Changing Attitudes? a Comparative Study of the Role of Politics and Political Discourse in the Development of Attitudes Towards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L E S B I a N / G

LESBIAN/GAY L AW JanuaryN 2012 O T E S 03 11th Circuit 10 Maine Supreme 17 New Jersey Transgender Ruling Judicial Court Superior Court Equal Protection Workplace Gestational Discrimination Surrogacy 05 Obama Administration 11 Florida Court 20 California Court Global LGBT Rights of Appeals of Appeal Parental Rights Non-Adoptive 06 11th Circuit First Same-Sex Co-Parents Amendment Ruling 14 California Anti-Gay Appellate Court 21 Texas U.S. Distict Counseling Non-Consensual Court Ruling Oral Copulation High School 09 6th Circuit “Outing” Case Lawrence- 16 Connecticut Based Challenge Appellate Ruling Incest Conviction Loss of Consortium © Lesbian/Gay Law Notes & the Lesbian/Gay Law Notes Podcast are Publications of the LeGaL Foundation. LESBIAN/GAY DEPARTMENTS 22 Federal Civil Litigation Notes L AW N O T E S 25 Federal Criminal Litigation Editor-in-Chief Notes Prof. Arthur S. Leonard New York Law School 25 State Criminal Litigation 185 W. Broadway Notes New York, NY 10013 (212) 431-2156 | [email protected] 26 State Civil Litigation Notes Contributors 28 Legislative Notes Bryan Johnson, Esq. Brad Snyder, Esq. 30 Law & Society Notes Stephen E. Woods, Esq. Eric Wursthorn, Esq. 33 International Notes New York, NY 36 HIV/AIDS Legal & Policy Kelly Garner Notes NYLS ‘12 37 Publications Noted Art Director Bacilio Mendez II, MLIS Law Notes welcomes contributions. To ex- NYLS ‘14 plore the possibility of being a contributor please contact [email protected]. Circulation Rate Inquiries LeGaL Foundation 799 Broadway Suite 340 New York, NY 10003 THIS MONTHLY PUBLICATION IS EDITED AND (212) 353-9118 | [email protected] CHIEFLY WRIttEN BY PROFESSOR ARTHUR LEONARD OF NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL, Law Notes Archive WITH A STAFF OF VOLUNTEER WRITERS http://www.nyls.edu/jac CONSISTING OF LAWYERS, LAW SCHOOL GRADUATES, AND CURRENT LAW STUDENTS. -

United States V. Windsor and the Future of Civil Unions and Other Marriage Alternatives

Volume 59 Issue 6 Tolle Lege Article 4 9-1-2014 United States v. Windsor and the Future of Civil Unions and Other Marriage Alternatives John G. Culhane Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation John G. Culhane, United States v. Windsor and the Future of Civil Unions and Other Marriage Alternatives, 59 Vill. L. Rev. Tolle Lege 27 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol59/iss6/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Culhane: United States v. Windsor and the Future of Civil Unions and Other VILLANOVA LAW REVIEW ONLINE: TOLLE LEGE CITE: VILL. L. REV. TOLLE LEGE 27 (2013) UNITED STATES v. WINDSOR AND THE FUTURE OF CIVIL UNIONS AND OTHER MARRIAGE ALTERNATIVES JOHN G. CULHANE* HE Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Windsor1 was a T victory for the LGBT rights movement and a vindication of basic principles of dignity and equality. The Court ruled that Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which defined marriage as the union of a man and a woman for purposes of federal law,2 betrayed the Constitution’s promise of liberty, as expressed through the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.3 For Justice Kennedy, who authored the majority opinion, congressional zeal for excluding legitimately married same-sex couples from the federal benefits and responsibilities attendant to marriage could only be explained by animus toward these couples.4 For evidence of such animus, the Court looked no further than the many anti-gay statements that found their way into the Congressional Record and the House Report of DOMA.5 That Congress cut so deeply into the definition of marriage otherwise left to the individual states, just to exclude same-sex couples, was further proof of the true purpose behind DOMA. -

When Marriage Is Too Much: Reviving the Registered Partnership in a Diverse Society Abstract

M ARY C HARLOTTE Y . C ARROLL When Marriage Is Too Much: Reviving the Registered Partnership in a Diverse Society abstract. In the years since same-sex marriage’s legalization, many states have repealed their civil union and domestic partnership laws, creating a marriage-or-nothing binary for couples in search of relationship recognition. This Note seeks to add to the growing call for legal recognition of partnership pluralism by illustrating why marriage is not the right fit—or even a realistic choice—for all couples. It highlights in particular the life-or-death consequences matrimony can bring for those reliant on government healthcare benefits because of a disability or a need for long- term care. Building upon interview data and a survey of state nonmarital partnership policies, it proposes the creation of a customizable marriage alternative: the registered partnership. author. Yale Law School, J.D. 2020; University of Cambridge, M.Phil. approved 2017; Rice University, B.A. 2016. I am grateful first and foremost to Anne Alstott, whose endless support, encouragement, and feedback enabled me to write this Note. I am further indebted to Frederik Swennen and Wilfried Rault for taking the time to speak with me about nonmarital partnerships in France and Belgium and to Kaiponanea T. Matsumura and Michael J. Higdon for invaluable guidance on nonmarital partnerships in the United States. Thanks also to the wonderful editors of the Yale Law Journal’s Notes & Comments Committee, especially Abigail Fisch, for their thoughtful comments; to the First- and Second-Year Editors, for their careful review of my Note; and to the Streicker Fund for Student Research, whose generosity made it possible for me to con- duct the research that informed this project. -

Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race the Opportunity Agenda

Opinion Research & Media Content Analysis Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race The Opportunity Agenda Acknowledgments This research was conducted by Loren Siegel (Executive Summary, What Americans Think about LGBT People, Rights and Issues: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Public Opinion, and Coverage of LGBT Issues in African American Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); Elena Shore, Editor/Latino Media Monitor of New America Media (Coverage of LGBT Issues in Latino Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); and Cheryl Contee, Austen Levihn- Coon, Kelly Rand, Adriana Dakin, and Catherine Saddlemire of Fission Strategy (Online Discourse about LGBT Issues in African American and Latino Communities: An Analysis of Web 2.0 Content). Loren Siegel acted as Editor-at-Large of the report, with assistance from staff of The Opportunity Agenda. Christopher Moore designed the report. The Opportunity Agenda’s research on the intersection of LGBT rights and racial justice is funded by the Arcus Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are those of The Opportunity Agenda. Special thanks to those who contributed to this project, including Sharda Sekaran, Shareeza Bhola, Rashad Robinson, Kenyon Farrow, Juan Battle, Sharon Lettman, Donna Payne, and Urvashi Vaid. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works with social justice groups, leaders, and movements to advance solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and corresponding solutions; uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. -

Final Version

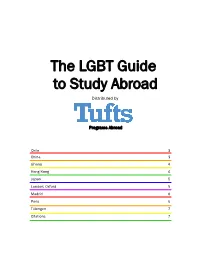

The LGBT Guide to Study Abroad Distributed by Programs Abroad Chile 3 China 3 Ghana 4 Hong Kong 4 Japan 5 London; Oxford 5 Madrid 6 Paris 6 Tübingen 7 Citations 7 Dear Student, The Pew Research Center conducted a world-wide survey between March and May of 2013 on the subject of homo- sexuality. They asked 37,653 participants in 39 countries, “Should society accept homosexuality?” The results, summariZed in this graphic, are revealing. There is a huge variance by region; some countries are extremely divided on the issue. Others have been, and continue to be, widely accepting of homosexuality. This information is relevant not only to residents of these countries, but to travelers and students who will be studying abroad. Students going abroad should be prepared for noted differences in attitudes toward individuals. Before depar- ture, it can be helpful for LGBT students to research cur- rent events pertaining to LGBT rights, general tolerance of LGBT persons, legal protection of LGBT individuals, LGBT organizations and support systems, and norms in the host culture’s dating scene. We hope that the following summaries will provide a starting point for the LGBT student’s exploration of their destination’s culture. If students are in homestay situations, they should consider the implications of coming out to their host family. Students may choose to conceal their sexual orientation to avoid tension in the student-host family relationship. Other times, students have used their time away from their home culture as an opportunity to come out. Some students have even described coming out overseas as a liberating experience, akin to a “second” coming out. -

Criminalising Homosexuality and Understanding the Right to Manifest

Criminalising Homosexuality and Understanding the Right to Manifest Religion Yet, while the Constitution protects the right of people to continue with such beliefs, it does not allow the state to turn these beliefs – even in moderate or gentle versions – into dogma imposed on the whole of society. Contents South African Constitutional Court, 19981 Overview 4 Religion and proportionality 11 Religion and government policy 21 Statements from religious leaders on LGBT matters 25 Conclusion 31 Appendix 32 This is one in a series of notes produced for the Human Dignity Trust on the criminalisation of homosexuality and good governance. Each note in the series discusses a different aspect of policy that is engaged by the continued criminalisation of homosexuality across the globe. The Human Dignity Trust is an organisation made up of international lawyers supporting local partners to uphold human rights and constitutional law in countries where private, consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex is criminalised. We are a registered charity no.1158093 in England & Wales. All our work, whatever country it is in, is strictly not-for-profit. 1 National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality and Another v Minister of Justice and Others [1998] ZACC 15 (Constitutional Court), para. 137. 2 3 Criminalising Homosexuality and Understanding the Right to Manifest Religion Overview 03. The note then examines whether, as a The origin of modern laws that expanding Empire in Asia, Africa and the matter of international human rights law, Pacific. For instance, the Indian Penal Code 01. Consensual sex between adults of the adherence to religious doctrine has any criminalise homosexuality of 1860 made a crime of ‘carnal knowledge same-sex is a crime in 78 jurisdictions.2 bearing on whether the state is permitted to 05. -

How Doma, State Marriage Amendments, and Social Conservatives Undermine Traditional Marriage

TITSHAW [FINAL] (DO NOT DELETE) 10/24/2012 10:28 AM THE REACTIONARY ROAD TO FREE LOVE: HOW DOMA, STATE MARRIAGE AMENDMENTS, AND SOCIAL CONSERVATIVES UNDERMINE TRADITIONAL MARRIAGE Scott Titshaw* Much has been written about the possible effects on different-sex marriage of legally recognizing same-sex marriage. This Article looks at the defense of marriage from a different angle: It shows how rejecting same-sex marriage results in political compromise and the proliferation of “marriage light” alternatives (e.g., civil unions, domestic partnerships or reciprocal beneficiaries) that undermine the unique status of marriage for everyone. After describing the flexibility of marriage as it has evolved over time, the Article focuses on recent state constitutional amendments attempting to stop further development. It categorizes and analyzes the amendments, showing that most allow marriage light experimentation. It also explains why ambiguous marriage amendments should be read narrowly. It contrasts these amendments with foreign constitutional provisions aimed at different-sex marriages, revealing that the American amendments reflect anti-gay animus. But they also reflect fear of change. This Article gives reasons to fear the failure to change. Comparing American and European marriage alternatives reveals that they all have distinct advantages over traditional marriage. The federal Defense of Marriage Act adds even more. Unlike same-sex marriage, these alternatives are attractive to different-sex couples. This may explain why marriage light * Associate Professor at Mercer University School of Law. I’d like to thank Professors Kerry Abrams, Tedd Blumoff, Johanna Bond, Beth Burkstrand-Reid, Patricia A. Cain, Jessica Feinberg, David Hricik, Linda Jellum, Joseph Landau, Joan MacLeod Hemmingway, David Oedel, Jack Sammons, Karen Sneddon, Mark Strasser, Kerri Stone, and Robin F. -

Keeping Bees in the City?

KEEPING BEES IN THE CITY? DISAPPEARING BEES AND THE EXPLOSION OF URBAN AGRICULTURE INSPIRE URBANITES TO KEEP HONEYBEES: WHY CITY LEADERS SHOULD CARE AND WHAT THEY SHOULD DO ABOUT IT Kathryn A. Peters* I. Introduction .......................................................................................... 598 II. The Life of Honeybees ........................................................................ 600 A. Life in the Hive ............................................................................... 600 B. Honeybees in Commercial Agriculture .......................................... 604 C. Honeybees in Urban Agriculture ................................................... 610 III. The Disappearance of the Bees ............................................................ 614 A. Honeybee Health Pre-Colony Collapse ......................................... 615 B. Mad Bee Disease ............................................................................ 616 C. The Emergence of Colony Collapse Disorder ................................ 619 D. Possible Causes of Colony Collapse Disorder ............................... 621 E. Pesticides and Colony Collapse Disorder....................................... 624 F. The Role of Federal Pesticide Regulation ...................................... 628 IV. Keeping Bees in the City? ................................................................... 631 A. Municipal Regulation of Urban Beekeeping ................................. 632 B. Case Studies of Beekeeping Ordinances in U.S. Cities ................ -

Newsletter Issue 16 Summer 2012

OLGA NEWSLETTER ISSUE 16 June-July-August 2012 OLGA Useful contact information Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Trans Association A Community Network SEXUALITY Albion Pub & Cabaret PO Box 458 Scarborough YO11 9EH Telephone: 07929 465044 136 Castle Road, Scarborough Tel: 01723 379068 OLGA Tel: 07929 465 044 Email: [email protected] www.olga.uk.com Email: [email protected] www.olga.uk.com Gay Scarborough Tel: 01723 375 849 Newsletter Issue 16 June-July-August 2012 P0 Box 458, Scarborough YO11 9EH Bacchus Night Club Tel: 01723 373 689 MESMAC Yorkshire. Tel: 01904 620 400 7a Ramshill Road, Scarborough YO11 P0 Box 549, York. Y030 7GX York Lesbian Social Group 18+ Tel: 07963 414434 MENTAL HEALTH Email: [email protected] OLGA’s successes GENERAL ADVICE Crisis Call Tel: 0800 501 254 (telephone support) One or two particular successes care homes, which makes our 01723 384644 (crisis response, resolution and Customer First Tel: 01723 232 323 need to be highlighted. work extremely valuable and home treatment) (Free from landlines. Mobiles - Scarborough Borough Council (General Enquiries) Firstly, our work is being needed. We believe that Peter cost for initial message and Crisis Call will call St. Nicholas Street, Scarborough YO11 2HG researched and will be Tatchell has begun to be you back, which is free) OLGA TeI: 07929 465 044 Summer has arrived, after a published by a senior involved in olgbt care issues. Great. We need his strong Samaritans Tel: 01723 368 888 Email: [email protected] long drawn out wet Spring. So, researcher from Nottingham voice. Samaritan House, 40 Trafalgar Street West, P0 Box 458, Scarborough YO11 9EH we hope our readers can enjoy University, End-of-life and Scarborough YO12 7AS Age UK Scarborough Tel: 01723379058 more outdoor activities and get Palliative Care Department. -

The Challenges of Advancing Equal Rights for LGBT Individuals in an Increasingly Diverse Society: the Case of the French Taubira Law

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Baker Scholar Projects and Creative Work 5-2015 The Challenges of Advancing Equal Rights for LGBT Individuals in an Increasingly Diverse Society: the Case of the French Taubira Law Ashley M. Jakubek University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_bakerschol Recommended Citation Jakubek, Ashley M., "The Challenges of Advancing Equal Rights for LGBT Individuals in an Increasingly Diverse Society: the Case of the French Taubira Law" (2015). Baker Scholar Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_bakerschol/29 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baker Scholar Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Challenges of Advancing Equal Rights for LGBT Individuals in an Increasingly Diverse Society: the Case of the French Taubira Law (Loi n° 2013-404 du 17 mai 2013 ouvrant le mariage aux couples de personnes de même sexe – Mariage Pour Tous) By Ashley Marissa Jakubek A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of: The Chancellor’s Honors Program, Political Science Honors, French Honors, and the Baker Scholars Program at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville May 2015 Advisors: Dr. Sébastien Dubreil and Dr. Anthony Nownes Jakubek 2 Introduction Globalization has brought unprecedented progressive change to society. The world has become significantly more connected with new technologies able to link individuals from across the world almost instantly, and people are more mobile than at any point in history (Blommaert 2010). -

BMJ in the News Is a Weekly Digest of Journal Stories, Plus Any Other News

BMJ in the News is a weekly digest of journal stories, plus any other news about the company that has appeared in the national and a selection of English-speaking international media. Latest highlights (17-23 Sep): ● Launch of BMJ’s new journal General Psychiatry was covered by trade outlet InPublishing ● A study in The BMJ showing a link between a high-gluten diet in pregnancy and child diabetes generated widespread coverage, including the The Guardian, Hindustan Times, and 100+ mentions in UK local newspapers ● Two studies in BMJ Open generated global news headlines this week - high sugar content of most supermarket yogurts and air pollution linked to heightened dementia risk. Coverage included ABC News, CNN, Newsweek, Beijing Bulletin and 200+ mentions in UK local print and broadcast outlets BMJ BMJ to publish international psychiatry journal - InPublishing 19/09/2018 British Journalism Awards for Specialist Media 2018: Winners announced (Gareth Iacobucci winner) InPublishing 20/09/18 The BMJ Analysis: Revisiting the timetable of tuberculosis ‘Latent’ Tuberculosis? It’s Not That Common, Experts Find - New York Times 20/09/2018 Also covered by: Business Standard, The Hindu iMedicalApps: This Week's Top Picks: The BMJ - MedPage Today 21/09/2018 Also covered by: Junkies Tech Research: Association between maternal gluten intake and type 1 diabetes in offspring: national prospective cohort study in Denmark Eating lots of pasta during pregnancy doubles the risk of children getting Type 1 diabetes by -

Divorce Without Marriage

Hastings Law Journal Volume 54 | Issue 3 Article 5 1-2003 Divorce without Marriage: Establishing a Uniform Dissolution Procedure for Domestic Partners through a Comparative Analysis of European and American Domestic Partner Laws Jessica A. Hoogs Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jessica A. Hoogs, Divorce without Marriage: Establishing a Uniform Dissolution Procedure for Domestic Partners through a Comparative Analysis of European and American Domestic Partner Laws, 54 Hastings L.J. 707 (2003). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol54/iss3/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Notes Divorce Without Marriage: Establishing a Uniform Dissolution Procedure for Domestic Partners Through a Comparative Analysis of European and American Domestic Partner Laws by JESSICA A. HoOGS* Introduction No couple in the first throes of love wants to consider the possibility that their "perfect" relationship may someday fall apart. The unfortunate reality is, however, that over forty percent of marriages today end in divorce.' Divorce, while painful, can provide individuals a sense of finality, even accomplishment, at having made it through a difficult emotional, legal and psychological event.2 However, for same-sex couples who are not legally entitled to formalize their relationships through the institution of marriage, the legal procedure of divorce is simply not available. Are couples in same-sex relationships less likely to break up than opposite-sex couples? Although gay couples may feel pressure from the gay community to stay together to show the world that same-sex * J.D.