The Path to Intractability the Path to Ron E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

Shots Were Fired | Norient.Com 1 Oct 2021 02:06:01 Shots Were Fired MIXTAPE by Bernard Clarke

Shots Were Fired | norient.com 1 Oct 2021 02:06:01 Shots Were Fired MIXTAPE by Bernard Clarke War is the biggest and most horrible drama of human kind. Yet the noises of war – everything from swords clanging to modern machine guns and bombs – have fascinated musicians and composers for centuries. For his mix «shots were fired» for the section «war» from the Norient exhibition Seismographic Sounds the Irish radio journalist Bernard Clarke combined radio news samples with musically deconstructed war sounds. «shots were fired» is a deeply personal response to a tragedy and farce played out in a Paris dripping with blood and a media whipping up a frenzy; to and of the forgotten victims in France and around the world; and of and to the so-called world leaders who seized on this outrage for a media opportunity, a «selfie». Western societies are not the havens of rationalism that they often proclaim themselves to be. The West is a polychromatic space, in which both freedom of thought and tightly regulated speech exist, and in which disavowals of deadly violence happen at the same time as clandestine torture. And yet, at moments when Western societies consider themselves under attack, the discourse is quickly dominated by an ahistorical fantasy of long- suffering fortitude in the face of provocation. Yet European and American history are so strongly marked by efforts to control speech that the persecution of rebellious thought stands as a bedrock of these societies. Witch burnings, heresy trials, and the untiring work of the Inquisition shaped Europe, and these ideas extended into American history as well and took on American modes, from the breaking of slaves to the genocide of American Indians to censuring of critics of «Operation Iraqi Freedom». -

Egyptian Foreign Policy (Special Reference After the 25Th of January Revolution)

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE DERECHO INTERNACIONAL PÚBLICO Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES TESIS DOCTORAL Egyptian foreign policy (special reference after The 25th of January Revolution) MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTORA PRESENTADA POR Rania Ahmed Hemaid DIRECTOR Najib Abu-Warda Madrid, 2018 © Rania Ahmed Hemaid, 2017 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Políticas Y Socioligía Departamento de Derecho Internacional Público y Relaciones Internacionales Doctoral Program Political Sciences PHD dissertation Egyptian Foreign Policy (Special Reference after The 25th of January Revolution) POLÍTICA EXTERIOR EGIPCIA (ESPECIAL REFERENCIA DESPUÉS DE LA REVOLUCIÓN DEL 25 DE ENERO) Elaborated by Rania Ahmed Hemaid Under the Supervision of Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda Professor of International Relations in the Faculty of Information Sciences, Complutense University of Madrid Madrid, 2017 Ph.D. Dissertation Presented to the Complutense University of Madrid for obtaining the doctoral degree in Political Science by Ms. Rania Ahmed Hemaid, under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda Professor of International Relations, Faculty of Information Sciences, Complutense University of Madrid. University: Complutense University of Madrid. Department: International Public Law and International Relations (International Studies). Program: Doctorate in Political Science. Director: Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda. Academic Year: 2017 Madrid, 2017 DEDICATION Dedication To my dearest parents may god rest their souls in peace and to my only family my sister whom without her support and love I would not have conducted this piece of work ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Prof. Dr. Najib Abu- Warda for the continuous support of my Ph.D. -

Sudan: International Dimensions to the State and Its Crisis

crisis states research centre OCCASIONAL PAPERS Occasional Paper no. 3 Sudan: international dimensions to the state and its crisis Alex de Waal Social Science Research Council April 2007 ISSN 1753 3082 (online) Copyright © Alex de Waal, 2007 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Occasional Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Occasional Paper, or any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE 1 Crisis States Research Centre Sudan: International Dimensions to the State and its Crisis Alex de Waal Social Science Research Council Overview This paper follows on from the associated essay, “Sudan: What Kind of State? What Kind of Crisis?”1 which concluded that the two dominant characteristics of the Sudanese state are (a) the extreme economic and political inequality between a hyper-dominant centre and peripheries that are weak and fragmented and (b) the failure of any single group or faction within the centre to exercise effective control over the institutions of the state, but who nonetheless can collectively stay in power because of their disproportionate resources. -

Trinity and the Rising Commemorating the 1916 Centenary Trinity and the Rising Commemorating the 1916 Centenary

Trinity and the Rising Commemorating the 1916 centenary Trinity and the Rising Commemorating the 1916 centenary Soldier and poet, Francis Ledwidge This booklet was produced by Katie Strickland Byrne in the Office of Public Affairs and Communications. TRInITy and The RIsIng CommemoRaTIng The 1916 CenTenaRy Contents John Boland 02 Introduction by the dean of Research eunan o’halpin 04 Lest we forget: Trinity College and the decade of Commemorations Jane ohlmeyer 07 an unstoppable process Ruth Barton 14 screening 1916 davis Coakley 16 small town – high walls estelle gittins 19 ‘all changed, changed utterly’: Commemorating the 1916 easter Rising at the Library of Trinity College dublin sarah smyth 21 Translations Iggy mcgovern 23 alliterations gerald dawe 24 an affirming Flame andrew o’Connell 26 Radio Rising Caoimhe ní Lochlainn 29 Trinity’s public engagement and media interest Patrick geoghegan 31 Vision for the future – appeal to the past page 01 TRInITy and The RIsIng CommemoRaTIng The 1916 CenTenaRy Introduction by the dean of Research Collected in this book, are reflections from leading academics and staff across our community. Eunan O’Halpin from the School of History outlines some of the events hosted by Trinity in the years leading up to 2016 that sought to look beyond the confines of the Rising and to place it in a broader historical context. Jane Ohlmeyer, director of the Trinity Long Room Hub Arts and Humanities Research Institute (TLRH), traces elements of this broader historical context in her analysis of how the Rising impacted on the British Empire, paying particular attention to how it was received in India, and notes the current day issues surrounding the fate of Northern Ireland in the wake of the recent Brexit vote. -

News and Notes 1980-1989

NEWS AND NOTES FROM The Prince George's County Historical Society Vol. VIII, no. 1 January 1980 The New Year's Program There will be no meetings of the Prince George's County Historical Society in January or February. The 1980 meeting program will begin with the March meeting on the second Saturday of that month. Public Forum on Historic Preservation The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission will sponsor a public forum on the future of historic preservation in Prince George's County on Thursday, January 10, at the Parks and Recreation Building, 6600 Kenilworth Avenue, in Riverdale. This forum, is the first step in the process of drafting a county Historic Sites and Districts Plan by the commission. (See next article). The purpose of the forum is to receive public testimony on historic preservation in Prince George's county. Among the questions to be addressed are these: How important should historic preservation, restoration, rehabilitation, and revitalization be to Prince George's County? What should the objectives and priorities of a historic sites and districts plan be? What should be the relative roles of County government and private enterprise be in historic preservation and restoration? To what extent should the destruction of historic landmarks be regulated and their restoration or preservation subsidized? How should historic preservation relate to tourism, economic development, and revitalization? Where should the responsibility rest for making determinations about the relative merits of preserving and restoring individual sites? Members of the Historical Society, as well as others interested in historic preservation and its impact on county life, are invited to attend and, if they like, to testify. -

Republic of the Sudan Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Republic of the Sudan Ministry of Foreign Affairs DECLARATION BY THE MINISTRY OF FOREIN AFFAIRS OF THE REPUBLIC OF THESLIDAN Pursuant to the republican decree no (148) of 2017 dated 2/3/2017 on the demarcation of the maritime baseline of the Republic of the Sudan on the Red Sea, and which was deposited with UN Secretary General on April 7th 2017, With reference to the declaration of the Government of the Sudan on its objection and rejection of the declaration of the Arab republic of Egypt dated 2nd of May 2017, on the demarcation of it's maritime boundaries, including coordinates which include the maritime zone of the Sudanese Halaeb Triangle, as part of its borders, The Government of the Sudan declares it objection and rejection to what is known as the Agreement on the demarcation of maritime boundaries between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Arab Republic of Egypt signed on April 8th 2016, and which was deposited at the UN records (Treaty Section.. volume 5477), The Government of the Sudan, while objecting to the agreement, reaffirms its rejection to all that the agreement includes on the Delimitation of the Egyptian maritime boundaries which include coordinates of maritime areas that are an integral part of the maritime boundaries of the Sudanese Halaeb Triangle , in consonance with the Sudan's complaint deposited with the UNSC since 1958,and which the Sudan has been renewing annually, and all the correspondences between the Government of the Sudan and the UN Secretary General and the UNSC, on the repeated attacks on the land and people of the Haleaeb Triangle by the Egyptian Occupying Authorities. -

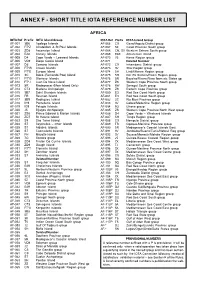

Short Title Iota Reference Number List

RSGB IOTA DIRECTORY ANNEX F - SHORT TITLE IOTA REFERENCE NUMBER LIST AFRICA IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group AF-001 3B6 Agalega Islands AF-066 C9 Gaza/Maputo District group AF-002 FT*Z Amsterdam & St Paul Islands AF-067 5Z Coast Province South group AF-003 ZD8 Ascension Island AF-068 CN, S0 Western Sahara South group AF-004 EA8 Canary Islands AF-069 EA9 Alhucemas Island AF-005 D4 Cape Verde – Leeward Islands AF-070 V5 Karas Region group AF-006 VQ9 Diego Garcia Island AF-071 Deleted Number AF-007 D6 Comoro Islands AF-072 C9 Inhambane District group AF-008 FT*W Crozet Islands AF-073 3V Sfax Region group AF-009 FT*E Europa Island AF-074 5H Lindi/Mtwara Region group AF-010 3C Bioco (Fernando Poo) Island AF-075 5H Dar Es Salaam/Pwani Region group AF-011 FT*G Glorioso Islands AF-076 5N Bayelsa/Rivers/Akwa Ibom etc States gp AF-012 FT*J Juan De Nova Island AF-077 ZS Western Cape Province South group AF-013 5R Madagascar (Main Island Only) AF-078 6W Senegal South group AF-014 CT3 Madeira Archipelago AF-079 ZS Eastern Cape Province group AF-015 3B7 Saint Brandon Islands AF-080 E3 Red Sea Coast North group AF-016 FR Reunion Island AF-081 E3 Red Sea Coast South group AF-017 3B9 Rodrigues Island AF-082 3C Rio Muni Province group AF-018 IH9 Pantelleria Island AF-083 3V Gabes/Medenine Region group AF-019 IG9 Pelagie Islands AF-084 9G Ghana group AF-020 J5 Bijagos Archipelago AF-085 ZS Western Cape Province North West group AF-021 ZS8 Prince Edward & Marion Islands AF-086 D4 Cape Verde – Windward Islands AF-022 ZD7 -

New Issues in Refugee Research

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Research Paper No. 254 Refugees and the Rashaida: human smuggling and trafficking from Eritrea to Sudan and Egypt Rachel Humphris Ph.D student COMPAS University of Oxford Email: [email protected] March 2013 Policy Development and Evaluation Service Policy Development and Evaluation Service United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees P.O. Box 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates, as well as external researchers, to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction Eritreans have been seeking asylum in east Sudan for more than four decades and the region now hosts more than 100,000 refugees1. East Sudan has also become a key transit region for those fleeing Eritrea. One route, from East Sudan to Egypt, the Sinai desert and Israel has gained increasing attention. According to UNHCR statistics, the number of Eritreans crossing the border from Sinai to Israel has increased from 1,348 in 2006 to 17,175 in 2011. Coupled with this dramatic growth in numbers, the conditions on this route have caused great concern. Testimonies from Eritreans have increasingly referred to kidnapping, torture and extortion at the hands of human smugglers and traffickers. The smuggling route from Eritrea to Israel is long, complex and involves many different actors. As such, it cannot be examined in its entirety in a single paper. -

Spring 2013 L E B R a T I N G

Sisters of St. Joseph of Boston Connecting Neighbor with Neighbor and Neighbor with God VOL 21#3 e Spring 2013 l e b r a t i n g 140 Y e a r Office of Mission Advancement s 1873 - 2013 www.csjboston.org From the President Office of Mission Advancement s I gaze out my office window a long- standing maple tree is budding forth with Mission Statement wisps of spring green. Natural beauty The Office of Mission Advancement Ais emerging to give us new life and new hope, of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Boston something much needed in our city and world fully supports the mission and after the senseless tragedy of the Boston Marathon ministries of the Sisters. We raise bombing. funds to support all present and future Connecting ministries and to continue the legacy of As this edition of is one of the Congregation. honoring and remembering, we place the names We also provide funds through of Martin Richard, Krystal Campbell, and Lu Lingzi along with MIT police donor generosity to care for our elderly officer, Sean Collier, in our list of remembrances. And we humbly honor the and infirm Sisters. All donations enable survivors and all who exhibited selfless care, concern, and love in the midst of the Congregation to strengthen its mind-boggling mayhem. mission of unity and reconciliation “Humanity is better than this. We are a resilient, adaptable species with among the people it serves. We thank a propensity towards community and kindness. .Go outside today and our friends and benefactors who recognize the true nature of humanity. -

2008 in the National Library of Ireland

Page 1 of 48 2008 in the National Library of Ireland Our Mission To collect, preserve, promote and make accessible the documentary and intellectual records of the life of Ireland and to contribute to the provision of access to the larger universe of recorded knowledge. Page 2 of 48 Report of the Board of the National Library of Ireland For the year ended 31 December 2008 To the Minister for Arts, Sport & Tourism pursuant to section 36 of the National Cultural Institutions Act 1997. Published by National Library of Ireland ISSN 2009-020X (c) Board of the National Library of Ireland, 2009 Page 3 of 48 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD OVERVIEW 2008 Progress towards: Strategic aims and objectives Developing and safeguarding collections Quality service delivery Achieving outreach, collaboration and synergy Improving the physical infrastructure Developing staff Developing the organisation BOARD AND COMMITTEES OF THE BOARD APPENDICES: Appendix 1: Thanks to our sponsors and donors Appendix 2: National Library of Ireland Society Appendix 3: Visitor numbers and other statistics Appendix 4: Collaborative Partnerships in 2008 Page 4 of 48 Chairman’s Statement As Chairman of the Board of the National Library of Ireland I am pleased to present this, the Board’s fourth annual report, which summarises significant developments in the Library in 2008. The year marked a period of consolidation, with continuing investment in acquisitions and in digitisation and related IT infrastructural initiatives. Services continued to be developed and improved, and a wide range of events and activities took place in the Library. Considerable progress was made during the year in achieving many of the goals and objectives set out in the Library’s Strategic Plan 2008–2010. -

Calais Maine Families : They Came and They Went Thelma Eye Brooks

Maine State Library Digital Maine Calais Books Calais, Maine 2002 Calais Maine Families : They Came and They Went Thelma Eye Brooks Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/calais_books Recommended Citation Brooks, Thelma Eye, "Calais Maine Families : They aC me and They eW nt" (2002). Calais Books. 2. https://digitalmaine.com/calais_books/2 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Calais, Maine at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Calais Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CALAIS MAINE FAMILIES THEY CAME AND THEY WENT Thelma Eye Brooks HERITAGE BOOKS, INC. Copyright 2002 Thelma Eye Brooks Published 2002 by HERITAGE BOOKS, INC. 1540E Pointer Ridge Place Bowie, Maryland 20716 1-800-398-7709 www.heritagebooks.com ISBN 0-7884-2135-2 A Complete Catalog Listing Hundreds of Titles On History, Genealogy, and Americana Available Free Upon Request " *'4 - ' ' CALAIS, MAINE FAMILIES THEY CAME AND THEY WENT The families included in this book are the families listed in Book I of Calais Vital Records. I have placed the names in alphabetical order with the page number of the original record following the name of the head of family. The goal of this project was to find three generations of each family - one back from the head of the family and his wife, and the children and their spouses. INTRODUCTION In 1820 in the Calais census there were 61 males between 1 6 -2 6 years living in 64 households. By 1830 there were 399 males between 21 & 30 years living in 225 households.