“An Absurdly Quiet Spot”: the Spatialjustice Ofww1 Fraternizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Des Films Suggérés

Des films suggérés Films animés -Persepolis (bio d’une fille iranienne) Films comiques -L’Auberge espagnole (int’l college student roommates) Science Fiction/Fantaisie -Les poupées russes (sequel) -City of Lost Children -Les compères (who’s the real father?) -Delicatessen -3 hommes & un couffin (original of 3 Men & a baby) -Le placard (The Closet—man pretends to be gay) Films Spirituels / Réligieux -La chèvre -Thérèse (story of Ste Thérèse) -Les visiteurs (medieval knights travel to future) -Jésus de Montréal (Passion play turns real) -anything with Fernandel (noir & blanc) -My wife is an Actress (husband jealous of wife’s costars) Films dramatiques -Dîner des cons (Who’s really the jerk?) -Camille Claudel (true tragic story of great artist) -Mon oncle (weird comedy, not much talking) -Toto le héros (man’s whole life consumed by jealousy) -Jean de Florette* (city man moves to inherited farm w/family) Comédies romantiques -Manon des sources* (sequel, concentrates on daughter ) -Après vous (man helps down & out friend) -A Self-Made Hero (insecure guy totally invents life & army career) -Maman, il y a un homme dans ton lit! -Le Huitième Jour (friendship between 2 guys, 1 handicapped, 1 sad) -Amélie (girl finds amazing ways to right wrongs!) -Bleu (woman makes new life after tragic car accident) -Paper wedding (Green Card en français) -Blanc -The Valet (car parker pretends to be girl’s copain) -Rouge (romantic meetings--coincidence or destiny?) -A la mode (rags to riches story) -Est-Oeust (family returns to Russia w/ horrible consequences) -

The Phenomenological Aesthetics of the French Action Film

Les Sensations fortes: The phenomenological aesthetics of the French action film DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alexander Roesch Graduate Program in French and Italian The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Flinn, Advisor Patrick Bray Dana Renga Copyrighted by Matthew Alexander Roesch 2017 Abstract This dissertation treats les sensations fortes, or “thrills”, that can be accessed through the experience of viewing a French action film. Throughout the last few decades, French cinema has produced an increasing number of “genre” films, a trend that is remarked by the appearance of more generic variety and the increased labeling of these films – as generic variety – in France. Regardless of the critical or even public support for these projects, these films engage in a spectatorial experience that is unique to the action genre. But how do these films accomplish their experiential phenomenology? Starting with the appearance of Luc Besson in the 1980s, and following with the increased hybrid mixing of the genre with other popular genres, as well as the recurrence of sequels in the 2000s and 2010s, action films portray a growing emphasis on the importance of the film experience and its relation to everyday life. Rather than being direct copies of Hollywood or Hong Kong action cinema, French films are uniquely sensational based on their spectacular visuals, their narrative tendencies, and their presentation of the corporeal form. Relying on a phenomenological examination of the action film filtered through the philosophical texts of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Paul Ricoeur, Mikel Dufrenne, and Jean- Luc Marion, in this dissertation I show that French action cinema is pre-eminently concerned with the thrill that comes from the experience, and less concerned with a ii political or ideological commentary on the state of French culture or cinema. -

Joyeux Noel Autumn

keswick film Autumn club joyeux Noel Season 2009 a world of cinema Review by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat: In the opening scenes of this French film written and directed by Christian Carion, school boys in France, England, and Germany recite phrases they have been taught about the glories of their country and the scourge of their enemies. In this brief scene we see how people are brainwashed to see war as just and to believe that God is on their side. Add to this the perception that by going to war young men are protecting their families and their land, and it's easy to understand the enthusiasm that can sweep through a community at the outbreak of conflict. In 1914 Scottish brothers William (Robin Laing) and Jonathan (Steven Robertson) excitedly enlist to fight in World War I; they are looking forward to what they regard as an adventure. Palmer (Gary Lewis), their Anglican minister, goes to the front with them as a stretcher-bearer. In Berlin, Germany, a military official interrupts a performance at the opera house to announce that the country is at war. Tenor Nikolaus Sprink (Benno Furmann; songs performed by Rolando Villazon) is drafted; his lover, Anna Sorensen (Diane Kruger; songs performed by Rolando Villazon), a famous soprano, knows that their lives will never be the same again. Meanwhile, French Lieutenant Audebert (Guillaume Canet) prepares to leave for the front lines without knowing whether his wife, left in German territory, has given birth to their child. None of these men is prepared for the senseless barbarity of what is to come. -

Joyeux Noel by the First Winter of World War I, the Lines of The

Joyeux Noel By the first winter of World War I, the lines of the Western Front in Belgium and France had hardened into grim trenches while the fighting stalled preparatory to a period called the “Christmas Truce.” One vision of what happened to one group of soldiers in those trenches at that time is depicted in the new French film by Christian Carion called Joyeux Noel (“Merry Christmas”) a most sympathetic look at a soft side of men in battle (the film, in French, German, and English, opened March 24 at the E Street Cinema in Washington). Joyeux Noel, after some introductory scenes, gets us quickly to the stagnant battle field, where we witness a trio of antagonists. A French unit, led by a homesick young Lt. Andebert (Guillaume Canet), is dug in and dreading another order to advance. On their flank, a Scottish regiment, lead by Lt. Gordon (Alex Ferns), is under pressure from a senior officer, but its overall spirit is embodied by an earnest stretcher bearer, the Anglican priest Palmer (Gary Lewis), who feels responsible for young lads who’ve signed up for the fray. The German enemy trench is only yards away (in what appears to be French no-man’s- land) and led by a non-nonsense Jewish officer Horstmayer (Daniel Brühl). Among the German infantrymen is one of Europe’s great singers, the tenor Nicholas Spink (Benno Fürmann), who shares his fame with his Swedish soprano wife Anna Sorenson (Diana Kruger). It’s Christmas Eve and all the antagonists on both sides are already weary of war and thinking inevitably of home and its benign pleasures. -

Joyeux Noël Et Une Heureuse Nouvelle Année

VOLUME 36,Le #4 “AFIN D’ÊTREFORUM EN PLEINE POSSESSION DE SES MOYENS” AUTOMNE/HIVER THIS ISSUE OF LE FORUM IS DEDICATED IN LOVING MEMORY OF ALICE GÉLINAS. ALICE GRACED THE PAGES OF LE FORUM FOR MANY YEARS WITH HER MEMOIRS & POETRY. THANK YOU FOR SHARING! MAY YOU REST IN PEACE! WOLCOTT — Alice Dumas Gélinas, 97, of Wolcott, passed away on Monday, July 22, 2013 at Meridian Manor. She was the widow of Dorilla Dumas. Alice was born March 31, 1916 in St. Boniface, P.Q., Canada, daughter of the late Élizée and Désolina (LaVergne) Gélinas. She worked as a seamstress for many years and enjoyed oil painting, reading, and learning anything regarding geography. She wrote stories of the many events in her life, many of which were published and compiled her family tree going back to 1855. Alice had many pen pals and friends, but most importantly, she cherished every moment with her family. She leaves her daughter, Nicole Pelletier and her husband Paul, of Wolcott; her granddaughters, Lynn Rinaldi of Waterbury and her companion Bruno Zavarella, Michelle Cyr and her husband Bob, of Wolcott and Lorie Krol and her husband Tony, of Wolcott; her great-grandchildren, Laura and Stephen Rinaldi, Danielle and Michael Cyr, and Hailey and Alyssa Krol; her cherished nieces and Alice Dumas Gélinas nephews; and her special friends, Rob Rinaldi, Debbie Lusignan, March 31, 1916 - Lisa Michaud and Larry Capozziello. A special thank you to the staff of Meridian Manor for the ex- July 22, 2013† ceptional care given to Alice. Merry Christmas & A HappyPhoto by: Lisa DesjardinsNew -

88Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

88TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS® OSCAR® NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: The Big Short (Paramount Pictures) [Produced by Brad Pitt, Dede Gardner and Jeremy Kleiner.] - This is the sixth nomination and the third in this category for Brad Pitt, who won for 12 Years a Slave (2013). His other Best Picture nomination was for Moneyball (2011). He received Acting nominations for his supporting role in 12 Monkeys (1995) and his leading roles in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) and Moneyball. This is the fourth nomination for Dede Gardner, who won for 12 Years a Slave (2013). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Tree of Life (2011) and Selma (2014). This is the third nomination for Jeremy Kleiner, who won for 12 Years a Slave (2013) and was nominated last year for Selma. Bridge of Spies (Walt Disney and 20th Century Fox) [Produced by Steven Spielberg, Marc Platt and Kristie Macosko Krieger.] - This is the ninth nomination in this category for Steven Spielberg, who won the award in 1993 for Schindler's List. His other Best Picture nominations were for E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), The Color Purple (1985), Saving Private Ryan (1998), Munich (2005), Letters from Iwo Jima (2006), War Horse (2011) and Lincoln (2012). He has seven Directing nominations, for Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Schindler's List, Saving Private Ryan, Munich and Lincoln. He won Oscars for Schindler's List and Saving Private Ryan. He also received the Irving G. -

First World War Centenary the Imprint on National Memory, Social Groups, and Individual’S Memories

remembrance a n d s o l i d a r i t y First World War Centenary The Imprint on National Memory, Social Groups, and Individual’s Memories 1914-1918 as the Starting Point and Impulse for in 20 th century european history Discussion about Memory of other Armed Conflicts in the 20th Century issue number 2 – march 2014 www.enrs.eu EDITORIAL BOARD EDITORS: Ph. Dr. Árpád Hornják, Hungary Ph. Dr. Pavol Jakubčin, Slovakia Prof. Padraic Kenney, USA Prof. Ph. Dr. Róbert Letz, Slovakia Maria Luft, Germany Prof. Jan Rydel PhD, Poland Prof. Dr. Martin Schulze Wessel, Germany Prof. Matthias Weber, Germany EXECUTIVE EDITOR: Prof. Jan Rydel PhD, Poland EDITORIAL SECRETARY: Ph. Dr. Przemysław Łukasik, Poland REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY PUBLISHER: European Network Remembrance and Solidarity ul. Wiejska 17/3, 00-480 Warszawa, Poland tel. +48 22 891 25 00 www.enrs.eu [email protected] GRAPHIC DESIGN: Katarzyna Erbel TYPESETTING: Marcin Kiedio PROOFREADING: Marek Darewski Cover DESIGN: © European Network Remembrance and Solidarity 2014 All rights reserved ISSN: 2084-3518 Circulation: 1000 copies The volume was funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media upon a decision of the German Bundestag. In cooperation with the Institute for the Culture and History of the Germans in North Eastern Europe. Photo on the front cover: The Royal Artillery Memorial for Those Who Died in World War I at Hyde Park Corner © Walter Bibikow / Corbis / FotoChannels Photo on the back cover: © Karel Cudlín REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY ISSUE NUMBER 2 MARCH 2014 CONTENTS Editor’s Preface 6 Editors ARTICLES Interpretation AND MEDIA Was the War Inevitable? 15 Andrzej Chwalba Turning Points in the History of War: Criteria for the Meaning 25 of Violence in the Great War of 1914–1918 Christian Wevelsiep Memory in the Digital Age: First World War and Its 47 Representation on the Web Aleksandra Pawliczek The Christmas Truce of 1914 – Remembered in 2005. -

The Christmas Truce of 1914 in the Film Joyeux Noël (2005)

THE CHRISTMAS TRUCE OF 1914 IN THE FILM JOYEUX NOËL (2005) IVAN KOVAČEVIĆ The 2005 film Joyeux Noël describes events on the Western Film Joyeux Noël iz leta 2005 opisuje dogodke na zahodni Front on Christmas Day in 1914. After several months of fronti na božični dan leta 1914. Po nekaj mesecih težkih trench warfare under difficult weather conditions, singing bitk v rovih in nadvse neprijetih vremenskih razmerah je s carols on Christmas Eve began a spontaneous truce known petjem na božični večer začelo spontano premirje, znano kot as the Christmas Truce, which included Christmas day itself. božični premor, ki je vključeval tudi božični dan. The analysis of the film traces the French-German conflicts, Analiza filma zasleduje francosko-nemške konflikte, možnosti the possibility of joint action by Christian churches, and skupnega delovanja krščanskih cerkva in elementov interakcije. elements of interaction. Ključne besede: Prva svetovna vojna, Zahodna fronta, Keywords: First World War, Western Front, Christmas Božično premirje, film, Joyeux Noël, evropska integracija, Truce, film, Joyeux Noël, European integration, French- francosko-nemški odnosi, ekumenizem, evropska identiteta German relations, ecumenism, European identity JOYEUX NOËL: PRODUCTION, CONTENT, RECEPTION, PRECURSORS The film Joyeux Noël (2005) is a story of the Christmas Truce and fraternization of warring parties on the Western Front in December 1914. The film was co-produced by companies from five countries. The French producer Nord-Ouest is listed as the main producer, and the coproduction partners are Senator Film Produktion from Germany, The Bureau from the UK, Artémis Productions from Belgium, Media Pro Pictures from Romania, and the French TV channel TF1 Films Production. -

Joyeux Noël and Remembering the Christmas Truce of 1914

Shane A. Emplaincourt Joyeux Noël and Remembering the Christmas Truce of 1914 “What would happen, I wonder, if the armies suddenly and simultaneously went on strike and said some other method must be found of settling the dispute?”—Winston Churchill to his wife, Clementine, November 23, 1914.1 Preface: July Crisis of 1914 ne hundred years ago this July, a crisis occurs that would forever change our world: The July Crisis of 1914, a rapid series of events that, like falling dominos, lead to The Great War. The first domino to fall occurs O28 June 1914 with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo by Bosnians affiliated with the “Black Hand;” then, 5-6 July, Germany issues a “blank check” to Austria; 28 July, Austria declares war on Serbia; 30 July, Russia orders general mobilization of its army reserves; 31 July, Germany delivers a twelve-hour ultimatum to Russia; 1-2 August, Germany declares war on Russia but enters Luxemburg and threatens Belgium; 3 August, France declares war on Germany; and 4 August, Germany invades neutral Belgium, and Britain declares war on Germany. In summary, four declarations of war take place in seven days’ time, and The Great War begins. 1 Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History, (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co., 1994) 25. Introduction Exactly five years after the “the fall of the first domino,” The Treaty of Versailles is signed 28 June 1919, ending the state wars between Germany and the allies and, shortly afterwards, the war movie genre is born with William Nigh’s 1919 production of James W. -

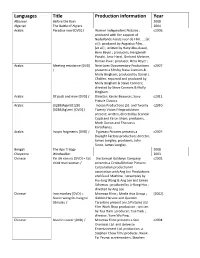

Foreign Language Films

Languages Title Production Information Year Albanian Before the Rain 2008 Algerian The Battle of Algiers 2004 Arabic Paradise now [DVD] / Warner Independent Pictures ; c2006. produced with the support of Nederlands Fonds voor de Film, ... [et al.] ; produced by Augustus Film, ... [et al.] ; written by Hany Abu-Assad, Bero Beyer ; producers, Hengameh Panahi, Amir Harel, Gerhard Meixner, Roman Paul ; producer, Bero Beyer ; Arabic Meeting resistance [DVD] Nine Lives Documentary Productions c2007. / presents a film by Steve Connors & Molly Bingham; produced by Daniel J. Chalfen; reported and produced by Molly Bingham & Steve Connors; directed by Steve Connors & Molly Bingham. Arabic Of gods and men [DVD] / Director: Xavier Beauvois, Sony c2011. Picture Classics. Arabic {02BB}Ajam{012B} Inosan Productions Ltd. and Twenty c2010. {02BB}Ag'ami [DVD] / Twenty Vision Filmproduktion present; written, directed by Scandar Copti and Yaron Shani; producers, Mosh Danon and Thanassis Karathanos. Arabic Iraq in fragments [DVD] / Typecast Pictures presents a c2007. Daylight Factory production; director, James Longley; producers, John Sinno, James Longley. Bengali The Apu Trilogy 2008 Cheyenne Windwalker 2003 Chinese Yin shi nan nü [DVD] = Eat the Samuel Goldwyn Company c2002. drink man woman / presents a Central Motion Pictures Corporation production in association with Ang Lee Productions and Good Machine ; screenplay by Hui-Ling Wang & Ang Lee and James Schamus ; produced by Li-Kong Hsu ; directed by Ang Lee. Chinese Iron monkey [DVD] = Miramax Films ; Media Asia Group ; [2002]. Siunin wong fei-hung tsi Golden Harvest and Quentin titmalau / Tarantino present an LS Pictures Ltd. Film Work Shop production ; written by Tsui Hark ; producer, Tsui Hark ; director, Yuen Wo Ping. -

J&Rsquo;Aimerais Comprendre D&Rsquo;Avantage Le

J’aimerais comprendre d’avantage le contexte et la « mémoire » sans doute très subjective défendue dans le film Joyeux Noel de Christian Carion….pourtant trouver de bonnes sources sur ce film encore récent me parait difficile !Pouvez vous m’aider? Réponse apportée le 03/21/2014 par PARIS Bpi – Actualité, Art moderne, Art contemporain, Presse Avez-vous lu en détail les deux articles de Wikipédia concernant le film et la trêve de Noël dans les tranchées ? Trêve de Noël http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tr%C3%AAve_de_No%C3%ABl> Les références sont détaillées et comportent des liens exploitables ainsi qu’une bibliographie : *Rémy Cazals, Marc Ferro, Malcolm Brown et Olaf Mueller, Frères de tranchées, Perrin – Tempus, octobre 2006, 324 p. (ISBN 2-262-02159-7) *Christian Carion, Joyeux Noël, Perrin, octobre 2005, 177 p. (ISBN 2-262-02400-6) *Michael Morpurgo, La trêve de Noël, Gallimard Jeunesse, coll. « Albums Junior », 13 octobre 2005, 36 p. (ISBN 2070571890 et 978-2070571895) *Éric Simard (ill. Nathalie Girard), Les soldats qui ne voulaient plus se faire la guerre : Noël 1914, coll. « Cadet 8-12 ans », 39 p. (ISBN 2350000451) *Yves Buffetaut, Batailles de Flandres et d’Artois, 1914-1918, Tallandier, coll. « Guides Historia », 1er juillet 1992, 95 p. (ISBN 978-2235020909) Le film Article Joyeux Noël http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joyeux_No%C3%ABl_(film)> Base IMDB (Internet movie database) Fiche du film http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0424205/combined> Liste des articles sur le film (tous les liens ne sont pas intéressants et mènent souvent au lien général de la revue) http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0424205/externalreviews> par exemple, l’article du New York Times Voici les références de la presse française issues de Bpi-doc (base de presse constituée par la Bpi) qui propose en ligne les références d’une sélection d’articles issus de la presse française sur les questions d’actualité sociale et culturelle en France et dans le monde. -

Christmas Truce Mine

Joyeux Noel! Frohe Name ___________________-____ Weihnachten! Happy Christmas! Mark up the text: Question, Connect, Predict (Infer), Clarify (Paraphrase), and Evaluate (at least one of each type of annotation). Circle unfamiliar words, draw arrows to make connections within the text, use exclamation points & question marks in the margin, and label examples (EX). The Christmas Truce of 1914 One hundred and one years ago on Christmas 1914, an event took place that may be considered as one of the most extraordinary moments in the history of modern warfare. In northern France, along 440-mile network of trenches separating the German army from its French and British enemies, soldiers on both sides stopped fighting. War Erupts A few months earlier in August 1914 a titanic clash of armies began. For years Germany had been planning to invade France, and after a quick victory, send troops to defeat Russia before the “Russian Bear” could become a serious rival to Germany. The time to carry out these plans came unexpectedly when Serbian nationalists assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne. Germany, Russia, France, and then England were drawn into the conflict. This war, which would come to be known as the Great War, was supposed to be over before Christmas. Instead of a swift victory for one side, the war became a virtual stalemate as both sides literally “dug in” by creating miles of defensive trenches—long narrow pits from which soldiers could fire machine guns at an attacking enemy. Neither side could gain an advantage against an entrenched enemy. The space that separated enemy lines (sometimes as little as a hundred yards distance) was filled with barbed wire and was dubbed “no man’s land.” Occasionally one side or the other would attempt an infantry charge.