Nawab Viqar-Ul-Mulk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: a Case Study of the Punjab

Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: A Case Study of the Punjab A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY By Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan 2016 Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my individual research, and that it has not been submitted concurrently to any other university for any other degree. _____________________ Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD Approval for Thesis Submission Dated: 2016 I hereby recommend the thesis prepared under my supervision by Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari, entitled “Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: A Case Study of the Punjab” in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. __________________________ Dr. Razia Sultana Supervisor DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD Dated: 2016 FINAL APPROVAL This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari, entitled “Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: A Case Study of the Punjab” and it is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant acceptance by the Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. _ ____________________ -

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: a Historical Analysis

Bulletin of Education and Research December 2019, Vol. 41, No. 3 pp. 1-18 Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: A Historical Analysis Maqbool Ahmad Awan* __________________________________________________________________ Abstract This article highlightsthe vibrant role of the Muslim Anjumans in activating the educational revival in the colonial Punjab. The latter half of the 19th century, particularly the decade 1880- 1890, witnessed the birth of several Muslim Anjumans (societies) in the Punjab province. These were, in fact, a product of growing political consciousness and desire for collective efforts for the community-betterment. The Muslims, in other provinces, were lagging behind in education and other avenues of material prosperity. Their social conditions were also far from being satisfactory. Religion too had become a collection of rites and superstitions and an obstacle for their educational progress. During the same period, they also faced a grievous threat from the increasing proselytizing activities of the Christian Missionary societies and the growing economic prosperity of the Hindus who by virtue of their advancement in education, commerce and public services, were emerging as a dominant community in the province. The Anjumans rescued the Muslim youth from the verge of what then seemed imminent doom of ignorance by establishing schools and madrassas in almost all cities of the Punjab. The focus of these Anjumans was on both secular and religious education, which was advocated equally for both genders. Their trained scholars confronted the anti-Islamic activities of the Christian missionaries. The educational development of the Muslims in the Colonial Punjab owes much to these Anjumans. -

Zay Khay Sheen, Aligarh's Purdah-Nashin Poet

1 Zay Khay Sheen, Aligarh’s Purdah-Nashin Poet Gail Minault* Zay Khay Sheen, or Zahida Khatun Sherwani (1894-1922),1 was the younger daughter of Nawab Sir Muzammilullah Khan Sherwani, Rais of Bhikampur in the Aligarh district of North India.2 Sir Muzammilullah (1865-1938) was an important figure in the Aligarh movement. A follower of Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan, he was a leading member of the Board of Trustees of Aligarh College, a champion of turning Aligarh College into a University, and politically loyal to the British connection. He was also a skillful poet in Persian, and had a string of alphabetical honors following his title as Khan Bahadur: LLD, KCIE, OBE, etc.3 The Sherwani clan of Aligarh district was distinguished in educational circles and produced a number of important figures, Habibur Rahman Khan Sherwani, Nawab Habib Yar Jung, was an Islamic scholar and an official in Hyderabad. Harun Khan Sherwani was a well-known historian of the Deccan (his wife is the biographer of Z-Kh-Sh). The clan had two main branches, the lineage of Bhikampur and that of Datauli, and practiced cousin marriage to an almost exclusive degree. The family tree presents a bewildering array of interlocking relationships.4 1* Gail Minault is a Professor of History and Asian Studies at the University of Texas, Austin, Texas, USA. There are two basic sources about Z-Kh-Sh, a biography written by her cousin: Anisa Harun Begam Sherwani, Hayat-i-Z-Kh-Sh (Hyderabad: Privately Published, 1954); and her collected poems: Z-Kh-Sh [Zahida Khatun Sherwani], Firdaus-i-Takhayyul (Lahore: Dar ul Isha’iat-i-Punjab, 1941). -

Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan

Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema Maqsudul Hasan Nuri Muneer Mahmud Khalid Hussain Editors ASIA PAPER November 2008 Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan Papers from a Conference Organized by Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and the Institute of Security and Development Policy (ISDP) in Islamabad, October 29-30, 2007 Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema Maqsudul Hasan Nuri Muneer Mahmud Khalid Hussain Editors © Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Islamabad Policy Research Institute House no.2, Street no.15, Margalla Road, Sector F-7/2, Islamabad, Pakistan www.isdp.eu; www.ipripak.org "Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan" is an Asia Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. Through its Silk Road Studies Program, the Institute runs a joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. The Institute is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This report is published by the Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and is issued in the Asia Paper Series with the permission of IPRI. -

The Khilafat Movement in India 1919-1924

THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR T AAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 62 THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 A. C. NIEMEIJER THE HAGUE - MAR TINUS NIJHOFF 1972 I.S.B.N.90.247.1334.X PREFACE The first incentive to write this book originated from a post-graduate course in Asian history which the University of Amsterdam organized in 1966. I am happy to acknowledge that the university where I received my training in the period from 1933 to 1940 also provided the stimulus for its final completion. I am greatly indebted to the personal interest taken in my studies by professor Dr. W. F. Wertheim and Dr. J. M. Pluvier. Without their encouragement, their critical observations and their advice the result would certainly have been of less value than it may be now. The same applies to Mrs. Dr. S. C. L. Vreede-de Stuers, who was prevented only by ill-health from playing a more active role in the last phase of preparation of this thesis. I am also grateful to professor Dr. G. F. Pijper who was kind enough to read the second chapter of my book and gave me valuable advice. Beside this personal and scholarly help I am indebted for assistance of a more technical character to the staff of the India Office Library and the India Office Records, and also to the staff of the Public Record Office, who were invariably kind and helpful in guiding a foreigner through the intricacies of their libraries and archives. -

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

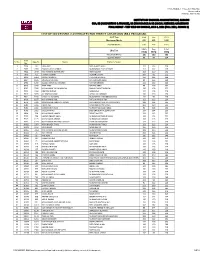

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

Mcqs of Past Papers Pakistan Affairs

Agha Zuhaib Khan MCQS OF PAST PAPERS PAKISTAN AFFAIRS 1). Sir syed ahmed khan advocated the inclusion of Indians in Legislative Council in his famous book, Causes of the Indian Revolt, as early as: a) 1850 b) 1860 c) 1870 d) None of these 2). Who repeatedly refers to Sir Syed as Father of Muslim India and Father of Modern Muslim India: a) Hali b) Abdul Qadir c) Ch. Khaliquz Zaman d) None of these 3). Military strength of East India Company and the Financial Support of Jaggat Seth of Murshidabad gave birth to events at: a) Plassey b) Panipat c) None of these 4). Clive in one of his Gazettes made it mandatory that no Muslim shall be given an employment higher than that of chaprasy or a junior clerk has recorded by: a) Majumdar b) Hasan Isphani c) Karamat Ali d) None of these 5). The renowned author of the Spirit of Islam and a Short History of the Saracens was: a) Shiblee b) Nawab Mohsin c) None of these ( Syed Ameer Ali) 1 www.css2012.co.nr www.facebook.com/css2012 Agha Zuhaib Khan 6). Nawab Sir Salimullah Khan was President of Bengal Musilm Leage in: a) 1903 b) 1913 c) 1923 d) None of these (1912) 7). The first issue of Maualana Abul Kalam Azads „Al Hilal‟ came out on 13 July: a) 1912 b) 1922 c) 1932 d) None of these 8). At the annual session of Anjuman Hamayat Islam in 1911 Iqbal‟s poem was recited, poetically called: a) Sham-o-Shahr b) Shikwa c) Jawab-i-Shikwa d) None of these 9). -

KPK Assembly

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN NOTIFICATION Islamabad the 5th June, 2013 No.F.2(43)/2013-Cord.- In pursuance of the provisions of sub-section (3A) and sub-section (4) of Section 42 of the Representation of the People Act, 1976 (Act No. LXXXV of 1976), the Election Commission of Pakistan hereby publishes the names of candidates returned to the Provincial Assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa from the constituencies mentioned below against the name of each candidate: Sl. Names of the No. of Total No. Total votes Name of the No Contesting valid votes of rejected polled in the candidate Candidates secured by the votes constituency declared Constesting elected with Party Affiliation candidates 1. 2. 3. 4. 5 6 PK-1 PESHAWAR-I 1 Ajmal Khan 227 2 Ghazanfar Bilour 4782 3 M. Zakir Shah 1063 4 Irfan Ullah 72 5 Gul Jan 16 6 Mosab Mukhtar 29 7 Zia Ullah Afridi 22932 Zia Ullah Afridi (Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf) 8 Muhammad Adeel 1571 9 Hassan Khan 12 10 Ashfaq Ahmad 334 11 Bahrullah Khan 5156 12 Mir Alam Khan 26 13 Zahoor Khan 21 14 Akhunzada Irfan Ullah Shah 4819 15 Muhammad Shah Zeb 252 16 Muhammad Younas 14 17 Saif Ullah 249 18 Muhammad Nadeem 178 19 Muhammad Nadeem 234 20 Muhammad Akbar Khan 4376 21 Abdur Rahim Khan 6 22 Muhammad Nadeem 6907 23 Yasar Farid 20 24 Zafar Ullah 28 25 Younas Khan 63 26 Malik Parvez Khan 55 27 Abdul Aziz Khan 198 Total 53640 811 54451 PK-2 PESHAWAR-II 1 Hidayat Ullah Khan Afridi Advocat 56 2 Sardar Naeem 305 3 Shamsur Rehman Safi 86 4 Pir Abdur Rehman 85 5 Saeed Ur Rehman Safi 2782 6 Shahid Noor 74 7 Shafqat Hussain Durrani 125 8 Siraj Ud Din 2453 9 Malik Ghulam Mustafa 6273 1 1. -

I Leaders of Pakistan Movement, Vol.I

NIHCR Leadersof PakistanMovement-I Editedby Dr.SajidMehmoodAwan Dr.SyedUmarHayat National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad - Pakistan 2018 Leaders of Pakistan Movement Papers Presented at the Two-Day International Conference, April 7-8, 2008 Vol.I (English Papers) Sajid Mahmood Awan Syed Umar Hayat (Eds.) National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad – Pakistan 2018 Leaders of Pakistan Movement NIHCR Publication No.200 Copyright 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the Director, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to NIHCR at the address below: National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, New Campus, Quaid-i-Azam University P.O. Box 1230, Islamabad-44000. Tel: +92-51-2896153-54; Fax: +92-51-2896152 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: www.nihcr.edu.pk Published by Muhammad Munir Khawar, Publication Officer Formatted by \ Title by Khalid Mahmood \ Zahid Imran Printed at M/s. Roohani Art Press, Sohan, Express Way, Islamabad Price: Pakistan Rs. 600/- SAARC countries: Rs. 1000/- ISBN: 978-969-415-132-8 Other countries: US$ 15/- Disclaimer: Opinions and views expressed in the papers are those of the contributors and should not be attributed to the NIHCR in any way. Contents Preface vii Foreword ix Introduction xi Paper # Title Author Page # 1. -

Muslim Urban Politics in Colonial Punjab: Majlis-I-Ahrar's Early Activism

235 Samina Awan: Muslim Urban Politics Muslim Urban Politics in Colonial Punjab: Majlis-i-Ahrar’s Early Activism Samina Awan Allama Iqbal Open University, Pakistan ________________________________________________________________ The British annexed Punjab in 1849, and established a new system of administration in form and spirit. They also introduced western education, canal colonies and a modern system of transportation, which had its impact on the urban population. In rural Punjab they collaborated with the landlords and feudal elite to get their support in strengthening the province as ‘grain basket’ for the British Army. The Majlis-i-Ahrar-i-Islam(hereafter MAI) was an urban Muslim organisation, comprised of ex-Khilafatists, trained in agitational politics during the period 1919-1929, many of whom were ex-Congrssites. Ahrar leaders split with the INC over the issue of the Nehru Report in 1929. Soon after the formation of the new party, they decided to participate in INC-led civil disobedience movement of 1930 and were interred in large numbers. The MAI’s platform was based on a united India, but one, which was free from imperial control, anti-feudal, with less economic disparities and had an Islamic system for the Muslims of India. _______________________________________________________________ Introduction A number of religio-political movements emerged from Punjab during the first half of the twentieth century. A study of the history, politics and social structure of Punjab is necessary in order to understand these movements. The Majlis-i- Ahrar-i-Islam (MAI) was founded in 1929 in Lahore, and reflected a unique blend of religion and politics in the multi-cultural province of Punjab in British India. -

Khilafat Movement and the Province of Sindh

KHILAFAT MOVEMENT AND THE PROVINCE OF SINDH Dr. Nasreen Afzal* KHILAFAT MOVEMENT AND THE PROVINCE OF SINDH ABSTRACT The Khilafat Movement started by the Muslims of India is directly related to the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire of Turkey, the only Muslim power of the world during the twentieth century, at the hands of different European nations and particularly against the hostile attitude of Britain towards Turkey . Like other areas of India Muslim s of Sindh played significant role in this movement. This article deals with the different efforts of Muslims of Sindh along with the Muslims of other areas for saving khlifat. Key words: Non violence non co-operation movement, Congress, Fatwas, Hijrat * Assistant Professor, Department of History , University of Karachi, Pakistan 51 Jhss, Vol. 1, No.1 , January to June 2010 The institution of Khilafat began after the death of Holy Prophet (P.B.U.H) in 632 AD when Hazrat Abu Bakr, who was the successor of the Holy Prophet, adopted the title of Khaltfatu-Rasool-i-illah , successor of Prophet of God. 1 The successor of Hazrat Abu Bakr, Hazrat Umar simplified the title to Khaltfah 2 and the Caliph (An English version of Khaltfah ) became temporal and spiritual head of the entire Muslims of the World. The first four caliphs were all selected democratically. However, after the death of Hazrat Ali, Amir Mu’awiyah laid down the foundation of Umayyad Dynasty, which changed the nature of Khilafat from democratic institution to monarchy. Umayyads and the rulers of the successive Muslim dynasties such as Abbasids, Fatimid (Egypt) and finally Ottomans (Turkey) continued to use the title of Caliph as used by four early Caliphs and further strengthening the institution of Khilafat, as a result Caliph became the symbolic head of the Muslim rule, even outside of Arabia.