Stjohn's Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Composer Vladimir Jovanović and His Role in the Renewal of Church Byzantine Music in Serbia from the 1990S Until Today

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 19, 2019 @PTPN Poznań 2019, DOI 10.14746/ism.2019.19.1 GORDANA BLAGOJEVIĆ https://orcid.org/0000–0001–7883–8071 Institute of Ethnography SASA, Belgrade Contemporary composer Vladimir Jovanović and his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today ABSTRACT: This work focuses on the role of the composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović in the rene- wal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today. This multi-talented artist wor- ked and created art in his native Belgrade, with creativity that exceeded local frames. This research emphasizes Jovanović’s pedagogical and compositional work in the field of Byzantine music, which mostly took place through his activity in the St. John of Damascus choir in Belgrade. The author analyzes the problems in implementation of modal church Byzantine music, since the first students did not hear it in their surroundings, as well as the responses of the listeners. Special attention is paid to students’ narratives, which help us perceive the broad cultural and social impact of Jovanović’s creative work. KEYWORDS: composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović, church Byzantine music, modal music, St. John of Damascus choir. Introduction This work was written in commemoration of a contemporary Serbian composer1 Vladimir Jovanović (1956–2016) with special reference to his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the beginning of the 1990s until today.2 In the text we refer to Vladimir Jovanović as Vlada – a shortened form of his name, which relatives, friends, colleagues and students used most of- ten in communication with the composer, as an expression of sincere closeness. -

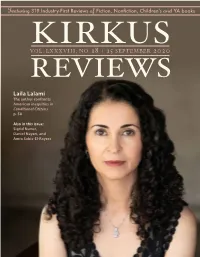

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

The Bear in Eurasian Plant Names

Kolosova et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2017) 13:14 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0132-9 REVIEW Open Access The bear in Eurasian plant names: motivations and models Valeria Kolosova1*, Ingvar Svanberg2, Raivo Kalle3, Lisa Strecker4,Ayşe Mine Gençler Özkan5, Andrea Pieroni6, Kevin Cianfaglione7, Zsolt Molnár8, Nora Papp9, Łukasz Łuczaj10, Dessislava Dimitrova11, Daiva Šeškauskaitė12, Jonathan Roper13, Avni Hajdari14 and Renata Sõukand3 Abstract Ethnolinguistic studies are important for understanding an ethnic group’s ideas on the world, expressed in its language. Comparing corresponding aspects of such knowledge might help clarify problems of origin for certain concepts and words, e.g. whether they form common heritage, have an independent origin, are borrowings, or calques. The current study was conducted on the material in Slavonic, Baltic, Germanic, Romance, Finno-Ugrian, Turkic and Albanian languages. The bear was chosen as being a large, dangerous animal, important in traditional culture, whose name is widely reflected in folk plant names. The phytonyms for comparison were mostly obtained from dictionaries and other publications, and supplemented with data from databases, the co-authors’ field data, and archival sources (dialect and folklore materials). More than 1200 phytonym use records (combinations of a local name and a meaning) for 364 plant and fungal taxa were recorded to help find out the reasoning behind bear-nomination in various languages, as well as differences and similarities between the patterns among them. Among the most common taxa with bear-related phytonyms were Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng., Heracleum sphondylium L., Acanthus mollis L., and Allium ursinum L., with Latin loan translation contributing a high proportion of the phytonyms. -

Recent Publications in Music 2009

Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol. 56/4 (2009) RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC R1 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2009 On behalf of the International Association of Music Libraries Archives and Documentation Centres / Pour le compte l'Association Internationale des Bibliothèques, Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux / Im Auftrag der Die Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2008. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in the IAML journal Fontes Artis Musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compiler welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove Reporters: Austria: Thomas Leibnitz Canada: Marlene Wehrle China, Hong Kong, Taiwan: Katie Lai Croatia: Zdravko Blaţeković Czech Republic: Pavel Kordík Estonia: Katre Rissalu Finland: Ulla Ikaheimo, Tuomas Tyyri France: Cécile Reynaud Germany: Wolfgang Ritschel Ghana: Santie De Jongh Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis Hungary: Szepesi Zsuzsanna Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir Ireland: Roy Stanley Italy: Federica Biancheri Japan: Sekine Toshiko Namibia: Santie De Jongh The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina South Africa: Santie De Jongh Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José González Ribot Sweden Turkey: Paul Alister Whitehead, Senem Acar United States: Karen Little, Liza Vick. With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, D. -

LBW: Public-2

Chav compositor composicao Ano Detalhes duração Intérpretes ? Cembalo nach A. Vivaldi * Abel, Carl Fried Sonate für Viola da Gamb 1723-1 5'10 Veronika Hampe - Gambe Abel, K.F. Sonate für Viola da Gamb 1723-1 Abel, K.F. Sonate K 176 für Gitarren 1723-1 Moderato; 6'50 D.E. Lovell - Synth. Cantabile; Vivace Abel, K.F. Sonate K 176 für Gitarren 1723-1 Moderato; 6'50 D.E. Lovell - Synth. Cantabile; Vivace Adson, J. Aria für Flöte und BC 2'00 (P) 1969 Discos beverly LTDA conjunto musikantiga de são paulo Adson, J. Courtly masquino ayres 3 1590-1 5'06 (P) 1968 rozenblit conjunto musikantiga de são paulo Alain, Jehan 2 Stücke für Orgel 1911-1 Marie-Claire Alain Albéniz, I. Danzas españolas Op.37 1860-1 2-Tango; 2' Nr. ?? Tango 3-Malagueña Nr. 2: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Nr. 3: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Albéniz, I. Estudio sem luz 1860-1 3' Albéniz, I. Suite Española Op. 47 1860-1 Für Orchester 37'16 5. Asturias gesetzt von Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos 1. Granada (Serenata); 2. Cataluna (Curranda); 3. Sevilla; 4. Cádiz (Saeta); 5. Astúrias (arr. A. Segovia) (Leyenda); 6.Aragon (Fantasia); 7.Castilla (Sequidillas); 8. Cuba (Nocturno) Chav compositor composicao Ano Detalhes duração Intérpretes Orchesterzusatz: 8. Cordoba Nr. 1 Granada: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Nr. 1 Granada (5'20) : Julien Bream - Gitarre (P) 1968 DECCA Reihenfolge: 7, 5, 6, 4, 3, 1, 2, 8 New Philharmonia Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos Albicastro, H. Concerto Op. 7 Nr. 6 F-Du 1659-1 9'20 Süsdwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzheim Leitung: Paul Angerer Albinoni, T. -

![Werner-B02c[Erato-10CD].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2163/werner-b02c-erato-10cd-pdf-1912163.webp)

Werner-B02c[Erato-10CD].Pdf

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) The Cantatas, Volume 2 Heinrich Schütz Choir, Heilbronn Pforzheim Chamber Orchestra Württemberg Chamber Orchestra (B\,\1/ 102, 137, 150) Südwestfunk Orchestra, Baden-Baden (B\,\ry 51, 104) Fritz Werner L'Acad6mie Charles Cros, Grand Prix du disque (BWV 21, 26,130) For complete cantata texts please see www.bach-cantatas.com/IndexTexts.htm cD t 75.22 Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, BWV 2l My heart and soul were sore distrest . Mon cceur ötait plein d'ffiiction Domenica 3 post Trinitatis/Per ogni tempo Cantata for the Third Sunday after Trinity/For any time Pour le 3n"" Dimanche aprös la Trinitö/Pour tous les temps Am 3. Sonntag nachTrinitatis/Für jede Zeit Prima Parte 0l 1. Sinfonia 3.42 Oboe, violini, viola, basso continuo 02 2. Coro; Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis 4.06 Oboe, violini, viola, fagotto, basso continuo 03 3. Aria (Soprano): Seufzer, Tränen, Kummer, Not 4.50 Oboe, basso continuo ) 04 4. Recitativo (Tenore): Wie hast du dich, mein Gott 1.50 Violini, viola, basso continuo 05 5. Aria (Tenore): Bäche von gesalznen Zähren 5.58 Violini, viola, basso conlinuo 06 6. Coro: Was betrübst du dich, meine Seele 4.35 Oboe, violini, viola, fagotto, basso continuo Seconda Parte 07 7. Recitativo (Soprano, Basso): Ach Iesu, meine Ruh 1.38 Violini, viola, basso continuo 08 8. Duetto (Soprano, Basso): Komm, mein Jesu 4.34 Basso continuo 09 9. Coro: Sei nun wieder zufrieden 6.09 Oboe, tromboni, violini, viola, fagotto, basso continuo l0 10. Aria (Tenore): Erfreue dich, Seele 2.52 Basso continuo 11 11. -

Matica Srpska Department of Social Sciences Synaxa Matica Srpska International Journal for Social Sciences, Arts and Culture

MATICA SRPSKA DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCES SYNAXA MATICA SRPSKA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR SOCIAL SCIENCES, ARTS AND CULTURE Established in 2017 2–3 (1–2/2018) Editor-in-Chief Časlav Ocić (2017‒ ) Editorial Board Dušan Rnjak Katarina Tomašević Editorial Secretary Jovana Trbojević Language Editor and Proof Reader Aleksandar Pavić Articles are available in full-text at the web site of Matica Srpska http://www.maticasrpska.org.rs/ Copyright © Matica Srpska, Novi Sad, 2018 SYNAXA СИН@КСА♦ΣΎΝΑΞΙΣ♦SYN@XIS Matica Srpska International Journal for Social Sciences, Arts and Culture 2–3 (1–2/2018) NOVI SAD 2018 Publication of this issue was supported by City Department for Culture of Novi Sad and Foundation “Novi Sad 2021” CONTENTS ARTICLES AND TREATISES Srđa Trifković FROM UTOPIA TO DYSTOPIA: THE CREATION OF YUGOSLAVIA IN 1918 1–18 Smiljana Đurović THE GREAT ECONOMIC CRISIS IN INTERWAR YUGOSLAVIA: STATE INTERVENTION 19–35 Svetlana V. Mirčov SERBIAN WRITTEN WORD IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR: STRUGGLING FOR NATIONAL AND STATEHOOD SURVIVAL 37–59 Slavenko Terzić COUNT SAVA VLADISLAVIĆ’S EURO-ASIAN HORIZONS 61–74 Bogoljub Šijaković WISDOM IN CONTEXT: PROVERBS AND PHILOSOPHY 75–85 Milomir Stepić FROM (NEO)CLASSICAL TO POSTMODERN GEOPOLITICAL POSTULATES 87–103 Nino Delić DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS IN THE DISTRICT OF SMEDEREVO: 1846–1866 105–113 Miša Đurković IDEOLOGICAL AND POLITICAL CONFLICTS ABOUT POPULAR MUSIC IN SERBIA 115–124 Mirjana Veselinović-Hofman TOWARDS A BOTTOMLESS PIT: THE DRAMATURGY OF SILENCE IN THE STRING QUARTET PLAY STRINDBERG BY IVANA STEFANOVIĆ 125–134 Marija Maglov TIME TIIIME TIIIIIIME: CONSIDERING THE PROBLEM OF MUSICAL TIME ON THE EXAMPLE OF VLASTIMIR TRAJKOVIĆ’S POETICS AND THOMAS CLIFTON’S AESTHETICS 135–142 Milan R. -

Sacred & Secular Vocal

SACRED & SECULAR VOCAL SACRED WORKS BACH 333 BACH 1 2 BACH 333 SACRED WORKS SACRED AND SECULAR VOCAL Tracklists Chorales 2 Magnificat, Motets, Masses, Passions, Oratorios 16 Secular Cantatas 68 Vocal Traditions 92 Sung texts Chorales 160 Magnificat, Motets, Masses 205 St John Passion 214 St Matthew Passion 234 Easter Oratorio 263 Ascension Oratorio 265 Christmas Oratorio 268 Secular Cantatas 283 CD 49 68:51 4-Part Chorales Sung texts pp. 160–174 1 Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan BWV 250 0:53 2 Sei Lob und Ehr dem höchsten Gut BWV 251 0:53 3 Nun danket alle Gott BWV 252 0:52 Kölner Akademie | Michael Alexander Willens conductor 4 Ach bleib bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 253 0:38 5 Ach Gott, erhör mein Seufzen und Wehklagen BWV 254 0:48 6 Ach Gott und Herr BWV 255 0:36 7 Ach lieben Christen, seid getrost BWV 256 0:57 Augsburger Domsingknaben | Reinhard Kammler conductor CHORALES Claudia Waßner organ 8 Wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit BWV 257 0:55 9 Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns hält BWV 258 0:56 Vocalconsort Berlin | Daniel Reuss conductor Ophira Zakai lute | Elina Albach organ BACH 333 BACH 4 10 Ach, was soll ich Sünder machen BWV 259 0:55 11 Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr BWV 260 0:56 12 Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 261 1:13 13 Alle Menschen müssen sterben BWV 262 0:57 14 Alles ist an Gottes Segen BWV 263 0:42 15 Als der gütige Gott BWV 264 1:22 16 Als Jesus Christus in der Nacht BWV 265 1:42 17 Als vierzig Tag nach Ostern warn BWV 266 0:48 18 An Wasserflüssen Babylon BWV 267 1:23 19 Auf, auf, mein Herz, und du mein ganzer Sinn -

Titel Kino 4/2000 Nr. 1U.2

EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 4/2000 Special Report: TRAINING THE NEXT GENERATION – Film Schools In Germany ”THE TANGO DANCER“: Portrait of Jeanine Meerapfel Selling German Films: CINE INTERNATIONAL & KINOWELT INTERNATIONAL Kino Scene from:“A BUNDLE OF JOY” GERMAN CINEMA Launched at MIFED 2000 a new label of Bavaria Film International Further info at www.bavaria-film-international.de www. german- cinema. de/ FILMS.INFORMATION ON GERMAN now with links to international festivals! GERMAN CINEMA Export-Union des Deutschen Films GmbH · Tuerkenstrasse 93 · D-80799 München phone +49-89-3900 9 5 · fax +49-89-3952 2 3 · email: [email protected] KINO 4/2000 6 Training The Next Generation 33 Soweit die Füße tragen Film Schools in Germany Hardy Martins 34 Vaya Con Dios 15 The Tango Dancer Zoltan Spirandelli Portrait of Jeanine Meerapfel 34 Vera Brühne Hark Bohm 16 Pursuing The Exceptional 35 Vill Passiert In The Everyday Wim Wenders Portrait of Hans-Christian Schmid 18 Then She Makes Her Pitch Cine International 36 German Classics 20 On Top Of The Kinowelt 36 Abwärts Kinowelt International OUT OF ORDER Carl Schenkel 21 The Teamworx Player 37 Die Artisten in der Zirkuskuppel: teamWorx Production Company ratlos THE ARTISTS UNDER THE BIG TOP: 24 KINO news PERPLEXED Alexander Kluge 38 Ehe im Schatten MARRIAGE IN THE SHADOW 28 In Production Kurt Maetzig 39 Harlis 28 B-52 Robert van Ackeren Hartmut Bitomsky 40 Karbid und Sauerampfer 28 Die Champions CARBIDE AND SORREL Christoph Hübner Frank Beyer 29 Julietta 41 Martha Christoph Stark Rainer Werner Fassbinder 30 Königskinder Anne Wild 30 Mein langsames Leben Angela Schanelec 31 Nancy und Frank Wolf Gremm 32 Null Uhr Zwölf Bernd-Michael Lade 32 Das Sams Ben Verbong CONTENTS 50 Kleine Kreise 42 New German Films CIRCLING Jakob Hilpert 42 Das Bankett 51 Liebe nach Mitternacht THE BANQUET MIDNIGHT LOVE Holger Jancke, Olaf Jacobs Harald Leipnitz 43 Doppelpack 52 Liebesluder DOUBLE PACK A BUNDLE OF JOY Matthias Lehmann Detlev W. -

RECENT PUBLICATIONS in MUSIC 2013 Page 1 of 154

RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2013 Page 1 of 154 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2013 Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove and David Sommerfield This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared primarily in 2012. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in conjuction with Fontes artis musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the editor of Fontes welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. CONTRIBUTORS. Argentina: Estela Escalada Kenya: Santie De Jongh Austria: Thomas Leibnitz Macau SAR: Katie Lai Belgium: Johan Eeckeloo Malawi: Santie De Jongh Canada: Sean Luyk The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert China: Katie Lai New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Czech Republic: Pavel Kordik Nigeria: Santie De Jongh Denmark: Anne Ørbæk Jensen Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina Estonia: Katre Rissalu Serbia: Radmila Milinković Finland: Tuomas Tyyri South Africa: Santie De Jongh France: Élisabeth Missaoui Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José Germany: Susanne Heim González Ribot Greece: George Boumpous, Stephanie Sweden: Kerstin Carpvik, Lena Nettelbladt Merakos Taiwan: Katie Lai Hong Kong SAR: Katie Lai Turkey: Senem Acar, Paul Alister Whitehead Hungary: SZEPESI Zsuzsanna Uganda: Santie De Jongh Ireland: Roy Stanley United Kingdom: Rupert Ridgewell Italy: Federica Biancheri United States: Matt Ertz, Lindsay Hansen. Japan: SEKINE Toshiko With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, Maureen Buja, Ana Cristán, Paul Frank, Dr. -

Transpositions-Abstracts

XIII. International Conference of the Department of Musicology 23 TRANSPOSITIONS: MUSIC/IMAGE XIII. International Conference of the Department of Musicology Faculty of Music University of Arts in Belgrade Belgrade, 12–15 October 2016 ABSTRACTS & BIOGRAPHIES 24 TRANSPOSITIONS: MUSIC/IMAGE KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Albrecht Riethmüller, PhD Institut für Theaterwissenschaft, Seminar für Musikwissenschaft, Freie Universität, Berlin From Dragonfly to Space Flight. On Kinetic Concepts between Music and Motion Picture Transposition, alteration, variation, modulation, and locomotion belong to the circle of kinetic concepts, which, since ancient Greek philosophy and music theory, have designated various kinds of motion. Most of them have achieved prominence throughout the history of musical terminology in many languages. The lecture’s principle subject is the transfer of the kinetic mode of flying, and/ or flight, to music and film. Traditionally, musicians and music theorists have dealt with birdsong, not a bird’s flying capabilities, when dealing with the imita- tion of nature. In the age of realism in art and literature, however, close observa- tion of natural processes has also brought composers to attend to flying objects such as the dragonfly (Josef Strauss) or bumblebee (Rimsky-Korsakov). But it was not until after the invention of human aviation’s artificial imitation of flight that composers began to turn to the sphere of flying as an inspiration (think of Weill’s and Brecht’s Lindberghflug or Dallapiccola’s Volo di note), which was also simultaneous with the development of moving images in film. The summit of the interaction of motion, speed, and standstill with respect to music and film seems to be flights in space; examples of this will be drawn from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 – A Space Odyssey (1968), and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s operatic cycle Licht (since 1981). -

Recent Publications in Music 2012

1 of 149 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2012 Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove and David Sommerfield This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2011. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in conjuction with Fontes artis musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compilers welcome inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. CONTRIBUTORS. Argentina: Estela Escalada Japan: SEKINE Toshiko Australia: Julia Mitford Kenya: Santie De Jongh Austria: Thomas Leibnitz Malawi: Santie De Jongh Belgium: Johan Eeckeloo Mexico: Daniel Villanueva Rivas, María Del China: Katie Lai Consuelo García Martínez Croatia: Žeiljka Radovinović The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert Denmark: Anne Ørbæk Jensen New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Estonia: Katre Rissalu Nigeria: Santie De Jongh Finland: Tuomas Tyyri Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina France: Élisabeth Missaoui Serbia: Radmila Milinković Germany: Susanne Hein South Africa: Santie De Jongh Ghana: Santie De Jongh Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis González Ribot Greenland: Anne Ørbæk Jensen Taiwan: Katie Lai Hong Kong: Katie Lai Turkey: Senem Acar, Paul Alister Whitehead Hungary: SZEPESI Zsuzsanna Uganda: Santie De Jongh Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir United Kingdom: Rupert Ridgewell Ireland: Roy Stanley United States: Karen Little, Lindsay Hansen Italy: Federica Biancheri Uruguay: Estela Escalada With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, Ana Cristán, Paul Frank, Irina Kirchik, Everette Larson, Miroslava Nezar, Joan Weeks, and Thompson A.