Preachers in the Service of Bishop John Carroll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Priest/Deacon for Your Wedding

PREPARING FOR CHRISTIAN MARRIAGE Our Lady of the Pillar Catholic Church Renee Fesler 401 S. Lindbergh Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63131 314-993-2280 Fax: 314-993-6462 -------------- Our Lady of the Pillar July, 2017 P. 1 Best wishes on your engagement! Our Lady of the Pillar is pleased to help you as an engaged couple to prepare for the Sacrament of Marriage. Now that you are engaged, here is what you need to do: 1. The Parish Office, 314-993-2280. Thank you for contacting Our Lady of the Pillar for your wedding. 2. Confirming the date for your marriage and the rehearsal. • Contact the Parish Office at least 6 months ahead of time to see if your preferred date is available. 3. Priest/Deacon for your wedding. • If your presider is one of the OLP parish priests/deacon, you will be directed to him. He will assist you with the necessary paper work. • The church is not reserved until the presider is selected and the church fee is received. • If the presider is not a priest/deacon from Our Lady of the Pillar, the applicable forms must be received by the Associate Pastor before the church is reserved. • You will be directed to the Associate Pastor who will assist you in getting the necessary permission and the appropriate forms as needed. • All visiting priests/deacons must submit to the Associate Pastor The Agreement of the Officiating Priest/Deacon. If the visiting priest/deacon is from outside of the St. Louis Archdiocese, he must also submit a Letter of Suitability from his bishop or provincial superior. -

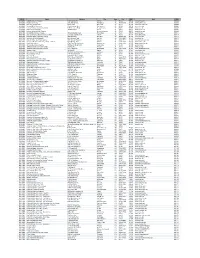

Office of Postsecondary Education Identifier Data

OPEID8 Name Address City State Zip IPED6 Web OPEID6 00100200 Alabama A & M University 4900 Meridian St Normal AL 35762 100654 www.aamu.edu/ 001002 00100300 Faulkner University 5345 Atlanta Hwy Montgomery AL 36109-3378 101189 www.faulkner.edu 001003 00100400 University of Montevallo Station 6001 Montevallo AL 35115 101709 www.montevallo.edu 001004 00100500 Alabama State University 915 S Jackson Street Montgomery AL 36104 100724 www.alasu.edu 001005 00100700 Central Alabama Community College 1675 Cherokee Road Alexander City AL 35010 100760 www.cacc.edu 001007 00100800 Athens State University 300 N Beaty St Athens AL 35611 100812 www.athens.edu 001008 00100900 Auburn University Main Campus Auburn University AL 36849 100858 www.auburn.edu 001009 00101200 Birmingham Southern College 900 Arkadelphia Road Birmingham AL 35254 100937 www.bsc.edu 001012 00101300 John C Calhoun State Community College 6250 U S Highway 31 N Tanner AL 35671 101514 www.calhoun.edu 001013 00101500 Enterprise State Community College 600 Plaza Drive Enterprise AL 36330-1300 101143 www.escc.edu 001015 00101600 University of North Alabama One Harrison Plaza Florence AL 35632-0001 101879 www.una.edu 001016 00101700 Gadsden State Community College 1001 George Wallace Dr Gadsden AL 35902-0227 101240 www.gadsdenstate.edu 001017 00101800 George C Wallace Community College - Dothan 1141 Wallace Drive Dothan AL 36303-9234 101286 www.wallace.edu 001018 00101900 Huntingdon College 1500 East Fairview Avenue Montgomery AL 36106-2148 101435 www.huntingdon.edu 001019 00102000 Jacksonville -

Amhs Plans Virtual Spring-Summer Programs

A Publication of the Abruzzo and Molise Heritage Society of the Washington DC Area May/June 2021 What’s Inside A documentary on celebrated chef and pasta expert Evan Funke (above) will be the subject of the next AMHS film discussion on June 12. Credit: Courtesy of Kitchen Detail 02 President’s Message 03 The Politically Talented AMHS PLANS VIRTUAL D’Alesandro Family, Part II 04 Author Michele Antonelli SPRING-SUMMER PROGRAMS Shares Wisdom from Abruzzo By Nancy DeSanti, 1st Vice President — Programs 05 Grab the Mattarello: ith the timetable for returning to in-person events still uncertain, the AMHS Program Let Battle Commence? Committee has lined up some interesting virtual events which we hope our members and friends will enjoy. 07 Campobasso’s Contributions W to Music and Film For May, we are planning to have a two-part program called “At the Table with Tony.” Tony Scilla is a relatively new AMHS member who will offer one program on the cuisine of Abruzzo and another on 08 Siamo Una Famiglia the cuisine of Molise. The events, to be held on separate Sunday afternoons, are being organized by Program Committee member Chris Renneker. Stay tuned for further details. 09 AMHS Membership Then on Saturday, June 12, at 8 p.m., we are pleased to offer a program based on the documentary “Funke” which profiles professional chef and pasta expert Evan Funke. Special guests will be the 10 Campo di Giove producer/director Gab Taraboulsy, and the producer/editor Alex Emanuele. The event, which will be in an interview format, is being organized by Program Committee member Lourdes Tinajero. -

Archbishop Gaetano Bedini, Alessandro Gavazzi, and the Struggle to Define Republican Liberty in a Revolutionary Age, 1848-1854

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Transatlantic Tales and Democratic Dreams: Archbishop Gaetano Bedini, Alessandro Gavazzi, and the Struggle to Define Republican Liberty in a Revolutionary Age, 1848-1854 Andrew Mach West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Mach, Andrew, "Transatlantic Tales and Democratic Dreams: Archbishop Gaetano Bedini, Alessandro Gavazzi, and the Struggle to Define Republican Liberty in a Revolutionary Age, 1848-1854" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 107. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/107 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transatlantic Tales and Democratic Dreams: Archbishop Gaetano Bedini, Alessandro Gavazzi, and the Struggle to Define Republican Liberty in a Revolutionary Age, 1848-1854 Andrew Mach Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Brian Luskey, Ph.D., Chair Aaron Sheehan-Dean, Ph.D. -

The Catholic Church in the Czech Republic

The Catholic Church in the Czech Republic Dear Readers, The publication on the Ro- man Catholic Church which you are holding in your hands may strike you as history that belongs in a museum. How- ever, if you leaf through it and look around our beauti- ful country, you may discover that it belongs to the present as well. Many changes have taken place. The history of the Church in this country is also the history of this nation. And the history of the nation, of the country’s inhabitants, always has been and still is the history of the Church. The Church’s mission is to serve mankind, and we want to fulfil Jesus’s call: “I did not come to be served but to serve.” The beautiful and unique pastoral constitution of Vatican Coun- cil II, the document “Joy and Hope” begins with the words: “The joys and the hopes, the grief and the anxieties of the men of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted, these are the joys and hopes, the grief and anxieties of the followers of Christ.” This is the task that hundreds of thousands of men and women in this country strive to carry out. According to expert statistical estimates, approximately three million Roman Catholics live in our country along with almost twenty thousand of our Eastern broth- ers and sisters in the Greek Catholic Church, with whom we are in full communion. There are an additional million Christians who belong to a variety of other Churches. Ecumenical cooperation, which was strengthened by decades of persecution and bullying of the Church, is flourishing remarkably in this country. -

JOHN W. O Malley, S.J

JESUIT SCHOOLS AND THE HUMANITIES YESTERDAY AND TODAY ashington, D.C. 20036-5727 Jesuit Conference, Inc. 1016 16th St. NW Suite 400 W SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION, EFFECTIVE JANUARY 2015 The Seminar is composed of a number of Jesuits appointed from their prov- U.S. JESUITS inces in the United States. An annual subscription is provided by the Jesuit Conference for U.S. Jesuits living in the United The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice States and U.S. Jesuits who are still members of a U.S. Province but living outside the United of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and gathers current scholarly stud- States. ies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. ALL OTHER SUBSCRIBERS It then disseminates the results through this journal. All subscriptions will be handled by the Business Offce U.S.: One year, $22; two years, $40. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, other Canada and Mexico: One year, $30; two years, $52. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) priests, religious, and laity. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclusively for them. Others who may fnd them Other destinations: One year: $34; two years, $60. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) helpful are cordially welcome to read them at: [email protected]/jesuits . ORDERING AND PAYMENT Place orders at www.agrjesuits.com to receive Discount If paying by check - Make checks payable to: Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality Payment required at time of ordering and must be made in U.S. -

Manoscritti Tonini

Manoscritti Tonini strumento di corredo al fondo documentario a cura di Maria Cecilia Antoni Biblioteca Civica Gambalunga. Rimini. 2013 1 Il Fondo Tonini entrò in biblioteca nel 1924, in agosto una prima parte: più di 1500 fra volumi e opuscoli e dieci buste di manoscritti...e tutti i manoscritti, codici e pergamene appartenuti ai Tonini, custoditi dai fratelli Ricci,1 il resto in dicembre, in una stanza al piano terra di palazzo Gambalunga; il 26 aprile 1925 viene trasmessa al Sindaco di Rimini una Relazione degli esecutori testamentari: Alessandro Tosi e padre Gregorio Giovanardi2. La relazione, dattiloscritta, intitolata: Elenco manoscritti, opuscoli, libri di Luigi e Carlo Tonini, donati alla Biblioteca Gambalunga descrive nove nuclei contrassegnati da lettere alfabetiche (A-I) e da capoversi, interni ai nuclei, numerati progressivamente da 1 a 733; i nuclei A-F sono preceduti dal titolo: Luigi Tonini 4; il nucleo G è invece intitolato: Manoscritti di Carlo Tonini 5; seguono H: Pergamene (nn.47-53); I: Raccolta di documenti riguardanti la storia di Rimini ed altri luoghi, originali ed in copia. Questa descrizione tuttavia non permetteva più il rinvenimento dei documenti a causa di interventi, spostamenti e condizionamenti successivi6. 1 Articolo di G. GIOVANARDI, "La Riviera Romagnola", 11 settembre 1924, da cui è tratta la citazione sopra riportata. Nell'articolo Giovanardi individua dieci contenitori con lettere dell'alfabeto, da lui riordinati in questo modo: Busta A, Busta B, Busta C, contenenti le Vite d'insigni italiani di Carlo Tonini; Busta E con Epigrafi di Luigi e Carlo Tonini; Busta F Lavori di storia patri inediti di Luigi Tonini (tali Lavori sono numerati da I a XIV; i numeri XIII e XIV rimandano a volumi mss. -

Hidden Treasure

Longtime owner Anthony Antonelli. 56 RHODE ISLAND MONTHLY l FEBRUARY 2013 : TREASURE HIDDEN A holdout in the jewelry business that’s still going strong, Wolf E. Myrow’s beads and baubles have inspired generations of artists and jewelry designers. By Paul E. Kandarian I Photographs by Michael Cevoli RHODE ISLAND MONTHLY l FEBRUARY 2013 57 Anthony Antonelli doesn’t know how much inventory he has. But he knows exactly where all of it is. NeedA a little plastic Texas flag? He’ll find it. A tiny, pipe-smoking walrus? Not a problem. All manner of beads, baubles, buckles, bows and stones of every conceivable shape, color and size? Give him a minute, he’ll put his finger on whatever you need. Antonelli, his wife, Irene, and their two grown children, Tony and Robin, are the lifeblood of their company, Wolf E. Myrow, which for more than sixty years has been a huge presence in the jewelry-fitting industry, those little doodads that are the embryos of future bracelets, earrings, necklaces, artwork and everything in between. Ask what each does, they’ll smile and say, “whatever needs to be done.” Their business, known on the Internet as Closeout Jewelry Findings, is located in ancient buildings that once were Atlantic Mills on Providence’s Aleppo Street, a company that pro- cessed wool for Union soldier uniforms in the Civil War. All around are shelves crowded with well-worn boxes; attached to the outside of each is a sample of the contents within. In the massive warehouse just beyond are rooms of tall metal shelves heavy with boxes, manna from heaven for jewelry makers and artists who make their way here from around the world in search of goods and, more often than not, inspiration for what to create from them. -

Diocese of San Jose 2020 Directory

Diocese of San Jose 2020 Directory 1150 North First Street, Suite 100 San Jose, California 95112 Phone (408) 983-0100 www.dsj.org updated 10/8/2020 1 2 Table of Contents Diocese Page 5 Chancery Office Page 15 Deaneries Page 29 Churches Page 43 Schools Page 163 Clergy & Religious Page 169 Organizations Page 205 Appendix 1 Page A-1 Appendix 2 Page A-15 3 4 Pope Francis Bishop of Rome Jorge Mario Bergoglio was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina's capital city, on December 17, 1936. He studied and received a master's degree in chemistry at the University of Buenos Aires, but later decided to become a Jesuit priest and studied at the Jesuit seminary of Villa Devoto. He studied liberal arts in Santiago, Chile, and in 1960 earned a degree in philosophy from the Catholic University of Buenos Aires. Between 1964 and 1965 he was a teacher of literature and psychology at Inmaculada High School in the province of Santa Fe, and in 1966 he taught the same courses at the prestigious Colegio del Salvador in Buenos Aires. In 1967, he returned to his theological studies and was ordained a priest on December 13, 1969. After his perpetual profession as a Jesuit in 1973, he became master of novices at the Seminary of Villa Barilari in San Miguel. Later that same year, he was elected superior of the Jesuit province of Argentina and Uruguay. In 1980, he returned to San Miguel as a teacher at the Jesuit school, a job rarely taken by a former provincial superior. -

Pilgrimage to Our Past

PILGRIMAGE TO UR AST O P Celebrating 200/225 Years of Students & Parishioners for Others October 2018 The Founding of Trinity Church A Milestone in American Catholic History Holy Trinity, founded in 1787, is the oldest Roman Catholic Going forward, and parish in the District of Columbia. Its longevity is a point of with the first Mass held pride for parishioners today. Of further interest is that the in the Chapel in 1784, establishment of Holy Trinity and the construction of its Catholics would ex- church represented a major change in the way Catholics of press their faith public- the region had worshipped for the better part of a century. ly and free of persecu- tion. The colony of Mary- land, including the ar- ea that is now the Dis- trict of Columbia, was settled in 1634. It is widely known as the Catholic colony be- cause its Catholic founders sought free- dom of worship at a time when such free- Photo border from past dom was unavailable to Catholics in other colonies. Its lead- and current students ers and landowners were prominent English Catholic noble- men, but Catholics represented only a sixth of Maryland’s early population, the remainder of the settlers being Protestants. Jesuit priests, among the first arrivals in the colony, served the religious needs of the Catholic colonists. When the Protestant majority eventually gained political control, the Maryland Assembly in 1704 prohibited Catholic priests from saying Mass or performing other priestly func- tions. Maryland Catholics adopted a course of private worship by attending Mass at Jesuit manor houses or performing devo- tions at home. -

Resignations and Appointments

N. 200708b Wednesday 08.07.2020 Resignations and Appointments Resignation of auxiliary of Włocławek, Poland Appointment of bishop of Savannah, U.S.A. Appointment of vicar apostolic of Yurimaguas, Peru Appointment of auxiliary of the metropolitan archdiocese of São Paulo, Brazil Appointment of members of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue Resignation of auxiliary of Włocławek, Poland The Holy Father has accepted the resignation from the office of auxiliary of the diocese of Włocławek, Poland, presented by Bishop Stanisław Gębicki. Appointment of bishop of Savannah, U.S.A. The Holy Father has appointed as bishop of Savannah, United States of America, the Reverend Stephen D. Parkes, of the clergy of the diocese of Orlando, Florida, currently vicar forane of the deanery of the Central Deanery North and parish priest of the Annunciation parish in Altamonte Springs. Reverend Stephen D. Parkes 2 The Reverend Stephen D. Parkes was born on 2 June 1965 in Mineola, New York, in the diocese of Rockville Centre. He attended Massapequa High School in New York (1979-1983) and was awarded a bachelor’s degree in business administration and marketing from the University of South Florida in Tampa (1983-1987). He worked in business and banking. He entered the Seminary and completed his ecclesiastical studies at Saint Vincent de Paul Regional Seminary in Boyton Beach, Florida (1992-1998). He was ordained priest for the diocese of Orlando, Florida on 23 May 1998. Since priestly ordination he held the following positions: parish vicar of the Annunciation parish in Altamonte Springs (1998-2005); administrator and founding pastor of the Most Precious Blood parish in Oviedo (2005- 2011); spiritual director of university pastoral care at the University of Central Florida in Orlando (2004-2011); vicar forane of Central Deanery North (2010-2020); pastor of the Annunciation parish at Altamonte Springs (2011-2020); spiritual director of the Board of the Catholic Foundation of Central Florida (2009-2020) and secretary of the presbyteral council. -

Glossary, Bibliography, Index of Printed Edition

GLOSSARY Bishop A member of the hierarchy of the Church, given jurisdiction over a diocese; or an archbishop over an archdiocese Bull (From bulla, a seal) A solemn pronouncement by the Pope, such as the 1537 Bull of Pope Paul III, Sublimis Deus,proclaiming the human rights of the Indians (See Ch. 1, n. 16) Chapter An assembly of members, or delegates of a community, province, congregation, or the entire Order of Preachers. A chapter is called for decision-making or election, at intervals determined by the Constitutions. Coadjutor One appointed to assist a bishop in his diocese, with the right to succeed him as its head. Bishop Congregation A title given by the Church to an approved body of religious women or men. Convent The local house of a community of Dominican friars or sisters. Council The central governing unit of a Dominican priory, province, congregation, monastery, laity and the entire Order. Diocese A division of the Church embracing the members entrusted to a bishop; in the case of an archdiocese, an archbishop. Divine Office The Liturgy of the Hours. The official prayer of the Church composed of psalms, hymns and readings from Scripture or related sources. Episcopal Related to a bishop and his jurisdiction in the Church; as in "Episcopal See." Exeat Authorization given to a priest by his bishop to serve in another diocese. Faculties Authorization given a priest by the bishop for priestly ministry in his diocese. Friar A priest or cooperator brother of the Order of Preachers. Lay Brother A term used in the past for "cooperator brother." Lay Dominican A professed member of the Dominican Laity, once called "Third Order." Mandamus The official assignment of a friar or a sister to a Communit and ministry related to the mission of the Order.