Groupthink, the News Media, and the Iraq War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Views with Most of the Key Players, Including the President

BOB WOODWARD Legendary Pulitzer Prize-Winning Investigative Journalist Author and Associate Editor, The Washington Post • With Carl Bernstein, Woodward uncovered the Watergate scandal • Author, twelve #1 bestsellers – more than any contemporary nonfiction writer - 18 bestsellers in all • Iconic investigative journalist; winner of nearly every American journalism award, including two Pulitzers • Reporter-historian with an aggressive but fair and non-partisan reputation for digging deep to uncover Washington’s secrets. Gives audiences unvarnished look at Washington politics and leaders • "Woodward has established himself as the best reporter of our time. He may be the best reporter of all time." – Bob Schieffer, CBS News Face the Nation Former CIA director and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates wished he’d recruited Woodward into the CIA, “His ability to get people to talk about stuff they shouldn’t be talking about is just extraordinary and may be unique.” Therein lays the genius of Bob Woodward – a journalistic icon who gained international attention when he and Carl Bernstein broke the deeply disturbing news of the Watergate scandal. The book they wrote - All the President’s Men - won a Pulitzer Prize. Watergate’s theme of secret government is a common thread throughout Woodward’s career that spawned 18 books – all went on to become national bestsellers – 12 of them #1 - more than any other contemporary nonfiction author. In the process Woodward became the ultimate inside man. No one else in political investigative journalism has the clout, respect, and reputation of Woodward. He has a way of getting insiders to open up - both on the record and off the record – in ways that reveal an intimate yet sweeping portrayal of Washington and the budget wrangling, political infighting, how we fight wars, the price of politics, how presidents lead, the homeland security efforts, and so much more. -

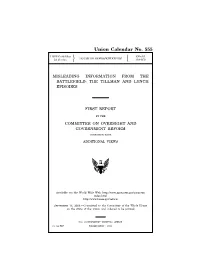

The Tillman and Lynch Episodes

1 Union Calendar No. 555 110TH CONGRESS "!REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 110–858 MISLEADING INFORMATION FROM THE BATTLEFIELD: THE TILLMAN AND LYNCH EPISODES FIRST REPORT BY THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM TOGETHER WITH ADDITIONAL VIEWS Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/ index.html http://www.house.gov/reform SEPTEMBER 16, 2008.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 69–006 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:08 Sep 17, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 C:\DOCS\69006.TXT KATIE PsN: KATIE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HENRY A. WAXMAN, California, Chairman EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York TOM DAVIS, Virginia PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania DAN BURTON, Indiana CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio JOHN L. MICA, Florida DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts TODD RUSSELL PLATTS, Pennsylvania WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri CHRIS CANNON, Utah DIANE E. WATSON, California JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio BRIAN HIGGINS, New York DARRELL E. ISSA, California JOHN A. YARMUTH, Kentucky KENNY MARCHANT, Texas BRUCE L. BRALEY, Iowa LYNN A. WESTMORELAND, Georgia ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina Columbia VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina BETTY MCCOLLUM, Minnesota BRIAN P. BILBRAY, California JIM COOPER, Tennessee BILL SALI, Idaho CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland JIM JORDAN, Ohio PAUL W. -

Sovereignty and Ethical Argument in the Struggle Against State Sponsors of Terrorism

Journal of Military Ethics, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1Á18, 2007 Sovereignty and Ethical Argument in the Struggle against State Sponsors of Terrorism RENE´ E DE NEVERS Department of Public Administration, The Maxwell School, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA ABSTRACT In prosecuting the war on terror, the Bush Administration asserts that the pro- tections inherent in state sovereignty do not apply to state sponsors of terrorism. I examine three elements of normative arguments to assess the administration’s policies. The administration sought to delegitmize terrorism by underscoring the uncivilized nature of terrorist acts. It sought to link the war on terror to efforts to prohibit the spread of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), and to frame the invasion of Iraq as central to this war. Finally, the administration proposed new international standards of behavior by arguing that state sponsors of terrorism should be held accountable for terrorist acts planned on their territory, and by seeking to link the protections against intervention inherent in the sovereignty norm to this behavior. Despite initial support for delegitmizing terrorism, the US attempt to frame the war on terror as linked to WMD and Iraq met with skepticism, and it faced fierce competition from alternate frames with regard to Iraq. Finally, the invasion of Iraq stimulated resistance to US policy on normative grounds, with particular concern about the consequences for the sovereignty norm. KEY WORDS: Norms, Sovereignty, Ethical argument, Terrorism Introduction The war on terror has been the central focus of US foreign policy for over five years. The military components of this war have received the greatest attention, particularly the overthrow of the Taliban government in Afghani- stan and the ousting of Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq. -

Anatomy of a National Security Fiasco: the George W. Bush Administration, Iraq, and Groupthink Phillip G

Anatomy of a National Security Fiasco: The George W. Bush Administration, Iraq, and Groupthink Phillip G. Henderson The Catholic University of America These were people who were selectively picking and then emphasizing pieces of intelligence, I believe, in order to support their larger purpose, which was to bring in a way that they thought possible, to bring democracy to Iraq, and through Iraq to transform the Middle East. I thought that was far-fetched. I didn’t think it was going to happen, but that was their real purpose. They thought that this was going to be a transforming event in history. My frustration is that there was never a national security decision- making process in the administration where people such as me really had a chance to take that on. Richard Haass, Director of Policy Planning at the State Department 2001-2003, Interview with Chris Matthews on “Hardball,” May 6, 2009 In February 2002, one year before the U.S. military intervention in Iraq began, neoconservative writer Ken Adelman predicted that demolishing Saddam Hussein’s regime and liberating Iraq would be a “cakewalk.”1 At a town hall meeting at the Ameri- PHILLIP G. HENDERSON is Associate Professor of Politics at The Catholic University of America. Work on this article was supported by a research grant from the Center for the Study of Statesmanship. 1 Ken Adelman, “Cakewalk in Iraq,” The Washington Post, 13 February 2002, A27. 46 • Volume XXXI, Nos. 1 and 2, 2018 Phillip G. Henderson can air base in Aviano, Italy, on February 7, 2003, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld added that, if force were to be used in Iraq, the war “could last six days, six weeks. -

The Case of Weapons of Mass Destruction at the Outset of the Iraq

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Keck Graduate Institute Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 The aC se of Weapons of Mass Destruction at the Outset of the Iraq War David C. Spiller Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Spiller, David C., "The asC e of Weapons of Mass Destruction at the Outset of the Iraq War" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 54. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/54 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPTER ONE: A WAR OF PREEMPTION The world changed after 9/11. American foreign policy was forced to take a more aggressive stance against potential threats throughout the world. By implementing the Bush doctrine, President George W. Bush sought to reform American foreign policy by waging a preventive war against terrorism and the countries that harbored terrorists. After 9/11 the primary target of the United States was Afghanistan where the Taliban ruled and those responsible for the terrorist attacks were located. By waging war in Afghanistan the Bush administration launched a full assault against terrorism in order to ensure the safety of the United States. Besides Afghanistan, Iraq was another country high on the administration’s priority list due to possible ties to terrorism as well as the potential threat of weapons of mass destruction. The Bush administration identified Iraq as one of the biggest threats to the United States because of the previous history between the two countries. -

'At the Water's Edge: American Politics and the Vietnam War'

H-1960s Eichsteadt on Small, 'At The Water's Edge: American Politics and the Vietnam War' Review published on Thursday, February 1, 2007 Melvin Small. At The Water's Edge: American Politics and the Vietnam War. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee Publisher, 2005. xi + 241 pp. $14.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-56663-647-6; $26.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-56663-593-6. Reviewed by James Eichsteadt (Department of History, Syracuse University) Published on H-1960s (February, 2007) Even though politics and partisanship supposedly stop "at the water's edge," this was not the case during the Vietnam War. Domestic debates and political pressure, argues historian Melvin Small, not only occurred in abundance during the war, they influenced American policymakers. Small, the nation's pre-eminent scholar on the United States during the Vietnam War era,[1] provides readers with a brisk and well-told account of the interconnectedness between events in Southeast Asia and the United States. While most of the study deals with the effect of the war on domestic politics, particularly those of the presidential variety, there are several examples which show the impact political pressure had on foreign-policy decisions. Small points out that since it would be "unseemly" for American leaders to admit they considered domestic factors when formulating plans related to national security, direct evidence of such deliberations in archival documents or in memoirs is rare. But by reading "between the lines," as Small puts it, he shows how concerns over poll numbers and upcoming elections frequently influenced decisions (p. ix). Small is sensitive to not portray every foreign-policy decision as being solely dictated by domestic electoral events, and he avoids being unduly cynical towards politicians concerned with political self-preservation. -

The Unipole in Twilight: American Strategy from 9/11 to the Present

The Unipole in Twilight American Strategy from 9/11 to the Present ✦ JUSTIN LOGAN oreign policy in the United States is like polo: almost entirely an elite sport. The issue rarely figures in national elections. The country is so secure that F foreign policy does not affect voters enough to care much. No country is going to annex Hawaii or Maine, so voters are mostly rationally ignorant of the subject. The costs of wars are defrayed through debt, deficits, and the fact that the dying and dismemberment happens in other people’s countries. Moreover, the dying and dismemberment of Americans are contained in an all-volunteer force that is powerfully socialized to suffer in silence.1 Unlike on abortion, the environment, or taxes, elites in both parties mostly agree on national security. Given rational igno- rance among the public and general consensus among elites, voters rarely hear seri- ous debates about national-security policy (Friedman and Logan 2016). Their views are mostly incoherent and weakly held. The terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001 (9/11) raised the salience of foreign policy. They rocketed President George W. Bush from 51 to 90 percent popularity in the span of fourteen days (Gallup News n.d.). Bush used the wave of approval to pursue an expansive war on terrorism. The United States invaded Afghanistan in October and began planning to attack Iraq. Justin Logan is senior fellow at the Cato Institute. 1. On the effects of an all-volunteer force on support for war, see Erikson and Stoker 2011 as well as Horowitz and Levendusky 2011. -

President Bush and the Invasion of Iraq: Presidential Leadership and Thwarted Goals

From James McCormick, ed., The Domestic Sources of American Foreign Policy, 6th ed. (Roman & Littlefield, 2018), pp. 361-380. President Bush and the Invasion of Iraq: Presidential Leadership and Thwarted Goals James P. Pfiffner George Mason University The 2003 Iraq War is a case study in winning the military battle but losing the war. President George W. Bush demonstrated impressive political skills in taking the country to war, despite the reservations of former generals, members of his father’s administration and the doubts of contemporary military leaders. But President Bush’s political victory in taking the country to war and the quick military defeat of Saddam’s army were undercut by a long post-war insurgency in Iraq, the rise of Iran’s influence in the Middle East, and the establishment of ISIS in a broken Iraq. This case study will examine President Bush’s campaign for war, his use of intelligence to make his case, and the longer-term consequences of the war. Many factors determine a decision to go to war, and in the United States, the personality and character of the president as leader of the country and commander in chief of the armed forces, are particularly important. To be sure, Congress is constitutionally the institution that must “declare war,” but political and governmental dynamics most often favor the president. The president has the advantage of being a single decision maker directing the many bureaucracies that gather intelligence and prepare for war. Virtually all intelligence available to Congress originates in executive branch agencies. Publicly, the president can command the attention of the media and strongly shape public perceptions of the national security situation of the United States. -

Emerging from the Shadows: Vice Presidential Influence in the Modern Era

EMERGING FROM THE SHADOWS: VICE PRESIDENTIAL INFLUENCE IN THE MODERN ERA By RICHARD M. YON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Richard M. Yon To Rachel, Reagan, Linda and Ricky ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to thank all the people and organizations that made this dissertation possible. Without their support and guidance, none of this would have materialized. First, I would like to thank the Department of Political Science’s faculty for their mentorship and guidance over the course of my graduate education at the University of Florida. I would also like to thank Suzanne Lawless-Yanchisin for ensuring I met deadlines and successfully maneuvering me through administrative obstacles. A special thank you to my committee (Beth Rosenson, Larry Dodd, Sharon Austin, Robert Watson, and Elizabeth Dale) for standing by me through this long and arduous process. I’d specifically, like to single out my committee chair, Beth Rosenson, who helped me salvage a project when the prospect of finishing seemed elusive, was a voice of reason at a time when all seemed unreasonable, and restored my confidence in my work and helped me put together a plan to successfully achieve all I worked so hard for. I am forever grateful for the countless hours spent reviewing drafts and providing me with unvarnished critiques that only produced a better product. This project would not have been conceived without the journal article I co-authored with Robert Watson on vice presidential selection. -

State of Denial

State of Denial Jacket "INSURGENTS AND TERRORISTS RETAIN THE RESOURCES AND CAPABILITIES TO SUSTAIN AND EVEN INCREASE CURRENT LEVEL OF VIOLENCE THROUGH THE NEXT YEAR." This was the secret Pentagon assessment sent to the White House in May 2006. The forecast of a more violent 2007 in Iraq contradicted the repeated optimistic statements of President Bush, including one, two days earlier, when he said we were at a "turning point" that history would mark as the time "the forces of terror began their long retreat." State of Denial examines how the Bush administration avoided telling the truth about Iraq to the public, to Congress, and often to themselves. Two days after the May report, the Pentagon told Congress, in a report required by law, that the "appeal and motivation for continued violent action will begin to wane in early 2007." In this detailed inside story of a war-torn White House, Bob Woodward reveals how White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card, with the indirect support of other high officials, tried for 18 months to get Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld replaced. The president and Vice President Cheney refused. At the beginning of Bush's second term, Stephen Hadley, who replaced Condoleezza Rice as national security adviser, gave the administration a "D minus" on implementing its policies. A SECRET report to the new Secretary of State Rice from her counselor stated that, nearly two years after the invasion, Iraq was a "failed state." State of Denial reveals that at the urging of Vice President Cheney and Rumsfeld, the most frequent outside visitor and Iraq adviser to President Bush is former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who, haunted still by the loss in Vietnam, emerges as a hidden and potent voice. -

Legislative Branch

The United States Government Manual 2001/2002 Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration VerDate 11-MAY-2000 14:31 Aug 20, 2001 Jkt 188578 PO 00000 Frm 00695 Fmt 6996 Sfmt 6996 D:\GOVMAN\188578.111 APPS10 PsN: 188578 Revised June 1, 2001 Raymond A. Mosley, Director of the Federal Register. John W. Carlin, Archivist of the United States. On the cover: World War-I era American postcard with bald eagle and American flag, postmarked 1917. The bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) is the only eagle unique to North America. Admired for its majestic appearance and self-reliance, it became the national symbol in 1782 when the Second Continental Congress approved the design of the Nation’s official seal. The Great Seal of the United States includes a shield that, according to Secretary Charles Thomson’s journal of the Congress for June 20, 1782, is ‘‘borne on the breast of an American Eagle without any supporters, to denote that the United States of America ought to rely on their own virtue.’’ Although the bald eagle has endured as an American icon, by the 1960s only an estimated 450 nesting pairs remained in the conterminous (lower 48) States. Farmers and ranchers aggressively hunted the bird to protect their livestock. In 1940 Congress passed the Bald Eagle Protection Act which made it illegal to kill, harass, possess without a permit, or sell bald eagles. Still, the population continued to decline, largely due to the introduction of DDT and other pesticides, which contaminated the lakes and streams where the eagle fished. -

European Media Representations of US Foreign Policy Making

Loughborough University Institutional Repository Framing the neocons : European media representations of US foreign policy making This item was submitted to Loughborough University's Institutional Repository by the/an author. Additional Information: • A Doctoral Thesis. Submitted in partial fullment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University. Metadata Record: https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/12167 Publisher: c George Tzogopoulos Please cite the published version. This item was submitted to Loughborough University as a PhD thesis by the author and is made available in the Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ ~~~-~-------~-,---~---",--,------.--------.--.--.--- ....-- ... ~ ....., ~l r. ., ~ ~ ~ f ;~:~: ''-' "'.' ,. --,.~'.J ,] -: ~.. 1 .: .. : ;~ ~ ~ :.; ~"..(~,;;~:;:-;, ~;~ -~.- ~. ,:.:--' ~.-:r:'- -. .....:t·.. _;,;::..... _-.. ~',· .... '~~:J;·-.-'t'.u=-"- :'. ,-". -',";:V." -"" .:_'~ ,l.:.:.. _~.~~...... '~~.-•.:..J;I! ...........~ l J.~,VV j r!~~i\10. - k - - ~ ,I t ~ ~ ~."7'1.~_~~_\W.. .._.. i ....~ r __ ~.."'"-"_~I IDat3 I !':r-,.:; ,'v·_- ••. "-'.-.:..:~.~..v..... - •.".,,'l._:.: __~-,:.-:.: ... -;-' .,._y~·.~.'"-r.:', ..-._~·>;....:.T .• "-,-~;:::,~;.:: ... ~..:.;.:~...I.~~Cl<C-~~ 'Framing the Neocons: European Media Representations of US Foreign Policy-Making' by George Tzogopoulos A Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial