August 19, 2020. CGS encourages you to review the draft governance framework and submit comments to the online questionnaire. Your perspective and contribution are urgently needed in the development of this significant global policy document. CGS Welcomes Quinn Brashares CGS is pleased to introduce our new intern, Quinn Brashares. Quinn is interested in working towards social equity in the realms of genetic engineering, the justice system, and artificial intelligence. He recently graduated from the University of Miami with a BA in political and environmental science and plans to pursue a law degree in the coming years. Quinn says that CGS represents to him a paramount cause, a place to absorb and deepen knowledge, and a wonderful community of similar minds. Welcome, Quinn! COVID, Data, DNA, and the Future Pete Shanks, Biopolitical Times | 07.20.2020 Enormous and potentially dangerous real-world consequences flow freely from Big Data toward a wide swath of individuals and communities. -

When Genealogy Gets Distorted KRISTIN E

When Genealogy Gets Distorted KRISTIN E. HARLEY ustralian-American journalist and linguist Christine Kenneally’s sec- Aond book is a cutting-edge blend The Invisible History of the Human Race: How of molecular and population genetics, DNA and History Shape Our Identities and Our social science, and artefactual records. Futures. By Christine Kenneally. Viking (Penguin While not a book specifically about Group), New York, 2014. ISBN 9780698176294. pseudoscience, Kenneally’s comprehen- 368 pp. Hardcover, $18.98; U.S. Kindle Edition, sive research demonstrates that, alas, $11.99. wherever science is, ignorance makes inroads. The Invisible History of the Human Race details how genealogy was distorted and misapplied to obscure facts and to oppress people. Genealogy as a pseudoscience is most obvious in Genealogy as a pseudo- the “racial science” of the Third Reich, Denialism there was also—what which required all good Germans to science is most obvious in Kenneally calls “silence passed down.” demonstrate no Jewish inbreeding the “racial science” of the During the transport of convicts from from the year 1800 on. Inspired by Third Reich, which required Britain to Australia, the British aris- tocracy believed that criminal behavior eugenicist Madison Grant (and not by all good Germans to Charles Darwin), Hitler exterminated was inherited through “defective fam- the “unfit.” For those not condemned, demonstrate no Jewish ilies.” As a result, fearing the convict the Lebensborn and the coldly bureau- inbreeding from the year stain and wanting respectable lives in cratic Reich’s Genealogical Authority 1800 on. Inspired by a land declared a “den of thieves,” the produced anxiety, misery, and shame eugenicist Madison Tasmanians willingly whitewashed that lasted for decades and caused their family stories and invented out- some Germans to shun any research Grant (and not by Charles rageous tales of their “proper” origins into family history as a slippery slope. -

Philosophy Religion& Books for Courses

2 0 1 1 PHILOSOPHY RELIGION& BOOKS FOR COURSES PENGUIN GROUP USA PHILOSOPHY RELIGION& BOOKS FOR COURSES 2011 PHILOSOPHY RELIGION WesteRn philosophy . 3 Religion in todAy’s WoRld . 3 0 ANCIENT . 3 Religion & Science . 31 Plato. 4 Relgion in America . 33 MEDIEVAL . 5 BiBle studies . 3 4 RENAISSANCE & EARLY MODERN (c. 1600–1800) . 6 ChRistiAnity . 3 5 The Penguin History LATER MODERN (c. 1800-1960) . 7 of the Church . 35 CONTEMPORARY . 8 Diarmaid MacCulloch . 37 Ayn Rand. 11 Women in Christianity . 38 eAsteRn philosophy . 1 2 J u d A i s m . 3 9 Sanskrit Classics . 12 B u d d h i s m . 4 0 s o C i A l & p o l i t i C A l His Holiness the Dalai Lama . 40 p h i l o s o p h y . 1 3 Karl Marx. 15 i s l A m . 4 2 Philosophy & the Environment . 17 h i n d u i s m . 4 4 philosophy & sCienCe . 1 8 Penguin India . 44 Charles Darwin . 19 nAtiVe AmeRiCAn . 4 5 philosophy & ARt . 2 2 The Penguin Library of American Indian History . 45 philosophy & Religion in liteRAtuRe . 2 3 A n C i e n t R e l i g i o n Jack Kerouac. 26 & mythology . 4 6 Penguin Great Ideas Series . 29 AnthRopology oF Religion . 4 7 spiRituAlity . 4 8 Complete idiot’s guides . 5 0 R e F e R e n C e . 5 1 i n d e X . 5 2 College FACulty inFo seRViCe . 5 6 eXAminAtion Copy FoRm . -

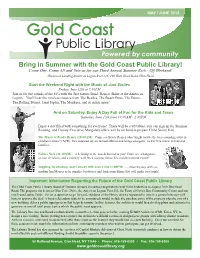

Bring in Summer with the Gold Coast Public Library!

MAY / JUNE 2015 Bring in Summer with the Gold Coast Public Library! Come One, Come All and Join us for our Third Annual Summer Kick - Off Weekend! Glenwood Landing American Legion Post 336, 190 Glen Head Road, Glen Head Start the Weekend Right with the Music of Just Sixties Friday, June 12th at 7:30PM Join us for the sounds of the 60’s with the Just Sixties Band. Rain or Shine at the American Legion. You'll hear the timeless classics from The Beatles, The Beach Boys, The Doors, The Rolling Stones, Janis Joplin, The Monkees, and so much more! And on Saturday, Enjoy A Day Full of Fun for the Kids and Teens Saturday, June 13th from 10:00AM - 2:00PM Enjoy a day fi lled with something for everyone! There will be craft tables, you can sign up for Summer Reading, and County Executive Mangano's offi ce will be on hand to prepare Child Safety Kits. The Music of Brady Rymer (10:00AM) Come see Brady Rymer who "might just be the best-sounding artist in children's music" (NPR). He's released six acclaimed albums and brings energetic, rockin' live music to kids and families. Nature Nick (11:30AM) ... a fi eld trip to the zoo-delivered to you! Come see a kangaroo, an owl or falcon, and a monkey with Nick Jacinto, News 12's resident animal expert! Juggling, Beatboxing, and Comedy with Jester Jim (1:00PM) ..... close the day with co- median Jim Maurer as he juggles, beatboxes and lands punchlines that will make you laugh! Important Information Regarding the Future of the Gold Coast Public Library The Gold Coast Public Library Board of Trustees remains in contract negotiations with Halm Industries to acquire 180 Glen Head Road. -

New Books New Books for Social Studies Course Use & Adoption Fall 2014 / Spring 2015

PENGUIN GROUP (USA) new books new books for social studies course use & adoption fall 2014 / spring 2015 • • • I’m Therese Neumann, Midwest College Field Sales Representative You can contact me with any questions or requests at [email protected] • • • PENGUIN GROUP (USA) new books for course use & adoption fall 2014 / spring 2015 POLITICAL SCIENCE Capital: The Eruption of Delhi The Investigator Rana Dasgupta • 978-0-14-312699-7 • $18.00 • Terry Lenzner • 978-0-14-218135-5 • $17.00 • May 2015 • Penguin • In a series of meetings Oct 2014 • Plume • In his wide-ranging career Believer: My Forty Years in Politics with a wide swath of the population of India’s memoir, Lenzner speaks publicly about his David Axelrod • 978-1-59420-587-3 • $29.95 • capital city—from Delhi’s forgotten poor to its high-profile investigations and world-famous Feb 2015 • Penguin Press • The strategist who rich tech entrepreneurs—Commonwealth clients for the first time. • “An absorbing masterminded Obama’s historic election Writers’ Prize winner Rana Dasgupta presents account of dedicated public service, cunning campaigns opens up about his years as a young an intimate portrait of the people living, intrigue and Beltway politics.”—Monroe E. journalist, political consultant, and ultimately suffering, and striving for more in this city of Price, Director, Center for Global senior adviser to the president. In frankly extremes, as well as a glimpse of our shared Communications Studies Annenberg School sharing his life and work over the decades, global future. for Communication Axelrod ultimately traces the continuing evolution of the Democratic Party and the Double Down: Game Change 2012 The Penguin Book of Modern Speeches country at large.