Georgians on the Titanic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Titanic Research Project What Is It? You Will Choose a Person Involved with the Titanic from the List Provided by Your Teacher

Titanic Research Project What is it? You will choose a person involved with the Titanic from the list provided by your teacher. Steps for your research 1. You will gather information about your person by reading articles, online resources, and books. 2. You will take notes on important facts about your person and keep them in your folder. 3. You will organize your facts and sort them into like categories that will become your sections/subheadings of your expository essay. 4. You will create a thinking map and put your information into a thinking map. 5. You will write the draft of your expository essay. 6. You will revise and add transitional words, fix the any of the words in your essay. 7. You will edit your essay and check for spelling, punctuation, and capitalization. 8. You will publish your essay. If time permits you will be able to type your report. When is it due? January 6, 2017 When is the Titanic Live Museum? The week of January 9th exact times and date TBD What materials do you need? Writing folder Internet access at home or school Access to books The Titanic articles given to you by your teacher Supplies for your presentation at the Titanic Live Museum—this will vary depending on what you decide to do What is a live museum? A living museum is a museum which recreates a historical event by using props, costumes, decorations, etc. in which the visitors will feel as though they are literally visiting that particular event or person(s) in history. -

Geographical List of Public Sculpture-1

GEOGRAPHICAL LIST OF SELECTED PERMANENTLY DISPLAYED MAJOR WORKS BY DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH ♦ The following works have been included: Publicly accessible sculpture in parks, public gardens, squares, cemeteries Sculpture that is part of a building’s architecture, or is featured on the exterior of a building, or on the accessible grounds of a building State City Specific Location Title of Work Date CALIFORNIA San Francisco Golden Gate Park, Intersection of John F. THOMAS STARR KING, bronze statue 1888-92 Kennedy and Music Concourse Drives DC Washington Gallaudet College, Kendall Green THOMAS GALLAUDET MEMORIAL; bronze 1885-89 group DC Washington President’s Park, (“The Ellipse”), Executive *FRANCIS DAVIS MILLET AND MAJOR 1912-13 Avenue and Ellipse Drive, at northwest ARCHIBALD BUTT MEMORIAL, marble junction fountain reliefs DC Washington Dupont Circle *ADMIRAL SAMUEL FRANCIS DUPONT 1917-21 MEMORIAL (SEA, WIND and SKY), marble fountain reliefs DC Washington Lincoln Memorial, Lincoln Memorial Circle *ABRAHAM LINCOLN, marble statue 1911-22 NW DC Washington President’s Park South *FIRST DIVISION MEMORIAL (VICTORY), 1921-24 bronze statue GEORGIA Atlanta Norfolk Southern Corporation Plaza, 1200 *SAMUEL SPENCER, bronze statue 1909-10 Peachtree Street NE GEORGIA Savannah Chippewa Square GOVERNOR JAMES EDWARD 1907-10 OGLETHORPE, bronze statue ILLINOIS Chicago Garfield Park Conservatory INDIAN CORN (WOMAN AND BULL), bronze 1893? group !1 State City Specific Location Title of Work Date ILLINOIS Chicago Washington Park, 51st Street and Dr. GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, bronze 1903-04 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, equestrian replica ILLINOIS Chicago Jackson Park THE REPUBLIC, gilded bronze statue 1915-18 ILLINOIS Chicago East Erie Street Victory (First Division Memorial); bronze 1921-24 reproduction ILLINOIS Danville In front of Federal Courthouse on Vermilion DANVILLE, ILLINOIS FOUNTAIN, by Paul 1913-15 Street Manship designed by D.C. -

History of the Jews

II ADVERTISEMENTS Should be in Every Jewish Home AN EPOCH-MAKING WORK COVERING A PERIOD OF ABOUT FOUR THOUSAND YEARS PROF. HE1NRICH GRAETZ'S HISTORY OF THE JEWS THE MOST AUTHORITATIVE AND COMPREHENSIVE HISTORY OF THE JEWS IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE HANDSOMELY AND DURABLY BOUND IN SIX VOLUMES Contains more than 4000 pages, a Copious Index of more than 8000 Subjects, and a Number of Good Sized Colored Maps. SOME ENTHUSIASTIC APPRECIATIONS DIFFICULT TASK PERFORMED WITH CONSUMMATE SKILL "Graetz's 'Geschichte der Juden1 has superseded all former works of its kind, and has been translated into English, Russian and Hebrew, and partly into Yiddish and French. That some of these translations have been edited three or four times—a very rare occurrence in Jewish literature—are in themselves proofs of the worth of the work. The material for Jewish history being so varied, the sources so scattered in the literatures of all nations, made the presentation of this history a very difficult undertaking, and it cannot be denied that Graetz performed his task with consummate skill."—The Jewish Encyclopedia. GREATEST AUTHORITY ON SUBJECT "Professor Graetz is the historiographer par excellence of the Jews. His work, at present the authority upon the subject of Jewish History, bids fair to hold its pre-eminent position for some time, perhaps decades."—Preface to Index Volume. MOST DESIRABLE TEXT-BOOK "If one desires to study the history of the Jewish people under the direction of a scholar and pleasant writer who is in sympathy with his subject, because he is himself a Jew, he should resort to the volumes of Graetz."—"Review ofRevitvit (New York). -

How to Survive the Titanic Or the Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay Free

FREE HOW TO SURVIVE THE TITANIC OR THE SINKING OF J. BRUCE ISMAY PDF Frances Wilson | 352 pages | 14 Mar 2012 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408828151 | English | London, United Kingdom The Life of Bruce Ismay After Titanic’s Sinking – Part Two How to Survive the Titanic. Or The Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay Frances Wilson, Bloomsbury. Frances Wilson invokes Herman Melville to compare Ismay to Captain Ahab and even to Noah in this often ludicrous bookbut predominantly plumps for Joseph Conrad in her meditation on the life - and the elemental living - of this single individual, in whom is seemingly forever embarked the fate of fifteen hundred. The first syllable asserts enduring existence, the second an implication of twin alternatives. Ismay lived, and his reputation died. Had he not entered collapsible C it is scarcely imaginable that anyone would have branded him a coward. Instead mere mortality would have conferred its very opposite, in the palpable vein of an Isidor Straus or any other drowned potentate of the merchant classes. But such is a preserved-in-amber afterlife. With Ismay, though he now be dead, we can still poke the wounds. And so Wilson, as sanguinary soothsayer, enters into her very own launch — because this is a commercial voyage, complete with the richly absurd sales claim that Ismay fell in love with a married passenger on the maiden voyage. He did no such thing. It is as well that this work is largely a meditation — albeit with some interesting photographs and detail provided by the Cheape family — as the author seems only rudimentarily acquainted with the Titanic story. -

RMS Titanic - Wikipedia

RMS Titanic - Wikipedia http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Titanic RMS Titanic Da Wikipedia, l'enciclopedia libera. « Nemmeno Dio potrebbe fare affondare questa RMS Titanic nave. » (Il marinaio A.Bardetta del Titanic alla signora Caldwell, il 10 aprile 1912.) Il RMS Titanic era una nave passeggeri britannica della Olympic Class , divenuta famosa per la collisione con un iceberg nella notte tra il 14 e il 15 aprile 1912, e il conseguente drammatico affondamento avvenuto nelle prime ore del giorno successivo. Secondo di un trio di transatlantici, il Titanic , con le sue Descrizione generale due navi gemelle Olympic e Britannic , era stato progettato per offrire un collegamento settimanale con l'America, e Tipo Transatlantico garantire il dominio delle rotte oceaniche alla White Star Classe Olympic Line. Costruttori Harland and Wolff Cantiere Belfast, Irlanda del Nord. Costruito presso i cantieri Harland and Wolff di Belfast, il Titanic rappresentava la massima espressione della Impostazione 31 marzo 1909 tecnologia navale, ed era il più grande, veloce e lussuoso Completamento 31 marzo 1912 Entrata in transatlantico del mondo. Durante il suo viaggio inaugurale 10 aprile 1912 (da Southampton a New York, via Cherbourg e servizio Queenstown), entrò in collisione con un iceberg alle 23:40 Proprietario White Star Line, (ora della nave) di domenica 14 aprile 1912. L’impatto Amministratore Delegato: (Joseph Bruce Ismay) provocò l'apertura di alcune falle lungo la fiancata destra Destino finale Naufragato il 15 aprile 1912. del transatlantico, che affondò due ore e 40 minuti più tardi (alle 2:20 del 15 aprile) spezzandosi in due tronconi. Caratteristiche generali Dislocamento 52.310 t Nella sciagura, una delle più grandi tragedie nella storia Stazza lorda 46.328 t della navigazione civile, persero la vita 1517 dei 2227 Lunghezza 269 m passeggeri imbarcati. -

Teacher's Guide

MIDDLE SCHOOL TEACHER’S GUIDE CLASSROOM LESSON PLANS AND FIELD TRIP ACTIVITIES Winner of a 2007 NAI Interpretive Media Award for Curriculum 1 Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 3 GETTING READY ....................................................... 4 Preparing to Visit the Exhibition Winner of a 2007 NAI What Students Want to Know Interpretive Media Award Chaperone Responsibilities for Curriculum The History of Titanic National Curriculum Standards CLASSROOM LESSON PLANS AND ......................... 8 FIELD TRIP ACTIVITIES Middle School ADDITIONAL STUDENT ACTIVITIES ................... 25 Premier Exhibitions, Inc. 3340 Peachtree Road, NE Field Trip Scavenger Hunt Suite 2250 Word Search Atlanta, GA 30326 Crossword Puzzles RMS Titanic www.rmstitanic.net Answer Key Content: Cassie Jones & Cheryl Muré, APPENDIX .................................................................. 31 with Joanna Odom & Meredith Vreeland Interdisciplinary Activities Project Ideas Design: Premier Exhibitions, Inc. Facts & Figures © 2009 Premier Exhibitions, Inc. Primary Sources: Eyewitness Reports All rights reserved. Except for educational fair Newspaper Headlines use, no portion of this guide may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any Ship Diagram form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, Epilogue: Carpathia photocopy, recording, or any other without ex- plicit prior permission from Premier Exhibitions, Inc. Multiple copies may only be made by or for the teacher for class use. 2 Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition INTRODUCTION We invite you and your school group to see ...a great catalyst for Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition and take a trip back in time. The galleries in this lessons in Science, fascinating Exhibition put you inside the History, Geography, Titanic experience like never before. They feature real artifacts recovered from the English, Math, and ocean floor along with room re-creations Technology. -

RMS Titanic - New World Encyclopedia

4/11/2021 RMS Titanic - New World Encyclopedia archive.today Saved from https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/RMS_Titanic search 11 Apr 2021 04:25:40 UTC webpage capture no other snapshots from this url All snapshots from host www.newworldencyclopedia.org Webpage Screenshot share download .zip report bug or abuse donate Pay Less, Download More! Save 15% off in any stock photos & images. Get started! ADS VIA CARBON É RMS Titanic Previous (R. M. Hare) Next (RNA) The RMS Titanic, a British Olympic class ocean liner, became famous as the largest ocean liner built in her day and infamous for sinking on her maiden voyage, in 1912. This event ranks as one of the worst peacetime maritime disasters in history. On the night of April 14, at 11:40 p.m., the ship struck an iceberg and sank in just under three hours with the loss of approximately 1500 lives. There are many descriptions of the disaster by the surviving passengers and crew and the sinking has been the subject of numerous investigations. The sinking of the RMS Titanic was a factor that influenced later maritime practices, ship design, and the seafaring culture. Contents [hide] BuildTihneg RMS Titanic leaving Belfast for sea trials, 2 April 1912 1 Building and design and History 2 Fixtures and fittings design 3 Passengers and crew Class and Olympic-class ocean liner In type: 3.1 Crew Builder: Harland and Wolff shipyard, 3.2 Passengers Belfast 4 Disaster Laid down: 31 March 1909 5 Contributing factors Launched: 31 May 1911 5.1 Speed Christened: Not christened, as per White 5.2 Lifeboats Star Line practice 5.3 Manuevering Status: Sunk 5.4 struck iceberg at 23:40 (ship's time) on Faults in construction or 14 April 1912 substandard materials sank the next day at 2:20. -

The Birmingham Age Herald Number 332 Volume Xnxxi Birmingham, Alabama, Tuesday’ April 23, 19.12 11 Pages

THE BIRMINGHAM AGE HERALD_ NUMBER 332 VOLUME XNXXI BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA, TUESDAY’ APRIL 23, 19.12 11 PAGES -- ... — --—-------Pi- -- ^ -■-■ ....... ■ ■ ■ n -—-- --—-* THE TITANIC SANK VICE PRESIDENT FRANKLIN ADMITS THERE WERE NOT ENOUGH UNDERWGGD TALKS BELOW WITH SUCCOR ONLY LIFE BOATS ON THE TITANIC—THEY ARE SHOWN BFPARTY’SWORKIN ' FIVE MILES AWAY, DECLARES OFFICER PLANS FOR FUTURE Fourth Officer Tells of Unidentified Steamer That Ignored Frantic Reached Birmingham Last Night to Be Present at Calls Ad- for Help—Franklin His Son’s Wedding mits Lack of Enough Boats Tomorrow Night 22.—With succor five miles Washington, April only away, THINKS the Titanic slid into its watery grave, carrying with it more DEMOCRATS ARE SURE TO WIN than 1600 of its passengers and crew, while an unidentified IN COMING ELECTION steamer that might have saved all, failed or refused to see the frantic signals flashed to it for aid. This phase of the tragic disaster was brought out today before the Senate investigation Expresses Appreciation of Alabama's committee, when ,T. B. Boxhall, fourth officer of the Titanic, Recent Action in Sending Delega- The lack of a sufficient amount of lifeboats on board Is now believed to have tion for Him to Baltimore—In told of his unsuccessful attempts to attract the stranger’s at- been responsible for the frightful loss of life when the giant Titanic plunged to / Excellent Health Except tention. the bottom. The type of lifeboat used on the vessel is also severely criticized. I for a Slight Cold This to could not have been more ship, according Boxhall, They were collapsible and Inadequately equipped for an accident of the kind I than five miles and was toward Titanic. -

“R.M.S. Titanic” Hanson W

“R.M.S. Titanic” Hanson W. Baldwin I The White Star liner Titanic, largest ship the world had ever known, sailed from Southampton on her maiden voyage to New York on April 10, 1912. The paint on her strakes was fair and bright; she was fresh from Harland and Wolff’s Belfast yards, strong in the strength of her forty-six thousand tons of steel, bent, hammered, shaped, and riveted through the three years of her slow birth. There was little fuss and fanfare at her sailing; her sister ship, the Olympic—slightly smaller than the Titanic— had been in service for some months and to her had gone the thunder of the cheers. But the Titanic needed no whistling steamers or shouting crowds to call attention to her superlative qualities. Her bulk dwarfed the ships near her as longshoremen singled up her mooring lines and cast off the turns of heavy rope from the dock bollards. She was not only the largest ship afloat, but was believed to be the safest. Carlisle, her builder, had given her double bottoms and had divided her hull into sixteen watertight compartments, which made her, men thought, unsinkable. She had been built to be and had been described as a gigantic lifeboat. Her designers’ dreams of a triple-screw giant, a luxurious, floating hotel, which could speed to New York at twenty-three knots, had been carefully translated from blueprints and mold loft lines at the Belfast yards into a living reality. The Titanic’s sailing from Southampton, though quiet, was not wholly uneventful. -

Titanic and the People on Board: a Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking Andrea Bijan Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History Spring 2014 Titanic and the People on Board: A Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking Andrea Bijan Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bijan, Andrea, "Titanic and the People on Board: A Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking" (2014). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 27. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/27 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Titanic and the People on Board: A Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking By Andrea Bijan Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor David Doellinger Western Oregon University June 4, 2014 Readers Professor Kimberly Jensen Professor David Doellinger Copyright © Andrea Bijan 2014 2 The Titanic was originally called the ship that was “unsinkable” and was considered the most luxurious liner of its time. Unfortunately on the night of April 14, 1912 the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank early the next morning, losing many lives. The loss of life made Titanic one of the worst maritime accident in history. Originally having over 2,200 passengers and crew on board only about 700 survived; most of the survivors being from the upper class. -

2012-Winter.Pdf

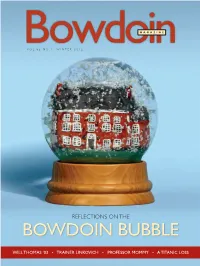

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE VOL. 83 VOL.83 N O.1 WINTER 2012 N O. 1 WINTER 2012 O. 1 WINTER 2012 Bowdoi n REFLECTIONS ON THE BOWDOIN BUBBLE Will Thomas ’03 • Trainer linkovich • Professor mommy • a TiTanic loss Bowdoin Cover.indd 1 3/2/12 12:18 PM MAGAZINE Bowdoin WINTER 2012 CONTENTS 20 Reflections on the Bowdoin Bubble 42 Mike Linkovich, Trainer for all Seasons Photo essay by Bob Handelman. “The Bowdoin Bubble BY DAVID TREADWEll ’64 Provides Room for Thought” by Craig Hardt ’12. If you graduated from Bowdoin in the last 57 years – especially if you played a sport, any sport – you’ll know this man’s name: Mike Linkovich. 36 Make Room for Mommy By Lisa WeseL • PhotograPhs By James marshaLL 46 Running Man Professors Connelly and Ghodsee talk about their By ian aLdrich • PhotograPhs By Brian Wedge ’97 book outlining ways to combine motherhood with academia, and do both jobs well. Will Thomas ’03 paired an entrepreneurial spirit with a hardcore athletic drive to found a niche company in Bowdoin’s backyard. 30 The Highest Example Life Can Furnish By micheLe aLBion One hundred years ago, the Titanic hit an iceberg and sunk on its maiden voyage. Richard Frazar White, of the Bowdoin Class of 1912, was sailing back from a journey abroad with his father and perished, along with his father, in the disaster. Michele Albion tells of the tragedy and DEPARTMENTS its impact on White’s classmates and his young niece, Bookshelf 2 Class News 57 Matilda White, who would go on to become the first Bowdoinsider 6 Weddings 79 woman to be named a full professor at Bowdoin. -

RMRT Production History

Show Sponsor S ho w S p o ns or 2 www.RockyMountainRep.com • 970.627.3421 Sh ow Sp on sor We're happy you are a part of Our World. Water Lovers! Homes from $250,000. Land, Lake & Riverfront, Income proper ties, Scenery, Wild life, Hikes, Vid eos at www.MountainLake.com Email [email protected] and tell us what you would like to own in Grand Lake. Visit us at the east end of the Boardwalk. ( 970-627-3103 r nso ow Spo Sh www.RockyMountainRep.com • 970.627.3421 3 Welcome For each of the years that I have been President of RMRT I have worked hours to prepare a Presi- dent’s message that fills half a page in each years playbill. My guess is that only a quarter of you read that message in its entirety. This year I have decided to keep it very simple and therefore I have four things to tell you. 1. We, the Board of Trustees and our Staff, work very hard 12 months of the year to bring you the best in musical theatre. 2. We truly appreciate your support (in whatever form that may be) for without you this not-for- profit organization could not exist. 3. We are very glad that you joined us today, to sit amongst your friends, as part of our RMRT family. 4. We hope you Enjoy the Show! RMRT President 49 and counting......... Judy K. Jensen - President RMRT Our Mission Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre’s mission is to stimulate, promote and develop interest in the performing arts in Grand County, Colorado, and the surrounding region through live theatrical productions and youth theatre educational workshops.