The Physician's Tale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delivering a Safe and Welcoming Night Time Economy Our Plan 2017-2022 DRAFT DRAFT Contents

Delivering a Safe and Welcoming Night Time Economy Our Plan 2017-2022 DRAFT DRAFT Contents Foreword Page 2 Introduction Page 3 What is the night time economy Page 3 Cardiff demographics Page 4 Footprint Page 4 Public health and the night time economy Page 6 Delivering together Page 7 Aims of the strategy Page 7 • Priorities Page 7 Movement in and around the city Page 8 • What’s going well? Page 9 • What we want to develop Page 9 • Action Plan One Page 10 Preventing crime and disorder in the night time economy Page 11 • What’s going well Page 11 • What we want to develop Page 12 • Action Plan Two Page 12 A safe and welcoming night time economy for all Page 15 • What’s going well Page 16 DRAFT• What we want to develop Page 17 • Action Plan Three Page 18 Strategic and Legislative Context Page 21 • Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 Page 21 • Cardiff’s Shared Outcomes Page 22 1 Foreword Cardiff has a thriving daytime economy and Cardiff already has a proven record of is renowned for successfully hosting large ensuring safety and wellbeing of those who sporting and cultural events. Based on this use and work in the night time economy. success and as one of the fastest growing This relies on close partnership working cities in the UK, the popularity of Cardiff’s between a range of partners, many of whom night time economy can only be expected are facing cutbacks in funding as a result of to increase. We are already seeing smaller austerity. -

View Playlist

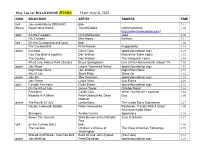

Play List for ROAD HOME #1486 Date: July 4, 2021 KIND SELECTION ARTIST SOURCE TIME talk July celebrations OPENING bob 3:11 theme Road Home theme The McDades (commissioned: 1:00 http://www.themcdades.com) poet A Little Freedom Clint McElwaine Gold 2:03 Oh, Canada Mae Moore Folklore 3:11 talk On the Cuckoo bird and song bob 1:04 The Cuckoo Bird Peter Rowan Reggaebilly! 3:14 poem Cuckoos Dana Gioia (poetryfoundation.org) 2:28 Coo Coo Bird (a capella) Doc Watson Round the Table Again 1:52 The Cuckoo Doc Watson The Vanguard Years 2:45 4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy) Bruce Springsteen Live at the Hammersmith Odeon ’75 7:06 poem July Moon Louise Townsend Nichol (poetryfoundation.org) 1:41 Night Ride Home Joni Mitchell Night Ride Home 2:57 4th Of July Steve Poltz Shine On 3:52 poem July 4th May Swenson (poetryfoundation.org) 1:32 July Flame Laura Veirs July Flame 2:09 poet Canada Anemone Fleda Brown (poetryfoundation.org) 2:23 On the 4th of July James Taylor October Road 3:16 Fireworks Caitlin Cary While You Weren`t Looking 3:48 Musette In A Minor Peter Ostroushko, Dean Duo 1:00 Magraw prose The Fourth Of July Lynda Barry The Lynda Barry Experience 2:57 Dayton Cakewalk Delight Peter Ostroushko Postcards: Travels With A Great 1:00 American Radio Show Strangers Amelia Curran Spectators 3:25 Above The Ground Mark Berube & the Patriotic June In Siberia 3:17 Few talk on the Cuckoo bird 2 bob 2:56 The Cuckoo Children`s Chorus of The Great American Folksongs 2:59 Washington Wicked And Weird - Coo Coo Bird Buck 65 and John Zytaruk (YouTube) 3:51 poem -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

The Rhesus Factor and Disease Prevention

THE RHESUS FACTOR AND DISEASE PREVENTION The transcript of a Witness Seminar held by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, London, on 3 June 2003 Edited by D T Zallen, D A Christie and E M Tansey Volume 22 2004 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 2004 First published by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2004 The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at University College London is funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 0 85484 099 1 Histmed logo images courtesy Wellcome Library, London. Design and production: Julie Wood at Shift Key Design 020 7241 3704 All volumes are freely available online at: www.history.qmul.ac.uk/research/modbiomed/wellcome_witnesses/ Please cite as : Zallen D T, Christie D A, Tansey E M. (eds) (2004) The Rhesus Factor and Disease Prevention. Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, vol. 22. London: Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL. CONTENTS Illustrations and credits v Witness Seminars: Meetings and publications;Acknowledgements vii E M Tansey and D A Christie Introduction Doris T Zallen xix Transcript Edited by D T Zallen, D A Christie and E M Tansey 1 References 61 Biographical notes 75 Glossary 85 Index 89 Key to cover photographs ILLUSTRATIONS AND CREDITS Figure 1 John Walker-Smith performs an exchange transfusion on a newborn with haemolytic disease. Photograph provided by Professor John Walker-Smith. Reproduced with permission of Memoir Club. 13 Figure 2 Radiograph taken on day after amniocentesis for bilirubin assessment and followed by contrast (1975). -

Clinical Genetics in Britain: Origins and Development

CLINICAL GENETICS IN BRITAIN: ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT The transcript of a Witness Seminar held by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, London, on 23 September 2008 Edited by P S Harper, L A Reynolds and E M Tansey Volume 39 2010 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 2010 First published by the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2010 The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL is funded by the Wellcome Trust, which is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 085484 127 1 All volumes are freely available online following the links to Publications/Wellcome Witnesses at www.ucl.ac.uk/histmed CONTENTS Illustrations and credits v Abbreviations vii Witness Seminars: Meetings and publications; Acknowledgements E M Tansey and L A Reynolds ix Introduction Sir John Bell xix Transcript Edited by P S Harper, L A Reynolds and E M Tansey 1 Appendix 1 Initiatives supporting clinical genetics, 1983–99 by Professor Rodney Harris 83 Appendix 2 The Association of Genetic Nurses and Counsellors (AGNC) by Professor Heather Skirton 87 References 89 Biographical notes 113 Glossary 133 Index 137 ILLUSTRATIONS AND CREDITS Figure 1 Professor Lionel Penrose, c. 1960. Provided by and reproduced with permission of Professor Shirley Hodgson. 8 Figure 2 Dr Mary Lucas, clinical geneticist at the Galton Laboratory, explains a poster to the University of London’s Chancellor, Princess Anne, October 1981. Provided by and reproduced with permission of Professor Joy Delhanty. 9 Figure 3 (a) The karyotype of a phenotypically normal woman and (b) family pedigree, showing three generations with inherited translocation. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Reflections of Children in Holocaust Art (Essay) Josh Freedman Pnina Rosenberg 98 Shoshana (Poem) 47 the Blue Parakeet (Poem) Reva Sharon Julie N

p r an interdisciplinary journal for holocaust educators • a rothman foundation publication ism • an interdisciplinary journal for holocaust educators AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATORS E DITORS: DR. KAREN SHAWN, Yeshiva University, NY, NY DR. JEFFREY GLANZ, Yeshiva University, NY, NY EDITORIAL BOARD: DARRYLE CLOTT, Viterbo University, La Crosse, WI yeshiva university • azrieli graduate school of jewish education and administration DR. KEREN GOLDFRAD, Bar-Ilan University, Israel BRANA GUREWITSCH, Museum of Jewish Heritage– A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, NY, NY DR. DENNIS KLEIN, Kean University, NJ DR. MARCIA SACHS LiTTELL, School of Graduate Studies, The Richard Stockton College of New Jersey DR. ROBERT ROZETT, Yad Vashem DR. DAVID ScHNALL, Yeshiva University, NY, NY DR. WiLLIAM SHULMAN, Director, Association of Holocaust Organizations DR. SAMUEL TOTTEN, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville DR. WiLLIAM YOUNGLOVE, California State University Long Beach ART EDITOR: DR. PNINA ROSENBERG, Ghetto Fighters’ Museum, Western Galilee POETRY EDITOR: DR. CHARLES AdÉS FiSHMAN, Emeritus Distinguished Professor, State University of New York ADVISORY BOARD: STEPHEN FEINBERG, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum DR. HANITA KASS, Educational Consultant DR. YAACOV LOZOWICK, Historian YITZCHAK MAIS, Historian, Museum Consultant GERRY MELNICK, Kean University, NJ RABBI DR. BERNHARD ROSENBERG, Congregation Beth-El, Edison; NJ State Holocaust Commission member MARK SARNA, Second Generation, Real Estate Developer, Attorney DR. DAVID SiLBERKLANG, Yad Vashem SIMCHA STEIN, Ghetto Fighters’ Museum, Western Galilee TERRI WARMBRAND, Kean University, NJ fall 2009 • volume 1, issue 1 DR. BERNARD WEINSTEIN, Kean University, NJ DR. EFRAIM ZuROFF, Simon Wiesenthal Center, Jerusalem AZRIELI GRADUATE SCHOOL DEPARTMENT EDITORS: DR. SHANI BECHHOFER DR. CHAIM FEUERMAN DR. ScOTT GOLDBERG DR. -

2019 Half Year Results Improving Lives Through Inclusive Capitalism

2019 Half year results Improving lives through Inclusive Capitalism December 2019 LEGAL & GENERAL GROUP PLC LEGAL & GENERAL GROUP PLC | HALF YEAR RESULTS | AUGUST 2019 Financial highlights Operating profit from divisions Earnings per share Return on equity £1,186m 14.74p 20.2% (H1 2018: £1,059m) (H1 2018: 13.00p) (H1 2018: 20.3%) +12% +13% Book value SII operational surplus generation Interim dividend £8.7bn, 146p £0.8bn 4.93p (H1 2018: £7.7bn, 129p) (H1 2018: £0.7bn) (H1 2018: 4.60p) +13% +17% +7% 2 LEGAL & GENERAL GROUP PLC LEGAL & GENERAL GROUP PLC | HALF YEAR RESULTS | AUGUST 2019 An established track record of consistent growth Operating profit from divisions1 (£m) Earnings per share (p) 11% CAGR 2011 - 2018 2,231 10% CAGR 2011 - 2018 2,034 24.74 1,902 23.10 1,702 21.22 1,483 18.16 1,277 1,329 16.70 1,109 1,186 15.20 13.84 14.74 12.42 1,059 13.00 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 H1 2019 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 H1 2019 Dividend per share (p) Book Value per share (p) 14% CAGR 2011 - 2018 7% CAGR 2011 – H1 2019 143 146 16.42 14.35 15.35 126 13.40 11.25 116 7.65 9.30 6.40 106 4.93 100 92 94 86 4.60 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 H1 2019 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 H1 2019 3 1. Includes discontinued operations LEGAL & GENERAL GROUP PLC LEGAL & GENERAL GROUP PLC | HALF YEAR RESULTS | AUGUST 2019 We have 5 growing and profitable businesses Continuing Operating Profit from divisions (£m) CAGR H1 H1 Division Business 2016 2017 2018 % Growth opportunity % 2019 2018 832 651 716 Pension Risk • UK market: £25-30bn p.a. -

Paediatric Epilepsy Research Report 2019

Paediatric Epilepsy 2019 Research Report Inside Who we are The organisations and experts behind our research programme What we do Our strategy, projects and impact youngepilepsy.org.uk Contents Introduction 1 Who we are 2 Research Partners 2 Research Funding 4 Research Team 5 What we do 10 Programme Strategy 10 The MEG Project 12 New Research Projects 14 Research Project Update 21 Completed Projects 32 Awarded PhDs 36 Paediatric Epilepsy Masterclass 2018 37 Paediatric Epilepsy Research Retreat 2019 38 Research Publications 40 Unit Roles 47 Unit Roles in Education 49 Professional Recognition and Awards 50 Paediatric Epilepsy Research Report 2019 Introduction I am delighted to present our annual research report for the period July 2018 to June 2019 for the paediatric epilepsy research unit across Young Epilepsy, UCL GOS - Institute of Child Health and Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. We have initiated 13 new research projects, adding to 20 active projects spanning the clinical, educational and social elements of paediatric epilepsy. We have published 110 peer-reviewed items of primary research and a further 54 chapters in books, reviews and commentaries of expert opinion. During this period, Young Epilepsy Chief Executive Carol Long caught the research bug and moved on to begin her PhD at Durham University. We welcomed our new Chief Executive, Mark Devlin at our Paediatric Epilepsy Research Retreat in January 2019. As an organisation, we are launching a new strategy This report features a spotlight on a truly which sets our research programme as one of innovative project which will change the UK’s the four key offers at Young Epilepsy, and we diagnostic and surgical evaluation imaging suite look forward to sharing our research more widely for childhood epilepsy. -

Ian Gilmore Chair, UK Alcohol Health Alliance President, British Society of Gastroenterology Reflections on the ……

Ian Gilmore Chair, UK Alcohol Health Alliance President, British Society of Gastroenterology Reflections on the …… •challenges for hepatology •challenges for gastroenterology •challenges for the acute hospital •Challenges for the system •Challenges for society Challenges for hepatology Challenges for hepatology • Existing workforce (consultant, juniors, nurses • Recruitment into specialty • Relationship with gastroenterology • Relationship with G(I)M Challenges for gastroenterology Challenges for gastroenterology • Maintaining hepatology expertise • Relationships with ITU • 24/7 therapeutic endoscopy for bleeding • Repository for wider alcohol admissions? Quality and Productivity: Proven Case Study Alcohol Care Teams: reducing acute hospital admissions and improving quality of care Provided by: The British Society of Gastroenterology and Bolton NHS Foundation Trust Publication type: Quality and productivity example QIPP Evidence provides users with practical case studies that address the quality and productivity challenge in health and social care. All examples submitted are evaluated by NICE. This evaluation is based on the degree to which the initiative meets the QIPP criteria of savings, quality, evidence and implementability; each criterion is given a score which are then combined to give an overall score.r The overall score is used to identify the best examples, which ahn e then sow n or NHS Evidence as ‘eco mmended’. Our asseQIPPssment of the dforegree to walcoholhich this particular casecare study mee teamsts the criteria is represented in the evidence summary graphic below. Evidence summary Implementability Evidence of change Quality Savings 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Page 1 of 11 This document can be found online at: http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/qipp QIPP for alcohol care teams Challenges for the acute hospital Debate : is continuity now best delivered by a generalist ? Challenges for the system The new NHS – April 2013 Alcohol Related Admissions for Liverpool PCT (residents) 2002/03 to 2008/09 by Condition Group. -

Stardom: Industry of Desire 1

STARDOM What makes a star? Why do we have stars? Do we want or need them? Newspapers, magazines, TV chat shows, record sleeves—all display a proliferation of film star images. In the past, we have tended to see stars as cogs in a mass entertainment industry selling desires and ideologies. But since the 1970s, new approaches have explored the active role of the star in producing meanings, pleasures and identities for a diversity of audiences. Stardom brings together some of the best recent writing which represents these new approaches. Drawn from film history, sociology, textual analysis, audience research, psychoanalysis and cultural politics, the essays raise important questions for the politics of representation, the impact of stars on society and the cultural limitations and possibilities of stars. STARDOM Industry of Desire Edited by Christine Gledhill LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 1991 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge a division of Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc. 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1991 editorial matter, Christine Gledhill; individual articles © respective contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

More Wanderings in London E

1 MORE WANDERINGS IN LONDON E. V. LUCAS — — By E. V. LUCAS More Wanderings in London Cloud and Silver The Vermilion Box The Hausfrau Rampant Landmarks Listener's Lure Mr. Ingleside Over Bemerton's Loiterer's Harvest One Day and Another Fireside and Sunshine Character and Comedy Old Lamps for New The Hambledon Men The Open Road The Friendly Town Her Infinite Variety Good Company The Gentlest Art The Second Post A Little of Everything Harvest Home Variety Lane The Best of Lamb The Life of Charies Lamb A Swan and Her Friends A Wanderer in Venice A W^anderer in Paris A Wanderer in London A Wanderer in Holland A Wanderer in Florence Highways and Byways in Sussex Anne's Terrible Good Nature The Slowcoach and The Pocket Edition of the Works of Charies Lamb: i. Miscellaneous Prose; II. Elia; iii. Children's Books; iv. Poems and Plays; v. and vi. Letters. ST. MARTIN's-IN-THE-FIELDS, TRAFALGAR SQUARE MORE WANDERINGS IN LONDON BY E. V. LUCAS "You may depend upon it, all lives lived out of London are mistakes: more or less grievous—but mistakes" Sydney Smith WITH SIXTEEN DRAWINGS IN COLOUR BY H. M. LIVENS AND SEVENTEEN OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS NEW YORK GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY L'Jz Copyright, 1916, By George H. Doran Company NOV -7 1916 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ICI.A445536 PREFACE THIS book is a companion to A Wanderer in London^ published in 1906, and supplements it. New editions, bringing that work to date, will, I hope, continue to appear.