The Mining Industries, 1899-1939: a Study of Output, Employment, and Productivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alabama Mine Map Repository

ALABAMA MINE MAP REPOSITORY DIRECTORY OF UNDERGROUND MINE MAPS STATE OF ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF LABOR Fitzgerald Washington Commissioner INSPECTIONS DIVISION Brian J. Wittwer Acting Director ABANDONED MINE LAND PROGRAM Chuck Williams State Mine Land Reclamation Supervisor ALABAMA MINE MAP REPOSITORY DIRECTORY OF UNDERGROUND MINE MAPS By, Charles M. Whitson, PE Mining Engineer Birmingham, Alabama 2013 CONTENTS Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Users of the Repository ………………………………………………………………. 1 Source of the Maps ……………………………………………………………………… 1 Repository Location ……………………………………………………………………… 1 Request to Readers ……………………………………………………………………… 2 Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………… 2 History …………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 The United States Public Land Survey System (PLSS) ……………… 4 Explanation of the Files in the Repository …………………………………. 8 Active Mines ……………………………………………………………………… 8 Abandoned Mines ……………………………………………………………… 8 Disclaimer ……………………………………………………………………………………. 10 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………………………. 11 Directory ………………………………………………………………………………………. 13 Active Underground Mines ………………………………………………… 14 Abandoned Underground Coal Mines Bibb County ……………………………………………………………. 18 Blount County …………………………………………………………. 24 Cherokee County ……………………………………………………. 27 Cullman County ………………………………………………………. 28 DeKalb County ………………………………………………………… 30 Etowah County ……………………………………………………….. 31 Fayette County ………………………………………………………. 33 Jackson County ……………………………………………………… 34 Jefferson County ……………………………………………………. 36 Lawrence -

Canadian Rail No158 1964

C;a:n..a )~~iin Number 158 / September 1964 GOVERNMENT OWNERSHIP of railways in Canada occurs at all levels, and not the least interesting is the Pacific Great East ern, which is owned by the Province of British Columbi'l.. For many years, the PGE began and ended nowhere, but in 1952 and 1956, the completion of extensions linked the "nowhere" carrier with the rest of the Canadian rail network. Here, in the latter year, the inaugural train is shown arriving from North Vancouver at Squamish, the erstwhile southern terminus of the line. (See "The PGE Is A rDiffe~entr Railway" in this issue). Photograph by PETER COX. Canadian Rail Page 179 ~ontreal Streetcars 900 by R. M. Binns Class (M.S.R. Photos) By mid-December 1904 about class),- and probably on the new half of the fifty 790 class semi 790 class, had fo~ned the habit convertible cars were in service. of collecting fares on the plat Well satisfied with these cars, form at stops where only one or the first to have transverse two passeng ers got on. seats, - Montre al ~tre d t Hailway Co. was authorized by its 80ard The "Pay-as-You-~nter" me of Directors to build twenty-five thod had been tried on one or two more, at a cost of $6000 each - roads in the United States, but all to be built in the Company's without success. It was clear shops. Ten cars were to be equip that the conventiona l car was not ped with General ~lectric Co.'s adapted to that system. -

Rail Heritage Managed by the Department of Conservation West Coast Charming Creek Walkway, 1910-1958, Near Westport

Prepared by Paul Mahoney, National Coordinator Rail Heritage managed by the Historic Heritage, Department of Conservation. Department of Conservation June 2007 The Department manages a diverse range of rail heritage sites that are becoming increasingly popular. In 2007 the Automobile Association asked over 20,000 New Zealanders to identify the '101 Must-Do’s for Kiwis' — places they most wanted to visit. Of all DOC's historic sites two rail heritage sites were the most popular; the Central Otago Rail Trail (14th) and the Karangahake Mines (42nd). Rail heritage sites are different from static museums and operating lines. They offer an adventure experience exploring remote and scenic trails, adding diversity to the overall rail heritage scene and providing further entry points to trigger peoples potential interest. DOC’s sites include an industrial railway focus; timber, gold, coal, and even lighthouses, and so preserve another category of rail heritage. The Department shares the expertise of its heritage program, such as the results of scientific research into materials conservation; stone, wood and metal. These 31 DOC sites are open to visitors: AucklandAuckland Kauri Timber Co tramline, 1925-40, Whangaparapara, Great Barrier Island. Route of bush tram 14km long. One of the most fantastic bush trams ever. Includes 11 sections of incline worked by winch and cable. Tramping skills required. WaikatoWaikato Billy Goat incline, 1922-25, Kauaeranga Valley, Coromandel Forest Park. Route of bush tram 5 km long. A section of track is re-laid. A Price rail tractor will be restored and displayed. Karangahake Rail Trail, 1905-1978, Karangahake, near Paeroa. Route of the former East Coast Main Trunk railway from Karangahake to Waikino, 7 km long. -

~ Coal Mining in Canada: a Historical and Comparative Overview

~ Coal Mining in Canada: A Historical and Comparative Overview Delphin A. Muise Robert G. McIntosh Transformation Series Collection Transformation "Transformation," an occasional paper series pub- La collection Transformation, publication en st~~rie du lished by the Collection and Research Branch of the Musee national des sciences et de la technologic parais- National Museum of Science and Technology, is intended sant irregulierement, a pour but de faire connaitre, le to make current research available as quickly and inex- plus vite possible et au moindre cout, les recherches en pensively as possible. The series presents original cours dans certains secteurs. Elle prend la forme de research on science and technology history and issues monographies ou de recueils de courtes etudes accep- in Canada through refereed monographs or collections tes par un comite d'experts et s'alignant sur le thenne cen- of shorter studies, consistent with the Corporate frame- tral de la Societe, v La transformation du CanadaLo . Elle work, "The Transformation of Canada," and curatorial presente les travaux de recherche originaux en histoire subject priorities in agricultural and forestry, communi- des sciences et de la technologic au Canada et, ques- cations and space, transportation, industry, physical tions connexes realises en fonction des priorites de la sciences and energy. Division de la conservation, dans les secteurs de: l'agri- The Transformation series provides access to research culture et des forets, des communications et de 1'cspace, undertaken by staff curators and researchers for develop- des transports, de 1'industrie, des sciences physiques ment of collections, exhibits and programs. Submissions et de 1'energie . -

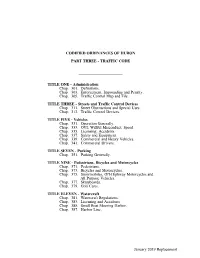

I:\My Files\Huron\D-TRAFFIC.Wpd

CODIFIED ORDINANCES OF HURON PART THREE - TRAFFIC CODE TITLE ONE - Administration Chap. 301. Definitions. Chap. 303. Enforcement, Impounding and Penalty. Chap. 305. Traffic Control Map and File. TITLE THREE - Streets and Traffic Control Devices Chap. 311. Street Obstructions and Special Uses. Chap. 313. Traffic Control Devices. TITLE FIVE - Vehicles Chap. 331. Operation Generally. Chap. 333. OVI; Willful Misconduct; Speed. Chap. 335. Licensing; Accidents. Chap. 337. Safety and Equipment. Chap. 339. Commercial and Heavy Vehicles. Chap. 341. Commercial Drivers. TITLE SEVEN - Parking Chap. 351. Parking Generally. TITLE NINE - Pedestrians, Bicycles and Motorcycles Chap. 371. Pedestrians. Chap. 373. Bicycles and Motorcycles. Chap. 375. Snowmobiles, Off-Highway Motorcycles and All Purpose Vehicles. Chap. 377. Skateboards. Chap. 379. Golf Carts. TITLE ELEVEN - Watercraft Chap. 381. Watercraft Regulations. Chap. 383. Licensing and Accidents. Chap. 385. Small Boat Mooring Harbor. Chap. 387. Harbor Line. January 2019 Replacement 3 CODIFIED ORDINANCES OF HURON PART THREE - TRAFFIC CODE TITLE ONE - Administration Chap. 301. Definitions. Chap. 303. Enforcement, Impounding and Penalty. Chap. 305. Traffic Control Map and File. CHAPTER 301 Definitions 301.01 Meaning of words and phrases. 301.26 Private road or driveway. 301.02 Agricultural tractor. 301.27 Public safety vehicle. 301.03 Alley. 301.28 Railroad. 301.031 Beacon; hybrid beacon. 301.29 Railroad sign or signal. 301.04 Bicycle; motorized bicycle; 301.30 Railroad train. moped. 301.31 Residence district. 301.05 Bus. 301.32 Right of way. 301.06 Business district. 301.321 Road service vehicle. 301.07 Commercial tractor. 301.33 Roadway. 301.08 Controlled-access highway. 301.34 Safety zone. 301.09 Crosswalk. -

Tools and Machinery of the Granite Industry Donald D

©2013 The Early American Industries Association. May not be reprinted without permission. www.earlyamericanindustries.org The Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association, Inc. Vol. 59, No. 2 June 2006 The Early American Industries Contents Association President: Tools and Machinery of the Granite Industry Donald D. Rosebrook Executive Director: by Paul Wood -------------------------------------------------------------- 37 Elton W. Hall THE PURPOSE of the Associa- Machines for Making Bricks in America, 1800-1850 tion is to encourage the study by Michael Pulice ----------------------------------------------------------- 53 of and better understanding of early American industries in the home, in the shop, on American Bucksaws the farm, and on the sea; also by Graham Stubbs ---------------------------------------------------------- 59 to discover, identify, classify, preserve and exhibit obsolete tools, implements and mechani- Departments cal devices which were used in early America. Stanley Tools by Walter W. Jacob MEMBERSHIP in the EAIA The Advertising Signs of the Stanley Rule & Level Co.— is open to any person or orga- Script Logo Period (1910-1920) ------------------------------------------- 70 nization sharing its interests and purposes. For membership Book Review: Windsor-Chair Making in America, From Craft Shop to Consumer by information, write to Elton W. Hall, Executive Nancy Goyne Evans Director, 167 Bakerville Road, Reviewed by Elton W. Hall ------------------------------------------------- 75 South Dartmouth, MA 02748 or e-mail: [email protected]. Plane Chatter by J. M. Whelan An Unusual Iron Mounting ------------------------------------------------- 76 The Chronicle Editor: Patty MacLeish Editorial Board Katherine Boardman Covers John Carter Front: A bucksaw, patented in 1859 by James Haynes, and a nineteenth century Jay Gaynor Raymond V. Giordano saw-buck. Photograph by Graham Stubbs, who discusses American bucksaws Rabbit Goody in this issue beginning on page 59. -

Power from Coal.Pdf

PHOTOS PROVIDED BY: AMAX Coal Industries, Inc. American Electric Power Service Corp. CONSOL, Inc. Peabody Holding Company, Inc. National Mining Association American Coal Foundation 101 Constitution Avenue NW, Suite 525 East Washington, DC 20001 202-463-9785 [email protected] www.teachcoal.org WHERE'S ALL THIS COAL COMING FROM? Take a minute to think about what you did this morning. You woke up, perhaps switched off the clock radio reached for the light switch, and went into the bathroom to wash your face, brush your teeth or take a hot shower. Did you use a hair dryer? Did you scramble an egg or toast a piece of bread for breakfast this morning? Did you play a video game or VCR? If you did any of these things, you were using electricity - a full- time energy servant that most Americans take for granted. There is something else you probably never think much about - coal. It's very likely you've never seen a piece of coal, although you may remember your grandparents talking about the coal they used to shovel into the furnace to heat their home. What's the connection? What does coal have to do with electricity? Isn't coal part of the past? Isn't electricity about as up-to-date as you can get? After all, it's electricity that allows us to watch television, use a computer, cook on the stove or in the microwave, enjoy stereo music, heat and cool our homes, read at night - all these things and dozens more that take place daily. -

Department of the Interior

DEPARTMENTOF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES BUREAU OF MINES JOHNW. FINCH*DIRCC~OFI INFORMATION CIRCULAR - PLACER MINING IN THE WESTERN UNlTED STATES - - PART Ill. DREDGING AND OTHER FORMS OF MECHANICAL. HANDLING OF GRAVEL, AND DRIFT MINING 1 I . .C. 6788. February 1935 Part I11 . .Dredeing and Other Forms of Mechanical Handling of Eravel . and Drift Miniqg CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................................................:..................... Acknowledgments ..................................................................:................................. Excavating by teams or power equipment ...................................................... General statement...................................................................................... Team or traotors...................................................................................... Teams .................................................................................................... Tractors.............................................................................................. Scrapers and hoists.................................................................................. Drag scrapers...... : ............................................................................. Slaokline on oablewags .................................................................. Power shovels and draglines.................................................................. Stationary washing plants........................................................... -

Dragline Maintenance Engineering

University of Southern Queensland Faculty of Engineering and Surveying Dragline Maintenance Engineering A dissertation submitted by Bruce Thomas Jones in fulfilment of the requirements of Courses ENG4111 and 4112 Research Project towards the degree of Bachelor of Engineering (Mechanical) Submitted November, 2007 1 ABSTRACT This research project ‘Dragline Maintenance Engineering’ explores the maintenance strategies for large walking draglines over the past 30 years in the Australian coal industry. Many draglines built since the 1970’s are still original in configuration and utilize original component technology. ie electrical drives, gear configurations. However, there have been many innovative enhancements, configuration changes and upgrading of components The objective is to critically analyze the maintenance strategies, and to determine whether these strategies are still supportive of optimizing the availability and reliability of the draglines. The maintenance strategies associated with dragline maintenance vary, dependent on fleet size and mine conditions; they are aligned with the Risk Based Model. The effectiveness of the maintenance strategy implemented with dragline maintenance is highly dependent on the initial effort demonstrated at the commencement of planning for the mining operation. Mine size, productivity requirements, machinery configuration and economic factors drive the maintenance strategies associated with Dragline Maintenance Engineering. 2 University of Southern Queensland Faculty of Engineering and Surveying ENG4111 -

Mine Safety Technology Task Force Report May 29, 2006

Mine Safety Technology Task Force Report May 29, 2006 Thesis Mine Safety Recommendations Report to the Director of the Office of Miners’ Health, Safety and Training By the West Virginia Mine Safety Technology Task Force As required by West Virginia Code §56-4-4 May 29, 2006 i Mine Safety Technology Task Force Report May 29, 2006 The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Office of Miners’ Health Safety and Training or the State of West Virginia. Questions concerning this report can be directed to the Mine Safety Technology Task Force’s Technical Advisor, Randall Harris, at 304-558-1425 or [email protected] i Mine Safety Technology Task Force Report May 29, 2006 ABSTRACT The Sago and Aracoma disasters and their fourteen deaths, highlighted needed improvements in equipment, capabilities and processes for mine emergency response. The resultant worldwide attention has forever shifted the public’s view of underground mine safety. With the resolve of our government leaders, operators and labor representatives, we have embarked on a mission to improve mine health and safety, thus safeguarding the miners that fuel our nation. The Mine Safety Technology Task Force was charged with the duty of investigating and evaluating options and developing guidelines geared toward protecting the lives of our miners. Special emphasis has been placed on the systems and equipment necessary to sustain those threatened by explosion, fire or other catastrophic events while attempting escape or awaiting rescue. The West Virginia Mine Safety Technology Task Force Report provides a summary of commercial availability and functional and operational capability of SCSR’s, emergency shelters, communications, and tracking along with recommendations regarding implementation, compliance and enforcement. -

<Pea~ Cvistrict ~Iries Chistorical C-Societycltd

<pea~ CVistrict ~iries CHistorical C-SocietyCLtd. NEWSLETTER No 96 OCTOBER 2000 SUMMARY OF DATES FOR YOUR DIARY 22 October U/ground meet - Rochdale Page 2 19 November Ecton Mines Page 3 25 November AGM and Anual Dinner Page 1 22-23 September 2000 NAMHO Field Meet Pagell TO ALL MEMBERS MrN Potter+ ~otice is hereby given that the Twenty Sixth Annual Mr J R Thorpe*(Acting Hon secretary) General Meeting of the Peak District Mines Historical Those whose names are marked (*) are retiring as Society Ltd will be held at 6.00pm on Saturday required by the Articles of Association and are eligible for 25 November 2000 at the Peak District Mining Museum, re-election. Those whose names are marked (+) are Grand Pavilion, Matlock Bath, Derbyshire. retiring and are not eligible for re-election. The Agenda will be distributed at the start of the Fully paid up members of the Society, who are aged meeting. 18 years and over, are invited to nominate Members of the By Order Society (who themselves are fully paid up and who have J Thorpe consented to the nomination) for the vacant positions on Hon Secretary the Committee. Nominations are required for the position of: THE COMPANIES ACT 1985 As required under Article 24 of the Articles of Chairman Association of the Company, the following Directors will Deputy Chairman retire at the Annual General Meeting: Hon Secretary 1. The Hon Secretary (acting) Hon Treasurer 2. The Chairman Hon Recorder 3. The Deputy Chairman Hon Editor 4. The Hon Treasurer Two Ordinary Members 5. The Hon Editor 6. -

An Archaeologist's Guide to Mining Terminology

AUSTRALASIAN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, I5, I997 An Archaeologist'sGuide to Mining Terminology Ited 5as NEVILLEA. RITCHIEAND RAY HOOKER ing Iter the The authors present a glossary of mining terminology commonly used in Australia and New Zealand. The npl definitions and useagescome from historical and contemporary sources and consideration is given to those most frequently encounteredby archaeologists. The terms relate to alluvial mining, hard rock mining, ore rlll9 processing,and coal mining. rng. the \on resultantmodified landforms and relicswhich arelikely to be rnd Thereare literally thousandsof scientificand technicalterms ,of which have been coined to describevarious aspects of the encounteredby or to be of relevanceto field archaeologists processing metalliferousand non-metallic ores. working in mining regionsparticularly in New Zealandbut 1,raS miningand of M. Manyterms have a wide varietyof acceptedmeanings, or their also in the wider Australasia.Significant examples, regional :of meaningshave changed over time. Otherterms which usedto variants,the dateof introductionof technologicalinnovations, trrng be widely used(e.g. those associated with sluice-mining)are and specificallyNew 7na\andusages are also noted.Related Ito seldom used today. The use of some terms is limited to terms and terms which are defined elsewherein the text are nial restrictedmining localities (often arising from Comish or printedin italics. other ethnic mining slang),or they are usedin a sensethat While many of the terms will be familiar to Australian differsfrom thenorm; for instance,Henderson noted a number ella archaeologists,the authorshave not specificallyexamined' v)7 of local variantswhile working in minesat Reeftonon the Australian historical mining literature nor attempted to WestCoast of New T.ealand.l nla.